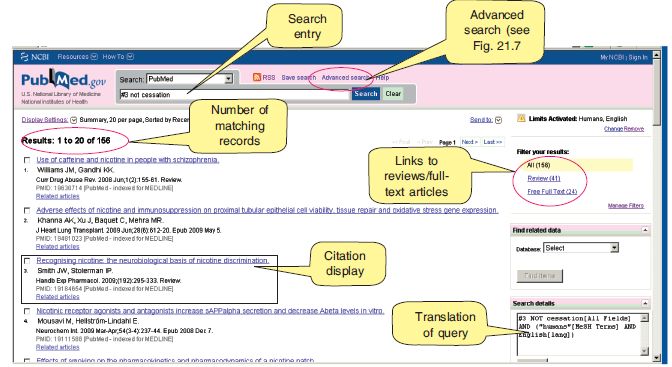

Figure 21.1. The main search page of MEDLINE®.

Scenario

The following example is used in order to illustrate how to refine searching techniques to get the most out of a search in the shortest possible time. Consider that you have been asked to write a review article on ‘Drug interactions with nicotine’, an article aimed at analysing how the metabolism, pharmacokinetics, toxicity and dose regimen of drugs would be affected by nicotine within the patient’s system.

Following the steps outlined in the ‘Taking the first steps’ section we will begin to define the search parameters:

Literature Search

In our outlined scenario above, it is fairly simple to decide where to start searching as we have two easily identified key concepts in ‘nicotine’ and ‘drug interaction’. Let us start with a basic search.

Basic Search

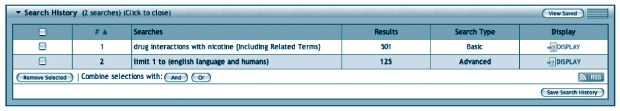

Basic Search in MEDLINE® is a good starting point, especially for inexperienced searchers. It allows you to do a natural language search by typing in a sentence that describes what you want; approximately 500–1,000 references are retrieved, ranked by relevance. After clicking on the Basic Search tab we searched using a simple phrase ‘Drug interactions with nicotine’ that returned 501 results (Search 1, Figure 21.2). We then refined our results by limiting to English language articles and those focusing on humans. This returned 125 articles (Search 2, Figure 21.2), a figure that lies within the numerical parameters previously outlined for a review article. Examining the first few pages of results, a number of references seemed relevant but it would be unwise to rely on the results of just one basic search when writing a review article. With Basic Search, always consider alternative ways to say the same thing, as typing slightly different phrases can lead to different results. Once you have exhausted the possibilities in Basic Search, move on to the advanced search techniques.

Advanced Search

Our advanced searches were based on two separate methods, one that used the subject headings assigned to references on MEDLINE® from the list of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and one that used a keyword approach.

Advanced Search Using Subject Headings

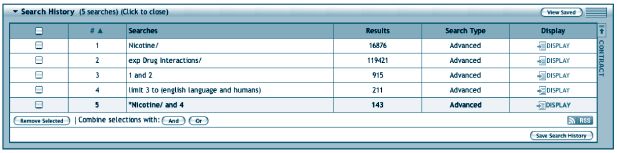

Step 1: We moved into Advanced Search mode by clicking the tab, then typed ‘nicotine’ into the search box and clicked on Search. With the ‘Map Term to Subject Heading’ option box ticked, the system automatically looks for one or more subject headings related to the search term and displays them on the Mapping Display screen. Nicotine turned out to be the subject heading for this topic; but remember that for other searches, the subject heading may not match what you type. For example, if you type paracetamol, the subject heading displayed is ‘acetaminophen’, another term for the same drug. Acetaminophen is the preferred MeSH subject heading, assigned to articles about this drug regardless of the name used by the authors. In addition, more than one subject heading may be shown, in which case you must decide which is most appropriate. We chose to include all subheadings and continue. This returned 16,876 results (Search 1, Figure 21.3). Notice the search term appears as ‘Nicotine/’—the slash indicates we included all subheadings.

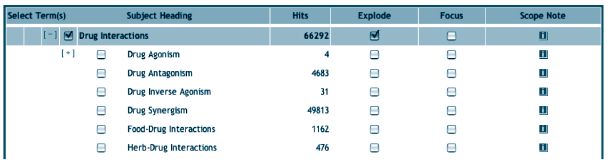

Step 2: We now searched ‘Drug interactions’, again with the ‘Map Term to Subject Heading’ option selected. ‘Drug interactions’ also turned out to be a subject heading. This time we decided to take a look at the tree before proceeding (it is recommended that users do this). Simply click on a subject heading to go to the tree screen for that heading. Scroll down the tree to find ‘Drug interactions’ highlighted in blue and to see the narrower terms which are available for specific types of drug interactions—Drug antagonism, Drug Synergism, etc. (Figure 21.4). Choose as many or as few terms as you wish. We decided to include them all. The easiest way to do so is to tick the explode box on the right beside ‘Drug interactions’ and click continue to proceed. This resulted in 119,421 results (Search 2, Figure 21.3) and the search term appeared as ‘exp Drug Interactions/’, recording the fact that we used the explode function.

Step 3: The next step is to combine Searches 1 and 2 to find just those references which have been assigned both ‘Nicotine’ and ‘Drug Interactions’ as subject headings. This can be achieved either by ticking the boxes to the left of Searches 1 and 2 (Figure 21.3) and clicking ‘Combine selections with And’ or by typing ‘1 and 2’ into the search box and hitting return. This gave us 915 hits, drastically reducing the initial figure (Search 3, Figure 21.3).

Step 4: We particularly wished to locate articles published in English and with a human focus, and so we used the limits function to refine Search 3 further, reducing our results to 211 (Search 4, Figure 21.3).

Step 5: We decided that we wanted to isolate references that had nicotine as a main focus. After an initial search for a subject heading, ‘Focus’ can be applied by typing the search number preceded by an asterisk, and combining it with any other search if you wish; we typed ‘*1 and 4’, ensuring that the 143 results in Search 5 (Figure 21.3) only include references where nicotine is a main focus of the research. Note that although we typed ‘*1 and 4’, the Search History records it as ‘*Nicotine/and 4’. Examination of the results revealed a satisfactory scope of articles for use in our review, but Focus should be used carefully as it may result in relevant references being omitted.

In a five-step process, we have identified a range of literature pertinent to our requested review topic.

Advanced Search Using Keywords

MEDLINE® also offers the keyword search method—turn the ‘Map Term to Subject Heading’ feature off, and simply type in words or phrases describing the concepts you wish to search for. You can use ‘AND’ or ‘OR’ directly in the search box, or use the ‘Combine’ feature to add different searches together. It is often recommended that keyword searching and subject heading searching be used together, to ensure fuller retrieval of relevant references, as each method may find references not found by the other.

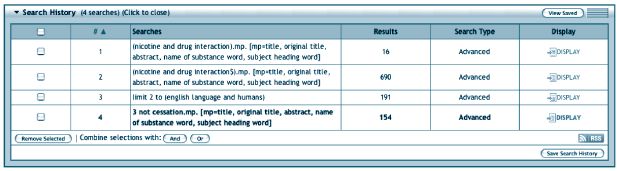

Step 1: Before starting a keyword search, it is best to turn off the mapping function by clicking in the ‘Map Term To Subject Heading’ box to remove the tick. We then immediately used our identified keywords ‘nicotine’ and ‘drug interaction’ typed into the search box linked by the Boolean operator ‘AND’. This input triggers the database to search for articles with both of these keywords appearing in the title, abstract, keywords or subject heading words. Surprisingly, the search only returned 16 results (Search 1, Figure 21.5). A closer look at the search terms revealed why so few articles were found. We knew from our subject heading search that the plural ‘Drug interactions’ was the subject heading and a little thought would lead to the realisation that some authors may use the plural ‘drug interactions’ in titles and abstracts rather than the singular. When searching with keywords the database looks for exactly what you type—in this case, only the singular.

Step 2: We repeated the search and now used the ‘$’ sign to search for truncations. Thus, ‘drug interaction$’ will find both singular and plural. This resulted in a more respectable 690 results (Search 2, Figure 21.5).

Step 3: By limiting to English and human, results were pared down to 191 (Search 3, Figure 21.5).

Step 4: In order to exclude those articles that related to smoking cessation, we limited Search 3 using the Boolean operator ‘not’ to exclude those articles which included ‘cessation’ as a word in title, abstract, etc. (Search 4, Figure 21.5), returning a total of 154 results.

The differing numbers of results between our three searches of the same database illustrate an important point: when you wish to ensure high recall on a topic, it is important to use more than one search method. These three search strategies will have a group of references in common, but each is likely to have retrieved at least some relevant references that were not found by the other strategies. Also remember that there are many more features of MEDLINE® searching (too numerous to list here) including ‘Multi-Field Search’, a new search type introduced in 2008 which allows you to type words or phrases into separate boxes, then make selections as to which fields to search and which Boolean operators to use.

Comparison with a Second Database

As mentioned previously, MEDLINE® and PubMed include essentially the same references, but have completely different search interfaces, which may result in some different references being found. The following brief search illustrates some basic techniques for PubMed searching, but it is by no means exhaustive. Make use of PubMed’s extensive ‘Help’ section to extend your knowledge.

PubMed automatically opens at a search screen inviting you to enter one or more search terms (Figure 21.6). When you do so, the system works to search for both keywords and MeSH subject headings at the same time. This often produces good results on the first search, at other times you may need to try some different approaches, as illustrated by our search.

Step 1: The input ‘nicotine and drug interaction’ produced 1,892 results (Search 1, Figure 21.7). This was far in excess of a similar input into MEDLINE® shown earlier and so was treated with caution. The ‘Details’ tab allows you to see how PubMed has treated your search; inspection revealed that while relevant phrases and MeSH headings had been searched for, PubMed had also searched separately for the words ‘drug’ and ‘interaction’ (or ‘interactions’)—both words had to be present, but not necessarily as a phrase. This is likely to have retrieved too many irrelevant references.

Step 2: We re-ran the initial search but this time truncated ‘drug interaction’ to ‘drug interaction*’. Notice that in PubMed the truncation symbol is different from the one in MEDLINE®. This produced 718 results. Inspection of the ‘Details’ showed that inclusion of the truncation symbol had not only ensured that both singular and plural forms were included, but also that the words drug and interaction(s) had to be bound together as a phrase.

Step 3: Limiting the search to English language articles and human studies reduced the number of articles retrieved to 197 (Search 3, Figure 21.7).

Step 4: Omitting those articles pertaining to cessation of smoking further reduced the number to a final total of 156 (Search 4, Figure 21.7).

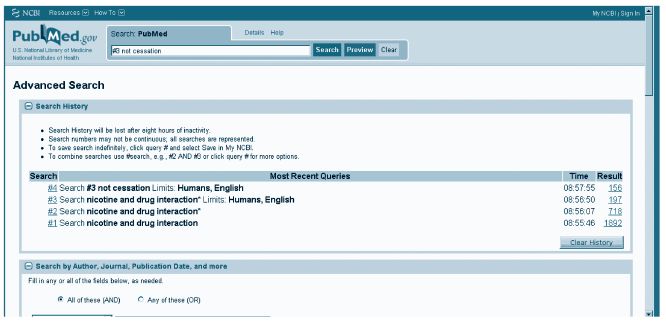

Advanced Features of PubMed

PubMed now offers a link to an ‘Advanced Search (beta)’, which resembles the ‘find citation’ feature in MEDLINE® (Figure 21.7). For more detailed searches, the authors recommend that the user utilises the features displayed on the left-hand side of the PubMed window. As in MEDLINE®, PubMed offers the option to use only MeSH subject headings in your search (click on the MeSH database link), allowing you to take advantage of including relevant narrower terms found in the Tree, applying Focus, etc. Also, you can build up your search in several steps (similar to the technique shown for MEDLINE®), then combine individual search numbers by going to the History tab and typing search numbers combined with Boolean operators. Search numbers must be preceded by ‘#’—for example ‘#3’ and ‘#4’. There are many other features which we recommend that users become familiarised with, including two which the authors find particularly useful—‘Clinical Queries’ and ‘Find Systematic Reviews’. ‘Clinical Queries’ allows the user to search for citations that correspond to specific clinical study categories such as aetiology, diagnosis, therapy, prognosis and clinical prediction guides. These searches may be broad and sensitive, or narrow and specific, depending on the user’s requirements. Within the same ‘Clinical Queries’ window the ‘Find Systematic Reviews’ function allows users to search for comprehensive reviews such as systematic reviews, meta-analyses, reviews of clinical trials, evidence-based medicine and others.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree