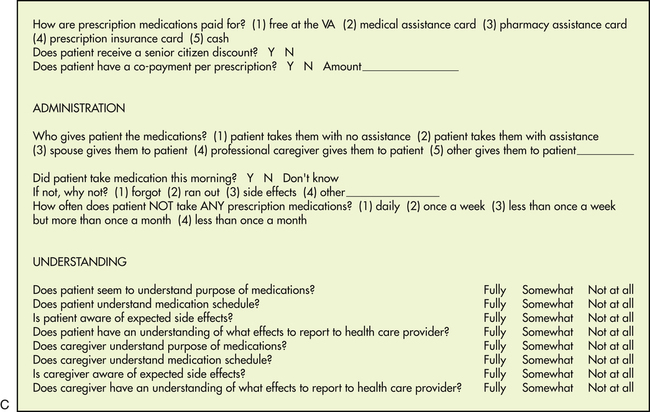

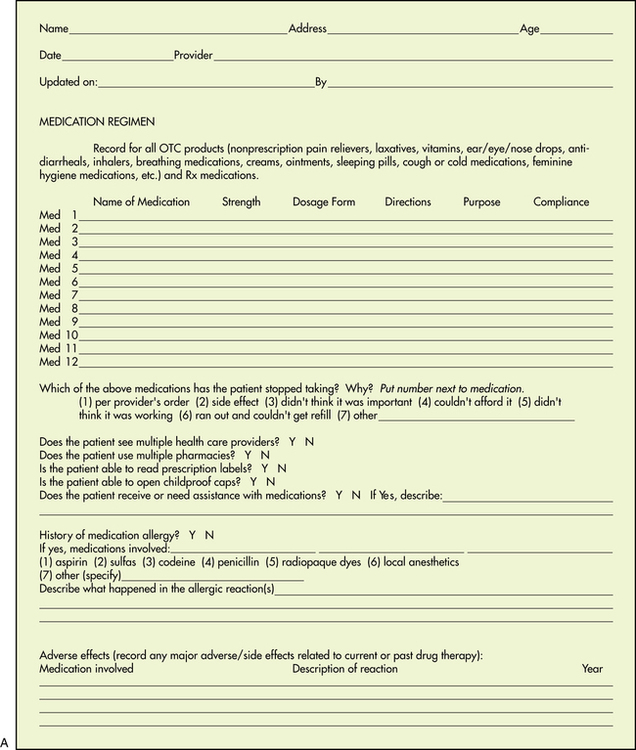

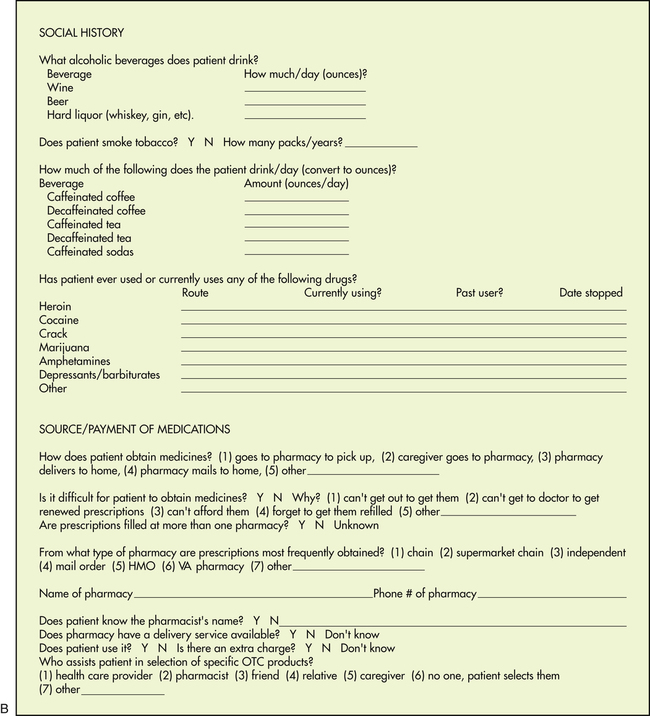

Chapter 9 Up to half of all patients with serious chronic illnesses do not take their medication as prescribed and thus fail to derive the expected benefits (Turnbough & Wilson, 2007). How can this finding be true? Whose responsibility is it when patients fail to comply? What role does the provider play in helping the patient implement the therapeutic regimen or in impeding the process? How can health care providers seek to change this statistic? Reports by researchers (Funnell, 2003; Mitchell & Selmes, 2007) on why patients do not take their medications as instructed concluded the following: • The patient does not understand the seriousness of his or her condition. The issue may be one of vocabulary, denial, or clinician emphasis. • The patient does not understand the instructions. • The patient forgot verbal instructions. • The patient has difficulty taking the medication. • The patient finds a drug (or treatment) regimen too complex. • The patient cannot afford the medicine. • The patient is angry at or depressed about the chronic condition that necessitates the medication. • The patient may have religious or cultural beliefs that prohibit a certain treatment or medication. • The patient may not have transportation to get to the physician’s office or a pharmacy. • The patient may not feel comfortable with the clinician or the medication. • The patient wants attention. The therapeutic experiment is implemented through the relationship established between the health care provider and the patient. This relationship will be therapeutic if it allows the goals of treatment to be met. Therefore, the major task of patient and provider is to establish a long-term relationship so that treatment, including the use of medications, will be implemented appropriately and effectively. It involves a stepwise process—identify a problem, assess it adequately, identify various potential solutions, examine the variables needed to judge the risk-benefit ratio of the solutions, choose the most appropriate solution, and, finally, identify the effects (both beneficial and adverse) that may result from implementation of the chosen solution (see Chapter 11 on making clinical decisions).Several factors are essential to establishing this therapeutic relationship. These include time, attitude, information, communication, and positive feedback. Expert diagnosticians have maintained that the most important part of information gathering is the history. Many formats have been established for collecting needed information about a patient. The open-ended questions of medical and nursing school are almost always abbreviated or reduced to checklists and forms by the experienced clinician in day-to-day clinical practice. It is important to obtain a comprehensive database for patients for whom pharmacologic therapy is anticipated, especially with regard to medications. This type of information often is best obtained by having patients fill out preprinted forms regarding their medication experience. Although it would be ideal to have this information before the first visit with the health care provider, the reality is that a comprehensive history may take several visits to acquire, with the health care provider collecting a little more information with each visit. Using a history-taking form about medications, such as that illustrated in Figure 9-1, helps to standardize the information collected and allows it to be expanded during several succeeding sessions. The information collected should not only be comprehensive but customized to the patient population (e.g., inner city, migrant, elderly) and to the specific problem under evaluation (e.g., cardiovascular, diabetes). If patient medications are to be adequately managed, an updated medication list should be part of every chart (Rooney, 2003) and should be updated routinely with every visit. While some health care providers may not consider it, there is a growing trend among patients to want more access to their medical records. Researchers recently found that 22% of patients want to see and share their medical records, including provider notes, with family members and other medical providers. So health care providers need to clearly think about what they are preserving in the health records and how it reflects on their communication, attitudes, and provision of basic information (Walker et al, 2011). A 2011 survey published in the British medical journal BMJ Quality & Safety showed that 89% of clinicians believed it was important to ask patients about their expectations of care, but only about 16% of them reported that they did so. Clearly, if clinicians do not ask their patients about their expectations, it is going to be difficult to meet them. In this study, nurses were more likely to discuss expectations with patients than physicians were (Rozenblum et al, 2011). A 2011 report calculated the relative risks of mortality for different social factors such as extent of education, poverty, employment status, health insurance status, job stress, presence of social support, racism or discrimination, housing conditions, and early childhood stressors. Prevalence estimates for each social factor were calculated using U.S. Census Bureau data. According to the report, “About 245,000 deaths in the United States in 2000 were attributable to low levels of education, 176,000 to racial segregation, 162,000 to low social support, 133,000 to individual-level poverty, 119,000 to income inequality, and 39,000 to area-level poverty. Altogether, 4.5% of deaths were found to be attributable to poverty, and risks associated with both low education and poverty were higher for individuals age 25-64 than for those 65 or older who qualified for Social Security and Medicare.” The report claimed that the number of deaths calculated as attributable to low education was comparable to the number caused by heart attack, the leading cause of U.S. deaths in 2000. The study concluded that the estimated number of deaths in the United States that were attributable to social factors is comparable to the number attributed to pathophysiologic and behavioral causes. These figures are compelling arguments for a broader public health conceptualization of the causes of mortality and a more expansive approach that considers how social factors should be addressed to improve the health of populations (Galea et al, 2011). Other strategies that have been identified as helpful in establishing a relationship with the patient include the health care provider’s friendliness; a positive, confident approach; a thoughtful response to patient complaints; encouraging patient questions; a supportive, nonjudgmental method of eliciting and responding to patient admissions of noncompliance; and encouraging patients to become actively involved in their own care. Techniques that encourage active patient participation as opposed to provider-dominated decisions, negotiating rather than dictating a treatment plan, and identifying and resolving barriers to compliance are also helpful. Finally, attempting to find congruence between patient and provider in their understanding of a problem and its management and efforts to motivate the patient and increase patient satisfaction are also helpful (Frishman, 2007; Goeman & Douglass, 2007; Swanson, 2003; Wilson et al, 2007). In the classic article by Chessare (1998) on teaching clinical decision making to physicians, the author maintains that after presenting information, the health care provider needs to elicit the patient’s preferences for health and other outcomes. For example, it is not enough to give a family the probability that a child will be left with significant morbidity after a potentially life-sustaining procedure. It is also necessary to have the parents consider what the morbidity may mean to them and their child. This discussion should include information on the child’s somatic and psychologic well-being in the context of family life and the financial repercussions for the family of specific clinical decisions (Chessare, 1998). A prudent course must be charted between creating uncontrolled and unfounded anxieties on the one hand and generating a false sense of equally groundless security and reassurance on the other. Health care providers also have a societal duty to consider the consequences of the decisions both they and the patients make for the greater good of the community. For example, the parents’ decision not to provide immunization for their child because of concerns about adverse reactions places others in the community at risk. When a higher-cost strategy gives no added benefit to the patient, then it is appropriate for the health care provider to use a lower-cost choice. When higher-cost strategies of potential benefit are available, the health care provider must be able to frame decisions for families such that they understand the expected added benefit (Chessare, 1998; Kraetschmer et al, 2006). For example, the family of a patient with tuberculosis might be convinced that it is in the interest of public safety for a judge to put the patient in jail until a supervised course of medication therapy can be concluded rather than allow the patient to remain noncompliant with drug therapy in the community. It is essential for providers to help the patient recognize that other factors, in addition to his own preferences, must be considered in the decision of whether to take medication for a particular problem. Providers also do not have the right to withhold effective therapies chosen by the family simply because they are more costly than others. Because managed care is about providing health care within budget constraints, the pressure to contain costs by limiting care is significant in most plans. This is especially true regarding drug therapy. This pressure is strongest in for-profit plans, where breaking even is not enough. It is now also seen with Medicaid patients, for whom drug choices may be severely limited by formularies for less costly, and sometimes less effective, medications. Ethically, providers must refrain from withholding strategies that are marginally superior to others simply because they are too expensive. This is sometimes difficult given the restrictions of some payment plans, but in some situations, to do otherwise is a violation of the patient–provider relationship (Kraetschmer et al, 2006). If policies of a managed care organization or other organization would preclude the prescription of recommended therapy, the provider must continue to act as the family’s agent and help them obtain the desired care. When the provider cannot support the desires of the patient, he has a duty to make this clear to the patient. If the patient continues to see his desire as appropriate, the provider must assist him in finding another provider (Chessare, 1998; Kraetschmer et al, 2006). The provider’s assessment of the patient’s history and physical and laboratory information will answer the questions “What etiology?” “Why now?” and “How severe?” This step allows for further refinement of the problem and speculation as to the probable causes and potential risk to the patient based on information gathered in the database. “What etiology?” suggests potential treatments of a correctable cause. “Why now?” is particularly important in acute exacerbations of chronic disease or detection of immune deficiencies, for it leads to an approach that treats the acute problem and prevents further difficulty. “How severe?” leads to decisions on the rapidity and perhaps the nature of treatment (see Chapter 11 on making clinical decisions). If the patient agrees to drug therapy, the provider must offer specific explanations about what medication the patient is to take and why (see Chapter 11 on making clinical decisions). The selected modality should be as specific for the problem and the therapeutic objective as possible. Evidence-based medicine will provide direction about what has proved effective. In the absence of definitive recommendations, agents or modalities will be selected on the basis of cost, efficacy, lowest toxicity, and other patient and drug variables. Both patient- and agent-related variables must be considered in the final selection and administration of an agent. Agent-related variables are defined as those properties of any agent that are characteristic of that agent and that affect its use in a given situation. Examples of this would be chemical properties, formulation, absorption, metabolism and excretion, toxicity, half-life, and bioavailability (see Chapter 3 on pharmacokinetics). Detailed instructions must be given to the patient, preferably in writing, about how to take medication (see Chapter 11 on tips in writing prescriptions and Chapter 10 on design and implementation of patient education). One cannot rationally administer an agent without first understanding variables that affect its administration. Patients should understand what they might expect, both positively and negatively, when taking this medication.

Establishing the Therapeutic Relationship

Establishing Therapeutic Relationships in Treatment

Information

Communication

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

/>

/> />

/>