73

Gastrointestinal Tract Infections

CHAPTER CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Infections with a variety of agents can occur in any part of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract from the mouth to the anal canal. Infections can range in severity from self-limited to life-threatening, particularly if infection spreads from the gut to other parts of the body. Infections are typically caused by the ingestion of exogenous pathogens in sufficient quantities to evade host defenses and then cause disease by multiplication, toxin production, or invasion through the gastrointestinal mucosa to reach the bloodstream and other tissues. In other cases, members of the normal flora of the GI tract can cause disease.

ESOPHAGITIS

Definition

Esophagitis is an inflammatory process that can damage the esophagus.

Pathophysiology

Inflammation caused by infection, typically by fungi such as Candida or viruses such as herpes simplex virus, causes the symptoms of esophagitis. Most cases occur in immunocompromised patients, especially those with reduced cell-mediated immunity. The extent of damage to the esophagus is typically related to the severity of symptoms.

Clinical Manifestations

Odynophagia (pain on swallowing) and dysphagia (difficulty in swallowing) are the key clinical manifestations of esophagitis.

Pathogens

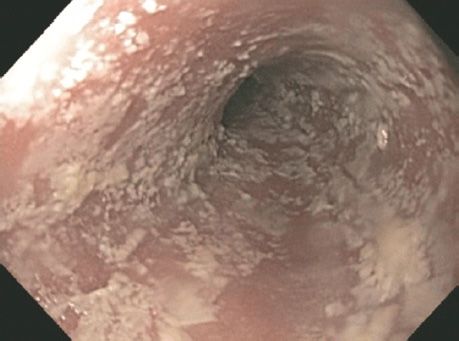

Candida is the most common etiology, particularly among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients and other immunocompromised hosts (Figure 73–1). Less common pathogens include herpesviruses such as cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus. Noninfectious causes also occur, such as acid reflux from the stomach and medication-induced disease (e.g., doxycycline).

FIGURE 73–1 Candida esophagitis. Note the many whitish lesions on the esophageal mucosa seen on endoscopy. (Reproduced with permission from McKean SC et al. Principles and Practice of Hospital Medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2012. Copyright © 2012 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.)

Diagnosis

Diagnosis may be empiric after a trial of fluconazole results in improvement for presumed Candida esophagitis. If an empiric course of fluconazole does not work, then endoscopy for visualization and biopsy could be helpful, particularly in immunocompromised hosts. Biopsy samples should be analyzed by using pathologic and microbiologic tests.

Treatment

In a typical patient (e.g., HIV-infected patient) presenting with odynophagia and retrosternal pain, an empiric diagnosis of esophageal candidiasis is made and fluconazole therapy instituted. If there is no effect on symptoms and if Candida resistance is not suspected, then further diagnostics as outlined earlier may identify a specific organism that could be targeted for treatment.

Prevention

One option to prevent recurrent esophageal candidiasis is by using fluconazole prophylaxis. However, this is not generally advised given the high risk of selecting for fluconazole-resistant Candida. Immune restoration in HIV-infected patients may decrease the incidence of esophageal and oropharyngeal candidiasis.

GASTRITIS

Definition

Gastritis refers to inflammation of the mucosa of the stomach. It may be erosive or nonerosive, depending on histologic and endoscopic findings. A break in the gastric and adjacent duodenal mucosa defines peptic ulcer disease.

Pathophysiology

The mechanism by which one of the main pathogens, Helicobacter pylori causes peptic ulcer disease has been largely elucidated. Following attachment to the gastric mucosa, H. pylori causes direct mucosal damage by the combination of ammonia production (from the action of the organism’s urease on urea) and the host inflammatory response. The ability of the organism to survive is enhanced by the neutralization of the stomach’s acid by the ammonia produced.

Clinical Manifestations

Patients with gastritis typically complain of dyspepsia (epigastric pain, burning), nausea, and vomiting. In the case of peptic ulcer disease, epigastric pain is the primary symptom. Some patients may report alleviation of pain with food, particularly those with duodenal ulcers. Gastrointestinal bleeding is a complication of peptic ulcer disease. Some patients with gastritis may be asymptomatic.

Pathogens

Infectious and noninfectious etiologies are possible. Among infectious causes, H. pylori is the most important. Viruses such as cytomegalovirus and fungi such as Mucor may rarely cause ulcer disease as well, particularly among immuncompromised patients. Following ingestion of raw fish, larvae of Anisakis species may become embedded in the gastric mucosa and cause severe abdominal pain. Mycobacteria (tuberculosis and nontuberculosis mycobacteria), Giardia, and Strongyloides may also cause gastritis. Noninfectious causes such as alcohol and medications (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) are also implicated.

Diagnosis

Upper endoscopy with gastric biopsy is the definitive diagnostic strategy. If abnormal findings are detected, pathologic analysis and further directed testing may be performed. For the most common infectious cause of peptic ulcer disease, H. pylori–associated ulcers can be confirmed using a urease test on the biopsy specimen or using noninvasive tests such as the urea breath test or stool antigen test.

Treatment

Treatment is directed at the underlying pathogen, taking the host immune status into consideration. For H. pylori, combination therapy with two antibiotics, such as ampicillin and clarithromycin, plus a proton pump inhibitor, such as omeprazole, or bismuth is used with varying success.

DIARRHEA (GASTROENTERITIS, ENTEROCOLITIS)

Definition

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree