Drug Therapy of Depression and Anxiety Disorders

Depression and anxiety disorders are the most common mental illnesses, each affecting in excess of 10-15% of the population at some time in their lives. With the advent of more selective and safer drugs, the use of antidepressants and anxiolytics has moved from the domain of psychiatry to other medical specialties, including primary care. The relative safety of the majority of commonly used antidepressants and anxiolytics notwithstanding, their optimal use requires a clear understanding of their mechanisms of action, pharmacokinetics, potential drug interactions, and the differential diagnosis of psychiatric illnesses.

A confluence of symptoms of depression and anxiety may affect an individual patient; some of the drugs discussed here are effective in treating both disorders, suggesting common underlying mechanisms of pathophysiology and response to pharmacotherapy. In large measure, our current understanding of pathophysiological mechanisms underlying depression and anxiety has been inferred from the mechanisms of action of psychopharmacological compounds (see Chapter 14). While depression and anxiety disorders comprise a wide range of symptoms, including changes in mood, behavior, somatic function, and cognition, some progress has been made in developing animal models that respond with some sensitivity and selectivity to antidepressant or anxiolytic drugs. The last half century has seen notable advances in the discovery and development of drugs for treating depression and anxiety.

CHARACTERIZATION OF DEPRESSIVE AND ANXIETY DISORDER

SYMPTOMS OF DEPRESSION

Depression is classified as major depression (i.e., unipolar depression) or bipolar depression (i.e., manic depressive illness); bipolar depression and its treatment are discussed in Chapter 16. Lifetime risk of unipolar depression is ~15%. Females are affected twice as frequently as males. Depressive episodes are characterized by sad mood, pessimistic worry, diminished interest in normal activities, mental slowing and poor concentration, insomnia or increased sleep, significant weight loss or gain due to altered eating and activity patterns, psychomotor agitation or retardation, feelings of guilt and worthlessness, decreased energy and libido, and suicidal ideation, occurring most days for a period of at least 2 weeks. In some cases, the primary complaint of patients involves somatic pain or other physical symptoms and can present a diagnostic challenge for primary care physicians. Depressive symptoms also can occur secondary to other illnesses such as hypothyroidism, Parkinson disease, and inflammatory conditions. Further, depression often complicates the management of other medical conditions (e.g., severe trauma, cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, especially myocardial infarction).

Depression is underdiagnosed and undertreated. Approximately 10-15% of those with severe depression attempt suicide at some time. Thus, it is important that symptoms of depression be recognized and treated in a timely manner. Furthermore, the response to treatment must be assessed and decisions made regarding continued treatment with the initial drug, dose adjustment, adjunctive therapy, or alternative medication.

SYMPTOMS OF ANXIETY. Anxiety disorder symptoms include generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), separation anxiety disorder, social phobia, specific phobias, and acute stress. In general, symptoms of anxiety that lead to pharmacological treatment are those that interfere significantly with normal function. Symptoms of anxiety also are often associated with depression and other medical conditions.

Anxiety is a normal human emotion that serves an adaptive function from a psychobiological perspective. However, in the psychiatric setting, feelings of fear or dread that are unfocused (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder) or out of scale with the perceived threat (e.g., specific phobias) often require treatment. Drug treatment includes acute drug administration to manage episodes of anxiety, and chronic or repeated treatment to manage unrelieved and continuing anxiety disorders.

ANTIDEPRESSANT DRUGS

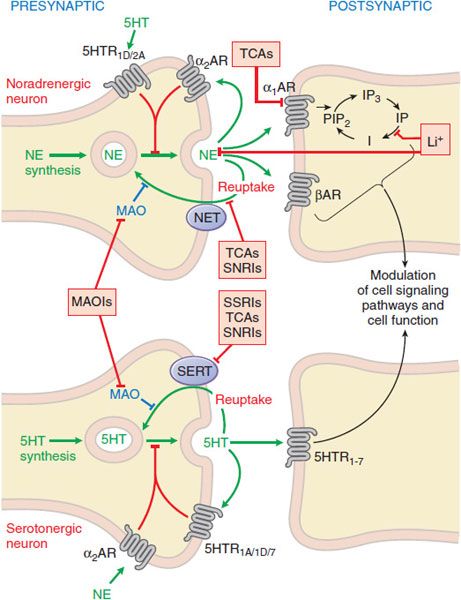

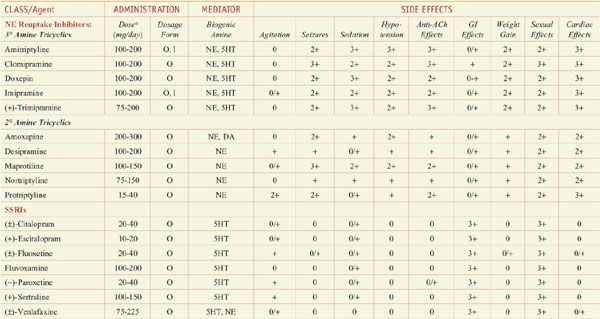

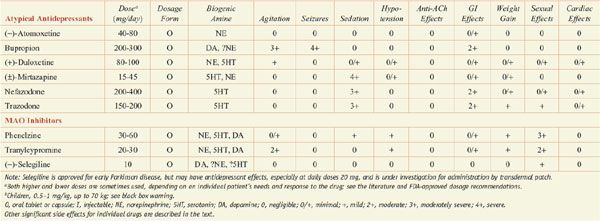

In general, antidepressants enhance serotonergic or noradrenergic transmission. Sites of interaction of antidepressant drugs with noradrenergic and serotonergic neurons are depicted in Figure 15–1. Table 15–1 summarizes the actions of the most widely used antidepressants. The most commonly used medications, often referred to as second-generation antidepressants, are the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), which have greater efficacy and safety compared to the first-generation drugs, which include monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs).

Figure 15–1 Sites of action of antidepressants at noradrenergic (top) and serotonergic (bottom) nerve terminals. SSRIs, SNRIs, and TCAs increase noradrenergic or serotonergic neurotransmission by blocking the NE or 5HT transporter at presynaptic terminals (NET, SERT). MAOIs inhibit the catabolism of NE and 5HT. Trazodone and related drugs have direct effects on 5HT receptors that contribute to their clinical effects. Chronic treatment with a number of antidepressants desensitizes presynaptic autoreceptors and heteroreceptors, producing long-lasting changes in monoaminergic neurotransmission. Post-receptor effects of antidepressant treatment, including modulation of GPCR signaling and activation of protein kinases and ion channels, are involved in the mediation of the long-term effects of antidepressant drugs. Note that NE and 5HT also affect each other’s neurons.

Antidepressants: Dose and Dosage Forms, and Side Effects

In monoamine systems, inhibition of reuptake can enhance neurotransmission, presumably by slowing clearance of the transmitter from the synapse and prolonging the dwell-time of the transmitter in the synapse. Reuptake inhibitors inhibit either SERT, the neuronal serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine [5HT]) transporter; NET, the neuronal norepinephrine (NE) transporter; or both. Similarly, MAOIs and TCAs enhance monoaminergic neurotransmission: the MAOIs by inhibiting monoamine metabolism and thereby enhancing neurotransmitter storage in secretory granules, the TCAs by inhibiting 5HT and NE reuptake

Long-term effects of antidepressant drugs evoke regulatory mechanisms that enhance the effectiveness of therapy. These responses include increased adrenergic or serotonergic receptor density or sensitivity, increased receptor-G protein coupling and cyclic nucleotide signaling, induction of neurotrophic factors, and increased neurogenesis in the hippocampus. Persistent antidepressant effects depend on the continued inhibition of 5HT or NE transporters, or enhanced serotonergic or noradrenergic neurotransmission achieved by an alternative pharmacological mechanism. Compelling evidence suggests that sustained signaling via NE or 5HT increases the expression of specific downstream gene products, particularly brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which appears to be related to the ultimate mechanism of action of these drugs.

CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS WITH ANTIDEPRESSANT DRUGS

Antidepressant drug treatment has generally a “therapeutic lag” lasting 3-4 weeks before a measurable therapeutic response becomes evident. After the successful initial treatment phase, a 6-12–month maintenance treatment phase is typical, after which the drug is gradually withdrawn. If a patient is chronically depressed (i.e., >2 years), lifelong treatment with an antidepressant is advisable.

A controversial issue regarding the use of all antidepressants is their relationship to suicide. Data establishing a clear link between antidepressant treatment and suicide are lacking. However, the FDA has issued a “black box” warning regarding the use of SSRIs and a number of other antidepressants in children and adolescents due to the possibility of an association between antidepressant treatment and suicide. For seriously depressed patients, the risk of not being on an effective antidepressant drug outweighs the risk of being treated with one.

SELECTIVE SEROTONIN REUPTAKE INHIBITORS

The SSRIs are effective in treating major depression. SSRIs also are anxiolytics with demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of generalized anxiety, panic, social anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorders. Sertraline and paroxetine are approved for the treatment of PTSD. SSRIs also are used for treatment of premenstrual dysphoric syndrome and for preventing vasovagal symptoms in postmenopausal women.

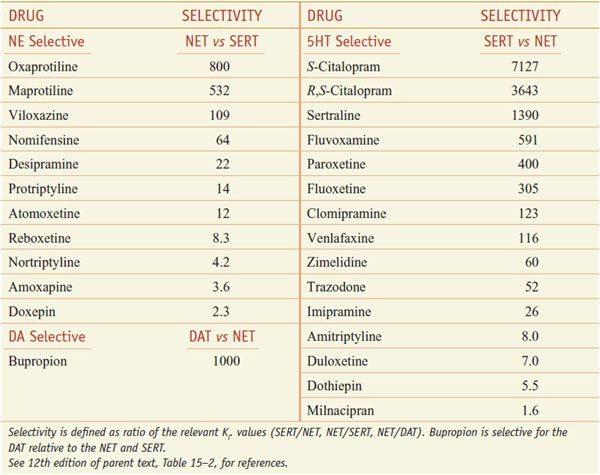

SERT mediates the reuptake of serotonin into the presynaptic terminal; neuronal uptake is the primary process by which neurotransmission via 5HT is terminated (see Figure 15–1). SSRIs block reuptake and prolong serotonergic neurotransmission. SSRIs used clinically are relatively selective for inhibition of SERT relative to NET (Table 15–2; not shown is vilazodone [VIIBRYD], an SSRI and partial 5HT1A agonist, recently approved by the FDA for treatment of major depression).

Table 15–2

Selectivity of Antidepressants at the Human Biogenic Amine Transporters

SSRI treatment causes stimulation of 5HT1A and 5HT7 autoreceptors on cell bodies in the raphe nucleus and of 5HT1D autoreceptors on serotonergic terminals, and this reduces serotonin synthesis and release toward predrug levels. With repeated treatment with SSRIs, there is a gradual downregulation and desensitization of these autoreceptor mechanisms. In addition, downregulation of postsynaptic 5HT2A receptors may contribute to antidepressant efficacy directly or by influencing the function of noradrenergic and other neurons via serotonergic heteroreceptors. Other postsynaptic 5HT receptors likely remain responsive to increased synaptic concentrations of 5HT and contribute to the therapeutic effects of the SSRIs.

Later-developing effects of SSRI treatment also may be important in mediating ultimate therapeutic responses. These include sustained increases in cyclic AMP signaling and phosphorylation of the nuclear transcription factor CREB, as well as increases in the expression of trophic factors such as BDNF, and increases of neurogenesis from progenitor cells in the hippocampus and subventricular zone. Repeated treatment with SSRIs reduces the expression of SERT, resulting in reduced clearance of released 5HT and increased serotonergic neurotransmission.

SEROTONIN-NOREPINEPHRINE REUPTAKE INHIBITORS

Four medications with a nontricyclic structure that inhibit the reuptake of both 5HT and NE have been approved for use in the U.S. for treatment of depression, anxiety disorders, and pain: venlafaxine and its demethylated metabolite, desvenlafaxine; duloxetine; and milnacipran.

SNRIs inhibit both SERT and NET (see Table 15–2) and cause enhanced serotonergic and/or noradrenergic neurotransmission. Similar to the action of SSRIs, the initial inhibition of SERT induces activation of 5HT1A and 5HT1D autoreceptors. This action decreases serotonergic neurotransmission by a negative feedback mechanism until these serotonergic autoreceptors are desensitized. Then, the enhanced serotonin concentration in the synapse can interact with postsynaptic 5HT receptors. SNRIs were developed with the rationale that they might improve overall treatment response compared to SSRIs. Specifically, the remission rate for venlafaxine appears slightly better than for SSRIs in head-to-head trials. Duloxetine, in addition to being approved for use in the treatment of depression and anxiety, also is used for treatment of fibromyalgia and neuropathic pain associated with peripheral neuropathy. Off-label uses include stress urinary incontinence (duloxetine), autism, binge eating disorders, hot flashes, pain syndromes, premenstrual dysphoric disorders, and PTSDs (venlafaxine).

SEROTONIN RECEPTOR ANTAGONISTS

Several antagonists of the 5HT2 family of receptors are effective antidepressants. These includes 2 close structural analogues, trazodone and nefazodone, as well as mirtazapine (REMERON, others) and mianserin (not marketed in the U.S.).

The efficacy of trazodone may be somewhat more limited than the SSRIs; however, low doses of trazodone (50-100 mg) have been used widely both alone and concurrently with SSRIs or SNRIs to treat insomnia. Both mianserin and mirtazapine are quite sedating and are treatments of choice for some depressed patients with insomnia. Trazodone blocks the 5HT2 and α1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree