56

CHAPTER OUTLINE

■ ORGANIZATION OF GROUP THERAPIES

■ EMPIRICAL VALIDATION OF GROUP THERAPIES

■ GROUP THERAPIES FOR CO-OCCURRING DISORDERS

■ LIMITATIONS OF GROUP THERAPIES

Group therapies are used widely in the treatment of substance use disorders (SUDs) with and without co-occurring psychiatric disorders (CODs). These are often the main form of treatment in residential rehabilitation, psychiatric inpatient hospital, therapeutic community, halfway house, partial hospital, intensive outpatient, drug-free outpatient, and aftercare or continuing care programs. We use the term “group therapy” to refer to various types of groups described in this chapter including milieu groups, psycho-educational recovery groups, coping skills groups, therapy groups (also called problem-solving, interpersonal therapy, process, or counseling groups), and other groups (1,2).

Group therapies are often the preferred intervention of clinicians. For example, a survey of 67 Community Treatment Programs (CTPs) was conducted by the lead team (DD was a member of this team) of an outpatient study for the Clinical Trials Network (CTN) of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). The survey asked CTPs their preference of offering treatment in individual or group sessions for a twelve-step psychosocial intervention being tested in a multisite clinical trial for patients with cocaine or methamphetamine dependence. Survey results showed that the large majority of respondents preferred offering the intervention being studied in a group setting as they were more likely to adopt this intervention if it was provided in a group rather than an individual format (3).

Groups are used to address early recovery issues such as initiating abstinence and engaging the patient in a recovery process (4–9), anger management (10), relapse prevention (4,11–14), and co-occurring psychiatric disorders (15–20). Group therapies also are widely used in the treatment of specific clinical populations including women (21); alcoholics (22,23); persons in the criminal justice system (24,25); those dependent on marijuana (26), cocaine, or methamphetamine (3–5,27); and families of substance abusers (1,2,4,28–30).

This chapter provides an overview of group therapies. It reviews the goals and types of group therapies used to treat SUDs or CODs. It also provides a discussion on treatment outcome studies examining the effectiveness of group therapies for SUDs and their limitations. Training and supervision issues are discussed as well.

GOALS OF GROUP THERAPIES

The ultimate goal of addiction treatment is to enable an individual to achieve and maintain abstinence, but the immediate goals are to educate the individual about addiction, treatment, and recovery, help motivate them to stop or reduce drug or alcohol use, minimize the medical and psychosocial complications of addiction, and improve functioning and quality of life. Individuals in treatment for addiction often need to change their behaviors to adopt a healthier lifestyle. Group therapies help patients achieve these goals by creating a milieu in which members of a group can bond with each other, thus reducing the stigma associated with addiction and the humiliation of having lost control of one’s own behavior (1). The specific ways in which groups can help achieve this include providing education on addiction, recovery, and relapse; resolving ambivalence by overcoming denial and enhancing motivation to change; evoking hope and optimism for change; providing an opportunity to give and receive feedback from peers; teaching recovery skills to manage the addictive disorder over the long term; understanding and resolving problems contributing to or resulting from the addiction disorder, rather than avoiding such problems; providing a context in which the patient can identify with others and give and receive support; creating an experience of positive membership in a recovery-oriented group in which feelings, thoughts, and conflicts can be freely expressed; preparing the patient for involvement in long-term recovery; and facilitating the patient’s interest in participating in mutual support programs in addition to treatment groups (3,4). Treatment groups provide a context in which addicted persons can gain support, encouragement, feedback, and confrontation from peers who understand from personal experience how addicted individuals think, feel, and act, including the manipulations, schemes, and diversions they sometimes use to rationalize their substance use and other maladaptive behaviors (6).

ORGANIZATION OF GROUP THERAPIES

Group therapies vary in their theoretical underpinnings, structure, format, rules, number and duration of sessions, clinical focus, size, types of patients accepted, requirements for abstinence, approach to the group model, relative focus on content or process, and role of the group leader. Many types of recovery-oriented therapy groups are structured and content focused and depend on the leader to facilitate discussion of educational material with specific objectives and issues to cover in each session. These groups can accommodate larger numbers of patients than can therapy groups. Examples of group “models” include psychoeducational groups (3,4) motivational cognitive–behavioral groups (31), cognitive therapy groups (32), stages of change groups (33), or group programs such as NIDA’s recovery and self-help model (13) or the Matrix model of treatment that utilizes an extensive group component in addition to individual and family sessions (4,30).

Therapy or counseling groups usually are limited to 6 to 12 persons, with the content of discussions determined by the participants. Leaders are less verbally active in these groups and serve more as facilitators of members’ exploration of problems and sharing of support and feedback. Although some groups incorporate principles and information from mutual support programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), Narcotics Anonymous (NA), Cocaine Anonymous (CA), or Crystal Meth Anonymous (CMA), therapy groups differ from mutual support group meetings in their focus on systematic and/or in-depth exploration of psychological, interpersonal, social, spiritual, and intrapsychic issues. Structured inpatient, residential, partial hospital, and intensive outpatient treatment programs can last from several days to a year, thus exposing patients to considerable heterogeneity in the number and types of group sessions they receive. For example, a large multisite study of outpatient treatment for cocaine addiction (38) offered 39 individual sessions to patients in three of the four treatment conditions, in addition to 24 group counseling sessions, over a period of 6 months of active treatment and three additional monthly individual booster sessions, and one multifamily group. The Matrix model of treatment developed for cocaine and methamphetamine addiction offered 8 early recovery skills, 32 relapse prevention, and 36 social support group sessions (for 76 total group sessions) over 6+ months along with individual and family sessions (4,28).

Types of Group Therapies

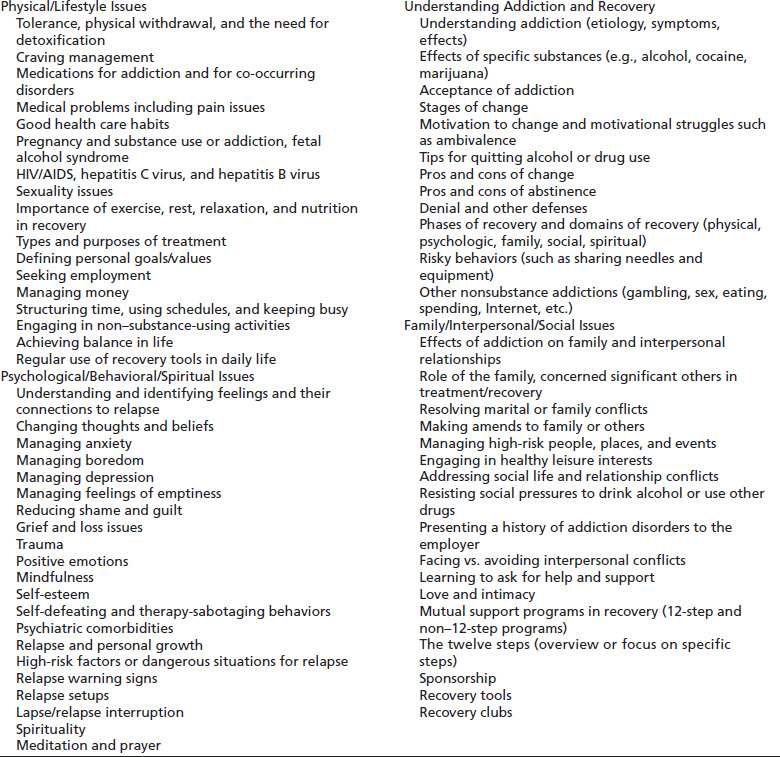

Although many different types and structures of group treatments are available for the treatment of SUDs, many of the problems or issues addressed are similar (Table 56-1). The number and specific issues or problems addressed in group depend on the treatment model and number of sessions offered. Group therapists or counselors employ a variety of techniques, such as providing education, eliciting support and feedback from members, confronting problematic behaviors, clarifying problems and feelings, helping the group remain focused, facilitating participant self-disclosure, teaching coping skills, and integrating experiential strategies relevant to the problems or issues being discussed. For example, the group leader may use behavioral rehearsals or role-plays to address interpersonal issues such as refusing offers to use substances or relationship conflicts, asking for an AA or NA sponsor, or dealing with a specific interpersonal conflict or problem. Or, the group leader may use an experiential technique such as a mono-drama to address internal conflicts such as low motivation or ambivalence to change or strong cravings for substances.

TABLE 56-1 ISSUES COMMONLY ADDRESSED IN RECOVERY GROUPS

Group therapies for substance use or co-occurring disorders usually fall into one of the following categories (1,2,4,15,16).

Milieu Groups

Milieu groups are offered in residential and hospital programs and usually involve a group meeting to start and/or end the day. A morning group may review the upcoming day’s schedule, discuss issues pertinent to the community of patients, ask each patient to state a goal for the day, or have patients listen to and reflect on the reading of the day (e.g., an inspirational reading from a recovery book such as 24 Hours a Day). An evening wrap-up group may review the day’s treatment and recovery activities and provide participants a chance to reflect on their experiences and insights gained from the day’s activities.

Psychoeducational Recovery Groups

These groups provide information about specific topics related to addiction and recovery and help patients begin to learn how to cope with the challenges of recovery (e.g., how to manage cravings to use alcohol or drugs, how to challenge thoughts of wanting to use substances or stop attendance at treatment, how to resist social pressure to use substances or how to reduce boredom that may precipitate relapse, and how to manage anger or other emotions in healthy ways; the impact of SUD on the family, medical, psychological, or spiritual aspects of addiction and recovery; and mutual support programs in recovery). These groups use a combination of lectures, discussions, educational videos, behavioral rehearsals, and completion of written assignments such as a recovery workbook or personal journal.

Coping Skill Groups

Skill groups are aimed at helping patients develop or improve their intrapersonal and interpersonal skills. For example, these groups teach problem-solving methods and stress management, cognitive, and relapse prevention (RP) strategies. RP groups help patients identify and manage early signs of relapse (the relapse “process”), identify and manage high-risk factors, or learn steps to take to intervene with a lapse or relapse.

Therapy or Counseling Groups (Also Called Problem-Solving or Process Groups)

These groups are less structured and give the participants an opportunity to create their own agenda in terms of problems, conflicts, or struggles to work on during group sessions. Any of the issues presented in Table 56-1 can be discussed based on the needs and problems of group members. These groups focus more on gaining insight and raising self-awareness than on education or skill development although participants can learn many things about addiction or recovery as well as be exposed to coping strategies that others have used to manage specific challenges of recovery from addiction such as the examples in the previous section on psychoeducational recovery groups.

Specialized Groups

These groups may be based on developmental stage (adolescents, young adults, adults, older adults), gender, different clinical populations (pregnant women or women with small children addicted to opioids, clients involved in the criminal justice system, clients with co-occurring psychiatric illness), or groups addressing specific issues or populations (parenting issues, anger or mood management, relapse prevention, or trauma).

More extensive discussions of various group approaches for addiction, such as interactional group therapy (34,35), modified dynamic group therapy (29,39), cognitive or cognitive–behavioral (12,31,32,43), psychoeducational and problem-solving (30), skills training (22), recovery stage-specific groups (6,9,33,37), or relapse prevention therapy (4,6,11) can be found in texts elsewhere.

Format of Group Sessions

Group sessions usually last from 60 to 90 minutes. Groups can be limited to a specific number of sessions in which all participants start the group together, or be open ended, so that new patients can be continuously added to the group programs in residential and intensive ambulatory programs often involve providing several groups during each treatment day, exposing patients to a variety of types of groups and clinical staff (although some programs use the same staff to conduct all groups provided during the day).

Treatment programs vary in the frequency of group sessions as well as whether individual and/or family sessions are also provided as part of a total “program.” For example, the Matrix model of addiction treatment, developed by Rawson et al. (4), offered individual and family sessions in addition to their extensive group program. In the Cocaine Collaborative multisite trial (38), 24 group sessions were provided to all study participants over 6 months. Three-fourths of patients randomized also received up to 42 individual sessions over 9 months in this study. In a recent study called STAGE-12 (Stimulant Groups to Engage in 12-Step Programs), participants received five weekly group sessions in addition to three individual sessions over an 8-week period while participating in a structured ambulatory intensive outpatient program (providing <15 hours per week of sessions) (3). The Washton (37) structured outpatient model involves group therapy two to four times each week in combination with weekly individual counseling sessions. He acknowledges that some patients are not able to tolerate group as a result of psychiatric and/or interpersonal impairment and need individual therapy. These examples show the diversity of treatment programs utilizing groups with clients who have SUDs.

Recovery Group Sessions

In the Collaborative Cocaine Study in which three of the authors participated, patients attended 90-minute Recovery Group sessions each week for 12 weeks (38,40,41). Each session focused on a specific topic relevant to early or middle recovery. At every session, patients were encouraged to abstain from all substances, seek and use a sponsor, participate in mutual support groups, and use the “tools” of recovery (e.g., talking about vs. acting on strong cravings, reaching out for support, and the like). Patients were encouraged to socialize with each other before the start of the session while the group leader administered a breathalyzer test. Each group session began with a check-in period (10 to 20 minutes), during which time patients briefly reported any substance use, strong cravings, or “close calls.” This was followed by a review of the topic for the session, lasting 40 to 60 minutes. Although the group leader had a specific curriculum for each meeting, the session was conducted in a way that encouraged patients to relate to the material in a personal way. Each session provided materials from a workbook that contained information about the topic and several questions for the patients to complete to relate the material to their own lives. During these discussions, patients were encouraged to ask questions, share personal experiences related to the psychoeducational material, give each other feedback, and identify strategies to manage their problems in recovery.

Each session ended with a brief review of patients’ plans for the coming week (10 to 15 minutes). Patients could discuss self-help meetings and other steps they could take toward recovery. Just before the session closed, patients recited the Serenity Prayer of AA. Topics of Phase 1 therapy sessions included the following (these topics are similar to those offered in other group approaches).

Session 1: Understanding Addiction

Addiction was defined as a biopsychosocial disorder in which multiple factors contributed to its development and maintenance. Symptoms of addiction were reviewed in terms of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (42), with a focus on compulsive use, impaired control, continued use despite negative consequences, tolerance changes, withdrawal syndrome, and psychosocial impairment.

Sessions 2 and 3: The Process of Recovery

Effects of addiction on all areas of functioning and the concept of denial were reviewed. Recovery was defined as a long-term process of abstinence and change involving multiple domains: physical, psychological, family, social, and spiritual. Each patient identified and discussed one area of change and a plan to achieve such change. Feedback was elicited from peers about the plan.

Sessions 4 and 5: Social and Interpersonal Issues in Recovery

The group discussed cravings, internal and external triggers, and enabling behaviors on the part of other people in the patient’s life. Major emphasis was given to identifying and learning to manage direct and indirect social pressures to engage in substance use (people, places, events, and things). The effects of addiction on family and relationships and activities were described, and patients discussed strategies to address interpersonal problems in early recovery. Finally, components of healthy relationships were discussed.

Sessions 6 and 7: Mutual Support Programs and Support Systems

The importance of participating in twelve-step programs of AA, NA, and CA was emphasized in all group sessions; these two sessions provided specific information on types of meetings, sponsorship, the twelve steps, and other tools of recovery. Barriers and negative perceptions or experiences with self-help programs were discussed, as were the benefits of self-help programs. Discussions also addressed sources of support outside AA, NA, CMA, and CA (e.g., family, friends, recovery clubs, and organizations); barriers to asking for help; and ways to actually ask others for help.

Sessions 8 and 9: Managing Feelings in Recovery

These sessions focused on understanding the connection between feelings and substance use and becoming aware of “high-risk” emotional states associated with relapse. Strategies to manage feelings were reviewed, and patients were asked to develop a plan to address one emotional state they felt was a problem for them (such as anger, anxiety, boredom, depression, or loneliness). An entire session focused on understanding and dealing with guilt and shame, as these feelings are so common among patients in early recovery.

Sessions 10, 11, and 12: Relapse Prevention and Maintenance

Relapse was defined as both a process and an event, with both obvious and covert warning signs. These sessions focused on helping patients identify and manage warnings of relapse, as well as individual high-risk situations. Common risk factors identified in research studies were reviewed to help patients learn to anticipate and prepare to address them. Strategies for maintaining recovery over time and using the tools of recovery on a daily basis also were discussed.

Phase 2: Problem-Solving (Therapy) Groups

Phase 2 groups met for 90 minutes weekly for 12 sessions after completing Phase 1. The goals were to help patients identify, rank, and discuss their problems in recovery and identify strategies to manage these problems to reduce relapse risk. Sessions provided an opportunity for patients to give and receive support and feedback from peers. After the check-in period—in which patients reported on any episodes of use, strong cravings, or close calls—they were asked to identify a problem or recovery issue for discussion in the group. Often, more than one member would identify a similar problem or issue for discussion. The issues and problems reviewed in the psychoeducational groups were revisited frequently. Issues discussed often involved struggles with motivation to change or remain abstinent; persistent obsessions; compulsions and close calls to use cocaine or other substances; actual lapses or relapses; boredom with sobriety; upsetting emotional states (e.g., anxiety, anger, depression); concerns or experiences with self-help programs; the twelve steps or a sponsor; interpersonal problems and pressures to use substances; financial, job, and lifestyle problems; other addictions; and spirituality. At the end of each session, patients were asked to state their plans for the coming week in terms of attendance at self-help meetings or other steps they could take to aid their recovery or resolve a problem.

Group Process Issues

In both Phases 1 and 2, group counselors had to attend to the group process to keep the group focused and productive. This attention required counselors to engage quiet members in discussions and facilitate their self-disclosure and to limit or redirect members who talked too much and tried to dominate group discussions, listened poorly to fellow group members, or tried to use the group to obtain individual therapy from the leader. Counselors kept the group from going off on unrelated tangents or talking in generalities, balanced the discussions between problems and coping strategies, facilitated group members’ sharing of support and feedback, and addressed impasses or problems in the group. In Phase 1 groups, the counselor had to ensure that the curriculum for each session was covered, because this was viewed as an important part of treatment.

Obstacles to Group Therapy

Researchers who have written about group treatments identify problems with group participants that create obstacles to treatment. Washton (6) reports the following problems among members of therapy groups: lateness and absenteeism, intoxication, hostility and chronic complaining, silence and lack of participation, terse and superficial presentations, factual reporting and focusing on externals, proselytizing and hiding behind AA, and playing cotherapist. In his classic text on group psychotherapy, Yalom (34) identified a number of “recurring behavioral constellations” that occur in the treatment group. He identified these constellations as monopolist, schizoid, silent, boring, help-rejecting complainer, self-righteous moralist, psychotic, narcissistic, and borderline. Because the problems affect the group as a whole, the leader must have strategies to address any that arise in the course of a group session. For example, if a member consistently rejects the advice or feedback of other group members, the group leader can point out this pattern and engage the group in a discussion of why this pattern is occurring. The members who offer help and support only to have their attempts rejected can be asked to talk about what this feels like so that the member who rejects their help is aware of the impact this behavior has on others.

Family Psychoeducational Groups (Sometimes Called Family Workshops or FPWs)

These FPWs and other family programs are used to educate the family, provide support, help reduce the family’s burden, increase helpful behaviors, and decrease unhelpful behaviors (4,28–30

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree