Esophagus and Stomach1

Mark H. Delegge

1Abbreviations: DS, dumping syndrome; ENS, enteric nervous system; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; LES, lower esophageal sphincter; UES, upper esophageal sphincter.

The esophagus and stomach are critical structures involved in the process of oral intake and digestion. Absorption of nutrients in these organs is minimal. Without a properly functioning esophagus and stomach, the ability to eat and initially digest can be significantly impaired. Additionally, partial or total surgical resection of the esophagus or stomach, for symptomatic disease states, also can markedly affect a person’s ability to eat or drink. Physiologic and anatomic aspects of the esophagus and stomach are covered in detail in the chapter on the nutritional physiology of the alimentary tract.

ESOPHAGUS

Anatomy

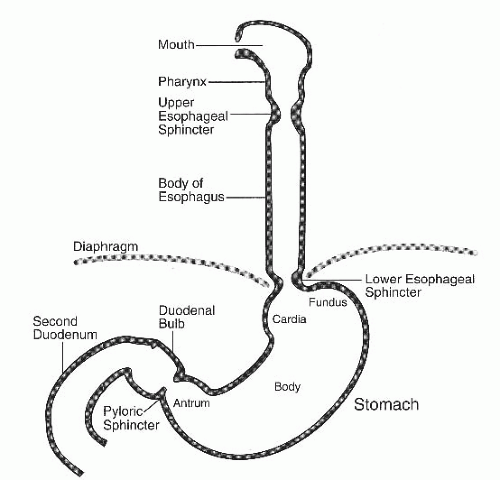

The esophagus is a tubular structure that is approximately 30 cm in length (1) (Fig. 74.1). The organ is artificially divided into the proximal, mid, and distal esophagus. This structure is extremely muscular, which correlates to its major function, propulsion. The funnel-shaped pharynx joins the mouth to the esophagus. Where the pharynx connects to the esophagus is a ring of tissue known as the upper esophageal sphincter (UES). The sphincter opens to allow food or fluids to pass with a swallowing effort. The upper esophagus consists of striated muscle. There is an inner circular layer and an outer longitudinal layer of muscle. At the level of the aortic arch, the esophageal striated muscle transforms into smooth muscle. A ring of thick smooth muscle called the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) sits at the bottom of the esophagus and is approximately 40 cm from the incisors (teeth). The LES serves to allow food and fluids to flow from the esophagus when it is in a relaxed state and to prevent regurgitation of gastric materials back into the esophagus when it is in a contracted state. The muscle of the esophagus receives its innervation from cranial nerve X (2). This nerve originates in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve and synapses on the myenteric plexus (esophageal nerve system).

Disease

When disease of the esophagus exists, it generally involves a process that affects the esophageal lining (mucosa) or the muscular component of the esophagus.

Muscular (Motor)

The classic muscle disorder of the esophagus is known as achalasia (3). The primary features are lack of esophageal muscle contractions (peristalsis) in combination with failure to relax the LES. This leads to the inability of materials to flow from the mouth through the esophagus and into the stomach. If a diagnostic radiogram is obtained, it will show a dilated esophagus and a tight LES resulting in what radiologist’s term a classic “bird’s beak” sign. Interestingly, these patients have a 2% to 7% risk of squamous cell cancer of the esophagus. Treatment consists of medications (very poor results) or the use of a large balloon or surgery to tear the LES. This treatment attempts to eliminate the LES barrier to food and fluid movement through the esophagus to the stomach. Because of their poor esophageal propulsion, these patients are very dependent on gravity and must remain upright after eating to allow materials to pass from the mouth to the stomach. These patients can regurgitate food back into their mouth with the risk for aspiration, especially at night when they are lying down. In some cases, patients are unable to consume enough calories and protein by mouth and require a gastrostomy tube for enteral nutrition, assuming their stomach functions appropriately.

Hypomotility (decreased muscle contractions) of the esophagus can occur with systemic disease in which the muscle and/or nerves of the esophagus are affected, resulting in reduced or absent peristalsis (4). This occurs

commonly in scleroderma and other connective tissue diseases. Other diseases that can lead to hypomotility disorders of the esophagus include diabetes mellitus, amyloidosis, or hypothyroidism. There are no known effective treatments for hypomotility disorder effects on the esophagus. Patients will attempt to modify their diet (more liquids in their diet). Failure to be able to consume enough nutrition orally should result in the placement of a gastrostomy tube for enteral nutrition support. (Please see the chapter on enteral feeding for tube feeding strategies.)

commonly in scleroderma and other connective tissue diseases. Other diseases that can lead to hypomotility disorders of the esophagus include diabetes mellitus, amyloidosis, or hypothyroidism. There are no known effective treatments for hypomotility disorder effects on the esophagus. Patients will attempt to modify their diet (more liquids in their diet). Failure to be able to consume enough nutrition orally should result in the placement of a gastrostomy tube for enteral nutrition support. (Please see the chapter on enteral feeding for tube feeding strategies.)

Inflammation and Cancer

Mucosal-based disease also can affect a person’s ability to eat. The best example of this is cancer of the esophagus. Adenocarcinoma is now the most common cause of esophageal cancer in the United States. Deficiency or low intake of specific nutrients (vitamins A, B6, C, E, and folate) has been epidemiologically associated with esophageal cancer (5). Dietary fiber has been suggested to be protective against the development of adenocarcinoma in such studies. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus is believed to be secondary to chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). This leads to the development of a histologic precursor of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, known as Barrett esophagus (6).

Worldwide, squamous cell cancer of the esophagus is the most common esophageal cancer. It is caused by tobacco and alcohol use most frequently. Other less common associations include achalasia, lack of trace metals (especially selenium), lye ingestion, ionizing radiation, and human papillomavirus. Deficiency of vitamins A and C also is associated with the development of squamous cell cancer of the esophagus. Overall, cancer of the esophagus is more common in men by a 3:1 ratio (7).

In patients with esophageal cancer, oral intake can be compromised because of esophageal obstruction. The tumor itself can be shrunk temporarily with the use of endoscopic therapies, including tumor tissue ablation. The placement of an esophageal stent across the tumor also can temporarily open the esophagus (8). Frequently, the patient cannot eat or drink enough to maintain his or her nutritional status and requires a gastrostomy feeding tube. Some surgeons prefer a jejunostomy feeding tube over a gastrostomy feeding tube for patients who will receive surgery because they do not want a hole in the stomach to repair before pulling it up into the thoracic cavity after esophagectomy (9).

Treatment of esophageal cancer is poor if surgery is not an option for cure. Radiation is rarely used as monotherapy for esophageal cancer. Chemotherapy can be used as monotherapy but is more commonly used as systemic therapy for patients with metastatic disease. Combined radiotherapy and chemotherapy are used for patients with regional metastasis. Esophagectomy is the primary treatment for esophageal cancer and generally is reserved for patients who have an optimal chance of being completely cured (10). Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy entails removal of most of the esophagus and a pull-up of the stomach into the thoracic cavity and the attachment of the esophagus to the very upper portion of the esophagus just below the UES. This surgery carries a 5% to 10% mortality rate. Morbidity from this surgery can include anastomotic leakage, pulmonary problems, and coronary events. Patients can develop anastomotic strictures, gastroparesis, and regurgitation after surgery. This problem can become significant enough to require a feeding tube. In these situations, a jejunal feeding tube is required.

Inflammation and ulceration of the esophagus also can impair oral intake. Generally, this is secondary to the pain of inflammation, but it also can be secondary to the chronic problems seen with esophageal mucosal inflammation, such as esophageal strictures, leading to partial or complete esophageal obstruction.

The definition of GERD is damage to the esophageal mucosa from the regurgitation of gastric contents. Approximately 18% of the US population reports GERD symptoms weekly (11). Increasing age increases the frequency of GERD. Patients with GERD may have impaired quality of life because of intermittent pain and nausea. Although very effective medical treatment strategies for GERD exist, approximately 5% to 10% of patients are recalcitrant to the medications. Corrective surgical therapy may be required for these patients. The most common surgery is a Nissen fundoplication (12).

Anorexia may develop with GERD because chronic discomfort and nausea resulting from reflux can affect appetite. In addition, if the GERD symptoms are worse with eating, this will also result in a reduced oral intake.

It has been shown that GERD can be a cause of anorexia in elderly persons. More severe manifestations of GERD are esophageal ulceration and stricture formation (13). GERD-based strictures are more commonly seen in the distal esophagus. These strictures may require balloon dilation with the use of an endoscope. The “obstruction” caused by these strictures can lead to a change in diet or a markedly reduced oral intake resulting in malnutrition and weight loss.

It has been shown that GERD can be a cause of anorexia in elderly persons. More severe manifestations of GERD are esophageal ulceration and stricture formation (13). GERD-based strictures are more commonly seen in the distal esophagus. These strictures may require balloon dilation with the use of an endoscope. The “obstruction” caused by these strictures can lead to a change in diet or a markedly reduced oral intake resulting in malnutrition and weight loss.

STOMACH

Anatomy

The stomach is a large tubular structure that has the ability to expand significantly to accept both fluids and food (see Fig. 74.1). It is divided into four separate components; the cardia, the fundus, the body, and the antrum (proximal to distal stomach, respectively). Histologically, the muscle cells in the antrum are the densest. At the top of the stomach is the LES described previously. At the bottom of the stomach is another valve, the pylorus, which regulates movement of material from the stomach into the small intestine. The stomach itself, in addition to expanding to accommodate ingested materials, grinds food into smaller particles by the “crushing” action of the antrum.

The stomach wall consists of four layers: the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, and serosa (14). The submucosal layer consists of connective tissue interlaced with the enteric nervous plexus (the nerve system of the stomach). It is known that the origin of electrical activity in the stomach (pacemaker) exists in the body of the stomach at the greater curvature. Digestive events in the stomach are linked to the functional capacity of different cell populations of the gastric epithelial lining. The gastric lining consists of thick folds, each of which contains microscopic gastric pits (14). The mucosa of the body and fundus of the stomach contains oxyntic glands (Fig. 74.2). Oxyntic glands are lined by parietal cells that secrete gastric acid and intrinsic factor and by chief cells that secrete pepsinogen and gastric lipase (14). In contrast, the pyloric glands that form the antral mucosa contain few parietal cells or chief cells, but rather contain mucus-secreting cells and G cells, which produce the hormone gastrin (see Fig. 74.2).

Motor Function (Contraction)

Motor function of the gastrointestinal tract depends on the contraction of smooth muscle cells and integration and modulation by enteric and extrinsic nerves. Derangements of the mechanisms that regulate gastrointestinal motor function may lead to altered gut motility. The nervous system controlling gastric motility includes both the central nervous system and the enteric nervous system (ENS) (15). The ENS is the gut’s intrinsic neural system. It consists of approximately 100 million neurons organized into ganglionic plexuses.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree