GIANT CELL-RICH TUMORS

10.1 Plexiform Fibrohistiocytic Tumor

10.2 Tenosynovial Giant Cell Tumors

10.3 Giant Cell Tumor of Soft Tissue

10.1 Plexiform Fibrohistiocytic Tumor

Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor (PFHT) is a very unusual, distinctive soft tissue tumor of the superficial soft tissues with a predilection for children, adolescents, and young adults. The majority of PFHT occur in the upper extremity, commonly in the more distal aspect (hand or wrist region). About one-third of PFHTs are located in the lower extremity, and rare examples have been noted in the head and neck regions. PFHTs present as mass or plaque-like lesions at the interface of the dermis and subcutaneous soft tissues.

PFHTs are often infiltrative and difficult to excise completely. As such, there is a strong proclivity for local recurrence. PFHT is considered an intermediategrade lesion because of a potential for recurrence and in very rare cases, metastases to the lungs or lymph nodes. Complete surgical excision is considered the best treatment option. To date, no signature molecular or cytogenetic abnormalities have been ascribed to PFHT.

HISTOPATHOLOGY

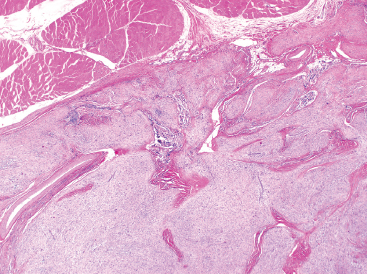

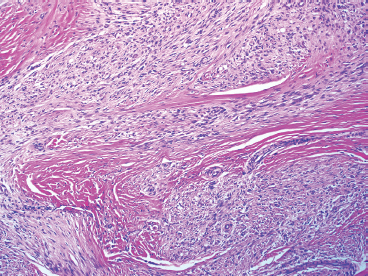

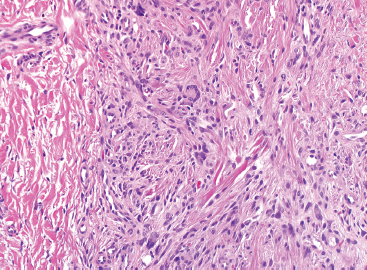

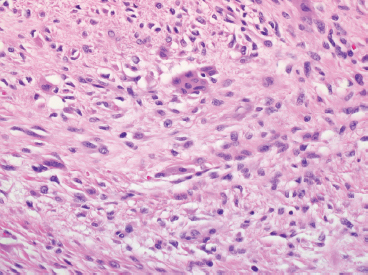

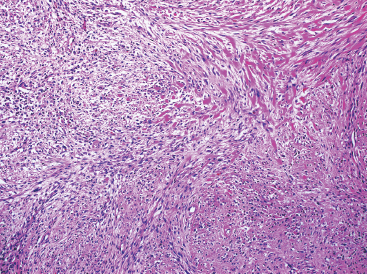

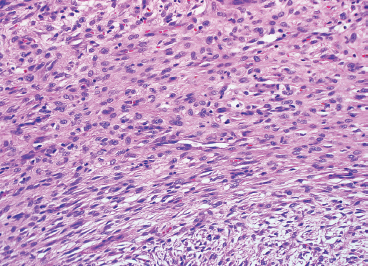

As the name implies, PFHTs are often plexiform or multinodular in configuration (Figure 10.1.1). As mentioned before, PFHT is a superficially based, subcutaneous lesion, often small (3 cm or less) at the time of detection. The nodules of PFHT are round or sometimes elongated, ovoid shaped, and separated by fibrous strands, similar to the pattern identified in association with plexiform neurofibroma (Figure 10.1.2). Three distinctive types of cells are identified in PFHT: mononuclear histiocytoid cells, spindled myofibroblastic cells, and multinucleate, osteoclast-type giant cells (Figures 10.1.3 and 10.1.4). Individual nodules are composed of varying mixtures of these cellular components. Histologic subtyping of PFHT has been proposed based on the predominance of one feature over the other. In the mononuclear subtype, there is a predominance of histiocytoid and multinucleated cells. The fibroblastic subtype of PFHT is comprised of prominent fascicles of the spindled cells, giving this variant a histologic resemblance to fibromatosis (Figure 10.1.5). In this latter variant, the plexiform or multinodular arrangement of tumor may be less distinctive than in the more classic descriptions of PFHT, and the mononuclear component may be represented as small foci located between long fascicles of spindled cells. In addition to these different histologic variants of PFHT, there is a proposed “mixed” type, where all features are well represented. The issue of “subtype” is useful for histologic and diagnostic recognition only. There is no prognostic significance attached to any particular variant of PFHT.

In any given subtype, the juxtaposition of the spindled cells with the mononuclear component often gives PFHT something of a biphasic appearance on low-power microscopic examination. A higherpower examination of the histiocytoid component will reveal a relatively uniform population of epithelioid-appearing cells with indistinct pale cytoplasm (Figure 10.1.6). The nuclei are usually monomorphic in appearance with fine chromatin and small nucleoli. Scattered throughout the mononuclear population are small osteoclast-type giant cells. These can be relatively inconspicuous and can often be missed on a cursory histologic examination of PFHT. The spindled cell component of PFHT may surround and isolate nodules of mononuclear cells or appear as a more “desmoid”-like pattern of interconnecting bands. The cells of the spindled component contain small bland nuclei. Necrosis and mitotic activity are not prominent features of PFHT. Of note, “invasion” into small vessels can be demonstrated in some cases of PFHT. In addition, larger lesions will often focally infiltrate adjacent skeletal muscle.

Immunohistochemistry can be of value in helping to distinguish PFHT from some histologic mimics, particularly the superficial fibromatosis. Staining for histiocytic markers such as CD68 or CD163 can be useful in highlighting small nodules of mononuclear cells and giant cells. Histiocytes and giant cells should be absent in a true fibromatosis. However, PFHT typically lacks immunoreactivity to betacatenin, a maker of fibromatosis. The spindled cell component of PFHT will stain for smooth muscle actin, a feature not particularly useful for separating this lesion from other fibrous or fibrohistiocytic proliferations. PFHT can often show histologic overlap with cellular neurothekeoma. In this instance, microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) can be helpful in differentiating the two.

CYTOLOGIC FINDINGS

Isolated reports of the cytologic findings of PFHT have been reported in the literature. They are described as being very cellular aspirates composed of plump histiocytoid spindled cells with rare multinucleate giant cells. In one particularly well-illustrated example, nuclear pseudoinclusions were identified. Because of the overall cellularity of this lesion, PFHT can potentially be confused with other spindle cell lesions including dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, (spindled) malignant melanoma, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor.

FIGURE 10.1.1 On low power, plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor (PFHT) has a very plexiform, multinodular architecture. The contrast between the cellular component and the fibrous tissue gives this lesion a biphasic appearance.

FIGURE 10.1.2 The plexiform arrangement can mimic the appearance of a plexiform type of neurofibroma.

FIGURE 10.1.3 Within PFHT are small osteoclast-like giant cells.

FIGURE 10.1.4 The giant cells of PFHT are often poorly formed and may be sparse.

FIGURE 10.1.5 PFHT often has a fascicular pattern that is reminiscent of fibromatosis.

FIGURE 10.1.6 Close inspection of the mononuclear population reveals a uniform population of small epithelioid cells with indistinct cytoplasmic borders.

10.2 Tenosynovial Giant Cell Tumors

Giant cell tumors of soft tissue/tendon sheath, also commonly referred to as tenosynovial giant cell tumors, can be divided into two distinctive subtypes: localized and diffuse. The two subtypes have significant differences in clinical presentations and prognoses. The localized type is often referred to as giant cell tumor of tendon sheath (GCTTS) and is fairly common. GCTTS occurs preferentially on the distal extremities, with fingers, hands, and feet being the most common locations (Figure 10.2.1). Rare GCTTSs occur in a more proximal location such as the elbow or knee. The diffuse variant tends to occur adjacent to the articular surfaces of the knee, hip, or foot. The diffuse variant is also sometimes termed pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS) when located in an intra-articular location such as the synovium (Figure 10.2.2). However, there clearly are some diffuse variants of giant cell tumor that occur outside of the joints, and without knowing the exact location of the lesion and/or imaging features, the distinction between these two entities can be problematic.

Both lesions tend to occur preferentially in adults, most commonly between 20 and 40 years old. The nodular or localized variant often presents as a slow-growing mass near a joint, with pain, swelling, and some limitation of motion as the presenting symptoms. On imaging, the localized version of tenosynovial giant cell tumor is usually identified as a discrete mass. It may cause focal erosion of the adjacent bone. The diffuse subtype often presents with similar symptoms. On imaging, this lesion is not well delineated and may contain peripheral calcifications.

Surgical excision is the mainstay of treatment for both forms of tenosynovial giant cell tumor. The localized form is usually well controlled with an adequate excision, whereas the diffuse form is more problematic. Local recurrences are relatively common with diffuse giant cell tumors, particularly if there is a positive excision margin on resection. Multiple recurrences often lead to significant morbidity and loss of joint function.

HISTOPATHOLOGY

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree