Chapter 1 General Appearance, Facies, and Body Habitus

General Appearance

2 Which aspects of the patient should be assessed?

Body habitus and body proportions

Body habitus and body proportions

Alertness and state of consciousness

Alertness and state of consciousness

Degree of illness, whether acute or chronic

Degree of illness, whether acute or chronic

A. Posture

3 What information can be obtained from observing the patient’s posture?

In abdominal pain the posture is often so typical as to localize the disease:

Patients with pancreatitis usually lie in the fetal position: on one side, with knees and legs bent over.

Patients with pancreatitis usually lie in the fetal position: on one side, with knees and legs bent over.

Patients with peritonitis are very still and avoid any movement that might worsen the pain.

Patients with peritonitis are very still and avoid any movement that might worsen the pain.

Patients with intestinal obstruction are instead quite restless.

Patients with intestinal obstruction are instead quite restless.

Patients with renal or perirenal abscesses bend toward the side of the lesion.

Patients with renal or perirenal abscesses bend toward the side of the lesion.

Patients who lie supine, with one knee flexed and the hip externally rotated, are said to have the “psoas sign.” This reflects either a local abnormality around the iliopsoas muscle (such as an inflamed appendix, diverticulum, or terminal ileum from Crohn’s disease) or inflammation of the muscle itself. In the olden days, the latter was due to a tuberculous abscess, originating in the spine and spreading down along the muscle. Such processes were referred to as “cold abscesses” because they had neither warmth nor other signs of inflammation. Now, the most common cause of a “psoas sign” is intramuscular bleeding from anticoagulation.

Patients who lie supine, with one knee flexed and the hip externally rotated, are said to have the “psoas sign.” This reflects either a local abnormality around the iliopsoas muscle (such as an inflamed appendix, diverticulum, or terminal ileum from Crohn’s disease) or inflammation of the muscle itself. In the olden days, the latter was due to a tuberculous abscess, originating in the spine and spreading down along the muscle. Such processes were referred to as “cold abscesses” because they had neither warmth nor other signs of inflammation. Now, the most common cause of a “psoas sign” is intramuscular bleeding from anticoagulation.

Patients with meningitis lie like patients with pancreatitis: on the side, with neck extended, thighs flexed at the hips, and legs bent at the knees—juxtaposed like the two bores of a double-barreled rifle.

Patients with meningitis lie like patients with pancreatitis: on the side, with neck extended, thighs flexed at the hips, and legs bent at the knees—juxtaposed like the two bores of a double-barreled rifle.

Patients with a large pleural effusion tend to lie on the affected side to maximize excursions of the unaffected side. This, however, worsens hypoxemia (see Chapter 13, questions 48–51).

Patients with a large pleural effusion tend to lie on the affected side to maximize excursions of the unaffected side. This, however, worsens hypoxemia (see Chapter 13, questions 48–51).

Patients with a small pleural effusion lie instead on the unaffected side (because direct pressure would otherwise worsen the pleuritic pain).

Patients with a small pleural effusion lie instead on the unaffected side (because direct pressure would otherwise worsen the pleuritic pain).

Patients with a large pericardial effusion (especially tamponade) sit up in bed and lean forward, in a posture often referred to as “the praying Muslim position.” Neck veins are greatly distended.

Patients with a large pericardial effusion (especially tamponade) sit up in bed and lean forward, in a posture often referred to as “the praying Muslim position.” Neck veins are greatly distended.

Patients with tetralogy of Fallot often assume a squatting position, especially when trying to resolve cyanotic spells—such as after exercise.

Patients with tetralogy of Fallot often assume a squatting position, especially when trying to resolve cyanotic spells—such as after exercise.

4 What is the posture of patients with dyspnea?

An informative alphabet soup of orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, platypnea and orthodeoxia, trepopnea, respiratory alternans, and abdominal paradox. These can determine not only the severity of dyspnea, but also its etiology (see Chapter 13, questions 35–51).

B. State of Hydration

5 What is hypovolemia?

A condition characterized by volume depletion and dehydration:

Volume depletion is a loss in extracellular salt, through either kidneys (diuresis) or the gastrointestinal tract (hemorrhage, vomiting, diarrhea). This causes contraction of the total intravascular pool of plasma, which results in circulatory instability and thus an increase in the serum urea nitrogen-to-creatinine ratio—a valuable biochemical marker for volume depletion.

Volume depletion is a loss in extracellular salt, through either kidneys (diuresis) or the gastrointestinal tract (hemorrhage, vomiting, diarrhea). This causes contraction of the total intravascular pool of plasma, which results in circulatory instability and thus an increase in the serum urea nitrogen-to-creatinine ratio—a valuable biochemical marker for volume depletion.

Dehydration is instead a loss of intracellular water. It eventually causes cellular desiccation and an increase in serum sodium and plasma osmolality, two useful biochemical markers.

Dehydration is instead a loss of intracellular water. It eventually causes cellular desiccation and an increase in serum sodium and plasma osmolality, two useful biochemical markers.

9 How do you determine the presence of hypovolemia?

Through the “tilt test,” which measures postural changes in heart rate and blood pressure (BP):

1. Ask the patient to lie supine.

3. Measure heart rate and blood pressure in this position.

6. Measure heart rate and then blood pressure while the patient is standing. Measure rate by counting over 30 seconds and multiplying by two, which is more accurate than counting over 15 seconds and multiplying by four.

12 Should the patient lie supine for more than 2 minutes before standing up?

No. A longer period does not increase the sensitivity of the test.

14 What is the normal response to the tilt test?

Going from supine to standing, a normal patient exhibits the following:

Heart rate increases by 10.9 ± 2 beats/minute and usually stabilizes after 45–60 seconds.

Heart rate increases by 10.9 ± 2 beats/minute and usually stabilizes after 45–60 seconds.

Systolic blood pressure decreases only slightly (by 3.5 ± 2 mmHg) and stabilizes in 1–2 minutes.

Systolic blood pressure decreases only slightly (by 3.5 ± 2 mmHg) and stabilizes in 1–2 minutes.

Diastolic blood pressure increases by 5.2 ± 2.4 mmHg. This, too, stabilizes within 1–2 minutes.

Diastolic blood pressure increases by 5.2 ± 2.4 mmHg. This, too, stabilizes within 1–2 minutes.

18 So what are the findings of a positive tilt test for hypovolemia?

The most helpful is a postural increase in heart rate of at least 30 beats/minute (which has a sensitivity of 97% and a specificity of 96% for blood loss >630 mL). This change (as well as severe postural dizziness, see later) may last 12–72 hours if IV fluids are not administered.

The most helpful is a postural increase in heart rate of at least 30 beats/minute (which has a sensitivity of 97% and a specificity of 96% for blood loss >630 mL). This change (as well as severe postural dizziness, see later) may last 12–72 hours if IV fluids are not administered.

The second most helpful finding is postural dizziness so severe to stop the test. This has the same sensitivity and specificity as tachycardia. Mild postural dizziness, instead, has no value.

The second most helpful finding is postural dizziness so severe to stop the test. This has the same sensitivity and specificity as tachycardia. Mild postural dizziness, instead, has no value.

Hypotension of any degree while standing has little value unless associated with dizziness. In fact, an orthostatic drop in systolic BP >20 mmHg unassociated with dizziness can occur in one third of patients >65 years old and 10% of younger subjects, with or without hypovolemia.

Hypotension of any degree while standing has little value unless associated with dizziness. In fact, an orthostatic drop in systolic BP >20 mmHg unassociated with dizziness can occur in one third of patients >65 years old and 10% of younger subjects, with or without hypovolemia.

Supine hypotension (systolic BP <95 mmHg) and tachycardia (>100/min) may be absent, even in patients with blood losses >1 L. Hence, although quite specific for hypovolemia when present, supine hypotension and tachycardia have low sensitivity; they are present in one tenth of patients with moderate blood loss and in one third with severe blood loss. Paradoxically, blood-loss patients may even present with bradycardia as a result of a vagal reflex.

Supine hypotension (systolic BP <95 mmHg) and tachycardia (>100/min) may be absent, even in patients with blood losses >1 L. Hence, although quite specific for hypovolemia when present, supine hypotension and tachycardia have low sensitivity; they are present in one tenth of patients with moderate blood loss and in one third with severe blood loss. Paradoxically, blood-loss patients may even present with bradycardia as a result of a vagal reflex.

29 What is the significance of dry mucous membranes in children?

Mild depletion corresponds to <5% intravascular contraction (i.e., <50 mL/kg loss of body weight). This is usually determined by history alone, since physical signs are minimal or absent. Mucosae are moist, skin turgor and capillary refill normal, and pulse slightly increased.

Mild depletion corresponds to <5% intravascular contraction (i.e., <50 mL/kg loss of body weight). This is usually determined by history alone, since physical signs are minimal or absent. Mucosae are moist, skin turgor and capillary refill normal, and pulse slightly increased.

Moderate depletion corresponds instead to 100 mL/kg loss of body weight. Mucosae are dry, skin turgor reduced, pulses weak, and patients are tachycardic and hyperpneic.

Moderate depletion corresponds instead to 100 mL/kg loss of body weight. Mucosae are dry, skin turgor reduced, pulses weak, and patients are tachycardic and hyperpneic.

Severe depletion corresponds to >100 mL/kg loss of body weight. All previous signs are present, plus cold, dry, and mottled skin; altered sensorium; prolonged refill time; weak central pulses; and, eventually, hypotension.

Severe depletion corresponds to >100 mL/kg loss of body weight. All previous signs are present, plus cold, dry, and mottled skin; altered sensorium; prolonged refill time; weak central pulses; and, eventually, hypotension.

C. State of Nutrition

33 Why is the BMI important?

Because a high BMI is associated with increased risk for serious medical problems:

Various cancers (including endometrial, breast, prostate, and colon) are more common in obese subjects (in one study, 52% higher rates in men and 62% in women).

Various cancers (including endometrial, breast, prostate, and colon) are more common in obese subjects (in one study, 52% higher rates in men and 62% in women).

Miscellaneous conditions, such as lower extremity venous stasis, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux, urinary stress incontinence, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis, sleep apnea, and respiratory problems

Miscellaneous conditions, such as lower extremity venous stasis, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux, urinary stress incontinence, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis, sleep apnea, and respiratory problems

Note that body weight has a U-shaped relationship with mortality, causing an increase when either very low or very high.

Note that body weight has a U-shaped relationship with mortality, causing an increase when either very low or very high.

38 How important is the distribution of body fat?

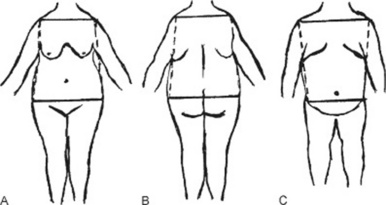

Very important, since it strongly determines the impact of obesity on health. Fat deposition may be central (mostly in the trunk) or peripheral (mostly in the extremities) (Fig. 1-1).

Central obesity has a bihumeral diameter greater than the bitrochanteric diameter; subcutaneous fat has a “descending” distribution, being mostly concentrated in the upper half of the body (neck, cheeks, shoulder, chest, and upper abdomen).

Central obesity has a bihumeral diameter greater than the bitrochanteric diameter; subcutaneous fat has a “descending” distribution, being mostly concentrated in the upper half of the body (neck, cheeks, shoulder, chest, and upper abdomen).

Peripheral obesity has instead a bitrochanteric diameter greater than the bihumeral diameter; subcutaneous fat has an “ascending” distribution, being mostly concentrated in the lower half of the body (lower abdomen, pelvic girdle, buttocks, and thighs).

Peripheral obesity has instead a bitrochanteric diameter greater than the bihumeral diameter; subcutaneous fat has an “ascending” distribution, being mostly concentrated in the lower half of the body (lower abdomen, pelvic girdle, buttocks, and thighs).

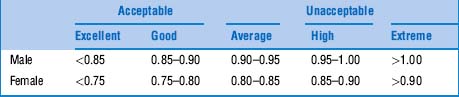

42 What is the WHR threshold for cardiovascular risk?

The cutoff seems to be a waist-to-hip ratio of 0.83 for women and 0.9 for men. Favoring WHR over BMI would result in a threefold increase in the population at risk for myocardial infarction. This would be especially valuable in Asia, where obesity by BMI is rare, but WHRs can be quite abnormal (Table 1-1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree