Patient Story

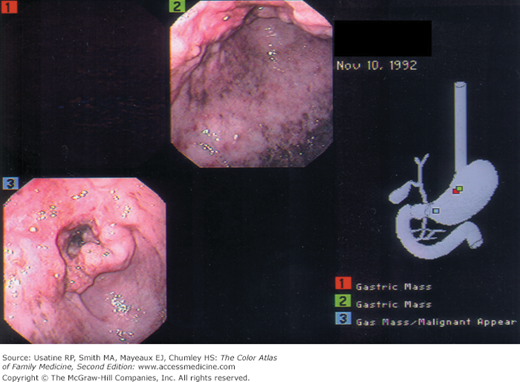

A 72-year-old Japanese immigrant was brought in by his family with complaints of difficulty in eating, vague abdominal pain, and weight loss. Endoscopy and biopsy confirmed gastric adenocarcinoma (Figure 60-1). Liver metastases were found on abdominal CT. The family and the patient chose only comfort measures and the patient died 6 months later.

Epidemiology

- Based on Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data, an estimated 12,730 men and 8270 women will be diagnosed with gastric cancer, and 10,570 men and women will die of this cancer in 2012 (2010).1 The median age at diagnosis is 70 years and median age at death from gastric cancer is 73 years.1

- Stomach cancer occurs in 10.8 per 100,000 men and 5.4 per 100,000 women in a year. In 2008, the United States prevalence was 37,739 men and 28,271 women, with a lifetime risk of 0.88%.1

- High rates of stomach cancer occur in Japan, China, Chile, and Ireland.2

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Eighty-five percent of stomach cancers are adenocarcinomas with 15% lymphomas and GI stromal tumors.2 Adenocarcinoma is further divided into two types:

- Diffuse type—Characterized by absent cell cohesion, these tumors affect younger individuals infiltrating and thickening the stomach wall; the prognosis is poor. Several susceptibility genes have been identified for this type of cancer.3

- Intestinal type—Characterized by adhesive cells forming tubular structures, these tumors frequently ulcerate.

- Diffuse type—Characterized by absent cell cohesion, these tumors affect younger individuals infiltrating and thickening the stomach wall; the prognosis is poor. Several susceptibility genes have been identified for this type of cancer.3

- Tumor grade can be well (4.1%), moderate (23.1%), or poorly differentiated (54.9%), or undifferentiated (2.9%) (SEER data from 1988-2001; unknown type accounted for 15%).4

- Most tumors are thought to arise from ingestion of nitrates that are converted by bacteria to carcinogens. Exogenous and endogenous factors (see “Risk Factors” below) contribute to this process.2

- Exogenous sources of nitrates—Sources include foods that are dried, smoked, and salted. Helicobacter pylori infection may contribute to carcinogenicity by creating gastritis, loss of acidity, and bacterial growth.

- Oncogenic pathways identified in most gastric cancers are the proliferation/stem cell, nuclear factor-κB, and Wnt/β-catenin; interactions between them appear to influence disease behavior and patient survival.5

- Gastric tumors are classified for staging using the T (tumor) N (nodal involvement) M (metastases) system. Two important prognostic factors are depth of invasion through the gastric wall (less than T2 [tumor invades muscularis propria]) and presence or absence of regional lymph node involvement (N0). Changes made to the classification system in the seventh edition of the American Joint Commission’s Cancer Staging Manual for gastric cancer6 demonstrate better survival discrimination.7

- Gastric cancer spreads in multiple ways:2

- Local extension through the gastric wall to the perigastric tissues, omenta, pancreas, colon, or liver.

- Lymphatic drainage through numerous pathways leads to multiple nodal group involvement (e.g., intraabdominal, supraclavicular) or seeding of peritoneal surfaces with metastatic nodules occurring on the ovary, periumbilical region, or peritoneal cul-de-sac.

- Hematogenous spread is also common with liver metastases.

- Local extension through the gastric wall to the perigastric tissues, omenta, pancreas, colon, or liver.

- Exogenous sources of nitrates—Sources include foods that are dried, smoked, and salted. Helicobacter pylori infection may contribute to carcinogenicity by creating gastritis, loss of acidity, and bacterial growth.

Risk Factors

- Previous gastric surgery—As a result of alteration of the normal pH or with biopsy showing high-grade dysplasia.2,8

- Other endogenous risk factors—Atrophic gastritis (including postsurgical vagotomized patients) and pernicious anemia are conditions that favor the growth of nitrate-converting bacteria. In addition, intestinal-type cells that develop metaplasia and possibly atypia can replace the gastric mucosa in these patients. Genetic polymorphisms (e.g., interleukin-1B-511, interleukin-1RN, and tumor necrosis factor-α) also appear to play a role. Familial adenomatous polyposis and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer are also risk factors.8

- Individuals infected with certain H. pylori bacteria (cytotoxin-associated gene A) are at increased risk of gastric adenocarcinoma (especially noncardia) and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma.9

- Additional risk factors—Smoking, low socioeconomic class, lower educational level, exposure to certain pesticides (e.g., those who work in the citrus fruit industry in fields treated with 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid [2,4-D], chlordane, propargite, and triflurin10), radiation exposure, and blood type A.

Diagnosis

- Asymptomatic, if superficial and/or early.

- Upper abdominal pain that ranges from vague to severe.

- Postprandial fullness.

- Anorexia and mild nausea are common.

- Nausea and vomiting occur with pyloric tumors.

- Late symptoms include weight loss and a palpable mass (regional extension).

- Late complications include peritoneal and pleural effusions; obstruction of the gastric outlet; bleeding from esophageal varices or postsurgical site; and jaundice.11

- Physical signs are also late features and include:11

- Palpable enlarged stomach with succussion splash (splashing sound on shaking, indicative of the presence of fluid and air in a body cavity).

- Primary mass (rare).

- Enlarged liver.

- Enlarged, firm to hard, lymph nodes (i.e., left supraclavicular [Virchow]), periumbilical region (Sister Mary Joseph node), and peritoneal cul-de-sac (Blumer shelf; palpable on vaginal or rectal examination).

- Palpable enlarged stomach with succussion splash (splashing sound on shaking, indicative of the presence of fluid and air in a body cavity).

- Based on SEER data from 1988-2001, gastric tumors occur most often in the cardia (25.5%) and gastric antrum (20.7%), followed by the lesser curvature (9.9%), body (7.4%) and greater curvature (4.3%), and fundus (4.1%). Overlapping lesions were reported in 9.8% and no specific information was available in 15.2%.4

- Rates of noncardia gastric cancer appear to be decreasing.9

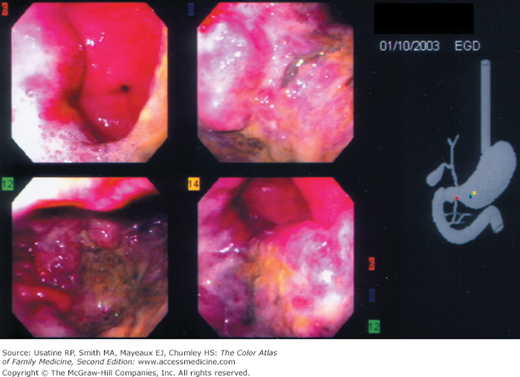

- Diagnosis can be made on endoscopy (Figures 60-1 and 60-2) with biopsy of suspicious lesions. Confocal laser endomicroscopy may improve detection of early lesions.12

- Urgent referral for endoscopy (within 2 weeks) is recommended for patients with dyspepsia who also have GI bleeding, dysphagia, progressive unexplained weight loss, persistent vomiting, iron-deficiency anemia, epigastric mass, family history of gastric cancer (onset <50 years), or whose dyspepsia is persistent and they are older than age 55 years.13 SOR C

- Double-contrast radiography is an alternative to endoscopy and can detect large primary tumors but distinguishing benign from malignant disease is difficult.2

- Although endoscopy is not necessary when radiography demonstrates a benign-appearing ulcer with evidence of complete healing at 6 weeks, some authors recommend routine endoscopy, biopsy, and brush cytology when any gastric ulcer is identified.2

- Some gastric polyps (adenomas, hyperplastic) have malignant potential and should be removed.14

- Work-up for metastases includes:15 SOR C

- Chest radiograph.

- CT scan or MRI of the abdomen and pelvis.

- Chest radiograph.

- Endoscopic sonography is useful as a staging tool when the CT scan fails to find evidence of locally advanced or metastatic disease.2

- A hemoglobin or hematocrit can identify anemia, present in approximately 30% of patients.11

- Electrolyte panels and liver function tests can assist in assessing the patient’s clinical state and any liver involvement.11

- Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is increased in about half of cases.11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree