Drug Addiction

The terminology used in discussing drug dependence, abuse, and addiction has long been confusing. Confusion stems from the fact that repeated use of certain prescribed medications can produce neuroplastic changes resulting in 2 distinctly abnormal states. The first is dependence, or “physical” dependence, produced when there is progressive pharmacological adaptation to the drug resulting in tolerance. In the tolerant state, repeating the same dose of drug produces a smaller effect. If the drug is abruptly stopped, a withdrawal syndrome ensues in which the adaptive responses are now unopposed by the drug. The appearance of withdrawal symptoms is the cardinal sign of “physical” dependence. Addiction, the second abnormal state produced by repeated drug use, occurs in only a minority of those who initiate drug use; addiction leads progressively to compulsive, out-of-control drug use.

Addiction can be defined fundamentally as a form of maladaptive memory. It begins with the administration of substances (e.g., cocaine) or behaviors (e.g., the thrill of gambling) that directly and intensely activate brain reward circuits. Activation of these circuits motivates normal behavior and most humans simply enjoy the experience without being compelled to repeat it. For some (~16% of those who try cocaine) the experience produces strong conditioned associations to environmental cues that signal the availability of the drug or the behavior. The individual becomes drawn into compulsive repetition of the experience focusing on the immediate pleasure despite negative long-term consequences and neglect of important social responsibilities. The distinction between dependence and addiction is important because patients with pain sometimes are deprived of adequate opioid medication simply because they have shown evidence of tolerance or they exhibit withdrawal symptoms if the analgesic medication is stopped or reduced abruptly.

ORIGINS OF SUBSTANCE DEPENDENCE

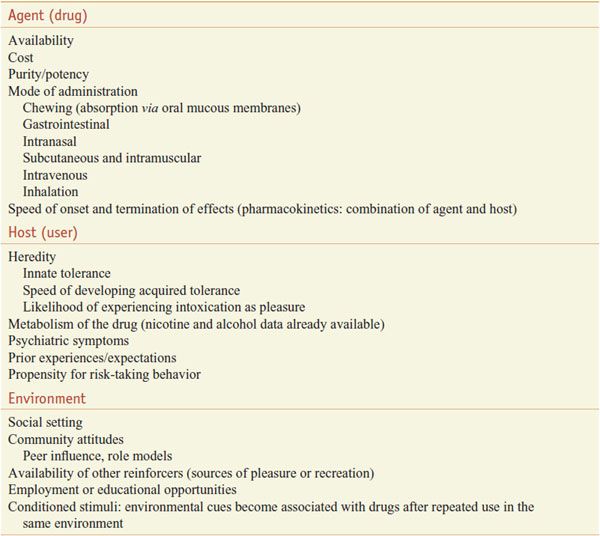

Most of those who initiate drug use do not progress to become addicts. Many variables operate simultaneously to influence the likelihood that a beginning drug user will lose control and develop an addiction. These variables can be organized into 3 categories: agent (drug), host (user), and environment (Table 24–1).

Table 24–1

Multiple Simultaneous Variables Affecting Onset and Continuation of Drug Abuse and Addiction

AGENT (DRUG) VARIABLES. Reinforcement refers to the capacity of drugs to produce effects that make the user wish to take them again. The more strongly reinforcing a drug is, the greater is the likelihood that the drug will be abused. Reinforcing properties of drugs are associated with their capacity to increase neuronal activity in critical brain areas (see Chapter 14). Cocaine, amphetamine, ethanol, opiates, cannabinoids, and nicotine all reliably increase extracellular fluid dopamine (DA) levels in the ventral striatum, specifically the nucleus accumbens region. In contrast, drugs that block DA receptors generally produce bad feelings, i.e., dysphoric effects. Despite strong correlative findings, a causal relationship between DA and euphoria/dysphoria has not been established, and other findings emphasize additional roles of serotonin (5HT), glutamate, norepinephrine (NE), endogenous opioids, and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in mediating the reinforcing effects of drugs.

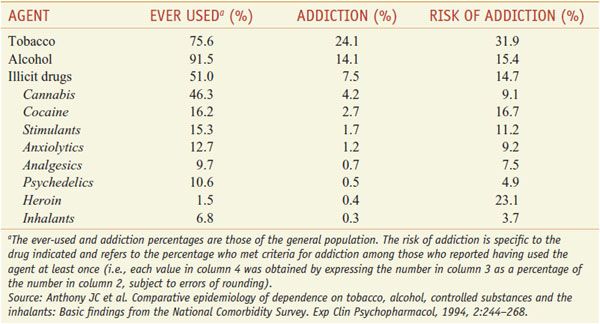

The abuse liability of a drug is enhanced by rapidity of onset. When coca leaves are chewed, cocaine is absorbed slowly and this produces low cocaine levels in the blood and few, if any, behavior problems. Crack, sold illegally and at a low price ($1-3 per dose), is alkaloidal cocaine (free base) that can be readily vaporized by heating. Simply inhaling the vapors produces blood levels comparable to those resulting from intravenous cocaine owing to the large surface area for absorption into the pulmonary circulation following inhalation. Thus, inhalation of crack cocaine is much more addictive than chewing, drinking, or sniffing cocaine. The risk for developing addiction among those who try nicotine is about twice that for those who try cocaine (Table 24–2). This does not imply that the pharmacological addiction liability of nicotine is twice that of cocaine. Rather, there are other variables listed in the categories of host factors and environmental conditions that influence the development of addiction.

Table 24–2

Dependence among Users 1990–1992

HOST (USER) VARIABLES. Effects of drugs vary among individuals. Polymorphism of genes that encode enzymes involved in absorption, metabolism, and excretion and in receptor-mediated responses may contribute to the different degrees of reinforcement or euphoria observed among individuals (see Chapters 6 and 7). Innate tolerance to alcohol may represent a biological trait that contributes to the development of alcoholism (see Chapter 23). While innate tolerance increases vulnerability to alcoholism, impaired metabolism may protect against it (see Chapter 23). Similarly, individuals who inherit a gene associated with slow nicotine metabolism may experience unpleasant effects when beginning to smoke and reportedly have a lower probability of becoming nicotine dependent.

Psychiatric disorders constitute another category of host variables. People with anxiety, depression, insomnia, or even shyness may find that certain drugs give them relief. However, the apparent beneficial effects are transient, and repeated use of the drug may lead to tolerance and eventually compulsive, uncontrolled drug use. While psychiatric symptoms are seen commonly in drug abusers presenting for treatment, most of these symptoms begin after the person starts abusing drugs. Thus, drugs of abuse appear to produce more psychiatric symptoms than they relieve.

ENVIRONMENTAL VARIABLES. Initiating and continuing illegal drug use is influenced significantly by societal norms and peer pressure.

PHARMACOLOGICAL PHENOMENA

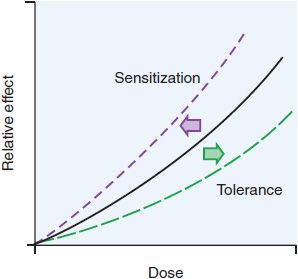

TOLERANCE. Tolerance, the most common response to repetitive use of the same drug, can be defined as the reduction in response to the drug after repeated administrations. Figure 24–1 shows an idealized dose-response curve for an administered drug. As the dose of the drug increases, the observed effect of the drug increases. With repeated use of the drug, however, the curve shifts to the right (tolerance). There are many forms of tolerance likely arising through multiple mechanisms.

Figure 24–1 Shifts in a dose-response curve with tolerance and sensitization. With tolerance, there is a shift of the curve to the right such that doses higher than initial doses are required to achieve the same effects. With sensitization, there is a leftward shift of the curve such that for a given dose, there is a greater effect than seen after the initial dose.

Tolerance to some drug effects develops much more rapidly than to other effects of the same drug. For example, tolerance develops rapidly to the euphoria produced by opioids such as heroin, and addicts tend to increase their dose in order to reexperience that elusive “high.” In contrast, tolerance to the GI effects of opioids develops more slowly. The discrepancy between tolerance to euphorigenic effects (rapid) and tolerance to effects on vital functions (slow), such as respiration and blood pressure, can lead to potentially fatal overdoses.

Innate tolerance refers to genetically determined lack of sensitivity to a drug that is observed the first time that the drug is administered. Acquired tolerance can be divided into 3 major types: pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and learned tolerance, and includes acute, reverse, and cross-tolerance. Pharmacokinetic or dispositional tolerance refers to changes in the distribution or metabolism of a drug after repeated administrations such that a given dose produces a lower blood concentration than the same dose did on initial exposure. The most common mechanism is an increase in the rate of metabolism of the drug. For example, barbiturates stimulate the production of higher levels of hepatic CYPs, causing more rapid removal and breakdown of barbiturates from the circulation.

Pharmacodynamic tolerance refers to adaptive changes that have taken place within systems affected by the drug so that response to a given concentration of the drug is reduced. Examples include drug-induced changes in receptor density or efficiency of receptor coupling to signal-transduction pathways (see Chapter 3). Learned tolerance refers to a reduction in the effects of a drug due to compensatory mechanisms that are acquired by past experiences. One type of learned tolerance is called behavioral tolerance. A common example is learning to walk a straight line despite the motor impairment produced by alcohol intoxication. At higher levels of intoxication, behavioral tolerance is overcome, and the deficits are obvious.

Conditioned tolerance (situation-specific tolerance) develops when environmental cues or situations consistently are paired with the administration of a drug. When a drug affects homeostatic balance by producing sedation and changes in blood pressure, pulse rate, gut activity, and so on, there is usually a reflexive counteraction or adaptation in the direction of maintaining the status quo. If a drug always is taken in the presence of specific environmental cues (e.g., smell of drug preparation and sight of syringe), these cues begin to predict the effects of the drug, and the adaptations begin to occur, which will prevent the full manifestation of the drug’s effects (i.e., cause tolerance). This mechanism follows classical (pavlovian) principles of learning and results in drug tolerance under circumstances where the drug is “expected.”

Acute tolerance refers to rapid tolerance developing with repeated use on a single occasion, such as in a “binge.” For example, repeated doses of cocaine over several hours produce a decrease in response to subsequent doses of cocaine during the binge. This is the opposite of sensitization, observed with an intermittent dosing schedule. Sensitization or reverse tolerance refers to an increase in response with repetition of the same dose of the drug. Sensitization results in a shift to the left of the dose-response curve (see Figure 24–1). Sensitization, in contrast to acute tolerance during a binge, requires a longer interval between doses, usually ~1 day. Sensitization can occur with stimulants such as cocaine or amphetamine. Cross-tolerance occurs when repeated use of a drug in a given category confers tolerance not only to that drug but also to other drugs in the same structural and mechanistic category. Understanding cross-tolerance is important in the medical management of persons dependent on any drug.

Detoxification is a form of treatment for drug dependence that involves giving gradually decreasing doses of the drug to prevent withdrawal symptoms, thereby weaning the patient from the drug of dependence. Detoxification can be accomplished with any medication in the same category as the initial drug of dependence. For example, users of heroin also are tolerant to other opioids. Thus, the detoxification of heroin-dependent patients can be accomplished with any medication that activates opioid receptors.

PHYSICAL DEPENDENCE. Physical dependence is a state that develops as a result of the adaptation (tolerance) produced by a resetting of homeostatic mechanisms in response to repeated drug use. A person in this adapted or physically dependent state requires continued administration of the drug to maintain normal function. If administration of the drug is stopped abruptly, there is another imbalance, and the affected systems must readjust to a new equilibrium without the drug.

WITHDRAWAL SYNDROME. The appearance of a withdrawal syndrome when administration of the drug is terminated is the only actual evidence of physical dependence. Withdrawal signs and symptoms occur when drug administration in a physically dependent person is terminated abruptly. Withdrawal symptoms have at least 2 origins:

• Removal of the drug of dependence

• CNS hyperarousal owing to readaptation to the absence of the drug of dependence

Pharmacokinetic variables are of considerable importance in the amplitude and duration of the withdrawal syndrome. Withdrawal symptoms are characteristic for a given category of drugs and tend to be opposite to the original effects produced by the drug before tolerance developed. Tolerance, physical dependence, and withdrawal are all biological phenomena. They are the natural consequences of drug use and can be produced in experimental animals and in any human being who takes certain medications repeatedly. These symptoms in themselves do not imply that the individual is involved in misuse or addiction. Patients who take medicine for appropriate medical indications and in correct dosages still may show tolerance, physical dependence, and withdrawal symptoms if the drug is stopped abruptly rather than gradually.

CLINICAL ISSUES

Abuse of combinations of drugs is common. Alcohol is so widely available that it is combined with practically all other categories. Some combinations reportedly are taken because of their interactive effects. When confronted with a patient exhibiting signs of overdose or withdrawal, the physician must be aware of these possible combinations because each drug may require specific treatment.

CNS DEPRESSANTS

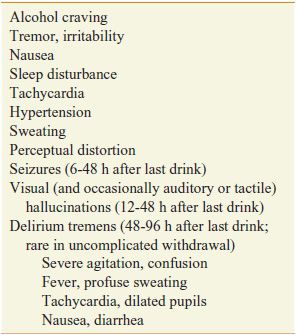

ETHANOL. More than 90% of American adults report experience with ethanol (commonly called “alcohol”). Ethanol is classified as a depressant because it produces sedation and sleep. However, the initial effects of alcohol, particularly at lower doses, often are perceived as stimulation owing to a suppression of inhibitory systems (see Chapter 23). Heavy use of ethanol causes development of tolerance and physical dependence sufficient to define an alcohol withdrawal syndrome (Table 24–3).

Table 24–3

Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome

Tolerance, Physical Dependence, and Withdrawal. The symptoms of mild intoxication by alcohol vary among individuals. Some experience motor incoordination and sleepiness. Others initially become stimulated. As the blood level increases, the sedating effects increase, with eventual coma and death occurring at high alcohol levels. The innate tolerance to alcohol varies greatly among individuals and is related to family history of alcoholism. Experience with alcohol can produce greater tolerance (acquired tolerance) such that extremely high blood levels (300-400 mg/dL) can be found in alcoholics who do not appear grossly sedated. In these cases, the lethal dose does not increase proportionately to the sedating dose, and thus the margin of safety (therapeutic index) is decreased.

Heavy consumers of alcohol acquire tolerance and also develop a state of physical dependence. This often leads to drinking in the morning to restore blood alcohol levels diminished during the night. The alcohol-withdrawal syndrome generally depends on the size of the average daily dose and usually is “treated” by resumption of alcohol ingestion. Withdrawal symptoms are experienced frequently but usually are not severe or life-threatening until they occur in conjunction with other problems, such as infection, trauma, malnutrition, or electrolyte imbalance. In the setting of such complications, the syndrome of delirium tremens becomes likely.

Alcohol addiction produces cross-tolerance to other sedatives such as benzodiazepines. This tolerance is operative in abstinent alcoholics, but while the alcoholic is drinking, the sedating effects of alcohol add to those of other sedatives. This is particularly true for benzodiazepines, which are relatively safe in overdose when given alone but potentially are lethal in combination with alcohol. The chronic use of alcohol and other sedatives is associated with the development of depression and the risk of suicide. Cognitive deficits have been reported in alcoholics tested while sober. These deficits usually improve with abstinence. More severe recent memory impairment is associated with specific brain damage caused by nutritional deficiencies common in alcoholics (e.g., thiamine deficiency). Medical complications of alcohol abuse and dependence include liver disease, cardiovascular disease, endocrine and GI effects, and malnutrition, in addition to the CNS dysfunctions outlined earlier. Ethanol readily crosses the placental barrier, producing the fetal alcohol syndrome, a major cause of mental retardation (see Chapter 23).

Pharmacological Interventions

Detoxification. Although most mild cases of alcohol withdrawal never come to medical attention, severe cases require general evaluation; attention to hydration and electrolytes; vitamins, especially high-dose thiamine; and a sedating medication that has cross-tolerance with alcohol. To block or diminish the symptoms described in Table 24–3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree