(1)

Department of Pathology, Rutgers-New Jersey Medical School, Newark, NJ, USA

Keywords

Congenital anomalies, uterusMyometriumAdenomyosisLeiomyomaSymplastic leiomyomaIntravenous leiomyomatosisBenign metastasizing leiomyomaParasitic leiomyomaDiffuse peritoneal leiomyomatosisLeiomyosarcomaStromal noduleEndometrial stromal sarcoma7.1 Lesims of the Myometrium

Specimens received by pathology laboratories for myometrial pathology sometimes pose unique challenges (Table 7.1). Diseases of the myometrium are discussed in this chapter.

Table 7.1

Key points about myometrial pathology

The distinction between an endometrial stromal nodule and a low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma can rarely be made on a biopsy or curettage specimen and often necessitates hysterectomy |

Adenomyosis involved by adenocarcinoma should be reported, but does not factor into the measurement of tumor depth of invasion |

Confirmation of leiomyosarcoma requires consideration of additional factors besides mitotic count, including hemorrhage, lack of circumscription, atypia, and tumor cell necrosis. This may require many sections |

It may not be feasible to distinguish leiomyoma from leiomyosarcoma on frozen section |

7.2 Congenital Anomalies of the Uterus

The uterus is formed by fusion of the two Müllerian ducts and resorption of the resultant intervening septum. Anomalies are uncommon, but may include agenesis, dysgenesis, or varying types of duplication. Agenesis or dysgenesis may present as lack of onset of menses in adolescence. Lesions that are associated with obstruction to menstrual egress may present at menarche with symptoms of pain and an expanding mass, such as in duplication with a blind uterine horn. Lesions with menstrual egress may not show symptoms or may present with issues relating to fertility.

7.3 Benign Lesions of the Myometrium

7.3.1 Adenomyosis

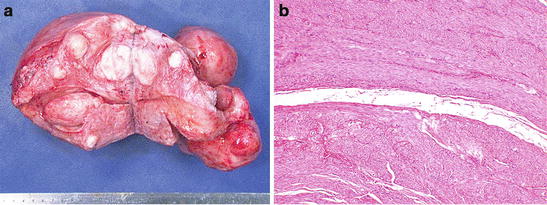

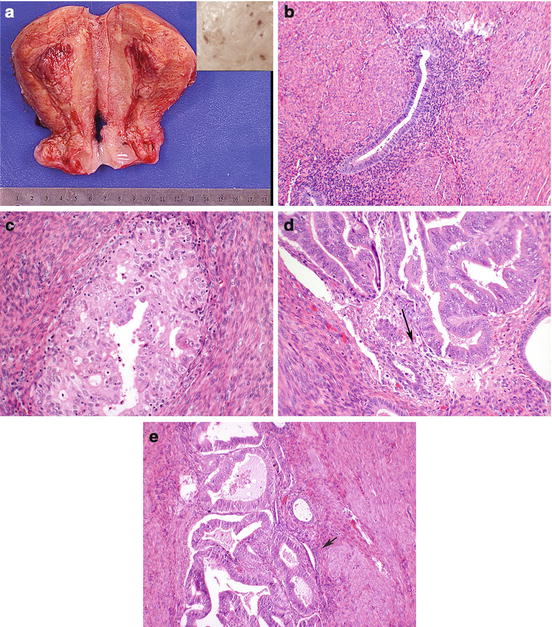

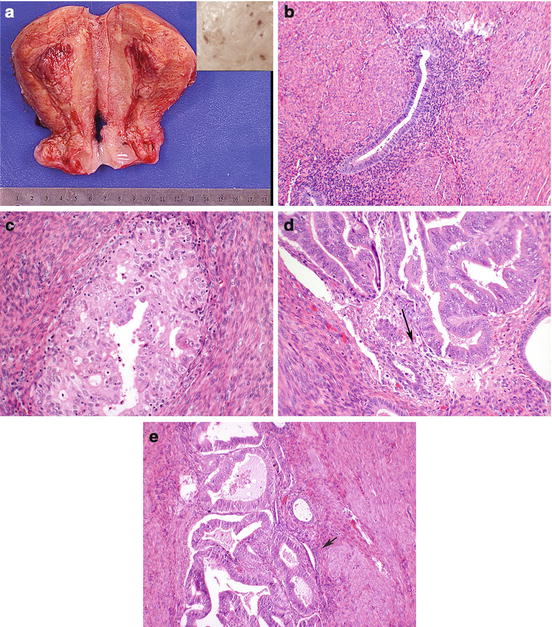

Adenomyosis is an extremely common finding in hysterectomy specimens. While the old name “endometriosis interna” referred to the nests of endometrial glands and stroma within the myometrium, which are required for histologic confirmation, the mechanism is thought to be totally different in adenomyosis than endometriosis. Adenomyosis is thought to connect with the surface endometrium [1], essentially representing diverticular outpouchings. Grossly, adenomyosis may markedly enlarge the uterus (Fig. 7.1a), although this enlargement is lacking in circumscription as seen in leiomyomata. On cut surface, small punctate bleeding sites are sometimes apparent in adenomyosis. Histology shows endometrial glands and stroma within the myometrium ((Fig. 7.1b). Occasionally, adenomyosis forms partially circumscribed nodules, “adenomyomas,” which may be clinically interpreted as leiomyomas, but which lack the well-defined pseudocapsule of leiomyomas, leading at times to increased operative blood loss when “myomectomy” is attempted and cleavage planes are less well-defined.

Fig. 7.1

Uterus diffusely enlarged by adenomyosis (a). Punctate areas may show hemorrhage (inset). Histologically the lesion is composed of endometrial glands and stroma within the myometrium (b). Endometrial carcinoma can involve adenomyosis, with features including rounded nests away from invading carcinoma (c), stroma seen amid the glands (d, arrow), and (e) benign glands (arrow) admixed with malignant serving as diagnostic clues

A potential pitfall for pathologists is distinguishing myometrial invasion of an endometrial adenocarcinoma from carcinomatous transformation of an adenomyotic focus, thought to be a field effect (Fig. 7.1c–e). Identification of stroma around the crowded atypical glands or residual benign glands is helpful, but immunohistochemistry may show overlapping features between carcinoma in adenomyosis and true myometrial invasion, limiting utility [2]. The depth of invasion of an endometrial carcinoma is measured to the deepest true invasion, not from tumor in adenomyotic foci, although these foci should be reported separately. It has been suggested that adenocarcinomatous transformation of adenomyotic foci is a risk factor for associated myometrial invasion [3].

7.3.2 Leiomyoma

Symptomatic leiomyomata are among the most common reasons for performance of a hysterectomy. Upon receipt of a hysterectomy for uterine fibroids, the specimen is weighted and the location of the fibroids described (submucous, intramural, subserosal) (Fig. 7.2a). The location may explain some of the symptomatology, with submucous fibroids more likely to cause abnormal uterine bleeding, and anterior subserosal or intramural large fibroids more likely to cause urinary symptoms, etc. Leiomyomas are well circumscribed, with a pseudocapsule. This is not a true capsule with a delineating membrane, but a compression of surrounding myometrium. This pseudocapsule (Fig. 7.2b) is what creates the surgical planes that permit ease of myomectomy. Histologically, leiomyomas usually resemble the adjacent uterine smooth muscle, with elongated cells with oval cigar-shaped nuclei (see Fig. 2.27). Leiomyomas have a tendency to outgrow their blood supply. They are estrogen-sensitive, and hence may grow rapidly in pregnancy and tend to regress in menopause. Degenerative changes of varying types may be seen. Some of these may raise both clinical and histopathological concern for leiomyosarcoma (see below). Benign degenerative changes that are commonly seen histologically and not likely to raise concern for the pathologist include hyalinization, with areas of acellular pink material and calcification.