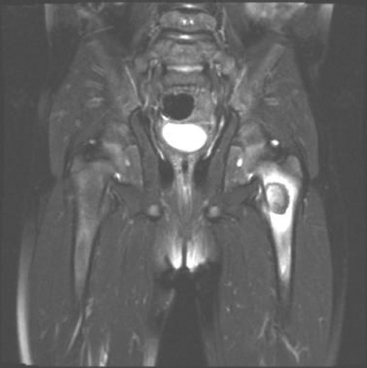

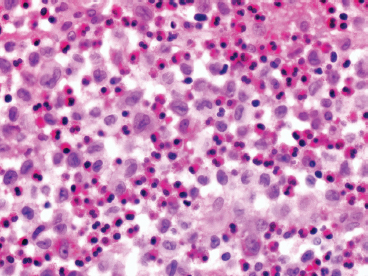

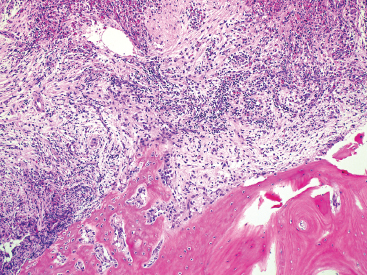

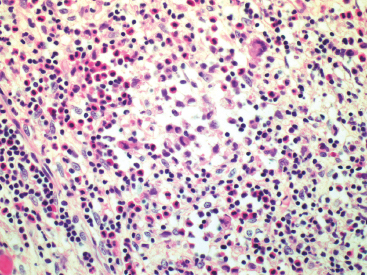

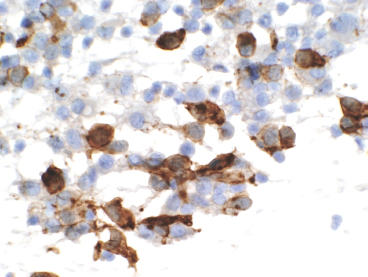

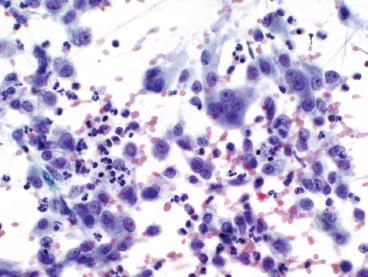

GIANT CELL-RICH LESIONS 17.1 Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (Eosinophilic Granuloma) 17.2 Giant Cell Lesion of Small Bones (Giant Cell Reparative Granuloma) 17.1 Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (Eosinophilic Granuloma) Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a clonal disorder of antigen-presenting, peripheral dendritic cells derived from a bone marrow precursor. These are thought to be immature Langerhans cells rather than true histiocytes. LCH encompasses a variety of clinical syndromes that vary from an isolated, localized nonsystemic form of disease affecting a single organ to a multifocal form affecting a single organ and finally to multifocal and multiorgan severe systemic disease. When localized to the bone, LCH is frequently termed eosinophilic granuloma (EG), a term that is clearly a misnomer but is still frequently used in clinical practice. When the lesion is more systemic or multifocal, LCH is sometimes known as either Hand-Schuller-Christian disease or Letterer-Siwe disease. All forms of LCH were also previously called Histiocytocysis X, a term, which has been abandoned for several years. Fortunately, the localized form of disease is by far the most common, and isolated foci of LCH confined to bone represent one of the most common and least severe forms of LCH. Isolated bone LCH has been reported in a wide age distribution, but tends to peak in younger individuals. Over half of the cases of isolated bone LCH are seen in children under 10. Males are twice more likely to be affected than females. Any bone may be affected, but there is a predilection for the bones of the skull. Other frequent sites of occurrence include the pelvis, diaphysis, and metaphyseal regions of the long bones and the vertebral bodies (Figure 17.1.1). Patients present with pain, swelling, and tenderness. In the mandible, LCH can be associated with loosening of the teeth. Back pain and scoliosis are often seen in association with LCH of the vertebral column. Imaging findings include a lytic lesion centered on the medullary cavity of the bone. There is often an extensive periosteal reaction. The radiographic differential diagnosis usually includes osteomyelitis and Ewing sarcoma. The prognosis for monostotic or polyostotic LCH is generally very favorable. Treatment options include simple observation, lesional curettage, or corticosteroid injection. Patients with the disseminated form of disease have a more guarded outcome. Systemic or multiorgan LCH can be fatal, particularly in very young children. To date, cytogenetic studies have shown recurrent abnormalities of chromosomes 1, 9, and 22. There is some evidence that LCH may be related to Merkel cell polyomavirus infection. The histologic picture of LCH is very distinctive. The Langerhans cells are admixed with a variety of other inflammatory cells including numerous histiocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils. In addition, occasional multinucleate, osteoclast-like giant cells are admixed in the lesion. This inflammatory infiltrate forms large nests or clusters of cells that often encase the host bone elements (Figure 17.1.2). The eosinophilic component of the infiltrate is often quite strikingly predominant; hence, the old term EG ascribed to this lesion (Figure 17.1.3). This inflammatory infiltrate often tends to overshadow the true Langerhans cell, which is the pathognomonic feature of this disorder. Langerhans cells are characteristically elongated in shape and contain a deep longitudinal nuclear indentation or cleft, which gives them a coffee bean appearance (Figure 17.1.4). Variable histologic features of LCH include the presence of focal fibrosis within the inflammatory foci as well as small foci of necrosis. The mitotic rate of LCH is often vey brisk, but atypical mitotic figures are not present. Likewise, pleomorphism is largely confined to the Langerhans cell population and aside from the strange coffee bean appearance, is usually minimal. Immunohistochemical staining is an invaluable adjunct to the morphologic diagnosis of LCH. The Langerhans cells express S100 protein antigen as well as the more specific markers CD1a and CD207 (langerin) (Figure 17.1.5). Older investigative techniques include the ultrastructural demonstration of intracytoplasmic “tennis racket”-shaped inclusions known as Birbeck granules on electron microscopy. LCH is a disorder that can be definitively diagnosed with confidence on cytology. This is due in large part to the distinctive appearance of the Langerhans cells on cytologic preparations. Of note, Giemsa-based stains, commonly used for immediate assessment, often fail to highlight the nuclear details (longitudinal indentations) that are so characteristic of the Langerhans cells. Instead, nuclear morphology should be assessed on ethanol-fixed material stained with either hematoxylin and eosin or Pap-type stains (Figure 17.1.6). Immunohistochemical confirmation by staining for CD1a and/or S100 protein can easily be performed on cell blocks prepared form aspirates or even on direct smears containing a Langerhans cell population. FIGURE 17.1.1 An isolated focus of Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), also known as eosinophilic granuloma (EG), in the metaphysis of the femur. The radiographic differential diagnosis almost always includes focal infection (Brodie’s abscess). FIGURE 17.1.2 LCH of the bone causes local destruction. There is often extensive edema and a periosteal reaction. FIGURE 17.1.3 LCH/EG of bone is composed of numerous eosinophils and other inflammatory cells. The eosinophilia often obscures the presence of the Langerhans histiocytes. Rare osteoclast-type giant cells are present as well. FIGURE 17.1.4 On high power, the characteristic features of the Langerhans cells can be identified. They often have irregular nuclear configurations, often with longitudinal grooves similar to those of coffee beans. FIGURE 17.1.5 Immunohistochemical staining for S100 protein or CD1a highlights the Langerhans cell element. FIGURE 17.1.6 The cytologic features of LCH are best demonstrated on fixed preparations. In this example, there is an osteoclast-type giant cell, inflammation, and histiocytes, some featuring irregular nuclear grooves. 17.2 Giant Cell Lesion of Small Bones (Giant Cell Reparative Granuloma) Giant cell reparative granuloma is also referred to as giant cell lesion of the small bones (GCLSB) or occasionally as a “solid” variant of aneurysmal bone cyst. Giant cell reparative granuloma is the preferred term for lesions of the craniofacial bones. GCLSB is a rare tumor that arises in the bones of the hands and feet. The metacarpal and metatarsal bones are more commonly affected than carpal or tarsal bones. GCLSB affects patients of all ages, but is distinctly more common in the second and third decades of life. Patients present with symptoms of pain and swelling in the tumor region and may often have an associated pathologic fracture. On imaging, GCLSB appears as an osteolytic and expansile lesion that tends to be centered on the metaphysis or diaphysis of the bone (Figures 17.2.1 and 17.2.2). The bone cortex is most often thin but intact, and a periosteal reaction is usually absent. On cross sectional imaging, there may be evidence of internal septation and cystic cavity formation. GCLSB is a benign lesion, but tends to be associated with a high rate of recurrence (up to 50%). To date, a few cases of GCLSB have been studied cytogenetically. All have shown cytogenetic alterations, but none appear to be reproducible. GCLSB that occur in the bones of the hands and feet contain USP6 rearrangements; giant cell reparative granulomas of the craniofacial bones do not.

HISTOPATHOLOGY

CYTOLOGIC FEATURES

HISTOPATHOLOGY

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Giant Cell-Rich Lesions