CHAPTER 26 Functional Anatomy and General Principles of Regulation in the Gastrointestinal Tract

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract consists of the alimentary tract from the mouth to the anus and includes the associated glandular organs that empty their contents into the tract. The overall function of the GI tract is to absorb nutrients and water into the circulation and eliminate waste products. The major physiological processes that occur in the GI tract are motility, secretion, digestion, and absorption. Most of the nutrients in the diet of mammals are taken in as solids and as macromolecules that are not readily transported across cell membranes to enter the circulation. Thus, digestion consists of physical and chemical modification of food such that absorption can occur across intestinal epithelial cells. Digestion and absorption require motility of the muscular wall of the GI tract to move the contents along the tract and to mix the food with secretions. Secretions from the GI tract and associated organs consist of enzymes, biological detergents, and ions that provide an intraluminal environment optimized for digestion and absorption. These physiological processes are highly regulated to maximize digestion and absorption, and the GI tract is endowed with complex regulatory systems to ensure that this occurs. In addition, the GI tract absorbs drugs administered by the oral or rectal routes.

FUNCTIONAL ANATOMY

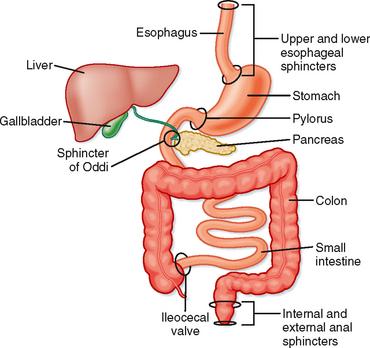

The structure of the GI tract varies greatly from region to region, but there are common features in the overall organization of the tissue. Essentially, the GI tract is a hollow tube divided into major functional segments; the major structures along the tube are the mouth and pharynx, esophagus, stomach, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, colon, rectum, and anus (Fig. 26-1). Together, the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum make up the small intestine, and the colon is sometimes referred to as the large intestine. Associated with the tube are blind-ending glandular structures that are invaginations of the lining of the tube; these glands empty their secretions into the gut lumen (e.g., Brunner’s glands in the duodenum, which secrete copious amounts of HCO3−). Additionally, there are glandular organs attached to the tube via ducts through which secretions empty into the gut lumen, for example, the salivary glands and the pancreas.

The blood supply to the intestine is important for carrying absorbed nutrients to the rest of the body. Unlike other organ systems of the body, venous drainage from the GI tract does not return directly to the heart but first enters the portal circulation leading to the liver. Thus, the liver is unusual in receiving a considerable part of its blood supply from other than the arterial circulation. GI blood flow is also notable for its dynamic regulation; splanchnic blood flow receives about 25% of cardiac output, an amount disproportionate to the mass of the GI tract that it supplies. After a meal, blood can also be diverted from muscle to the GI tract to subserve the metabolic needs of the gut wall and also to remove absorbed nutrients.

Cellular Specialization

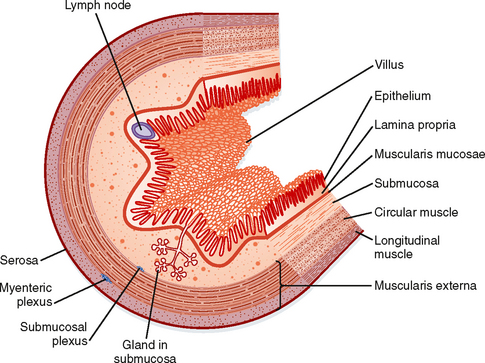

The wall of the tubular gut is made up of layers consisting of specialized cells (Fig. 26-2).

Mucosa

The columnar epithelial cells are linked together by intercellular connections called tight junctions. These junctions are complexes of intracellular and transmembrane proteins, and the tightness of these junctions is regulated throughout the postprandial period. The nature of the epithelium varies greatly from one part of the digestive tract to another, depending on the predominant function of that region. For example, the intestinal epithelium is designed for absorption; these cells mediate selective uptake of nutrients, ions, and water. In contrast, the esophagus has a squamous epithelium that has no absorptive role. It is a conduit for the transportation of swallowed food and thus needs some protection from rough food such as fiber, which is provided by the squamous epithelium.

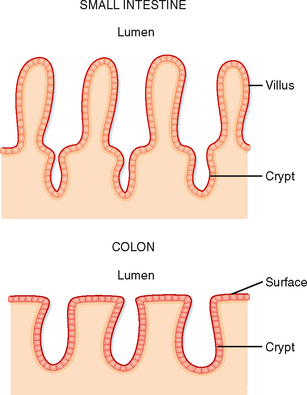

The surface area of the epithelium is arranged into villi and crypts (Fig. 26-3). Villi are finger-like projections that serve to increase the surface area of the mucosa. Crypts are invaginations or folds in the epithelium. The epithelium lining the GI tract is continuously renewed and replaced by dividing cells; in humans, this process takes about 3 days. These proliferating cells are localized to the crypts, where there is a proliferative zone of intestinal stem cells.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree