Chapter 3 Disorders of keratinization

Ichthyosis

The term ichthyosis (Gr. ichthys, fish) is applied to a number of heterogenous genetic disorders characterized by permanent and generalized abnormal keratinization.1,2 The clinical features range from mild involvement, often passed off as ‘dry skin’ (xerosis), through to severe widespread scaly lesions causing much discomfort and social embarrassment (Fig. 3.1). The scales are often shed as clusters rather than as single cells as is the norm.1 The pathogenesis of the ichthyoses is very complex but ultimately depends upon two distinct final common pathways: one relates to retention of corneocytes (e.g., ichthyosis vulgaris, recessive X-linked ichthyosis), the other involves epidermal hyperproliferation (e.g., congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, bullous ichthyosis, Sjögren-Larsson syndrome and Refsum’s disease).3

Ichthyotic skin disorders are classified into the following groups3a (Tables 3.1, 3.2):

Table 3.1 Non-congenital ichthyoses

| Isolated (nonsyndromic ichthyosis) | With associated symptoms (syndromic ichthyosis) |

|---|---|

| Autosomal dominant ichthyosis vulgaris | Syndromes with steroid sulfatase deficiency |

| Recessive X-linked ichthyosis | Multiple sulfatase deficiency |

| Refsum’s disease |

Table 3.2 Congenital ichthyoses

| Isolated (nonsyndromic ichthyosis) | With associated symptoms (syndromic ichthyosis) |

|---|---|

| Autosomal recessive lamellar ichthyoses (nonbullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma) | Comèl-Netherton’s syndrome Sjögren-Larsson syndrome |

| Harlequin ichthyosis | Conradi-Hünermann-Happle syndrome (chondrodysplasia puncta type 2) |

| Autosomal dominant lamellar ichthyosis | Ichthyosis prematurity syndrome |

| Bullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma | Gaucher syndrome, Type 2 Dorfman-Chanarin syndrome |

| Ichthyosis bullosa of Siemens | Trichothiodystrophy |

| Peeling skin syndrome ichthyosis hystrix Curth-Macklin | Ichthyosis follicularis with atrichia and photophobia |

| Congenital reticular ichthyosiform erythroderma |

The development of a diffuse ichthyosis-like scaling during life should not be confused with ichthyotic skin disorders. These acquired ichthyosis-like (ichthyosiform) skin conditions can be caused by different underlying diseases (see below). 4

Ichthyosis vulgaris

Clinical features

This relatively common disorder (incidence of 1:250 to 1:1000 births) has an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance.1,2 It may present initially as keratosis pilaris (follicular hyperkeratosis) on the arms, buttocks and thighs. The disease is usually fairly mild and becomes apparent within the first few months or years of life. It affects the sexes equally and presents as dryness (xerosis) and slight to moderate fine scaling, particularly involving the extensor surfaces of arms and legs and characteristically sparing the flexures (Fig. 3.2). The light-gray scales vary in quality from thick adherent shiny plates to simply dusty accumulations which, when scratched, leave a mark just as when one touches a dusty surface. The truncal lesions tend to be thicker than those on the face and scalp. The rims of the ears are often scaly.3 There is seasonal variation, with improvement of the condition in the summer months, particularly in humid climates.2 The palms and soles show increased palmar and plantar markings in contradistinction to sex-linked ichthyosis and may also show mild hyperkeratosis.3 An association with keratosis punctata of the palms and soles has also been documented.4 Chapping of the hands and feet can be a problem.5 There is no evidence of hair, nail, or teeth involvement. There is an increased incidence of atopic disorders.5 Serum lipids are normal.3

Pathogenesis and histological features

Ichthyosis vulgaris is characterized by deficiency of profilaggrin, a major constituent of the keratohyalin granules.6,7 Flaky tail mice, which represent an animal model of ichthyosis vulgaris, produce defective profilaggrin with resultant absence of filaggrin.8 Ultrastructurally, the keratohyalin granules are reduced, spongy or crumbly and associated with decreased amounts of filaggrin.9 The clinical severity of ichthyosis vulgaris correlates with the reduction of keratohyalin granules, which reflects a defective epidermal synthesis of filaggrin. Using fluorescein-labeled filaggrin antibodies demonstrates the severity of the defect (H. Traupe and V. Oji, unpublished observation). Filaggrin aggregates keratin intermediate filaments in the lower stratum corneum and is subsequently proteolyzed to form free amino acids including urocanic and pyrrolidone carboxylic acids critical as water-binding compounds in the stratum corneum.

Linkage analysis of the epidermal differentiation complex on chromosome 1q21 has identified mutations in the gene encoding filaggrin. Parents with one heterozygous filaggrin mutation may be asymptomatic, whereas affected offspring with two mutations often show classic ichthyosis vulgaris.10 Since the filaggrin gene is a major susceptibility gene for atopic dermatitis, mutations have also been shown in atopic dermatitis.11

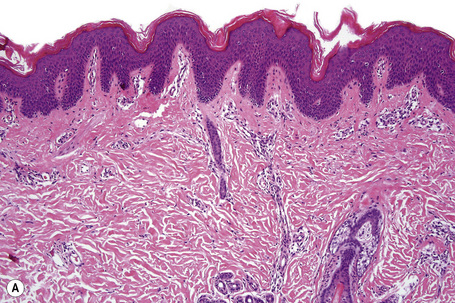

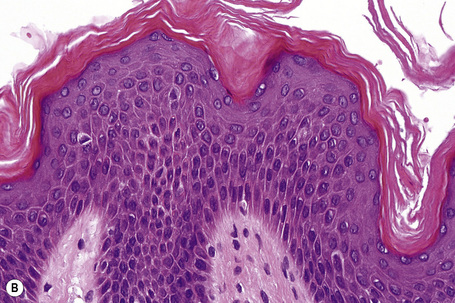

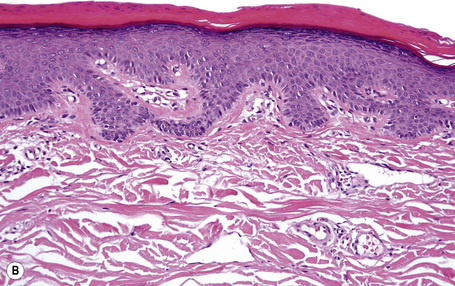

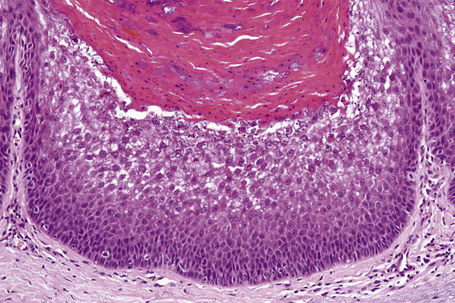

Ichthyosis vulgaris is characterized by mild to moderate orthohyperkeratosis associated with a hyperplastic, atrophic or normal epidermis. The key feature is a thin or absent granular cell layer (Fig. 3.3).12,13 Regional variation in the thickness and/or presence of the granular cell layer may be a feature and therefore it is best to take the biopsy from a site of maximal scaling. The lesions of keratosis pilaris show dilated follicles containing large keratin plugs. In the upper dermis a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate may be present. When ichthyosis vulgaris is associated with atopic dermatitis, parakeratosis and other signs of a spongiotic dermatitis can be found.

Differential diagnosis

The histologic differential diagnosis includes other diseases characterized by orthohyperkeratosis and a reduced or absent stratum granulosum (Table 3.3)

Table 3.3 Histologic patterns in ichthyotic skin disorders

| Orthohyperkeratosis & stratum granulosum reduced or absent |

| Ichthyosis vulgaris (w/o atopic dermatitis) |

| Acquired ichthyosis-like condition |

| Refsum syndrome |

| Dorfman syndrome |

| Trichothiodystrophy syndrome |

| Conradi-Hünermann-Happle syndrome |

| Orthohyperkeratosis & stratum granulosum well developed |

| XR-ichthyosis |

| AR-lamellar ichthyosis |

| Harlequin ichthyosis |

| Acquired ichthyosis-like condition |

| (Lichen simplex chonicus) |

| Hyperkeratosis with ortho- and parakeratosis and stratum granulosum prominent |

| AD-lamellar ichthyosis |

| Sjögren-Larsson syndrome |

| Harlequin ichthyosis |

| Inflammatory skin disease |

| Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis |

| Bullous ichthyotic erythroderma Brocq |

| Annular epidermolytic ichthyosis |

| Ichthyosis bullosa Siemens |

| Epidermal nevi |

| Epidermolytic acanthoma/leukoplakia |

| Epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoses |

| Incidental finding |

| Perinuclear vacuoles and binucleated keratinocytes |

| With parakeratosis: Congenital reticular Ichthyosiform erythroderma |

| With orthokeratosis: Ichthyosis hystrix Curth-Macklin |

| Differential diagnosis: Epidermolytic ichthyoses (Keratin clumps !) |

| Follicular hyperkeratosis |

| Keratosis pilaris, lichen spinulosus, phrynoderma |

| Keratosis pilaris atrophicans |

| Ichthyosis vulgaris with follicular keratosis |

| Lamellar ichthyosis |

| Sjögren-Larsson syndrome |

| Ichthyosis follicularis with alopecia and photophobia |

| Congenital atrichia |

| HID-, KID syndrome |

| Hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia |

| Pachyonychia congenita |

| Ectodermal dysplasias |

| Darier’s disease |

| Pityriasis rubra pilaris |

| Psoriasis-like features |

| Psoriasis vulgaris |

| Dermatophytosis |

| Comèl-Netherton’s syndrome |

| Annular epidermolytic ichthyosis |

| CHILD syndrome |

| Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome |

X-linked recessive ichthyosis

Clinical features

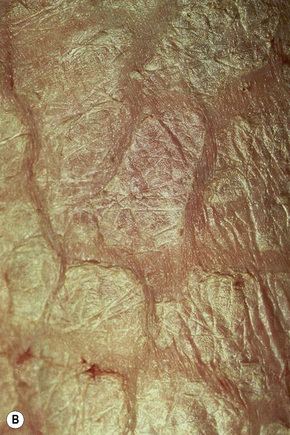

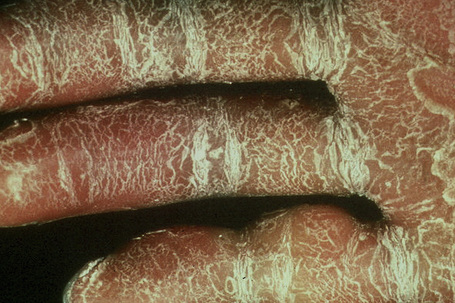

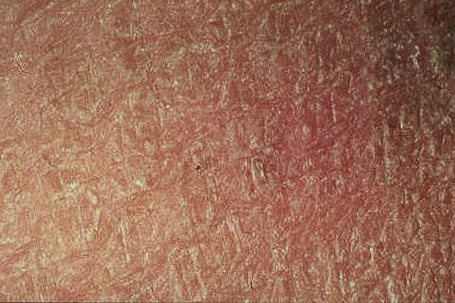

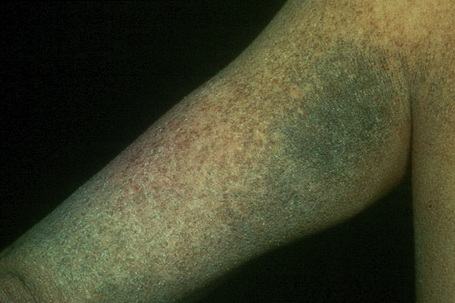

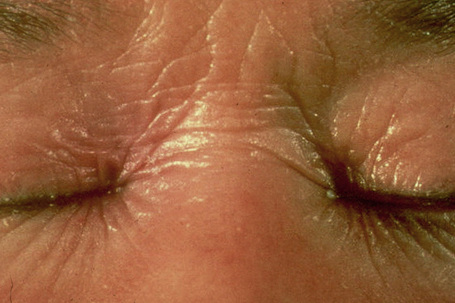

Also known as steroid sulfatase deficiency and ichthyosis nigricans, this X-linked, recessively inherited disorder has an incidence of 1:6000 male births.1–3 The disease is exceedingly rarely expressed in females.4 Cutaneous lesions tend to be more conspicuous and severe than in the autosomal dominant variant.2 The scales are large and dark and are seen particularly on the trunk, the extensor surface of the extremities, the scalp, the preauricular region, and the neck (Figs 3.4–3.7).2 Mild Involvement of the flexures is also present (Fig. 3.8).1 However, differentiation from ichthyosis vulgaris can be difficult as some patients present with fine, light scales and the flexures may be spared. The palms and soles are usually unaffected and keratosis pilaris is not a feature. Involvement of the trunk and neck often gives the skin a dirty appearance. Lesions may improve or disappear in warm weather.2 The hair, nails, and teeth are not affected.

Fig. 3.5 Sex-linked ichthyosis: the scale is coarser than that seen in ichthyosis vulgaris.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Fig. 3.6 Sex-linked ichthyosis: the scales are large and disfiguring.

By courtesy of R.A. Marsden, MD, St George’s Hospital, London, UK.

Fig. 3.8 Sex-linked ichthyosis: involvement of the flexures is sometimes a feature of this variant.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

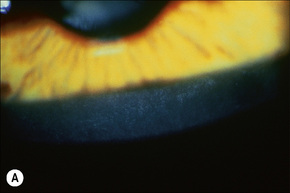

Corneal opacities due to comma-shaped deposits in the posterior capsule of Descemet’s membrane or corneal stroma, visible with slit-lamp examination (Fig 3.9), are characteristic and may be detected in female carriers.5 Inadequate cervical dilatation may lead to prolonged delivery of affected male newborns. Undescended testes and hypogonadism can be a feature in as many as 25% of affected patients.6–8 Rarely, testicular cancer has been documented.6

Pathogenesis and histological features

The disease is associated with a deficiency of the microsomal enzyme, steroid sulfatase/STS (sterol sulfate sulfohydrolase/arylsulphatase C).9 This is a membrane-bound enzyme, which hydrolyses the 3-β-sulfate esters of cholesterol and the sulfated steroid hormones.10 Absence of this enzyme is associated with persistence of the sulfate moiety on a number of sulfated steroid hormones and cholesterol sulfate.3

X-linked recessive ichthyosis is characterized by a raised serum cholesterol sulfate.10 The corneocytes contain excess cholesterol 3-sulfate and diminished free sterol.11 Steroid sulfatase deficiency possibly results therefore in persistence of the lipid contents of the membrane-coating granules and hence increased or persistent adhesion between adjacent keratin plates in the stratum corneum. Beyond that, increased amounts of cholesterol sulfate may inhibit the epidermal serine protease activity, which results in retention of corneodesmosomes leading to less shedding of scales and retention hyperkeratosis. Steroid sulfatase deficiency can be detected using the patient’s peripheral leukocytes and cultured skin fibroblasts. Diagnosis may also be affected by lipoprotein electrophoresis, which shows increased mobility of low density and very low density beta-lipoproteins in addition to the steroid sulfatase deficiency.12,13

The gene locus for recessive X-linked ichthyosis is within the Xp22.3 region of the X chromosome.14–16 Recently, indirect genotypic analysis using polymorphic DNA markers closely linked to the STS gene has been shown to be a reliable method of detection of the carrier status.14,17 Complete deletions of structural STS gene have been reported in 90% of patients with X-linked ichthyosis;14,16–19 the other 10% show partial deletions or point mutations.1 Carrier status can also be confirmed by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis.19 Recently, rapid diagnosis and differentiation from ichthyosis vulgaris using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has been documented.20 Other important genes are located close to the steroid sulfatase gene.

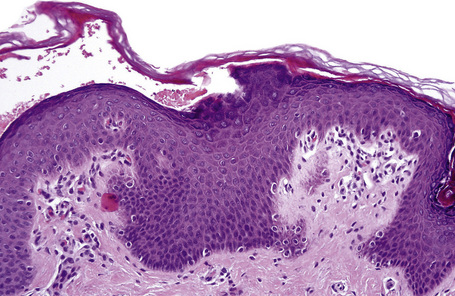

Lesions show non-specific features of compact hyperkeratosis and slight acanthosis associated with a granular cell layer, which may be normal or increased in thickness (Fig. 3.10).21,22 Keratohyalin granules show no abnormality. Follicular plugging is not a feature. Paradoxically, biopsies of thicker scales can show massive orthohyperkeratosis with reduction of the granular layer and a thin epidermis, causing confusion with ichthyosis vulgaris. A discrete lymphocytic perivascular inflammatory cell infiltrate may be evident.

Ultrastructural features include a high number of transitional cells and an abnormal persistence of desmosomal disks in the horny layer while keratohyalin granules are normal. An increased melanosome transfer accounts for the dark appareance of the scales.23

Syndromes with steroid sulfatase deficiency

A number of other important genes are located close to the steroid sulfatase gene. If a deletion is larger, it may include some of these genes, producing a contiguous gene syndrome.1 Two closely linked genes are those for Kallmann syndrome (hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and anosmia) and X-linked recessive chondrodysplasia punctata.2 Possible linkage to a gene for hypertrophic pyloric stenosis has also been described.2 Thus patients may present with the skin changes of X-linked recessive ichthyosis but with a whole spectrum of other problems.2

Multiple sulfatase deficiency

Multiple sulfatase deficiency is a severe neuropediatric disorder inherited as an autosomal recessive. Patients develop normally for the first several years and then begin to show striking loss of mental capacity and motor abilities. They usually die before puberty. The ichthyosis is typically mild and the least of their problems. In multiple sulfatase deficiency patients the ichthyosis is similar to but usually less severe than in X-linked recessive ichthyosis. Therefore, ichthyosis in a child with unexplained neurological symptoms should always prompt measurement of steroid sulfatase levels.1

Refsum syndrome

Clinical features

Refsum syndrome (hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy type 4, heredopathica atactica polyneuritiformis, phytanic acid deficiency) is a rare type of an autosomal recessive syndromic ichthyosis.1 The skin changes appear in childhood and are similar to those seen in ichthyosis vulgaris including hyperlinear palms. Due to lipid storage, melanocytic nevi may show a yellow hue. Associated symptoms include loss of vision from retinitis pigmentosa, in which night blindness is often the first problem, anosmia, cardiac arrhythmias, and a whole spectrum of neurological problems including bilateral sensorineural deafness, cerebellar ataxia, and peripheral polyneuropathies.2

Pathogenesis and histological features

Refsum syndrome is generally caused by a mutation in a gene encoding perioxisomal phytanol-CoA hydroxylase, although it can also be caused by specific mutations in the peroxisomal receptor gene PEX7.3,4 Peroxisomes are involved in the metabolism of bile acid and cholesterol biosynthesis. Elevated levels of phytanic acid in plasma and tissue are diagnostic. Low-phytol diet is mandatory.5

Routine histology of a skin biopsy does not differ from ichthyosis vulgaris. When a biopsy is fixed in alcohol and a Sudan stain performed, lipid droplets are found in the keratinocytes, in particular in biopsies from melanocytic nevi. The same inclusions can be shown by ultrastructural examination.6

Autosomal recessive lamellar ichthyoses

Clinical features

Autosomal recessive lamellar ichthyoses include a group of mostly monogenetic disorders presenting at birth with generalized hyperkeratosis and scaling (ichthyosis congenita). The clinical presentation varies considerably in severity and clinical course.1–5

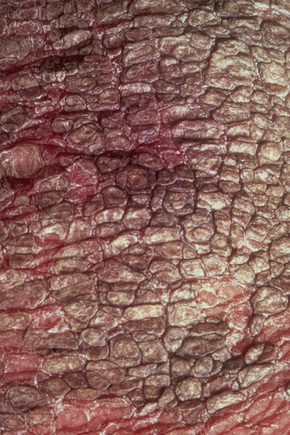

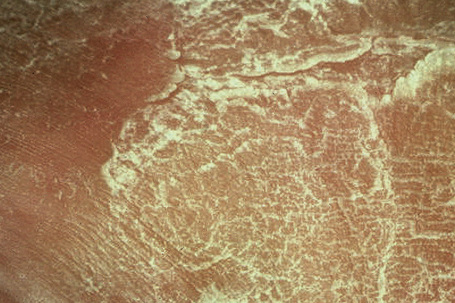

The more severe noneyrthrodermic phenotype of lamellar ichthyosis has an estimated prevalence of 1:200 000–300 000. The infant is often born encased in a thick ‘collodion’ plate-like shell of keratin (Figs 3.11, 3.12), and while the term ‘collodion baby’ is most often applied to cases of lamellar ichthyosis, similar appearances are sometimes found in a number of other disorders such as autosomal dominant lamellar ichthyosis, Netherton’s syndrome, Sjögren-Larsson syndrome, trichothiodystrophy, and infantile cerebral Gaucher syndrome.3,4 Hence, colloidon baby is a clinical description but not a disease. Within a few days the shell is shed to reveal a mild erythroderma with generalized scaling (Fig. 3.13). In nonerythrodermic phenotype of lamellar ichthyosis the scales are large, dark and platelike and cover the entire body including the palms, soles, scalp, and flexures.5–8 Fissuring of the hands and feet occurs and the skin around the joints may become verrucous. There is often associated difficulty with sweating, and hyperpyrexia may be a feature.7 There is nail dystrophy, hair involvement (scarring alopecia), severe ectropion (up to 80% of patients) and eclabium are characteristic (Fig. 3.14). The ectropion is of the cicatricial type and develops as a consequence of excessive dryness and associated contracture of the anterior lamella of the eyelid. Complications include corneal ulceration, vascularization, and corneal scarring with eventual blindness.9 Primary conjunctival lesions have also been described including ichthyosis, keratinization, hyper- and parakeratosis, and papilla development. The teeth are not affected.3

Fig. 3.13 Autosomal recessive lamellar ichthyosis: note the widespread and prominent large dark brown scales.

By courtesy of D. Atherton, MD, Children’s Hospital at Great Ormond Street, London, UK.

Fig. 3.14 Autosomal recessive lamellar ichthyosis: in this infant, there is gross ectropion and eclabion.

By courtesy of D. Atherton, MD, Children’s Hospital at Great Ormond Street, London, UK.

In contrast, other individuals show a more pronounced erythroderma with fine, white scaling (non-bullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, NCIE). A collodion membrane is often present at birth.1 After shedding, the infant typically presents with an intense generalized erythroderma.2 While platelike scales may be seen on the extensor surfaces of the legs, the scalp, face, upper extremities and trunk are covered with fine white scaling (Figs 3.15–3.00800).8 Mild ectropion and eclabium may be complications and palmoplantar keratoderma is often more severe than in noneyrthrodermic forms of AR-lamellar ichthyosis.3 Exceptionally, congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma has been associated with retinitis pigmentosa.10 There is an increased risk of developing skin cancer including basal and squamous cell carcinoma.11

Fig. 3.17 Nonbullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma: there is intensive erythema and fine scaling.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Fig. 3.18 Nonbullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma: there is generalized platelike scaling.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Fig. 3.19 Nonbullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma: the scales are large, thick and white.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Pathogenesis and histological features

The most common cause of lamellar ichthyosis is transglutaminase-1 deficiency which accounts for 30–40% of cases. Mutations in the transglutaminase-1gene result in markedly diminished or lost enzyme activity and/or protein. In some cases, this enzyme is present but there is little detectable activity, and in other clinically similar cases, transglutaminase-1 levels appear to be normal.12–17 Since conventional enzyme assays and mutational analyses are tedious, an assay for the rapid screening of transglutaminase-1 activity using covalent incorporation of biotinylated substrate peptides into skin cryostat sections has been developed.18 Coupled with immunohistochemical assays using transglutaminase-1 antibodies, this allows rapid identification of those cases caused by alterations in this enzyme.18

Other variants of transglutaminase mutations are characterized by distinct clinical features. In self-healing collodion baby the transglutaminase-1 mutation is pressure-sensitive so that while in utero the enzyme cannot function properly, it resumes normal function after birth. About 10% of collodion babies fall into this group.19 In bathing suit ichthyosis (BSI) the mutation in transglutaminase-1 appears to be temperature sensitive so that the face and extremities are almost completely spared apart from skin areas overlaying blood vesssls. Digital thermography has validated a striking correlation between warmer body areas and the presence of scaling, suggesting a decisive influence of the skin temperature. In situ TGase testing in skin of BSI patients has also demonstrated a marked decrease of enzyme activity when the temperature is increased from 25 to 37 degrees Celsius.20

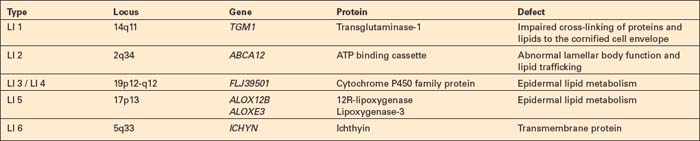

The second most common mutation in lamellar ichthyosis can be found in the binding cassette protein.21,22 Missense mutations cause lamellar ichthyosis while deletions are responsible for the far more dramatic harlequin fetus.23 Mutations in either transglutaminase-1 or the lipoxygenases are most often responsible for the nonbullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma phenotype. The ichthyin mutation also usually produces nonbullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma (Table 3.4).24–28 Attempts to refine the classification of non erythrodermic and erythrodermic phenotypes by the use of clinical, biochemical, and ultrastructural observations have so far failed to yield a consistent scheme.29–31 This difficulty is illustrated by the fact that the same transglutaminase-1 mutation can give rise to different phenotypes.31

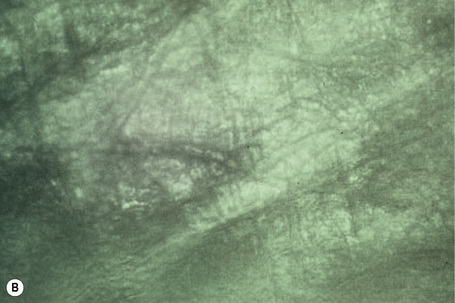

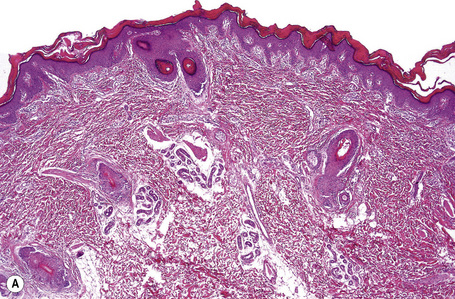

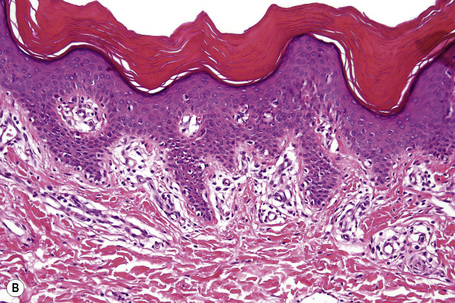

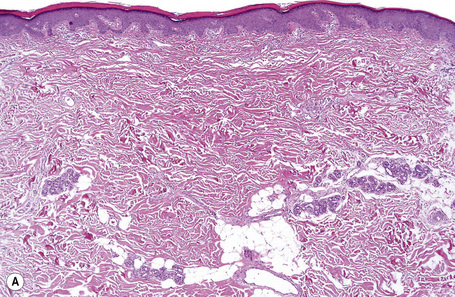

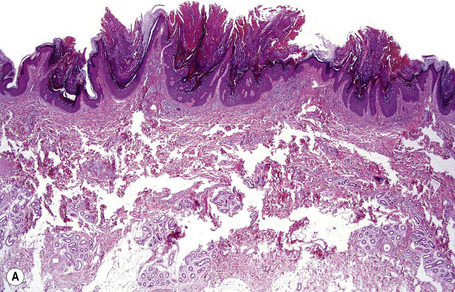

Histologically, the epidermis in autosomal recessive lamellar ichthyosis shows marked hyperkeratosis (which may be extreme in the collodion baby) and mild acanthosis with a normal or thickened granular cell layer (Fig. 3.21). The hyperkeratosis is much less marked in erythrodermic than in nonerythrodermic forms. Epidermal papillomatosis associated with a psoriasiform appearance has also been documented. A perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate is occasionally a feature.4 Dilatation and tortuosity of the dermal capillaries is sometimes evident. Follicular hyperkeratosis may occasionally be seen.

Ultrastructural studies show a variety of features including defective development of the cornified cell envelopes and electron-dense debris adjacent to the plasma membranes, cholesterol clefts, lipid vacuoles, increased numbers of small and dysmorphic lamellar bodies, elongated membrane structures, or membrane packages.32–34 Prenatal diagnosis of lamellar ichthyosis can be achieved by fetoscopy and biopsy.35

Harlequin ichthyosis

Clinical features

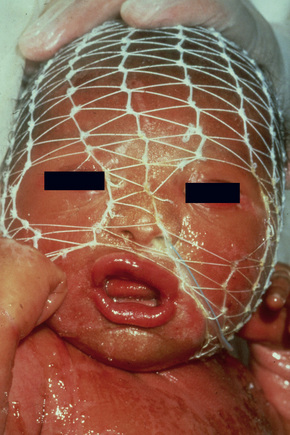

Harlequin ichthyosis (harlequin fetus, ichthyosis fetalis, ichthyosis congenita gravis) is an extreme and rapidly fatal subtype, where babies are born with a fissured ‘armor-plated’ skin (Fig. 3.22).1–4 Ectropion and eclabium are frequent complications, and the ears and nose are often malformed.2 Harlequin fetus has a very high mortality due to respiratory and feeding difficulties accompanied by excessive fluid loss.3 Sometimes, treatment by retinoids and intensive care is successful. Long-term survivors, following shedding of the scales, develop a severe erythroderma reminiscent of nonbullous ichthyosiform erythroderma.5 Fortunately, antenatal diagnosis is possible.6,7

Pathogenesis and histological features

This very rare form of ichthyosis is due to an apparently dramatic loss of function of the lamellar bodies, which results from nonsense mutations in the ABCA12 gene. Less severe missense mutations cause a variant of lamellar ichthyosis. This indicates that a severely truncated protein is the molecular cause of Harlequin ichthyosis.8 The ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family encompasses a variety of membrane proteins involved in the energy-dependent transport across membranes. In the epidermis, ABCA12 may have an important function for the lamellar bodies, through exocytosis traffic of lipids or proteases across the apical keratinocyte membrane.

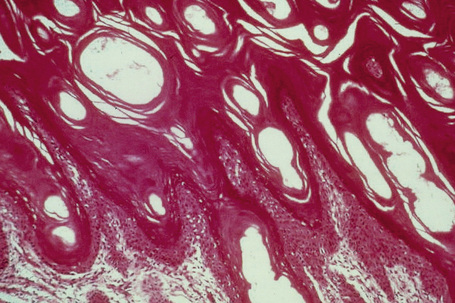

The lesions are characterized by massive hyperkeratosis (sometimes with lipid deposits) associated with a normal or absent granular cell layer (Fig. 3.23). The hair follicles are usually affected first, during the second trimester.2,7 Parakeratosis may also sometimes be evident.9 Acanthosis is often marked and papillomatosis is sometimes a feature. A sparse mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate can be present in the superficial dermis.7

Ultrastructurally, the harlequin fetus has recently been shown to be associated with deficient or morphologically abnormal lamellar bodies (including concentrically lamellated forms) and deficient intercellular lipid lamellae within the stratum corneum.1,2,9 Small vesicles, devoid of internal lamellation, may be present in the granular cell layer (and retained in the stratum corneum), but show no association with the keratinocyte cell membranes as is typical of normal lamellar bodies.1,9 Recent immunohistochemical evidence suggests that these vesicles represent abnormal lamellar bodies characterized by an inability to discharge their lipid contents into the intercellular space. Keratin and filaggrin expression have also been shown to be defective.2 In the harlequin fetus, the keratinocytes may display the hyperproliferative keratins K6 and K16 and show an inability to convert profilaggrin to filaggrin.2 The results of ultrastructural and biochemical analyses suggest that the harlequin fetus is a heterogeneous condition.

Autosomal dominant lamellar ichthyosis

Clinical features

Autosomal dominant lamellar ichthyosis is characterized by generalized scaling with palmoplantar keratoderma.1 Patients may present as a collodion baby. They are later covered by diffuse dark-gray scales that involve all areas of the body but are most prominent on the extensor surfaces. Backs of the hands and feet are characterized by lichenification. There may be massive plantar hyperkeratosis with thick, yellow scales. The palms are usually only minimally involved and show accentuated markings.1

Pathogenesis and histological features

This disorder appears to be genetically and clinically heterogeneous and of variable penetrance. Its genetic defect has not been identified. Biochemically, an abnormal lipid profile has been detected in the scales.2

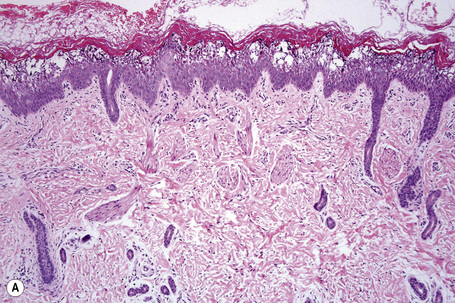

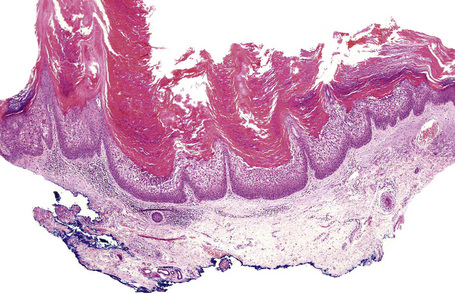

Histologically, there is an acanthosis, papillomatosis, and compact orthohyperkeratosis with focal parakeratosis that, paradoxically, is associated with a thickened stratum granulosum (Fig. 3.24).2

Electron microscopy shows a high number of transitional cells and a spongy appearance of the keratohyaline granules.2

Congenital bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma

Clinical features

Congenital bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma (also known as epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, bullous ichthyosis, bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma of Brocq) is a very rare disease (incidence of 1:300 000 births) and, although sometimes inherited by an autosomal dominant mode, it more often appears to arise by spontaneous mutation. At birth the infant may show marked hyperkeratosis, erythroderma, or even present as a collodion baby. Although the scales are soon lost, leaving a generalized moist, tender erythroderma, re-epithelialization leads to further scale production followed by the development of widespread blistering (Fig. 3.25) which heals without scarring. As the patient becomes older, the erythema and blistering become less apparent and, later, the disease is complicated by the development of verrucous hyperkeratosis, especially in the flexures (Figs 3.26–3.01350). In some cases, the scales have been said to assume a porcupine quill-like appearance (ichthyosis hystrix) and scalp involvement may simulate tinea capitis.1 The nape, axilla, groin, and flexural folds are sites of predilection. Occasional blisters still arise, often in summertime and at sites of pressure. In patients with keratin 1 but not with keratin 10 mutations, palmoplantar keratoderma is often present. Nail dystrophy may sometimes be a feature. The patients suffer from an offensive body odor. Congenital bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma is associated with considerable morbidity and significant mortality due to sepsis, fluid loss, and electrolyte imbalance.1

Fig. 3.28 Congenital bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma: same patient as Figure 3.27, showing elbow involvement.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Fig. 3.29 Congenital bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma: the hands are particularly affected.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Fig. 3.30 Congenital bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma: blistering may sometimes be seen in adulthood.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Fig. 3.31 Congenital bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma: adult showing very severe verrucous flexural scaling.

By courtesy of R.A.J. Eady, MD, Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

A nevoid variant in which the lesions follow Blaschko’s lines is also recognized.2 In the past, such lesions may have been mistaken for epidermal nevi showing epidermolytic hyperkeratosis. Due to the possibility of gonadal mutations, children of affected patients with the nevoid variant may develop generalized congenital bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma

An annular variant has also been described. Patients may have mild erythroderma and blisters at birth, but the characteristic feature is the presence of many annular gray hyperkeratotic plaques with a peripheral erythematous border. 3,4

Pathogenesis and histological features

There is considerable evidence in the recent literature confirming that congenital bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma represents a genetic disorder of keratin expression associated with hyperproliferation of the epidermis.5,6 In the skin, basal keratinocytes predominantly express keratin 5 and 14, while suprabasal cells switch to the expression of keratin 1 and 10. Keratin monomers form obligate heterodimers in pairs of acidic (type I) and basic (type II) keratins, which assemble into keratin intermediate filaments building a cytoskeleton for the structural stability and flexibility of epidermal cells. Transgenic mouse studies using a truncated human keratin 10 gene have been shown to result in the pathobiological and biochemical phenotype of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis.7 Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis shows linkage to the keratin gene cluster either on chromosome 12q11–13 (type II keratin) or chromosome 17q21-q22 (type I keratin).8–10 Direct sequencing of keratin 1 and 10 genes has identified point mutations in a number of affected families.11–17 Most mutations are missense and clustered at the ends of the central helical rod domains. Keratin 1 mutations are associated with severe palmoplantar hyperkeratosis while keratin 10 mutations are not because keratin 10 is physiologically substituted by keratin 9 on palmoplantar skin.15 Mutations in the keratin 1 or 10 gene exhibiting mosaicism explain the nevoid variant of congenital bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma.18,19 The annular variant shows minor mutations in keratin 1 or 10 genes on distinct keratin domains.4

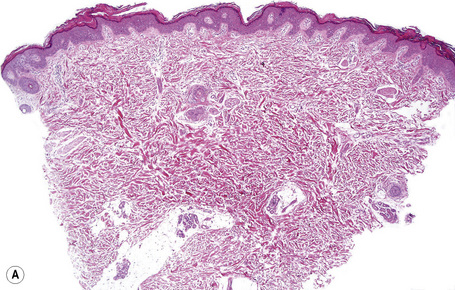

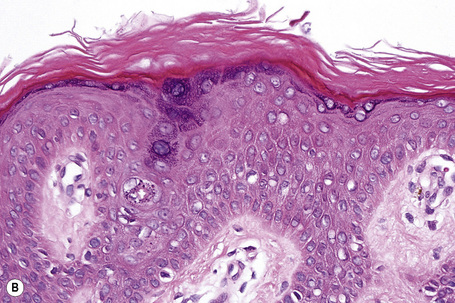

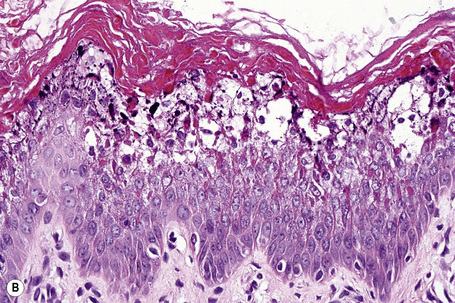

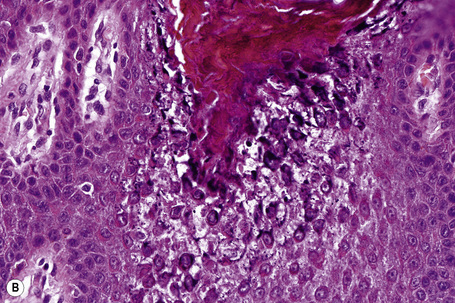

The histological features are known as epidermolytic hyperkeratosis or granular degeneration and are very striking.20,21 Suprabasal keratinocytes appear vacuolated and typically contain distinct eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions. The cell borders are ill defined and intraepidermal blister formation may be present. There is massive orthohyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis. The granular cell layer is prominent and contains coarse and irregular keratoyhaline granules (Fig. 3.32).

By immunohistochemistry, epidermolytic hyperkeratosis shows a normal distribution pattern of keratins 5/14 and 1/10, but in addition there is overexpression of keratin 14 in the suprabasal epithelium accompanied by quite marked labeling of the upper epithelial layers by keratin 16, as would be expected in a hyperproliferative state.5,22

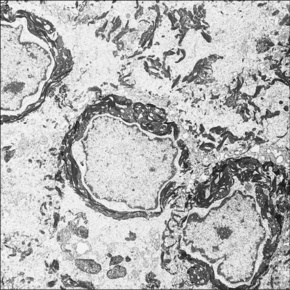

Ultrastructural studies have shown that the intracytoplasmic inclusions seen on light microscopy are composed of abnormally aggregated keratin filaments. Since large areas of the cytoplasm lack a regular keratin skeleton, the suprabasal keratinocytes appear vacuolated and contain irregular keratoyhaline granules. Impairment of desmosome-keratin complexes accounts for the fragility of the epidermis (Fig. 3.33).18 These ultrastructural changes may form the basis of prenatal diagnosis including amniotic fluid squame analysis.20,21

Fig. 3.33 Congenital bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma: striking perinuclear keratin clumping is evident.

By courtesy of R.A.J. Eady, MD, Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Immunoelectron microscopy has identified that the keratin clumps are composed of keratins 1 and 10.22

Differential diagnosis

Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis is a histopathologic pattern that is seen in many conditions including ichthyosis bullosa of Siemens, epidermal nevus, epidermolytic keratoderma, epidermolytic acanthoma, and epidermolytic leukoplakia (see Table 3.3). It may also represent an incidental finding in seborrheic keratosis, actinic keratosis, in situ squamous cell carcinoma, invasive squamous cell carcinoma, melanocytic nevi, and epidermal and pilar cysts.23 Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis may also be seen in normal and particularly actinically damaged skin. In such incidental lesions, the changes are limited to the epidermis overlying just one or two dermal papillae in contrast to the much more extensive involvement of the other conditions mentioned above. Therefore, accurate clinical information is necessary to avoid diagnostic confusion.

Ichthyosis bullosa of Siemens

Clinical features

Ichthyosis bullosa of Siemens is inherited as an autosomal dominant. The condition, which is milder than congenital bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma, presents at birth with blistering subsequently replaced by dark lichenified hyperkeratosis of the limbs, predominantly affecting the flexures and shins (Fig. 3.34).1,2 The skin remains fragile and blisters on mild trauma, giving rise to characteristic superficial peeling with a molting-like appearance (Mauserung phenomenon) (Fig. 3.35).2,3 Symptoms usually improve with age. Erythroderma is typically absent. Rarely, pustulation and hypertrichosis may be additional features.3,4 There is considerable clinical overlap between ichthyosis bullosa of Siemens and congenital bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma, and their distinction can best be achieved by molecular genetic analysis.

Fig. 3.34 Bullous ichthyosis Siemens: flexural hyperkeratosis with early blister formation.

By courtesy of W.A.D. Griffiths, MD, Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Pathogenesis and histological features

Bullous ichthyosis is associated with a point mutation in the keratin 2e gene on chromosome 12q11-q13.4–9 Since this keratin is not expressed on volar skin, palmoplantar keratoderma does not develop.

Histologically and by electron microscopy, the features are indistinguishable from congenital bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma except that they are milder and the vacuolation of the keratinocytes and cytoplasmic inclusions are restricted to the more superficial prickle and granular cell layers as opposed to involving almost the entire epidermis as is typical of the latter condition. Subcorneal separation may be evident.10

Linear epidermolytic epidermal nevus

Linear verrucous epidermal nevi occasionally show the features of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (Fig 3.36). Some patients with such a lesion, although by no means all, in reality suffer from the nevoid variant of congenital bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma.1–4 It is therefore important that patients with apparent epidermolytic epidermal nevi are offered genetic counseling.

Epidermolytic acanthoma

Clinical features

Isolated epidermolytic acanthoma (also termed disseminated epidermolytic acanthoma) is an acquired lesion that presents as a verrucous papule or plaque approximately 1.0 cm in diameter and sometimes resembles a viral wart, nevus or seborrheic keratosis.1–3 Lesions may present at any site, but the scrotum, head, neck, and leg are particularly affected.2,3 Although usually solitary, occasional patients may present with multiple localized or disseminated lesions.4–8 Variants affecting the mucosae of the oral cavity and female genital tract have also been documented.9,10 Caucasians and the Japanese are predominantly affected.3

Pathogenesis and histological features

Although not proven, it has been suggested that epidermolytic acanthoma develops as a consequence of keratin 1 and 10 gene mutation.3

The lesion is characterized by hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis (Fig. 3.37).1,2 The upper prickle cell and granular cell layers show features of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (i.e., marked vacuolation of the keratinocytes with eosinophilic keratin inclusions) (Fig. 3.38).

Epidermolytic acanthoma displays diminished expression of keratins 1 and 10 and increased expression of the hyperproliferative keratins 6 and 16.3

Differential diagnosis

Identical histological changes are seen in congenital bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma, linear epidermolytic epidermal nevus, epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma, and in focal epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (see Table 3.3). Clinical information is usually necessary to avoid diagnostic confusion.

Focal epidermolytic hyperkeratosis

Focal epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (incidental epidermolytic hyperkeratosis) represents a non-specific finding of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis in the epidermis overlying or adjacent to an unrelated lesion. It is very common and has been described, for example, in seborrheic keratoses, overlying scars and fibrous histiocytoma, in banal and dysplastic nevi, actinic keratosis, squamous cell carcinoma in situ, and melanoma. It may also be seen in normal skin. 1–5

Peeling skin syndrome

Clinical features

Peeling skin syndrome (familial continual skin peeling, keratolysis exfoliativa congenitale) is characterized by a spontaneous, lifelong peeling of the stratum corneum without bleeding or pain.1–6 The mode of inheritance is autosomal recessive.1 Three types can be distinguished:

Histological features

Ichthyosis hystrix Curth-Macklin

Clinical features

‘Ichthyosis hystrix’ is a descriptive name for cornification disorders with spiny and dark hyperkeratosis. Ichthyosis hystrix Curth-Macklin is characterised by generalized verrucous plaques, involving the entire trunk, the flexural surfaces of the extremities and the palms and soles. The autosomal dominant disorder sometimes resembles bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma, but there is no clinical or histological evidence for blistering. 1–3

Pathogenesis and histological features

Recent evidence suggests that in ichthyosis hystrix Curth-Macklin a mutation in a keratin gene affecting the variable tail domain (V2) of keratin 1 results in a failure in keratin intermediate filament bundling and retraction of the cytoskeleton from the nucleus.2 This is the first in vivo evidence for the crucial role of a keratin tail domain in supramolecular keratin intermediate filament organization and barrier formation.2

Histologically, the epidermis is acanthotic and orthohyperkeratotic. The suprabasal keratinocytes are vacuolated and a few of them appear binucleated. In contrast to epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions are not present.4

The significant ultrastructural observation in ichthyosis hystrix Curth-Macklin is the presence of perinuclear concentric shells of tonofilaments. In contrast to keratin mutations of the rod domain in epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, aggregations and clumping of keratin filaments are absent.4

Congenital reticular ichthyosiform erythroderma

Clinical features

Congenital reticular ichthyosiform erythroderma is a rare inherited disorder of keratinization.1 Since only sporadic cases have been recognized, the mode of inheritance is unknown. Most of the patients have been female. The patients are born with congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma. During childhood the integument clears gradually so that enlarging patches of normal skin appear to be enclosed by erythrokeratotic and hyperpigmented areas in a reticular arrangement. Because of this clinical appearance the genodermatosis has also been termed ichthyosis ‘en confettis’ or, more precisely, ichthyosis variegata.2–8 Associated features are hypertrichosis, and palmoplantar hyperkeratosis, and, in single cases, hypogonadism, growth retardation, hepatomegaly, keratoacanthoma or squamous cell carcinoma.1,5,7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree