Community Story

Common River is a U.S.-based nongovernmental organization (NGO) implementing a community development program in Aleta Wondo, Ethiopia. This NGO is founded on the principle of positive deviance, in which local best practices are identified and replicated to maximize agricultural production (organically grown coffee is produced in this region), as well as to improve the nutritional status, health, and education of orphaned and vulnerable children. Since 2009, a group from the University of Texas School of Medicine has travelled annually to Aleta Wondo to provide school health screening and free healthcare, including treatment of endemic helminth infections, trachoma, and skin diseases, while collaborating with and supporting the local government-sponsored health clinic (Figures 7-1A and B). In Figure 7-1C, the schoolchildren of Common River are looking at the new group of American medical students that have just arrived in Africa. In the coming week, these children will receive oral albendazole to treat intestinal parasites and have complete physical exams to detect and treat other common conditions, such as head lice, tinea capitis, trachoma, and foot infections. Note that many of the children are barefoot. In Figure 7-1D, a group of women has just completed their woman’s literacy class for the day. Improving women’s literacy can improve the health of the entire community.

Figure 7-1

A. Many people still live in extreme poverty with no running water and electricity. This is a typical hut in Ethiopia. This one is inhabited by a grandmother, her grandchild and a cow. The photograph was taken after a home visit to provide IM ceftriaxone to the child after her release from the local hospital where she was treated for a neck abscess and cellulitis. The medical team was staying at Common River and originated from the University of Texas. (Courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD.) B. A University of Texas medical student helps an elderly man to a chair where he will be seen by the medical team working in Aleta Wondo. One of the local nursing students is observing the clinical activity. (Courtesy of Lester Rosebrock.) C. The schoolchildren of Common River in rural Ethiopia greet the new group of American medical students that have just arrived in Africa. D. Smiling women that have just completed their woman’s literacy class for the day. Improving woman’s literacy is a great way to raise the health status of the community. (Courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

What Is Global Health?

For years, the term international health has described health work in resource-limited settings with an emphasis on tropical diseases, communicable diseases, and illness caused by poor nutrition and inadequate access to water, sanitation, and maternal care.1 More recently, global health is commonly used to emphasize mutual sharing of experience and knowledge, in a bilateral exchange between industrialized nations and resource-limited countries, and the emphasis is expanding to include noncommunicable diseases and chronic illness.2 One definition of global health, proposed by the Consortium of Universities for Global Health Executive Board, is “an area for study, research, and practice that places a priority on improving health and achieving equity in health for all people worldwide.”1 This chapter focuses on a few conditions commonly encountered in developing nations, emphasizing communicable diseases and malnutrition.

Ethical dilemmas abound when professionals from resource-rich settings leave their familiar environment and apply their practices in a severely resource limited setting. Consider, for example, breastfeeding guidelines in the setting of maternal-to-child HIV prevention. National protocols differ depending on resource availability. In some settings, telling an HIV-positive mother not to breastfeed (because breast-milk can transmit HIV) may sentence her infant to near-certain death from diarrhea. If a program overturns local teaching about exclusive breastfeeding, it must ensure a safe and sustainable alternative form of infant feeding. Imposing the standards of industrialized nations in a community that cannot afford to continue to provide these standards can undo years of program development. Care must be taken not to undermine the trust a community has placed in local health providers, as this can ultimately increase morbidity rather than relieve suffering. Working with local health providers is essential so that a short trip can result in extended benefits to the community (Figure 7-2).

Figure 7-2

The physician in the front of this picture is pleased to receive medications that are unavailable to her hospital in rural Panama. Before shipping or bringing medications abroad, it is essential to learn what practicing physicians need. Bringing redundant or nearly expired meds or short-term supplies of expensive brand medications causes more harm than good. Donated medications should be locally relevant generics that are not expired. The WHO list of essential medications may be helpful in planning (). (Courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

This chapter briefly introduces some of the relevant subject areas with which global health providers should familiarize themselves when preparing for international work. Statistics that aid in understanding the state of a nation’s health relative to other countries are the mortality rate of children younger than age of 5 years old and adult life expectancy. Least-developed countries report that as many as 112 of 1000 children die before age 5 years, compared to 8 per 1000 in developed countries,3 and adult life expectancy ranges from 48 or 49 years at birth (Chad, Swaziland) to 88 or 89 years (Japan, Monaco).3 Another important parameter by which to compare the health status of countries is that of maternal mortality, defined as the number of maternal deaths per 100,000 livebirths. These figures, together with basic epidemiology of disease provide important insights into public health priorities for populations.

What statistics do not provide, however, is the level of importance ascribed to a particular health issue by a community. It is necessary to acknowledge and address the needs expressed by communities themselves, in order of their own priorities, so as to achieve sustained improvements in health outcomes. All health improvements ultimately rely on long-term behavioral changes, whether dietary, pill taking, physical activity, or hygiene related. Group behavioral change requires buy-in from the population with approbation and influence of local leadership.

A useful method of creating a positive impact is to make use of ongoing peer-to-peer adult education techniques through the introduction of community health clubs. This can be effective for empowering resource-limited communities to develop their priorities, and to advocate for their community health and development needs.4 It is best to learn about and collaborate with the local and governmental community health activities before launching any intervention, be it clinical, infrastructural, or preventive.

Many diseases in resource-poor settings are traceable to deficits in clean water supply and storage, lack of soap for bathing, and lack of functioning infrastructure to manage human waste (garbage collection, latrines) (Figure 7-3). Some of the most important ones include typhoid fever, cholera, and intestinal parasites.

Figure 7-3

A. A covered pit latrine serving the needs of an Ethiopian family. The latrine is located on the edge of the garden near their home, and presents a fall hazard for young children. (Courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD.) B. An Ethiopian pit latrine, which offers no mitigation for flies and is situated in proximity to the water table below. Heavy rains will lead to contamination of the water supply with fecal pathogens. (Courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD.) C. An elevated, ventilated improved pit latrine can protect the water table and reduce flies. Air circulates down the squat hole, into the pit and up through the pipe. To ensure unhindered flow of air, the top of the vent pipe must be 0.5 meters above the top of the shelter. The latrine interior is kept dark so the main light source in the pit comes from the vent pipe. Flies are attracted to the light, but the pipe has a fly-proof screen at the top, so they cannot escape and eventually die.5 Many countries consider the ventilated improved pit latrine to be the minimum standard for improved sanitation. (Courtesy of Jason Rosenfeld, MPH.)

Lack of governmental and public health infrastructure in the developing world leads to large populations living without clean running water. World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF estimate that 780 million persons are without access to improved water sources and 2.5 billion (37% of the world’s population) people are without access to improved sanitation sources.6

Water and sanitation deficiencies are responsible for most of the global burden of diarrheal disease. The most common diarrheal disease of returning travelers is caused by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. All over the world, young and malnourished children die of preventable diarrhea caused by rotavirus, E. coli, Salmonella, Shigella, and Campylobacter.

Diseases that are particularly deadly as a result of lack of access to clean water include typhoid fever and cholera. Intestinal parasites, while usually not deadly, do lead to chronic problems with malnutrition and anemia, which themselves contribute to cyclical poverty and disease because they lead to impaired learning, reduced productivity, and vulnerability to other infectious diseases.

Typhoid Fever

Typhoid fever, also known as enteric fever, is an acute systemic illness caused by the invasive bacterial pathogen, Salmonella typhi. Salmonella is ingested in contaminated water or food, invades the mucosal surface of the small intestine, and causes bacteremia, with seeding of the liver, spleen and lymph nodes.

Typhoid fever is mainly found in countries with poor sanitary conditions. Because most such countries do not routinely confirm the diagnosis with blood cultures, the disease is highly underreported. Outbreaks of typhoid are often seen in the rainy season, and in areas where human fecal material washes into sources of drinking water. Shallow water tables and improperly placed latrines are environmental risk factors for typhoid. Globally there are 16 to 33 million cases annually, with up to a half a million deaths every year.7

Patients develop an acute systemic illness with prolonged fever, malaise, and abdominal pain after ingesting contaminated food or water. This truly nonspecific syndrome may include headache, mild cough, and constipation, with nausea and vomiting. Diarrhea may be present but it is not the rule. After a 10- to 20-day incubation period, there is a stepwise progression of fever over a period of 3 weeks, and the patient may display a transient rash described as rose spots (2- to 4-mm pink macules on the torso, which fade on pressure). Temperature pulse dissociation with relative bradycardia despite high fever may be noted in fewer than 25% of patients. In the second week, the patient becomes more toxic and may develop hepatosplenomegaly. Untreated, typhoid can progress to include delirium, neurologic complications and intestinal perforation caused by a proliferation of Salmonella in the Peyer patches (lymphoid tissue) of the intestinal mucosa. Although the mortality rate for untreated typhoid is 20%, early antibiotic therapy can decrease mortality. Approximately 1% to 4% of those who recover from acute typhoid fever become carriers of the disease who continue to shed Salmonella in their stool despite not being ill.7

- Malaria (often clinically indistinguishable from typhoid; empiric therapy for both malaria and typhoid may be warranted if diagnostic testing is unavailable).

- Enteroinvasive E. coli

- Campylobacter

- Paratyphoid fever (Salmonella para typhi, other less virulent Salmonellae)

- Dengue fever (mosquito borne arbovirus infection spread by Aedes aegypti)

- Rickettsial diseases (typhus, spotted fever, Q fever)

- Brucellosis

- Leptospirosis

- Heat stroke

Prompt diagnosis and initiation of antibiotic therapy is essential and life-saving. Oral rehydration therapy should be initiated first, followed by IV fluids if vomiting cannot be controlled and for patients with altered mental status or hypovolemic shock. Antibiotic resistance patterns differ with geographic location.

For Africa and resource-limited settings in the Americas, the first choice is chloramphenicol 1 g PO daily for 10 to 14 days, or ciprofloxacin. Historically, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 960 mg PO twice daily for 10 to 14 days has been used,8 but there has been increasing drug resistance to sulfa in these areas. In Asia, where multidrug resistant S. typhi strains are well described, ciprofloxacin (500 to 750 mg twice daily), ceftriaxone (60 mg/kg IV daily) or azithromycin (500 mg daily) may be used for 7 to 14 days.8–10 Azithromycin should only be used in mild disease. Some guidelines advocate the use of dexamethasone, 3 mg/kg IV followed by 1 mg/kg every 6 hours for 2 days in the setting of shock or altered mental status.8 See vaccine information at the end of this chapter.

Cholera

Cholera is an acute, diarrheal disease caused by Vibrio cholerae. It is usually transmitted by contaminated water or food, and is associated with pandemics in countries that lack public health infrastructure and resources for sanitation. Although the infection is often mild or asymptomatic, in 5% to 10% of patients it can be severe and life-threatening.14

V. cholerae reservoirs occur in brackish and salt water, as well as estuaries. Although the organism occurs in association with copepods and zooplankton, its largest reservoir is in humans. Cholera pandemics have been reported in south Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Characteristically, cholera outbreaks occur in countries that have suffered destruction of public health infrastructure (collapse of water supplies, sanitation, and garbage collection systems). The 2010 outbreak in postearthquake Haiti has been traced to UN Peace-keeping soldiers, whose waste contaminated a major Haitian river used for bathing, irrigation, and drinking water. In just 10 months, 300,000 cases were reported, of whom 4500 died, and the outbreak has continued to wax and wane with the rainy seasons for years.11 A large infective dose is necessary for infection, and although only approximately 10% of those infected fall ill, the infection can be fatal for young children, elderly, and malnourished individuals.

V. cholerae is a motile, gram-negative rod. After ingestion via contaminated water or food, it must survive the acid environment of the stomach before colonizing the mucosal surface of the small intestine. The organism is noninvasive, and not associated with bloody diarrhea. Rather, it makes a potent toxin causing massive secretion of electrolyte-rich fluid into the gut lumen. Human to human contact spread virtually never occurs. Transmission through contaminated food or water is the rule.12

Clinical presentation ranges from mild watery diarrhea to acute, fulminant watery diarrhea which looks like rice water. After an incubation period of 18 to 40 hours, patients may lose up to 30 L of fluid daily, with resulting metabolic acidosis and electrolyte disturbances. Severe dehydration can lead to death in a matter of hours. Vomiting, when present, starts after the onset of diarrhea. Profoundly dehydrated patients present with decreased skin turgor, sunken eyes, and lethargy. Children, but not adults, may have mild fever. Cramping caused by loss of calcium and potassium is common.12

Early presentation may resemble enterotoxigenic E. coli; however, the syndrome is quickly distinguishable because of the extreme volume of “rice water” secretory diarrhea that is the result of cholera toxin. V. cholerae may be confirmed by stool culture, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for toxin genes, or dark-field microscopy with specific antisera, which will immobilize the V. cholerae.13 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends confirmation of cholera by stool specimen culture or rectal swab. For transport, Cary Blair media is used, and for identification, thiosulfate-citrate-bile-salts (TCBS) agar is recommended.14

Water, sanitation, and hygiene education is essential, as is education about recognizing the symptoms and immediately seeking medical attention while initiating oral rehydration. Optimally, rehydration should commence with reconstitution of WHO-distributed oral rehydration salts (ORS), which is available in all but the most remote areas of the world. Hydration is the mainstay of therapy, and replacement of fluids should be calibrated to match losses. ORS should be prepared with previously boiled water and consumed within 24 hours of reconstitution. IV or intraosseous hydration with Ringer lactate solution should be initiated if the patient is vomiting or in danger of hypovolemic shock. The volume needed to rehydrate a cholera patient is often underestimated; for this reason, collection and measurement of the watery stool in a bucket placed under the cholera cot is recommended.

Antibiotics are recommended for severe cases of cholera; options include15:

Doxycycline 300 mg orally as single dose (contraindicated in pregnancy)

Azithromycin 1 g orally as single dose (more effective than either erythromycin or ciprofloxacin; appropriate first-line therapy for children and in pregnancy)

Ciprofloxacin

Furazolidone 100 mg orally

In pregnancy, erythromycin 250 mg PO daily for 3 days may also be used.

Drinking purified or treated water, good handwashing practices, and avoidance of contaminated food are essential. Travellers should be reminded not to brush their teeth with tap water and to avoid having potentially contaminated ice added to their beverages. Carbonated beverages are safe as the carbonation process is bactericidal. Community education about handwashing and treatment of water is essential. In communities lacking running water (Figure 7-4), home storage of drinking water should be in containers with protective lids. Local guidelines regarding addition of chlorine to home stored water containers should be followed.

Figure 7-4

In this Ethiopian community without running water, water is collected in Jerry cans. Thousands of women carry these heavy, filled cans for miles after filling them up from this single pipe. The local town has provided one single pipe as the water source for the community. Although there is muddy water below, the water coming from the pipe appears clear, although it is likely to harbor bacteria and parasites. (Courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

Intestinal Parasites

One-third of the world’s population is infected with intestinal parasites, and although many parasitic infections are asymptomatic, some have serious health consequences. Especially affected are pregnant women and children, for whom hookworm-associated anemia results in maternal mortality, low-birth-weight babies, growth stunting, and impaired learning. The CDC recommends predeparture albendazole treatment as a single 600-mg dose for all refugees from sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. While this treatment will eradicate most of the nematodes, it is insufficient for Strongyloides stercoralis and schistosomiasis.16

Abdominal pain, cramps, bloating, anorexia, anemia, fatigue, growth stunting of children, hepatomegaly (schistosomiasis).

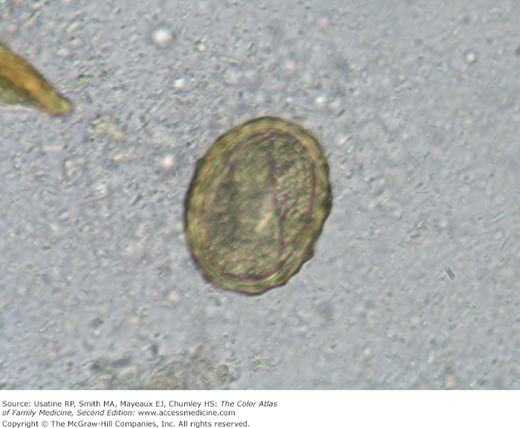

Stool for ova and parasite studies (Figure 7-5). Note that these will not reliably detect Strongyloides or schistosomiasis; serologic testing is available for the latter. Eosinophilia is an important diagnostic clue for the presence of parasites; the finding of persistent eosinophilia warrants a careful diagnostic evaluation for parasitic infection.

Albendazole 400 mg orally as single dose will eradicate hookworm, and Ascaris, but not Trichuris in most people.17 Eradication of Trichuris trichiura requires 3 daily doses of albendazole or adding ivermectin to mebendazole.18

Albendazole 200 mg orally as a single dose.19 S. stercoralis requires 7 days of albendazole at 400 mg twice daily. For schistosomiasis, praziquantel is effective against all species of schistosomes. Give 2 doses of 20 mg/kg PO 4 to 6 hours apart (3 doses 4 hours apart for Schistosoma japonicum).20

Preventative measures include proper management of human waste, handwashing after defecation and before cooking, and wearing shoes (prevents hookworm and Strongyloides). WHO guidelines recommend mass treatment of school children in endemic areas with single-dose albendazole therapy once every 6 months.

Malnutrition

A global shift is underway, from diseases of undernutrition to overnutrition in tandem with industrialization and advances in transportation and technology. In spite of this global shift, about a quarter of the world’s preschool children demonstrate growth stunting caused by nutritional deficiencies. In resource-poor countries, adult obesity and childhood undernutrition may coexist within the same families. The causes of this seeming paradox include many factors associated with poverty: the vulnerability of preschool children to infection when sanitation is inadequate, lack of nutrition education, decreased physical activity with increasing availability of technology and transportation, and mass marketing of inexpensive, calorie-rich foods.

Two classic presentations of malnutrition in children are important to recognize because they signal a patient who is immunocompromised and vulnerable not only to infection but also to preventable developmental delay. The accompanying photographs show an emaciated child with marasmus (severe, nonedematous malnutrition caused by calorie deprivation; Figure 7-6), and a puffy child with kwashiorkor (severe, edematous protein energy malnutrition; Figure 7-7). Marasmic kwashiorkor is another descriptor, illustrating the high level of overlap in the etiology and presentation of these extreme forms of malnutrition.21 Whenever possible, one should avoid hospitalizing these children for nutritional rehabilitation as hospitalization will expose them to many infectious pathogens that could be lethal during their vulnerable period of “nutritional AIDS.”22

Figure 7-7

This 2-year-old child presented with classic signs and symptoms of kwashiorkor, a severe form of protein-energy malnutrition. The word kwashiorkor, from a Ghanaian language, refers to the sickness a child develops when it is weaned from breastfeeding. In countries with limited protein sources, newly weaned children are especially vulnerable to this disease. They present with depigmentation, red discoloration of the hair, distended abdomens, and peripheral edema. (Courtesy of Ruth Berggren, MD.)

Growth chart monitoring is important for earliest detection of weight loss, growth stunting, or failure to gain height and weight over time. In most resource-poor countries, growth monitoring is implemented by trained community health workers, who refer mothers for nutrition and education programs upon detecting faltering growth in children younger than the age of 5 years. Children often fail to gain weight normally after an episode of infectious diarrhea or malaria; this should be followed by a period of rapid catchup growth. If a child becomes reinfected before catchup growth is complete, the child will fall further behind on the growth curve.

Depending on the relative protein content of the diet, patients develop marasmus (calorie deprivation), characterized by emaciation and listlessness (Figure 7-6), or kwashiorkor, “the disease of weaning”—protein-energy malnutrition. Kwashiorkor is characterized by red discoloration of the hair (Figure 7-8), which is also brittle, puffy eyes, bloated bellies and pitting edema of the extremities (Figure 7-7). These children feel miserable and are lethargic and uninterested in food. The differential diagnosis of kwashiorkor includes nephrotic syndrome, renal failure, or right-side congestive heart failure.

Childhood malnutrition, and especially kwashiorkor, may begin when a breastfeeding mother weans her child from the breast. Deprived of protective maternal antibodies and protein source, weaning infants begin sampling their contaminated environments and ingesting pathogens. Production of cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α during infectious episodes suppresses appetite and impedes nutritional recovery.22

Micronutrient deficiencies coexist,21 and deficiencies of vitamin A and zinc, in particular, predispose children to increased morbidity from subsequent infections. When parents are unable to replace protein requirements of weaning infants, children eat whatever locally available calorie sources (grains, cereals, bread, fruit) they can find. The poor in many developing countries lack protein sources and toddlers are frequently not prioritized when meat, milk, or eggs become available.

As a result of severe protein deficiency, hypoalbuminemia and decreased intravascular oncotic pressure lead to edema, and the classic puffy appearance of the child with kwashiorkor. For years it was believed that children with kwashiorkor are disproportionately deprived of protein, whereas children with marasmus are deprived of both protein and carbohydrate calories proportionally; it now appears there is a great deal of overlap between these two presentations of severe malnutrition.21

The endless cycle of infection leading to poor appetite and weight loss leading to malnutrition and further risk of infection22 can be difficult to break unless mothers of malnourished children are taught to introduce calorie-dense weaning food supplements and snacks. Many countries have locally produced ready-to-use therapeutic foods (RUTF),21 offering products like Plumpy’nut, or Haiti’s Nourimanba, made from peanut butter, milk powder, vegetable oil, sugar, and a vitamin mix.23

These therapeutic foods are a useful adjunct to breaking the cycle of infection, anorexia, weight loss and malnutrition, but they are not a substitute for educating mothers about how to rehabilitate their malnourished child using locally available and affordable foods. Nonmeat protein substitutes, such as red beans, and locally available green leafy vegetables are easier for mothers to obtain than meat, cow’s milk, or expensive imported food supplements.

Micronutrient Deficiencies

In contrast to marasmus and kwashiorkor, growth stunting is a more subtle syndrome affecting 200 million children who are younger than the age of 5 years. A variety of micronutrient deficiencies are believed to contribute to stunting syndrome and to accompany developmental delays, reduced cognitive function, impaired immunity, and future risk of obesity and hypertension.24 There are 4 micronutrient deficiencies of global importance, each with associated clinical syndromes that should be recognized. All can be associated with growth stunting in children, who may present with abnormally short stature but relatively normal weight for height.

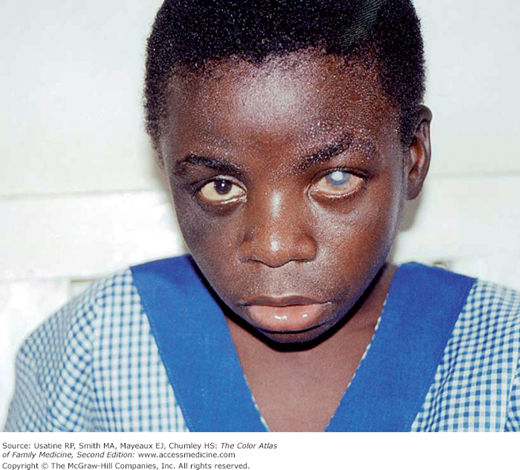

Vitamin A is a critical regulator of immune function, which is required for maintaining the integrity of mucosal surfaces. Vitamin A supplementation in countries with malnutrition reduces blindness (from xerophthalmia) as well as the morbidity of infectious diseases (especially measles, diarrhea, and respiratory infections). Figure 7-9 shows a photograph of blindness caused by vitamin A deficiency. In 2009, the WHO estimated that clinical vitamin A deficiency (night blindness) and biochemical vitamin A deficiency (serum retinol concentration <0.70 μmol/L) affected 5.2 and 190 million preschool-age children, respectively.26 About 250,000 children develop blindness caused by vitamin A deficiency every year, and half of these die within 12 months of losing sight.27

Figure 7-9

Child with severe xerophthalmia of the left eye secondary to vitamin A deficiency.25 (Used with permission from SIGHT AND LIFE www.sightandlife.org.)

The earliest presentation of vitamin A deficiency is poor night vision, which may progress to night blindness, xerophthalmia, ulceration, and scarring of the cornea, with ultimate blindness. Vitamin A deficiency is also associated with anemia, and is particularly dangerous in patients with measles, for whom mortality rates are high.

A metaanalysis of 43 trials involving 216,000 children younger than the age of 5 years who were given vitamin A supplements revealed striking reductions in mortality and morbidity. Seventeen of these trials reported a 24% reduction in mortality, and 7 trials reported a 28% reduction in mortality associated with diarrhea. Vitamin A reduced diarrhea and measles incidence. Vitamin A significantly reduces morbidity, mortality, and eye disease. Vitamin A supplements are recommended to all children who are at risk in low- and middle-income countries.28

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree