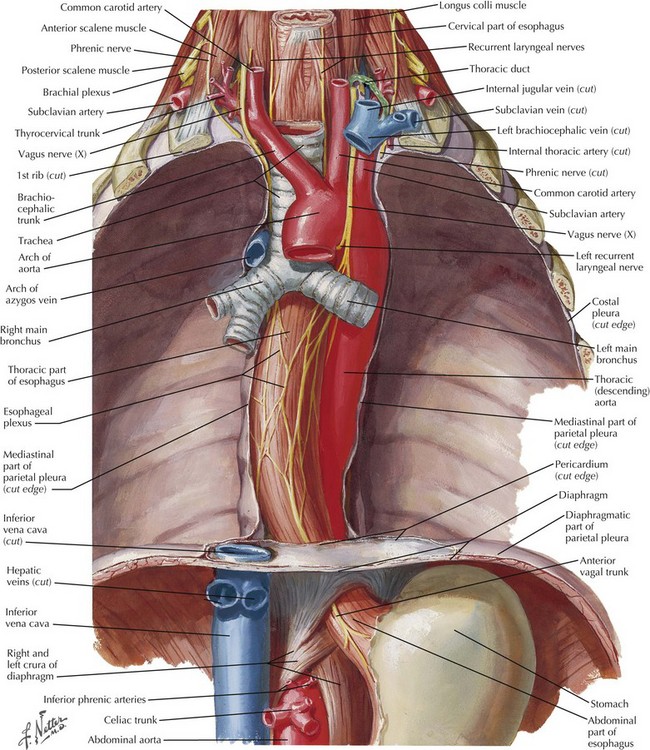

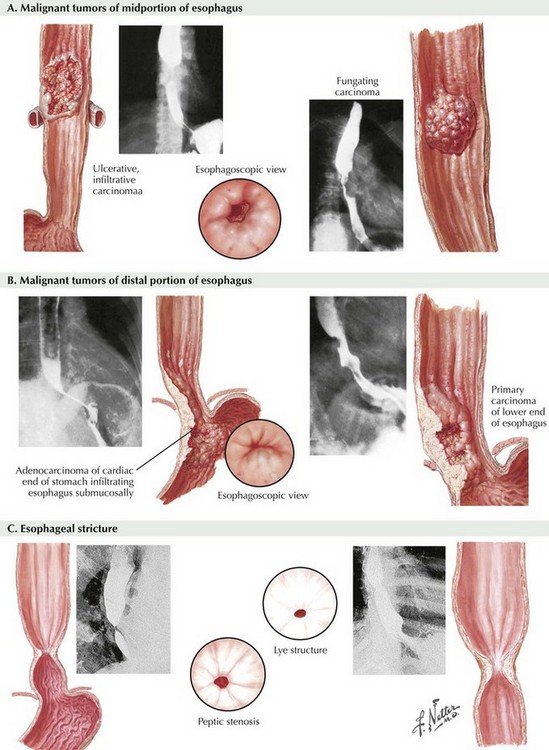

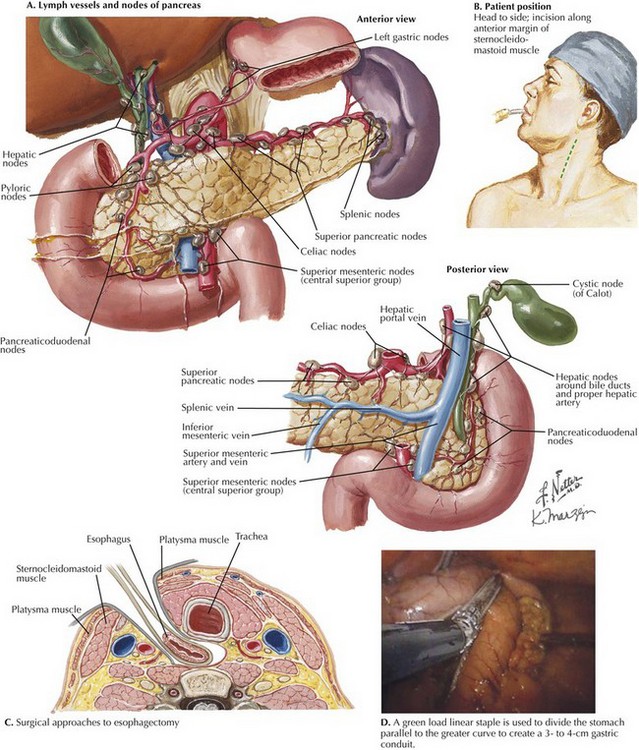

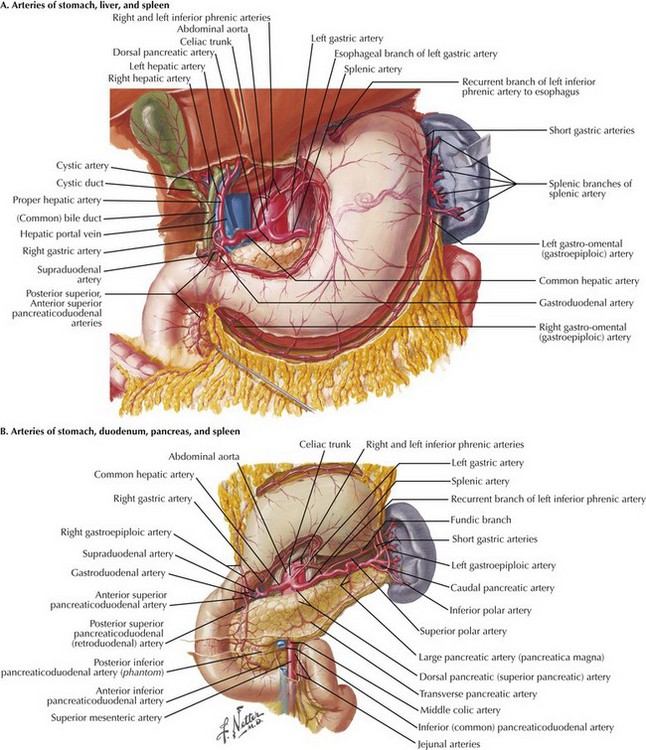

Chapter 5 Franz Torek performed the first successful esophagectomy in 1913, after this high-risk surgery had been described 30 years with no patient survivors. Improvements in technique and patient care have reduced the mortality and morbidity, but esophagectomy remains one of the most dangerous surgeries performed, with a mortality rate of 4% to 10% and a complication rate of 20% to 60%. This dramatic risk profile results from (1) difficult anatomic position of the esophagus (Fig. 5-1), (2) involvement of three body cavities in the resection, (3) tenuous blood supply of all reconstruction options, and (4) nutrition impact on the surgical patient. Because of the associated morbidity, most esophagectomies are performed on cancer patients (Fig. 5-2, A and B). Benign indications arise from absolute loss of function caused by end-stage motility disorders or from refractory strictures (Fig. 5-2, C). Worldwide, the primary esophageal cancer is squamous cell type, the result of dietary insults or smoking. In North America, however, this is no longer true: 80% or more of esophageal cancers are now adenocarcinomas related to gastroesophageal reflux and Barrett syndrome (metaplasia). The transhiatal esophagectomy is performed with the patient supine and the left side of the neck prepped and exposed. Either an upper midline incision or, increasingly, a five-port laparoscopic access is performed. Exploration is performed to rule out disseminated tumor, which would obviate resection in most cases. The greater curvature of the stomach is retracted anteriorly, and the gastrocolic omentum is divided from the spleen to the hepatic flexure, wide of the gastroepiploic blood supply, which is critical for the viability of the gastric graft (Fig. 5-3, A). Once the greater curvature is fully mobilized, the retrogastric adhesions to the peritoneum are divided. The lesser curvature of the stomach is then mobilized, a Kocher maneuver is performed to mobilize the duodenum, and the gastrohepatic ligament is divided near its attachment to the liver (Fig. 5-3, B). This exposes the D1 node area, which is routinely dissected. FIGURE 5–3 Anatomy of the lesser curve, second portion of the duodenum, and gastrohepatic ligament (stomach is rotated cephalad). Node dissection margins include the porta hepatis (hepatic portal) structures, the hepatic artery, and the vena cava (Fig. 5-4, A). Dense nodal tissue around the base of the left gastric artery is dissected, and the coronary vein and left gastric artery are divided with an energy sealing device, stapler, or suture ligation. Node tissue is left in continuity with the specimen. The hiatus is typically opened by excising a rim of the hiatal musculature and entering the mediastinum in the plane of the mediastinal pleura, pericardium, and preaortic and prespinal planes. This maneuver is more feasible with a laparoscopic approach and allows good lymphatic clearance of the lower mediastinum.

Esophagectomy

Introduction

Indications

Transhiatal Esophagectomy

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine