Chapter Six. Fertility control

Introduction

Throughout women’s lives, from puberty to the menopause, fertility control is of prime concern. Young women who are sexually active may well become pregnant on their first sexual encounter and should take precautions against pregnancy. The human species is not as fertile as some mammals. A fecundity rate of 20% has been quoted (Evers 2002); i.e. there is a 1:5 chance of conceiving at the most fertile time.

At birth, the female ovary contains immature ova which remain in limbo until puberty. Under hormonal influence one ovum matures at each ovarian cycle. If more follicles ripen in a cycle, the potential of several ova is lost as partially ripened follicles, including their ova, die. Men produce an almost infinite supply of spermatozoa continuously. Few men take control of their own fertility but should do so as this would help prevent unwanted pregnancies. Reproduction and contraception constitute a significant health issue.

World population

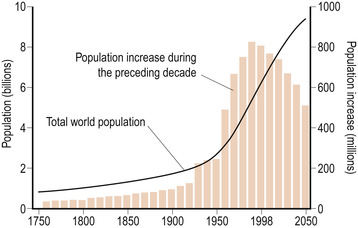

The rate of fertility and the steady rise in world population throughout the 1950s to the 1990s (Fig. 6.1) are directly related to health, environment and poverty. The development of many medical interventions and the greater prosperity of the developed countries have brought about a lower death rate. The trend to have 2.9 children instead of the 6.9 in the 1950s with the lowering death rate has meant that we have an ageing population in Western society with a growth rate declining to 0.1%, whereas population growth in many underdeveloped countries is currently 97% (Nash & De Souza 2002). Despite the graph in Figure 6.1 showing a decline in population in the 21st century, this is misleading and the world population is still expected to increase. It is difficult to predict trends in this area as infertility is increasing and must be compared to the fertility rate at that time (Speidel 2000). Many of the world’s population are young and have still to have their families and there is concern that, unless something can be done to slow down this increase in humanity, famine, infections and wars may intervene.

|

| Figure 6.1 The rate of fertility and rise in world population related to health, environment and poverty. |

Contraception worldwide

Worldwide, the contraceptive effect of breastfeeding probably has as much impact as all the other forms of contraception put together. However, as education increases in under-developed countries, so also will the use of contraception. In the year 2030 it is estimated that 60% of the world’s population will live in urban communities. This will mean environmental change, population change and planning for resources. In the UK, 76% of women use some form of contraception (Table 6.1), the most common being the pill and their partner’s use of the male condom (Agius & Brincat 2006, Family Planning Association (FPA) 2007).

| Sterilisation | Male: 17.0% |

| Female: 13.0% | |

| Pill | 22% |

| Injectable implants | 3.0% |

| Intrauterine device | 6.0% |

| Condom | 18.0% |

| Vaginal barrier | 1.0% |

| Other | 1.0% |

| Rhythm | 1.0% |

| Withdrawal | 4.0% |

The effectiveness of contraception

Contraception has been an issue ever since the link was made between sexual behaviour and pregnancy. It certainly occupied the minds of the ancient Egyptians, Greeks and Romans. In modern times contraception has been openly discussed, used and become legal in most countries only during the last 50 years. There are religious, moral and cultural issues to be considered and therefore it is unlikely that one method will ever become universal.

The ideal contraceptive would be 100% effective, painless, easy to use independently of the user’s memory, cheap and accessible and without medical control. It would also need to be safe; life-threatening problems from pregnancy should be measured against the safety of any contraception used.

Calculating effectiveness

A mathematical concept used to assess the effectiveness of contraceptive methods is the failure rate per hundred woman years (HWY), i.e. the number of pregnancies if 100 women were to use the method for 1 year (Table 6.2); it is also known as the Pearl Index (Guillebaud 2005). In a perfect world this would be truly representative of a method’s effectiveness, but it is complicated by factors such as changes in fertility with age, motivation to use the method correctly every time and the infertility of about 10% who will not know it at the time they are using contraception. It is difficult to differentiate between failure of the method and failure of the user to comply with instructions. Failure often occurs in the early months following commencement of any method; developing skills in using the method make it more reliable.

| The variations in numbers indicate the commitment and skill with which the method is used. | |

| Method | Failure rate per HWY |

|---|---|

| The combined oestrogen with progestogen pill | 0.1–7 |

| The progestogen-only pill | 0.5–7 |

| Injectable progestogen | 0–1 |

| Female barrier methods | 2–15 |

| The male condom | 2–15 |

| The female condom | Not yet known |

| The intrauterine device | 0.3–4 |

| Spermicidal preparations (used alone) | 14–25 |

| Symptothermal method (temperature + cervical mucus) | 1–4 |

| Coitus interruptus | 25 |

| Male sterilisation | 0–0.2 |

| Female sterilisation | 0–0.2 |

Physiological application of contraception

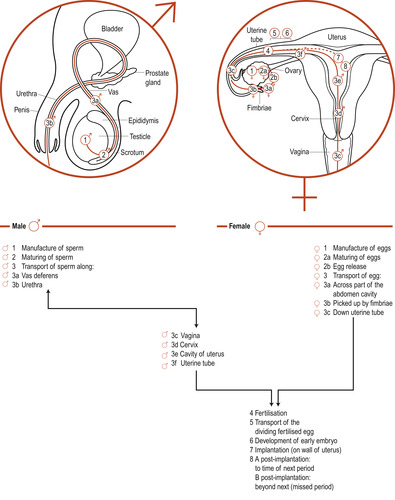

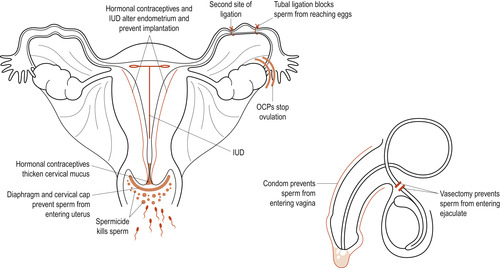

The stages of reproduction of male and female gametes (Fig. 6.2) offer choices of sites for the development of effective methods of contraception (Fig. 6.3).

|

| Figure 6.2 The stages of reproduction. |

|

| Figure 6.3 Mechanisms by which contraceptives work. |

Prevention of gamete production: ovum

Combined oral contraception (COC)

All the ova available to the woman for reproduction are already present in her ovary at birth. Therefore it is not a matter of preventing ovum production but of preventing their maturation and ovulation by suppressing follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinising hormone (LH) at the pituitary level. This, in turn, will prevent the feedback mechanisms between the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland (Coad & Dunstall 2001).

The concept of hormonal control of fertility began in the late 1940s when it was realised that the roots of the wild Mexican yam contained a chemical from which steroid hormones could be produced. Unfortunately, natural hormones are expensive to produce and when taken orally are inactivated by the digestive processes. The word combined is used because the preparations include oestrogens and progestogens. The synthetic oestrogen is ethinylestradiol. The synthetic progestogens used are various and include norethisterone, levonorgestrel and gestodene.

The oestrogen component inhibits FSH release and stops the maturation of the follicle, whereas the progestogen inhibits the release of LH, preventing ovulation. The dose of oestrogen amongst all preparations is a maximum of 20–40 μg. The dose of progestogen is more variable and adds to the contraceptive effect by causing thickening of the cervical mucus (Billings et al 1972) and thinning of the endometrium, making it unsuitable for implantation and reducing the motility of the uterine tubes (Coad & Dunstall 2001).

Since the COC became available in the 1960s it has been beset by media scares, and there is some research evidence to suggest that the higher-dose pills created thrombotic problems in some women. Studies published in 1968 showed a link between the use of COCs and thrombosis. This was thought to be due to the high level of ethinylestradiol in the early pills. However, it has since been realised that a family history of thrombosis or an anticlotting disorder, obesity and cigarette smoking greatly increase the risk of thromboembolism in pill users.

A follow-up of 23 000 women, which included women on the higher-dose pills, found no excessive deaths over a 10-year period. There appeared to be an 80% reduction in ovarian cancer and a 30% reduction in hip fracture at age 75 years when the pill was taken into their forties. Venous thrombosis occurred in 2:100 000 woman years of usage (Kubba et al 2000).

Benefits of the combined pill

• Couples with sexual difficulties because of a fear of pregnancy are relieved of that fear and are able to relax and enjoy a better sex life.

• The pill can be used to combat irregular, painful or heavy periods, preventing anaemia.

• Permits men natural coitus without the use of a condom, preventing erectile problems.

• The combined pill may offer protection against ovarian cancer, possibly due to the cessation of ovulation and quiescence of the ovary. A similar protection against cancer of the endometrium has been noticed.

• The pill protects against some forms of pelvic infection by altering cervical mucus and, because it prevents ovulation and tubal infection (salpingitis), it reduces the risk of ectopic pregnancy (British National Formulary (BNF) 2007).

Complications of the combined pill

• Thromboembolism—Women who take first- and second-generation pills are at a lower risk of thromboembolism (VTE) than are those taking third-generation pills which contain desogestrel and gestoden. Those containing levonorgestrel or norethisterone, the first- and second-generation pills, are those of first choice (RCOG 2004). There is a three-fold risk of VTE when taking COCs which increases with age. The risk increases further if women suffer from a genetic clotting disorder such as factor V Leiden, a quite common variant of clotting cascade factor V, protein C or protein S deficiency (Kujovich 2007). Acquired risk factors such as pregnancy, surgery, immobilisation and malignancy also increase the risk of VTE (RCOG 2004). Some of the side effects occur because the altered physiology of taking the combined pill mimics that of pregnancy. The risk of arterial or venous thrombosis occurs because of increased clotting factors, platelet aggregation and increased serum lipids. The risk is probably low in slim women under 35 who are normotensive, do not smoke and have no personal or familial history of thrombosis. Women who smoke and are obese are at increased risk of cardiovascular disease and VTE, respectively (WHO 2008). Less serious complications such as weight gain, headaches, water retention and increased blood pressure have been reported.

• Cancer—Research indicates that women taking the pill have a reduced incidence of ovarian and endometrial cancer, but women taking oral contraceptives lose the protection that barrier methods give to the cervix. Therefore there is a slightly increased risk of cervical, breast and liver cancer (WHO 2008). While there may have been an increase in breast cancer since the 1960s which may be related to taking oestrogenic compounds, it is possibly due to earlier diagnosis, postponement of the first pregnancy and increased fat consumption, all known risk factors for breast cancer. However, the World Health Organization (WHO 2008) has found a link between women taking the COC and cervical cancer linked to women carrying the human papillomavirus (HPV): 99% of women diagnosed with cancer of the cervix are HPV-positive and one-third are in their twenties (Dyer 2002, Moodley 2004).

• Hypertension—The risk increases with age and is more likely in those who smoke.

• Migraine—Some women find their migraines improve while they take the pill and some find there is deterioration. However, it is serious if women experience focal migraine with transient weakness, numbness of part of the body or loss of part of the visual field, symptoms which may indicate reduced blood flow to the brain; this is classified as WHO group 4 (see p. 70).

• Jaundice—The pill is metabolised by the liver and affects liver function. Most women have a change in bile composition, which may lead to the formation of gallstones. This may be due to an acceleration of the problem rather than being the only cause. A few women may develop jaundice and intense itching of the skin and even fewer women may develop liver tumours.

• Effect on pregnancy—Women who have taken the pill may take longer to become pregnant; this would also include the IUCD and injectable contraceptives (Hassan & Killick 2004).

• Effect on lactation—Oestrogen suppresses the hormone prolactin secreted by the anterior pituitary gland. Prolactin acts on the alveoli of the breast to stimulate milk production. The result will be diminished milk production and a shorter duration of lactation (see The progestogen-only pill, p. 70).

• Drug interactions—Synthetic oestrogens taken orally are well absorbed by the intestinal tract. Unlike natural oestrogens which are rapidly broken down by the liver, synthetic compounds take longer to be metabolised and degraded (Rang et al 2007). The combined pill is probably effective up to 36 h. Other medication may interfere with the contraceptive action of the combined pill. Broad-spectrum antibiotics such as fluocloxacillin may impair intestinal absorption, while most anticonvulsant drugs increase liver enzyme production and hasten drug breakdown. Other drugs such as HIV and TB preparations and St John’s wort could affect the pill’s efficiency. Vomiting and diarrhoea may prevent absorption and the pill should be considered non-effective for that cycle. Oestrogens affect the action of antidiabetic medications (BNF 2007).

WHO classification

In order to define safety in various types of women, the WHO (2008) have devised four categories to guide the practitioner in prescribing the contraceptive pill (Burkman et al 2006):

• Group 1: No restriction of use.

• Group 2: More advantages than risk.

• Group 3: Risk outweighs advantages.

• Group 4: Unacceptable health risk.

Examples:

• Age over 40—group 2.

• Breastfeeding and under 6 weeks postpartum—group 4.

• A non-smoker over 35—group 2.

• A smoker over the age of 35 smoking 15 cigarettes per day—group 4.

• Medical conditions can be categorised: for example, hypertension with no related cardiovascular risk would be group 3 or group 4 (WHO 2008).

The pill should be discontinued if a woman experiences leg pain, abdominal pain, breathlessness and, more serious, with blood-stained sputum, a rise in blood pressure, prolonged headaches, loss or partial sight loss or paraesthesia in a part of the body. Allergic reaction could show as jaundice and result ultimately in liver failure. Discontinuation should also occur before major operative surgery due to the risk of thromboembolism and the consequent inactivity following the operation (Guillebaud 2005).

Prevention of gamete production: spermatozoa

Men typically generate 1000 sperm a minute. The hormones involved are hypothalamic gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which controls pituitary production of LH and FSH. LH stimulates the testes to produce testosterone, which together with FSH induces sperm production (see Ch. 5). The process of spermatogenesis is continuous; there is no singular event similar to ovulation. At present, research is focusing on stopping spermatogenesis by reducing feedback mechanisms and the production of GnRH. Altering testosterone levels may well have side effects and there is a fine balance between aggression and sex drive (Guillebaud 2005). Adding a synthetic form of progesterone (progestogen) may allow a lower dose of testosterone to be given without reducing the contraceptive effect. Researchers (Anderson et al 2002) report on the use of implants (Implanon) containing both progestogens and testosterone and, although spermatogenesis was suppressed, this was variable. Guillebaud (2005) suggests that this is the way forward.

Prevention of fertilisation

The progestogen-only pill (POP)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree