High-Yield Terms to Learn

Athetosis Involuntary slow writhing movements, especially severe in the hands; “mobile spasm” Chorea Irregular, unpredictable, involuntary muscle jerks that impair voluntary activity Dystonia Prolonged muscle contractions with twisting and repetitive movements or abnormal posture; may occur in the form of rhythmic jerks Huntingdon’s disease An inherited adult-onset neurologic disease characterized by dementia and bizarre involuntary movements Parkinsonism A progressive neurologic disease characterized by shufflinq gait, stooped posture, resting tremor, speech impediments, movement difficulties, and an eventual slowing of mental processes and dementia Tics Sudden coordinated abnormal movements, usually repetitive, especially about the face and head Tourette’s syndrome A neurologic disease of unknown cause that presents with multiple tics associated with snorting, sniffing, and involuntary vocalizations (often obscene) Wilson’s disease An inherited (autosomal recessive) disorder of copper accumulation in liver, brain, kidneys, and eyes; symptoms include jaundice, vomiting, tremors, muscle weakness, stiff movements, liver failure, and dementia

Parkinsonism

Pathophysiology

Parkinsonism (paralysis agitans) is a common movement disorder that involves dysfunction in the basal ganglia and associated brain structures. Signs include rigidity of skeletal muscles, akinesia (or bradykinesia), flat facies, and tremor at rest (mnemonic RAFT).

Naturally Occurring Parkinsonism

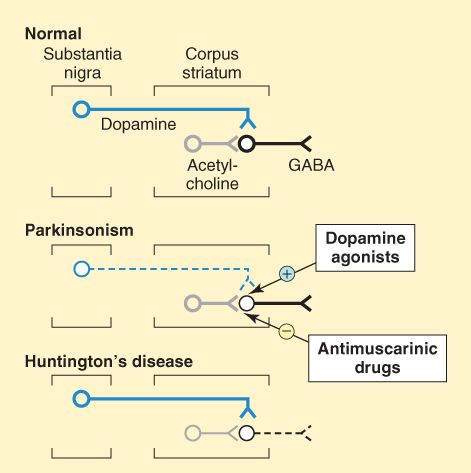

The naturally occurring disease is of uncertain origin and occurs with increasing frequency during aging from the fifth or sixth decade of life onward. Pathologic characteristics include a decrease in the levels of striatal dopamine and the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the nigrostriatal tract that normally inhibit the activity of striatal GABAergic neurons (Figure 28-1). Most of the postsynaptic dopamine receptors on GABAergic neurons are of the D2 subclass (negatively coupled to adenylyl cyclase). The reduction of normal dopaminergic neurotransmission leads to excessive excitatory actions of cholinergic neurons on striatal GABAergic neurons; thus, dopamine and acetylcholine activities are out of balance in parkinsonism (Figure 28-1).

FIGURE 28-1

Schematic representation of the sequence of neurons involved in parkinsonism and Huntington’s chorea. Top: Neurons in the normal brain. Middle: Neurons in parkinsonism. The dopaminergic neuron is lost. Bottom: Neurons in Huntington’s disease. The GABAergic neuron is lost.

(Reproduced, with permission, from Katzung BG, editor: Basic & Clinical Pharmacology, 9th ed. McGraw-Hill, 2004: Fig. 28-1.)

Drug-Induced Parkinsonism

Many drugs can cause parkinsonian symptoms; these effects are usually reversible. The most important drugs are the butyrophenone and phenothiazine antipsychotic drugs, which block brain dopamine receptors. At high doses, reserpine causes similar symptoms, presumably by depleting brain dopamine. MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine), a by-product of the attempted synthesis of an illicit meperidine analog, causes irreversible parkinsonism through destruction of dopaminergic neurons in the nigrostriatal tract. Treatment with type B monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) protects against MPTP neurotoxicity in animals.

Drug Therapy of Parkinsonism

Strategies of drug treatment of parkinsonism involve increasing dopamine activity in the brain, decreasing muscarinic cholinergic activity in the brain, or both.

Although several dopamine receptor subtypes are present in the substantia nigra, the benefits of most antiparkinson drugs appear to depend on activation of the D2 receptor subtype.

Levodopa

Mechanisms

Because dopamine has low bioavailability and does not readily cross the blood-brain barrier, its precursor, L-dopa (levodopa), is used. This amino acid enters the brain via an L-amino acid transporter (LAT) and is converted to dopamine by the enzyme aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (dopa decarboxylase), which is present in many body tissues, including the brain. Levodopa is usually given with carbidopa, a drug that does not cross the blood-brain barrier but inhibits dopa decarboxylase in peripheral tissues (Figure 28-2). With this combination, the plasma half-life is prolonged, lower doses of levodopa are effective, and there are fewer peripheral side effects.

FIGURE 28-2

Pharmacologic strategies for dopaminergic therapy of Parkinson’s disease. The actions of the drugs are described in the text. MAO, monoamine oxidase; COMT, catechol-O-methyltransferase; DOPAC, dihydroxyphenylacetic acid; L-DOPA, levodopa; 3-OMD, 3-O-methyldopa.

(Reproduced, with permission, from Katzung BG, editor: Basic & Clinical Pharmacology, 11th ed. McGraw-Hill, 2009: Fig. 28-5.)

Pharmacologic Effects

Levodopa ameliorates the signs of parkinsonism, particularly bradykinesia; moreover, the mortality rate is decreased. However, the drug does not cure parkinsonism, and responsiveness fluctuates and gradually decreases with time, which may reflect progression of the disease. Clinical response fluctuations may, in some cases, be related to the timing of levodopa dosing. In other cases, unrelated to dosing, off-periods of akinesia may alternate over a few hours with on-periods of improved mobility but often with dyskinesias (on-off phenomena). In some case, off-periods may respond to apomorphine. Although drug holidays sometimes reduce toxic effects, they rarely affect response fluctuations. However, catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitors used adjunctively may improve fluctuations in levodopa responses in some patients (see below).

Toxicity

Most adverse effects are dose dependent. Gastrointestinal effects include anorexia, nausea, and emesis and can be reduced by taking the drug in divided doses. Tolerance to the emetic action of levodopa usually occurs after several months.

Postural hypotension is common, especially in the early stage of treatment. Other cardiac effects include tachycardia, asystole, and cardiac arrhythmias (rare).

Dyskinesias occur in up to 80% of patients, with choreoathetosis of the face and distal extremities occurring most often. Some patients may exhibit chorea, ballismus, myoclonus, tics, and tremor.

Behavioral effects may include anxiety, agitation, confusion, delusions, hallucinations, and depression. Levodopa is contraindicated in patients with a history of psychosis.

Dopamine Agonists

Bromocriptine

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree