14

Drug Addiction

This chapter will be most useful after having a basic understanding of the material in Chapter 24, Drug Addiction in Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 12th Edition. The specific pharmacology (including the mechanisms of action) of drugs mentioned in Chapter 14 is discussed in previous or subsequent chapters. The drugs presented in Chapter 14 are discussed in relation to their ability to produce tolerance, physical dependence, and addiction. No Mechanisms of Action Table nor Clinical Summary Table are included as a part of Chapter 14 because new drugs are not introduced. The few drugs that are used therapeutically to treat specific drug addictions are discussed in the narratives of the clinical cases. In addition to the material presented here, the 12th Edition includes:

• Table 24-2 Dependence among Users 1990 to 1992

• Figure 24-2 Cocaine-induced changes in CNS dopamine release

• Figure 24-3 Nicotine concentrations in blood resulting from five different nicotine delivery systems

• A detailed discussion of the variables affecting the onset and continuation of drug abuse and addiction

• A detailed discussion of the different types of tolerance

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Understand the pharmacological principles of tolerance, physical dependence, and withdrawal.

Understand the pharmacological principles of tolerance, physical dependence, and withdrawal.

Describe the characteristic withdrawal syndromes for the commonly abused drugs.

Describe the characteristic withdrawal syndromes for the commonly abused drugs.

Know the patterns of abuse behavior and the toxicity of the commonly abused drugs.

Know the patterns of abuse behavior and the toxicity of the commonly abused drugs.

Know the available pharmacological interventions for the acute treatment and long-term management of the commonly abused drugs.

Know the available pharmacological interventions for the acute treatment and long-term management of the commonly abused drugs.

A 56-year-old obese woman is being treated with immediate-release oxycodone for chronic back pain. She is also taking a muscle relaxant, cyclobenzaprine, and a short-acting benzodiazepine for sleep.

a. What concerns are there with the use of an opiate-like immediate-release oxycodone for the treatment of chronic pain?

Rapid-onset, short-duration opioids are excellent for acute short-term use, such as during the postoperative period. As tolerance and physical dependence develop, however, the patient may experience the early symptoms of withdrawal between doses, and during withdrawal, the threshold for pain decreases. The diversion of prescription opioids such as oxycodone and hydrocodone to illegal markets has become an important source of opiate abuse in the United States (see answer to Case 14-1c below).

The risk for addiction is highest in patients complaining of pain with no clear physical explanation or in patients with evidence of a chronic, non-life-threatening disorder. Examples are chronic headaches, backaches, abdominal pain, or peripheral neuropathy. Even in these cases, an opioid may be considered as a brief emergency treatment, but long-term treatment with opioids should be used only after other alternatives have been exhausted.

b. Over the past year this patient has doubled her dose of oxycodone. Why has she increased the dose of oxycodone?

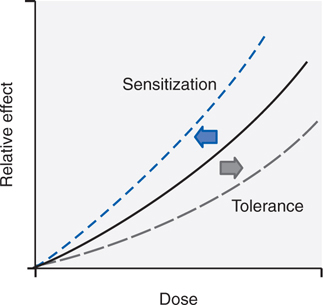

While abuse and addiction are complex conditions combining many variables (see Table 14-1), there are a number of relevant pharmacological phenomena that occur independent of social and psychological dimensions. First are the changes in the way the body responds to a drug with repeated use. Tolerance, the most common response to repetitive use of the same drug, can be defined as the reduction in response to the drug after repeated administrations. Figure 14-1 shows an idealized dose-response curve for an administered drug. As the dose of the drug increases, the observed effect of the drug increases. With repeated use of the drug, however, the curve shifts to the right (tolerance). Thus, a higher dose is required to produce the same effect that was once obtained at a lower dose. As outlined in Table 14-2, there are many forms of tolerance, likely arising through multiple mechanisms.

FIGURE 14-1 Shifts in a dose-response curve with tolerance and sensitization. With tolerance, there is a shift of the curve to the right such that doses higher than initial doses are required to achieve the same effects. With sensitization, there is a leftward shift of the curve such that for a given dose, there is a greater effect than seen after the initial dose.

TABLE 14-1 Multiple Simultaneous Variables Affecting Onset and Continuation of Drug Abuse and Addiction

Agent (drug)

Availability

Cost

Purity/potency

Mode of administration

Chewing (absorption via oral mucous membranes)

Gastrointestinal

Intranasal

Subcutaneous and intramuscular

Intravenous

Inhalation

Speed of onset and termination of effects (pharmacokinetics: combination of agent and host)

Host (user)

Heredity

Innate tolerance

Speed of developing acquired tolerance

Likelihood of experiencing intoxication as pleasure

Metabolism of the drug (nicotine and alcohol data already available)

Psychiatric symptoms

Prior experiences/expectations

Propensity for risk-taking behavior

Environment

Social setting

Community attitudes

Peer influence, role models

Availability of other reinforcers (sources of pleasure or recreation)

Employment or educational opportunities

Conditioned stimuli: environmental cues become associated with drugs after repeated use in the same environment

Innate (pre-existing sensitivity or insensitivity)

Acquired

Pharmacokinetic (dispositional or metabolic)

Pharmacodynamic

Learned tolerance

Behavioral

Conditioned

Acute tolerance

Reverse tolerance (sensitization)

Cross-tolerance

Tolerance to some drug effects develops much more rapidly than to other effects of the same drug. For example, tolerance develops rapidly to the euphoria produced by opioids such as heroin, and addicts tend to increase their dose in order to reexperience that elusive “high.” In contrast, tolerance to the gastrointestinal effects of opioids develops more slowly. The discrepancy between tolerance to euphorigenic effects (rapid) and tolerance to effects on vital functions (slow), such as respiration and blood pressure, can lead to potentially fatal overdoses in sedative abusers trying to reexperience the euphoria they recall from earlier use (see Case 14-5).

c. What are the options for treatment of this patient?

For chronic administration, long-acting opioids are preferred. While methadone is long-acting because of its metabolism to active metabolites, the long-acting version of oxycodone has been formulated to release slowly, thereby changing a short-acting opioid into a long-acting one. Unfortunately, this mechanism can be subverted by breaking the tablet and making the full dose of oxycodone immediately available. This has led to diversion of oxycodone to illicit traffic because high-dose oxycodone produces euphoria that is sought by opiate abusers.

A 43-year-old man is admitted to the hospital because of a fractured hip. He has a long history of alcohol consumption. Recently he has begun taking a drink of alcohol in the morning.

a. Is it appropriate to assume that he has developed tolerance and physical dependence to alcohol?

Heavy consumers of alcohol not only acquire tolerance but also inevitably develop a state of physical dependence. This often leads to drinking in the morning to restore blood alcohol levels diminished during the night. Eventually, they may awaken during the night and take a drink to avoid the restlessness produced by falling alcohol levels.

b. What are the major signs and symptoms of alcohol withdrawal?

The alcohol-withdrawal syndrome (see Table 14-3) generally depends on the size of the average daily dose and usually is “treated” by resumption of alcohol ingestion. Withdrawal symptoms are experienced frequently but usually are not severe or life-threatening until they occur in conjunction with other problems, such as infection, trauma, malnutrition, or electrolyte imbalance. In the setting of such complications, the syndrome of delirium tremens becomes likely.

TABLE 14-3 Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome

Alcohol craving

Tremor, irritability

Nausea

Sleep disturbance

Tachycardia

Hypertension

Sweating

Perceptual distortion

Seizures (6-48 hours after last drink)

Visual (and occasionally auditory or tactile) hallucinations (12-48 hours after last drink)

Delirium tremens (48-96 hours after last drink; rare in uncomplicated withdrawal)

Severe agitation

Confusion

Fever, profuse sweating

Tachycardia

Nausea, diarrhea

Dilated pupils

c. What is the appropriate treatment to prevent and treat alcohol withdrawal?

A patient who presents in a medical setting with an alcohol-withdrawal syndrome should be considered to have a potentially lethal condition. Although most mild cases of alcohol withdrawal never come to medical attention, severe cases require general evaluation; attention to hydration and electrolytes; vitamins, especially high-dose thiamine (see Chapter 9); and a sedating medication that has cross-tolerance with alcohol. To block or diminish the symptoms described in Table 14-3, a short-acting benzodiazepine such as oxazepam can be used at a dose of 15 to 30 mg every 6 to 8 hours according to the stage and severity of withdrawal; some authorities recommend a long-acting benzodiazepine unless there is demonstrated liver impairment. Anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine have been shown to be effective in alcohol withdrawal, although they appear not to relieve subjective symptoms as well as benzodiazepines. After medical evaluation, uncomplicated alcohol withdrawal can be treated effectively on an outpatient basis. When there are medical problems, a history of seizures, or simultaneous dependence on other drugs, hospitalization is required.

d. What are the options for this patient if he desires treatment for his alcoholism upon discharge from the hospital?

Detoxification is only the first step of treatment. Complete abstinence is the objective of long-term treatment, and this is accomplished mainly by behavioral approaches. Medications that aid in the prevention of relapse are under development. Disulfiram (ANTABUSE; see Chapter 9) has been useful in some programs that focus behavioral efforts on ingestion of the medication. Disulfiram blocks aldehyde dehydrogenase, the second step in ethanol metabolism, resulting in the accumulation of acetaldehyde, which produces an unpleasant flushing reaction when alcohol is ingested. Knowledge of this unpleasant reaction helps the patient to resist taking a drink. Although quite effective pharmacologically, disulfiram has not been found to be effective in controlled clinical trials because so many patients failed to ingest the medication.

Naltrexone (REVIA; see Chapter 10), an opioid receptor antagonist that blocks the reinforcing properties of alcohol, is FDA-approved as an adjunct in the treatment of alcoholism. Chronic administration of naltrexone resulted in a decreased rate of relapse to alcohol drinking in the majority of published double-blind clinical trials. It works best in combination with behavioral treatment programs that encourage adherence to medication and abstinence from alcohol. A depot preparation of naltrexone with a duration of 30 days (VIVITROL) was approved by the FDA in 2006; it greatly improves medication adherence, the major problem with the use of medications in treating alcoholism.

Acamprosate (CAMPRAL; see Chapter 9), another FDA-approved medication for alcoholism, is a competitive inhibitor of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)–type glutamate receptor. The drug appears to normalize the dysregulated neurotransmission associated with chronic ethanol intake and thereby to attenuate one of the mechanisms that lead to relapse.

A 75-year-old woman with early dementia has been taking alprazolam as a sleep aid for the past 10 years. She has consistently taken the same prescribed dose, but when her prescription expired she forgot to renew it.

a. Is she likely to have developed tolerance or physical dependence to the benzodiazepine?

When a benzodiazepine is taken for up to several weeks, there is little tolerance or physical dependence and no difficulty in stopping the medication when the condition no longer warrants its use. After several months, the proportion of patients who demonstrate physical dependence increases, and reducing the dose or stopping the medication abruptly produces withdrawal symptoms (see Table 14-4).

TABLE 14-4 Benzodiazepine Withdrawal Symptoms

Following moderate dose usage

Anxiety, agitation

Increased sensitivity to light and sound

Paresthesias, strange sensations

Muscle cramps

Myoclonic jerks

Sleep disturbance

Dizziness

Following high-dose usage

Seizures

Delirium

b. What symptoms might she experience as a result of abruptly stopping the benzodiazepine?

It can be difficult to distinguish withdrawal symptoms (see Table 14-4) from the reappearance of the anxiety symptoms for which the benzodiazepine was prescribed initially. Some patients may increase their dose over time because tolerance definitely develops to the sedative effects. Many patients and their physicians, however, contend that antianxiety benefits continue to occur long after tolerance develops to the sedating effects. Moreover, these patients continue to take the medication for years according to medical directions without increasing their dose and are able to function very effectively as long as they take the benzodiazepine. The degree to which tolerance develops to the anxiolytic effects of benzodiazepines is a subject of controversy.

c. How might this patient’s withdrawal syndrome be treated?

If patients receiving long-term benzodiazepine treatment by prescription wish to stop their medication, the process may take months of gradual dose reduction. Withdrawal symptoms (see Table 14-4) may occur during this outpatient detoxification, but in most cases the symptoms are mild. If anxiety symptoms return, a nonbenzodiazepine such as buspirone may be prescribed, but this agent usually is less effective than benzodiazepines for treatment of anxiety in these patients. Some authorities recommend transferring the patient to a long t1/2 benzodiazepine during detoxification; others recommend an anticonvulsant, carbamazepine or phenobarbital. Controlled studies comparing different treatment regimens are lacking. Since patients who have been on low doses of benzodiazepines for years usually have no adverse effects, the physician and patient should decide jointly whether detoxification and possible transfer to a new anxiolytic are worth the effort.

After detoxification, the prevention of relapse requires a long-term outpatient rehabilitation program similar to the treatment of alcoholism. No specific medications have been found to be useful in the rehabilitation of sedative abusers; but, of course, specific psychiatric disorders such as depression or schizophrenia, if present, require appropriate medications.

A 53-year-old man has been smoking since he was a teenager. He now desires to quit smoking.

a. What are the issues of nicotine addiction that should be considered in this patient?

The basic pharmacology of nicotine and agents for smoking cessation are discussed in Chapter 6. Because nicotine provides the reinforcement for cigarette smoking, the most common cause of preventable death and disease in the United States, it is arguably the most dangerous dependence-producing drug. The dependence produced by nicotine can be extremely durable, as exemplified by the high failure rate among smokers who try to quit. Although more than 80% of smokers express a desire to quit, only 35% try to stop each year, and fewer than 5% are successful in unaided attempts to quit.

Cigarette addiction is influenced by multiple variables. Nicotine itself produces reinforcement; users compare nicotine to stimulants such as cocaine or amphetamine, although its effects are of lower magnitude. While there are many casual users of alcohol and cocaine, few individuals who smoke cigarettes smoke a small enough quantity (≤5 cigarettes per day) to avoid dependence. Nicotine is absorbed readily through the skin, mucous membranes, and lungs. The pulmonary route produces discernible CNS effects in as little as 7 seconds. Thus, each puff produces some discrete reinforcement. With 10 puffs per cigarette, the 1-pack-per-day smoker reinforces the habit 200 times daily. The timing, setting, situation, and preparation all become associated repetitively with the effects of nicotine.

There is evidence for tolerance to the subjective effects of nicotine. Smokers typically report that the first cigarette of the day after a night of abstinence gives the “best” feeling. Smokers who return to cigarettes after a period of abstinence may experience nausea if they return immediately to their previous dose. Persons naive to the effects of nicotine will experience nausea at low nicotine blood levels, and smokers will experience nausea if nicotine levels are raised above their accustomed levels.

Negative reinforcement refers to the benefits obtained from the termination of an unpleasant state. In dependent smokers, the urge to smoke correlates with a low blood nicotine level, as though smoking were a means to achieve a certain nicotine level and thus avoid withdrawal symptoms. Some smokers even awaken during the night to have a cigarette, which ameliorates the effect of low nicotine blood levels that could disrupt sleep. Thus, smokers may be smoking to achieve the reward of nicotine effects, to avoid the pain of nicotine withdrawal, or most likely a combination of the two. Nicotine withdrawal symptoms are listed in Table 14-5.

TABLE 14-5 Nicotine Withdrawal Symptoms

Irritability, impatience, hostility

Anxiety

Dysphoric or depressed mood

Difficulty concentrating

Restlessness

Decreased heart rate

Increased appetite or weight gain

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree