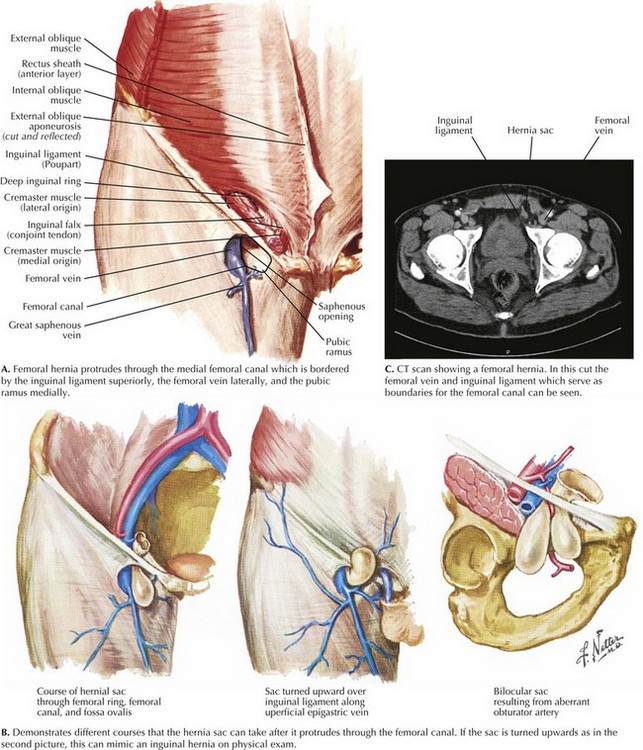

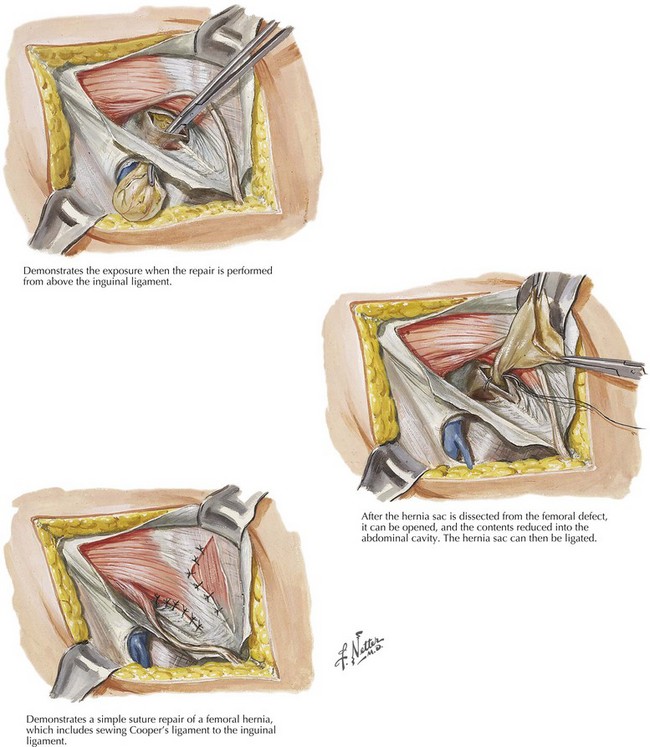

Chapter 30 By definition, the femoral hernia protrudes through the femoral canal, bordered by the inguinal ligament superiorly, the femoral vein laterally, and the pubic ramus inferomedially (Fig. 30-1, A). This space is tight and cannot expand, which leads to the high risk of incarceration and strangulation. The femoral hernia often is seen as an asymptomatic bulge inferior to the inguinal ligament, and as it enlarges, the sac can extend onto the thigh (Fig. 30-1, B). The hernia may or may not be reducible, and patients often report a sensation of fullness. Patients who have incarceration or strangulation often report significant pain, and they may also have evidence of a small bowel obstruction. Additional imaging is not required but can provide useful information, especially when the diagnosis is unclear. Ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) scans can help differentiate between a femoral hernia, inguinal hernia, and inguinal lymphadenopathy (Fig. 30-1, C). If a patient has signs of incarceration or strangulation, urgent repair is warranted. If the diagnosis of a femoral hernia is confirmed preoperatively, the incision can be placed below the inguinal ligament on the upper thigh. If the etiology of the hernia is uncertain, a standard inguinal hernia incision can be made, with plans to divide the transversalis fascia to expose the femoral space. The dissection can be completed from above the inguinal ligament or below (Fig. 30-2).

Femoral Hernia Repair

Anatomy

Clinical Presentation

Imaging

Open Surgical Repair

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine