(1)

Department of Pathology, Rutgers-New Jersey Medical School, Newark, NJ, USA

Keywords

The requisition sheetAccessioningGross examinationProcessingEmbeddingCutting sectionsStainingLabelingRecuts and levels“Floaters” and contaminants“Rush” specimensSpecial studies and fixationFrozen sections: uses and limitationsSpecial studiesSlide review1.1 The Anatomic Pathology Laboratory

What happens when a surgical specimen reaches the pathology laboratory? A quick tour is in order and will help explain timing of receipt of results by clinicians, as well as what is needed from clinicians to assist with diagnosis. There are a number of steps, all of which have processes in place in the laboratory to avoid error. These include accessioning, gross dissection, processing, embedding, cutting of sections, staining, and labeling [1].

1.1.1 The Requisition Sheet

It is important for the clinician to provide a pertinent clinical history in addition to the usual demographics, which would include patient age and gender. This does not “prejudice” the pathologist, but allows for the best interpretation (Table 1.1). Slides from prior procedures, if within the same institution, are often reviewed, particularly in cases of malignancy, and so prior history of related surgery should be indicated. If the prior surgery occurred at a different institution, slides can be obtained for review, if necessary for diagnosis. This is particularly recommended in oncology cases, where often the biopsy occurs at one hospital, and the definitive surgery at another. Items to put on the requisition sheet include parity, the reason for the procedure, last menstrual period if pertinent, related medications (such as progestational agents, which may alter endometrium), prior therapy such as radiation or chemotherapy, which can induce tissue changes, and orientation of the specimen as applicable. This is particularly important in cases such as a vulvar excision for VIN, where re-excision of a positive margin may rest on where the positive margin was located. In addition, any specific requests the clinician has for the pathologist should be noted, i.e., “please rule out toxoplasmosis” for a patient with a pregnancy loss and a history of cats in the house.

Table 1.1

Information needed by pathologist and clinician

Information the pathologist needs from the clinician |

• Pertinent clinical history |

Age, parity, date of last menstrual period |

Why procedure is being performed |

Any prior surgery relating to the current disease process? |

Orientation of specimen as appropriate |

Any pertinent medications? |

Any prior therapy? |

Any specific questions? |

Information the clinician needs from the pathologist |

• Short turnaround time |

• Understandable report that can be discussed with patient |

• Findings in format that can be correlated with clinical findings |

1.1.2 Accessioning

The case is given a unique requisition number on arrival, which usually has the year, and then the unique identifier (i.e., S14-12,345, where S stands for surgical). This involves checking both the specimen jar and the requisition, to make sure they match the correct (same) patient, and creation of a computer record of the specimen. Each jar received on a case gets a separate subdesignation (i.e., S14-12345A, S14-12345B) and a separate diagnosis within the report. If two fragments of tissue are in the same jar (i.e., 2 cervical biopsies), it will not be possible to distinguish which came from where. Similarly, if adnexae are submitted detached from the uterus, laterality will not be possible to assign if they arrive in the uterine bucket. Separate jars with designation should be used if separate cervical diagnoses, or adnexal laterality matters in such cases.

1.1.3 Gross Examination

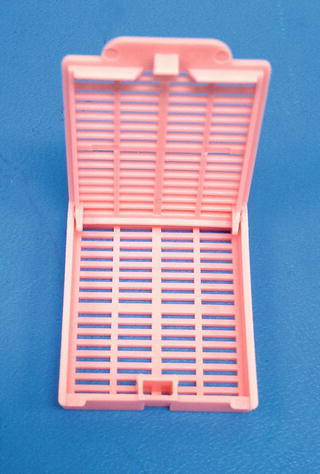

Gross examination involves the initial examination of the specimen, which includes measuring, and possibly weighing, and describing what is seen by the naked eye. A description is created which goes into the report, separate from the final diagnosis. An example from a leiomyomatous uterus can be seen in Table 1.2. The specimen is again checked for identification and labeling at this point. Pertinent areas of the specimen are selected for processing and slide preparation. For small specimens, such as biopsies, the tissue is usually entirely submitted. For larger specimens, representative sections are submitted, after being cut to fit into tissue cassettes, which are small plastic boxes with lids. Whether the tissue is entirely submitted or representative sections are submitted is noted in the gross description, as well as a list of what is in each tissue cassette (Fig. 1.1). For representative sectioning, additional sections can be submitted after initial slide review for the period of time the laboratory keeps specimens. An example would be additional tissue submitted to identify endometrium in a morcellated uterus. Specimens are usually kept for a period of time after a case is signed out. Inking of the specimen may occur if margins are important, as the ink used survives processing, and can be seen on the slides. If there is tumor at the ink, the margin is considered positive. Some specimens may need to be fixed in formalin prior to selecting areas for submission, which may introduce additional time into receipt of diagnosis by the clinician. An example is a cone biopsy, which is difficult to cut into well-oriented sections fresh.

Table 1.2

Sample gross description

• Cassette A1—anterior cervix |

• Cassette A2—posterior cervix |

• Cassette A3—anterior lower uterine segment |

• Cassette A4—posterior lower uterine segment |

• Cassette A5—anterior endomyometrium |

• Cassette A6—posterior endomyometrium |

• Cassette A7—largest mass, possible portion which was protruding through cervix |

• Cassettes A8–A9—largest mass, two (2) sections |

• Cassette A10—smaller masses |