113

CHAPTER OUTLINE

The tide is slowly turning away from incarceration of offenders in jails or prisons in the United States. For example, there was a 1.3% decline in the number of imprisoned offenders in 2010 (1). However, almost 2.3 million persons remain incarcerated in the United States, while another 7.1 million are on probation or parole (2). This amounts to one in every 33 adults in the country.

The link between criminal activity and alcohol and other drug use is clear. In a 2011 study of arrestees, 60% tested positive for one or more drugs (other than alcohol) within 48 hours of apprehension. At all but one test site, almost 80% of arrestees had been arrested previously, and many had been arrested more than once in the preceding 12 months (3).

Over the past two decades, it has become abundantly clear that incarceration alone is totally ineffective in addressing alcohol and other drug abuse and addiction. It also does not reduce recidivism rates. Society is coming to realize that prison is a scarce resource best employed to isolate violent offenders from the community. Such a change in philosophy, coupled with an increased knowledge of the neurobiology of addiction and its treatment, has led to an understanding by the community and the criminal justice system that collaborative approaches such as drug treatment courts (DTCs) are the most intelligent way to address this issue.

A DTC is a collaborative program of judicially supervised treatment and recovery within the criminal justice system. This specialized system of courts was created to address spiraling numbers of drug-related offenses and offenders, which have swelled court dockets over the past two decades. DTCs represent a major retooling of the criminal justice system as well as a new role for the courts as an interdisciplinary, problem-solving community institution with therapeutic implications—in short, a partner in public health (4).

From fewer than a dozen in 1991, the number of DTCs has increased to more than 2,600 today, in communities as diverse as New York City and Las Cruces, New Mexico. DTCs are found in all states, all federal district and tribal courts (called Healing to Wellness Courts), and in 20 countries.

This chapter examines the theoretical underpinnings of DTCs and explains how they differ from traditional criminal courts. Treatment opportunities in the criminal justice system are explored, as are the key components of effective DTCs. The chapter focuses on the role of these courts within the treatment community and describes opportunities for collaboration between the court system and the health care community, particularly addiction specialists.

DEFINITIONS

A DTC is a judicially supervised, treatment-driven program for high-risk, high-need criminal offenders who have substance use disorders. It is a collaborative effort that involves judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys, probation officers, law enforcement, treatment providers, and other persons or agencies that interact with substance-dependent individuals whose behavior has brought them into the criminal justice system. Participation by the offender is voluntary in that involvement with the DTC is a condition of diversion, probation, or parole (Table 113-1).

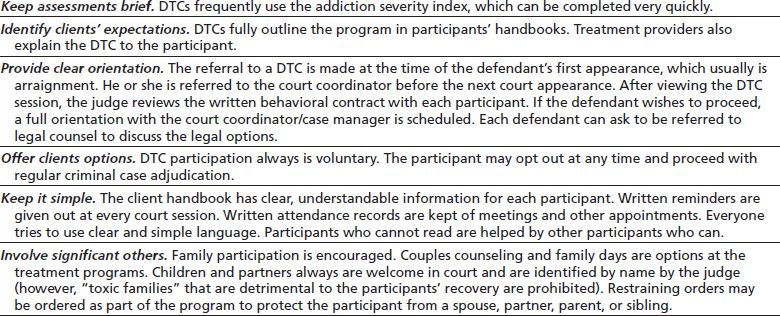

TABLE 113-1 ADVICE ON INITIATING TREATMENT WITH DRUG COURT CLIENTS

DTC, drug treatment court.

The court serves as a convener and coordinator of services in a continuum of care for individuals with substance use disorders.

DTCs are as varied in form and format as the diverse legal and treatment cultures from which they spring. Some courts divert offenders from the criminal justice system entirely, while others accept only misdemeanants and yet others only felons. There are DTCs solely for alcoholics or cocaine or heroin users, whereas other DTCs accept anyone whose criminal involvement is related to substance use. There are courts that focus on those who drive while impaired or serial inebriants with arrest records dating back decades. There are gender- specific courts and courts that enroll only juveniles. Reentry DTCs serve adjudicated offenders with substance use disorders who are returning to society on parole or probation. Recently, veterans’ courts have emerged for returning warriors, many of whom have substance use disorders and co-occurring mental health issues such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and physical problems such as traumatic brain injury.

DTCs rely on the principle that the coercive powers of the court system can contribute to recovery from addiction to alcohol and other drugs. Contrary to the popular notion that offenders who have substance use disorders are best dealt with by adjudication and sanctions, DTCs embrace the scientific premise that substance use disorders are chronic, often relapsing medical conditions (5).

The authoritative and supervisory power of a judge is critical to this approach to treatment. However, the participation of a judge in the rehabilitation process represents a dramatic shift in legal thought and judicial behavior.

A NEW APPROACH TO AN OLD PROBLEM

Through the collaborative efforts of defense attorneys and prosecutors, treatment providers, court coordinators or case managers, community policing agencies, and community corrections officials, a criminal defendant in a DTC is given an opportunity to engage in an alternative to the criminal “business as usual” and, in its place, to pursue a program of addiction treatment and recovery.

DTCs employ a series of incentives and sanctions to induce treatment compliance and lifestyle changes in criminal defendants. The ultimate reward for the participants is dismissal of charges, having a sentence set aside, or imposition of a lesser penalty. By choosing to participate in a DTC, criminal defendants avoid serving a substantial period of incarceration and gain sobriety and crime-free lifestyles. As the federal Bureau of Justice Assistance has defined it: “A [DTC] establishes an environment that the participant can understand: a system in which clear choices are presented and individuals are encouraged to take control of their own recovery” (6).

Further, DTCs integrate alcohol and other drug treatment services with justice system case processing. Their operations are defined by 10 key components:

1. Drug courts integrate alcohol and other drug treatment services with justice system case processing.

2. Using a nonadversarial approach, prosecutors and defense counsel work together to promote public safety while protecting participants’ due process rights.

3. Eligible participants are identified early and promptly placed in the drug court program.

4. DTCs provide access to a continuum of alcohol, drug, and related treatment and rehabilitation services.

5. Abstinence is monitored through frequent alcohol and other drug testing.

6. A coordinated strategy governs DTC responses to participants’ compliance.

7. Ongoing judicial interaction with each DTC participant is essential.

8. Monitoring and evaluation measure the achievement of program goals and gauge its effectiveness.

9. Continuing interdisciplinary education promotes effective DTC planning, implementation, and operations.

10. Forging partnerships among DTCs, public agencies, and community-based organizations generates local support and enhances the DTC’s effectiveness.

When these components are employed, the courtroom is transformed into an arena in which a judge is the central figure of a team that is focused on the participants’ recovery. The prosecutor screens each candidate for eligibility and verifies that he or she is appropriate for participation in a DTC. The defense counsel verifies that the client understands that DTC participation is voluntary and that he or she is aware of all legal options and makes a knowing and intelligent waiver of rights, including their confidentiality rights. Opposing counsel thus focus on the participants’ progress, rather than on the merits of the pending case. A close, interpersonal, and therapeutic relationship develops between the judge and the participants, who are encouraged to develop the tools they need to maintain sobriety and recovery.

Participants often enter into written contracts, agreeing to certain behaviors (data show that such contracts are more likely to induce compliance, whether it is taking medication or engaging in addiction treatment) (7). A typical contract covers on-time appearances at treatment sessions, court dates, self-help meetings, and other appointments; compliance with all rules; waivers of confidentiality; payment of fees and fines; participating in urine tests without water loading, adulteration, or counterfeiting; an agreement to refrain from alcohol or other drug use or contact with individuals who engage in such use; an agreement to abstain from eating poppy seeds, taking over-the-counter or prescription medications without prior approval, or other conduct that could yield a false result on a urine test; and agreeing to a 12- to 18-month commitment to treatment.

Although judges remain the final arbiter of all issues, they receive input from the entire team, including arrestees. If a problem arises, such as a use episode, it is not unusual for a participant to arrive in court having already discussed the problem with the treatment provider and a probation officer or court coordinator, who presents a recommendation to the judge (which might involve jail time, increased meetings, or increased urine tests). When participants themselves propose the sanctions, they are more likely to comply with them, not to feel coerced by the “system” or the judge, and to consider them fair.

Confidentiality waivers are mandatory, as are waivers of judicial ethical issues such as the prohibition on ex parte communications, simply because the treatment providers, mental health professionals, and physicians must be able to communicate with the court coordinator/case manager and the team. Written waivers that comply with federal statutes are mandatory. Judges must be able to talk to team members individually throughout the week without inhibition. Participants must understand their rights to confidentiality and the judges’ prohibition on ex parte communication and be willing to provide a written waiver as a condition of entering DTC.

This team concept of DTCs uniquely facilitates participants’ treatment progress. It is not unusual for participants to ask that the arresting officer be present at their graduation from the program. Police officers, including the bailiff in the courtroom, become supporters and benefactors rather than enemies. Similarly, supporting actors such a community-based treatment providers, community policing officers, housing authority personnel, mental health professionals, and physicians develop a unique relationship with the courts and a voice not previously heard.

Most DTCs have three phases:

1. An initiation of abstinence phase, in which participants come to court weekly

2. A treatment phase, in which participants meet with the judge twice a month

3. A relapse prevention phase, with monthly court dates

Frequent contact with and monitoring by the judge are essential to the success of DTC participants. The court monitors participants’ treatment program attendance and drug test results. As the ultimate authority figure in this system, the judge also is important in motivating and encouraging participants. The judge praises, cajoles, kids, threatens, harangues, and does whatever it takes to keep participants in treatment and recovery. Treatment may be delivered in a variety of settings, including community-based programs; day treatment; in a variety of outpatient, inpatient, and residential settings; and in custody.

Using graduated sanctions, the court usually begins with the least restrictive model, as indicated by an assessment tool such as the addiction severity index (Table 113-2). Participants are moved to more or less restrictive placements as needed. Placing participants in a more restrictive environment is not phrased in terms of punishment; rather, participants are encouraged to see the change as necessary to their recovery. Likewise, a move to outpatient treatment is presented as a reward for desired behaviors. At intake, a social needs assessment is completed, along with an alcohol and drug use assessment. Mental health, housing, physical health, employment, education, and other legal entanglements are addressed. Periods of abstinence— confirmed by weekly, random urine drug tests—are required for each phase, typically at 30, 90, and 180 days.

TABLE 113-2 ADVICE FOR ASSESSING DRUG TREATMENT COURT CLIENTS

DTC, drug treatment court.

DTCs provide aftercare planning, and participants petition the court to “graduate,” typically at about 180 days of sobriety. This requires 12 to 24 months, although some courts retain participants for years. To receive approval to graduate, participants must demonstrate insight into addiction and have a plan for relapse prevention. Participants also are invited to become involved in a DTC alumni group. To graduate, participants must have a clean and sober living environment, as well as full-time employment or full-time student status or, if disabled, a source of income such as Social Security, and all fees and fines must be paid or substantial amounts of volunteer work completed. Graduating participants also must have driver’s licenses, insurance, and proof of registration of all vehicles and be able to show that they have no outstanding tickets or warrants. They must have a high school diploma or general educational diploma (unless they are unable to obtain one because of cognitive deficits or lack of numeracy or literacy) and either take literacy classes, if they are English speaking, or enroll in a class for students learning English as a second language. Abstinence alone is not enough.

When a participant submits a positive urine test, misses meetings or appointments, fails to participate, or otherwise breaks program rules, sanctions are imposed immediately. Such sanctions may include paying the cost of the urine test, increased meeting attendance (e.g., 30 meetings in 30 days), demotion to an earlier phase of the program, a requirement to perform volunteer work, or short stints of jail time (usually 1 day to no more than 1 week at a time). The ultimate sanction is removal from the program and (in a preplea model) reentry into the criminal system or (after adjudication) sentencing, including incarceration. Consistent noncompliance may trigger a mental health assessment, as many DTC participants have undiagnosed comorbid mental health problems such as clinical depression, PTSD, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia. Program dismissal is reserved for the most serious offenses, such as attempts to falsify or adulterate a urine sample, leaving without permission, threatening staff, or arrest for a violent offense.

The focus of the DTC team is on treatment compliance and program retention rather than punishment. It is the goal of the DTC team to keep participants in treatment, to support their recovery, and to encourage participants by emphasizing their abilities and strengths. Rewards may include a reduction of program fees, a reduction in the number of court appearances, and awarding of certificates (with much cheering and applause from the audience) to mark the completion of each phase. Simple praise from a judge is a potent incentive, as is a drawing for a small gift. One study showed that the opportunity to draw from a fish bowl increased stimulant users’ success in treatment fourfold (8,9).

In DTCs, it is not unusual to hear a public defender recommend jail time, while a prosecutor argues that only increased meetings are required. The adversarial system is put on hold in DTCs; defense counsel and the prosecution are equal team members whose interest is in treatment and recovery, not convictions or acquittals. At any point in the process, participants may opt out of the DTC and into the traditional criminal justice case processing system, with all the attendant rights and remedies.

WHY DRUG TREATMENT COURTS WORK

There is support for DTCs on many fronts and from all points on the political spectrum (10–13). First, it is clear that coerced treatment works. Research indicates that a person coerced to enter treatment by the criminal justice system is likely to do as well as one who enters voluntarily (14–19). In fact, there is debate about the “voluntariness” of any addiction treatment, because most addicts come to treatment as the result of legal or marital problems, other concerns in their personal lives, problems with job performance, or for health reasons (20). Second, addiction treatment is as successful as treatment for other chronic diseases and saves $7 for every dollar spent on treatment (5). Moreover, because of the requirement for interdisciplinary training, DTC judges and other team members are aware of the likelihood of relapse and know how to respond appropriately. DTCs are in a unique position to recognize these temporary setbacks as learning experiences for the participant and the treatment team.

A study that assessed the effectiveness of DTCs (12) examined nine adult drug courts in California. Using a Transactional Institutional Costs Analysis approach, the investigators calculated costs based on every subject’s transactions within the drug court or the traditional criminal justice system. This method allowed the calculation of costs and benefits by agency (e.g., the public defender’s office, court, district attorney). Results in the nine sites showed that the majority of agencies saved money when offenders were processed through a drug court. Overall, participation in drug courts saved the state more than $9 million in criminal justice and treatment costs (largely from reduced recidivism among drug court participants). Green et al. (21) and Henggeler (15) reported similar results in their studies of family DTCs. Werb et al. (22) conducted a review of DTCs in Canada and found positive short-term outcomes. However, like other investigators, Werb pointed to the need for long-term follow-up studies to reach definitive conclusions about the effectiveness of drug courts.

The largest studies of the efficacy of DTCs have been undertaken by the Northwest Professional Consortium Research in Portland, Oregon. Data they have collected on hundreds of DTCs show that, when there is fidelity to the 10 Key Components (described above), DTCs reduce both costs and recidivism rates (23). The U.S. Government Accountability Office found that participants in DTCs have rearrest rates that are 12% to 58% points lower than those in a comparison group of arrestees who did not participate in DTCs (24).

Courts have come to accept that their role is changing from that of a neutral, uninvolved arbiter to a problem solver that deals with cases holistically. There also is support for the proposition that judicial job satisfaction is increased if judges work therapeutically (25). In 2001, the U.S. Conference of Chief Justices and the Conference of State Court Administrators adopted a joint resolution endorsing DTCs and problem-solving courts based on the drug court model, the first resolution of its kind. The resolution commits all 50 chief justices and state court administrators “to take steps nationally and locally to expand the principles and methods of well functioning drug courts into ongoing court operations.” It also pledges to “encourage the broad integration, over the next decade, of the principles and methods employed in problem-solving courts into the administration of justice” (26).

Law enforcement support for DTCs is strong because officers see that recovery presents a long-term solution to a community’s and an individual’s problems with alcohol or other drugs. Formal liaisons between community police and DTCs are encouraged through the Community Policing Mentor Court Network of the National Association of Drug Court Professionals.

THE COURTS AND PHYSICIANS WORKING TOGETHER

“Given what is known about the many social, medical, and legal consequences of drug abuse, effective drug abuse treatment should, at a minimum, be integrated with criminal justice, social, and medical services” (Executive Office of the President, The White House, 2000) (27). DTCs and the criminal justice system can be powerful allies for addiction medicine specialists.

Through DTCs, physicians and judges have initiated a new dialogue about alcohol and other drug problems. The partnership has extended to other venues, as well: Judges have participated in Congressional and U.S. mayoral briefings. Judges have presented programs at meetings of the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM). Addiction medicine specialists teach courses on alcohol and other drug problems at the National Judicial College and in many state training programs. The time is ripe for local coalitions of judges and other leaders in the criminal justice system to collaborate with addiction medicine specialists to educate one another on how to be more effective in working with their mutual clients/patients. Judges in the criminal justice system may have more to say about a patient’s treatment that the physician does, while physicians may wish to add questions relating to involvement with the justice system to patient assessments as a case-finding tool for alcohol and other drug problems.

Physicians should acquaint themselves with their local DTCs and, if none is available locally, join a community coalition to ask that one be established. Most courts have long-range strategic, operational, and action plans developed with community input; DTCs should be part of those plans. Local grand juries, with the help of addiction medicine specialists, should study DTCs and make recommendations for appropriate use of such courts in their own communities. State chapters of ASAM should make experts available to judges who have questions about alcohol and other drug issues. Judges have the power to appoint such physicians as expert advisors to the court.

We are at a unique place in our history that will foster new and exciting collaborations. Let this chapter be but a first step.

Therapeutic Jurisprudence

Therapeutic jurisprudence is the study of the law’s healing potential (1–3). As an interdisciplinary approach to legal scholarship that has a reform agenda, therapeutic jurisprudence seeks to assess the therapeutic and countertherapeutic consequences of the law and the ways in which it is applied, as well as to increase the former and diminish the latter. It is an approach to the law that uses the tools of the behavioral sciences to assess the law’s therapeutic effects and, consistent with other important legal values, to reshape law and legal processes in ways that can improve the psychological functioning and emotional well-being of the affected individuals (4).

PHILOSOPHIC ROOTS OF THERAPEUTIC JURISPRUDENCE

Schma (4) has noted that therapeutic jurisprudence is one of the major vectors of a growing movement in the law “towards a common goal of a more comprehensive, humane, and psychologically optimal way of handling legal matters.” In addition to therapeutic jurisprudence, those vectors include (among others) preventive law, restorative justice, facilitative mediation, holistic law, collaborative divorce, and specialized treatment courts. Such specialized courts—“problem-solving courts,” as they are becoming known—include drug treatment courts (DTCs) (5), domestic violence courts (6,7), and mental health courts (8,9).

Specialized treatment courts such as DTCs are related to therapeutic jurisprudence (5), but are not synonymous with that concept. However, specialized treatment courts often employ the principles of therapeutic jurisprudence to enhance their functioning (10). Such principles include ongoing judicial intervention, close monitoring of and immediate response to behavior, integration of treatment services with judicial case processing, multidisciplinary involvement, and collaboration with community-based and government agencies and organizations.

THERAPEUTIC JURISPRUDENCE IN DRUG COURTS

Therapeutic jurisprudence was developed in the late 1980s as an interdisciplinary approach to legal scholarship and law reform. Although DTCs developed independent of therapeutic jurisprudence, they can be seen as taking a complementary approach to the processing of drug cases, inasmuch as their mutual goal is the rehabilitation of the offender.

Therapeutic jurisprudence already has produced a large body of interdisciplinary scholarship that analyzes principles of psychology and the behavioral sciences and attempts to understand how those principles can be used within the legal system to improve mental health outcomes (1). Recent scholarship has focused on how judges in specialized problem-solving courts can employ the principles of therapeutic jurisprudence in their work (6,7,9–11).

An important insight of therapeutic jurisprudence is that the way in which judges and other court officers fulfill their roles has inevitable consequences for the mental health and psychological well-being of the persons with whom they interact. Because DTC judges consciously view themselves as therapeutic agents in dealing with offenders, they can be seen as playing a therapeutic jurisprudence role. In fact, an understanding of the approach of therapeutic jurisprudence and of the psychological and social work principles it employs can improve the functioning of DTC judges.

Interactions between judges and defendants are central to the functioning of DTCs. Judges therefore need to understand how to convey empathy, how to recognize and deal with denial, and how to apply principles of behavioral psychology and motivational theory. They need to understand the psychology of procedural justice, which teaches that persons appearing in court experience greater satisfaction and comply more willingly with court orders when they are given a sense of voice and validation and treated with dignity and respect (Winick, 1999) (11A).

Judges need to know how to structure court practices in ways that maximize their therapeutic potential. For example, even such mundane matters as the order of cases to be heard can maximize the chance that defendants awaiting their turn before the judge can experience vicarious learning. Offenders who accept diversion to DTCs are, in effect, entering into a type of behavioral contract with the court, and judges therefore should understand the psychology of such behavioral contracting and how it can be used to increase motivation, compliance, and effective performance (2,12).

DTC judges also need to understand how to deal with feelings of coercion on the part of offenders (13). A degree of legal coercion is undeniably present when a drug offender is arrested and must decide whether to face the consequences of trial and potential punishment in the criminal court or instead accept diversion and a course of treatment supervised by a DTC. However, a body of literature on the psychology of choice suggests that if the defendant experiences this choice as coerced, his or her attitude, motivation, and chances for success in the treatment program may be undermined. On the other hand, experiencing the choice as voluntarily made and non-coerced is more conducive to success. Therefore, judges should not attempt to pressure offenders to accept diversion to a DTC but instead should remind them that the choice is entirely theirs.

A body of psychological work on what makes individuals feel coerced suggests that judges should strive to treat offenders with dignity and respect, to inspire trust and confidence that the judges have their best interests at heart, to provide them a full opportunity to participate, and to listen attentively to what offenders have to say. Judges who treat drug court offenders in this fashion increase the likelihood that the offender will experience treatment as a voluntary choice, will internalize the goals of treatment, and will act in ways that help to achieve those goals.

While therapeutic jurisprudence can help drug court judges more effectively fulfill their roles in the drug treatment process, it is important to recognize that therapeutic jurisprudence does not necessarily support all actions that may be regarded as protreatment. Nor does therapeutic jurisprudence take a position as to whether increased or reduced criminalization or penalties for possession of drugs are warranted. Indeed, unless there are independent justifications for criminalization, therapeutic jurisprudence would not support continued criminalization solely to provide a stick-and-carrot approach to inducing criminal defendants to accept treatment in a drug court diversion program.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, therapeutic jurisprudence can contribute much to the functioning of DTCs, and such courts can provide rich laboratories from which to generate and refine approaches to therapeutic jurisprudence. However, the two perspectives are merely vectors moving in a common direction, not identical concepts.

Therapeutic jurisprudence and DTCs share a common cause as they strive to understand how legal rules and court practices can be designed to facilitate the rehabilitative process. Each has much to offer the other (14,15).

REFERENCES

1.Wexler DB, Winick BJ. Law in a therapeutic key: developments in therapeutic jurisprudence. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 1996.

2.Wexler DB. Inducing therapeutic compliance through the criminal law. In: DB Wexler, BJ Winick, eds. Essays in therapeutic jurisprudence. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 1991:187–198.

3.Winick BJ. The jurisprudence of therapeutic jurisprudence. Psychology Public Policy Law 1997;3:184–206.

4.Schma W. Therapeutic jurisprudence: using the law to improve the public’s health. J Law Med Ethics 2005;33(Suppl 4):59–63.

5.Hora PF, Schma WG, Rosenthal JTA. Therapeutic jurisprudence and drug treatment court movement: revolutionizing the criminal justice system’s response to drug abuse and crime in America. Notre Dame Law Review 1999;74:439–537.

6.Fritzler RB, Simon LMJ. The development of a specialized domestic violence court in Vancouver, Washington utilizing innovative judicial paradigms. UMKC L Rev 2000;69:139–177.

7.Winick BJ. Applying the law therapeutically in domestic violence cases. UMKC L Rev 2000;69:33–91.

8.Rottman DB, Casey P. Therapeutic jurisprudence and the emergence of problem-solving courts. Natl Inst Justice J 1999:12–19.

9.Casey P, Rottman DB. Therapeutic jurisprudence in the courts. Behav Sci Law 2000;18:445–457.

10. Conference of Chief Justices and Conference of State Court Administrators. CCJ Resolution 22 & COSCA Resolution 4. In support of problem-solving courts. 2000

11. Court Review. Special issue on therapeutic jurisprudence. Court Rev 2000;37:1–68.

12. Winick BJ. Redefining the role of the criminal defense lawyer at plea bargaining and sentencing: a therapeutic jurisprudence/preventive law model, 5. Psychology, Public Policy, Low 1999;1034.

13. Winick BJ. Harnessing the power of the bet: wagering with the government as a mechanism of social and individual change. In: Wexler DB, Winick BJ, eds. Essays in therapeutic jurisprudence. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 1991:219–290.

14. Daicoff S. The role of therapeutic jurisprudence within the comprehensive law movement. In: Stolle DP, Wexler DB, Winick BJ, eds. Practicing therapeutic jurisprudence: law as a helping profession. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2000:465–492.

15. Wexler DB, Winick BJ. Essays in therapeutic jurisprudence. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 1991.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree