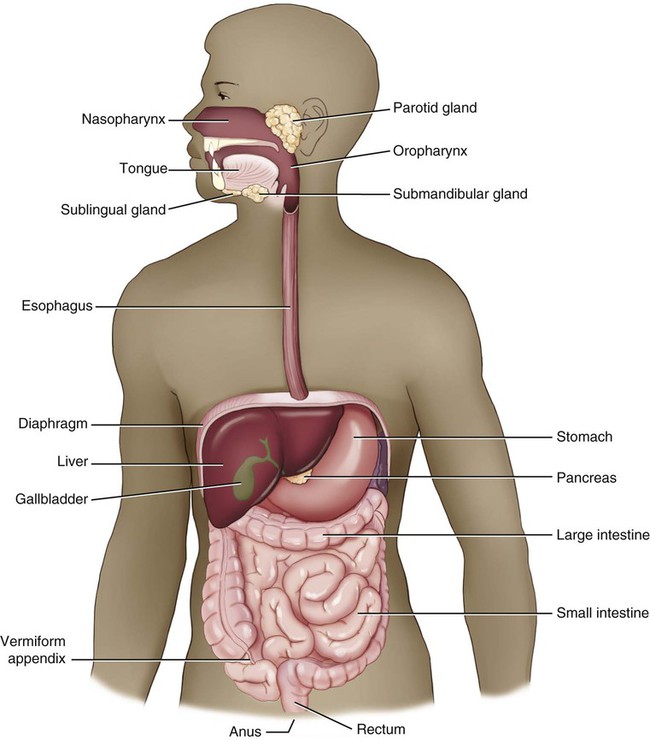

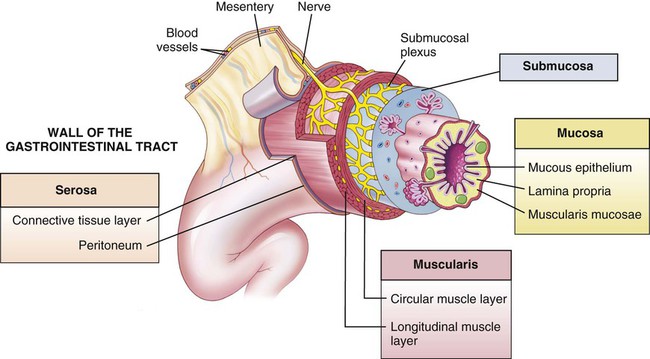

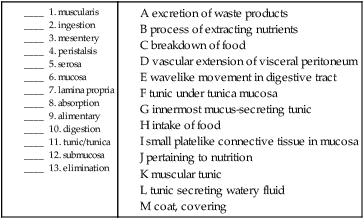

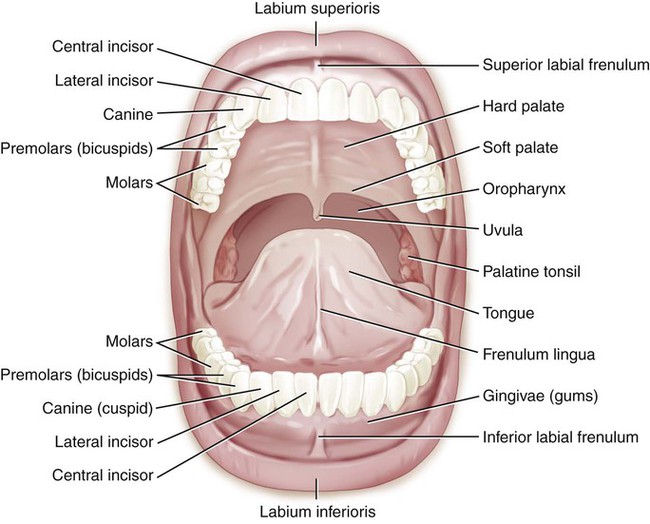

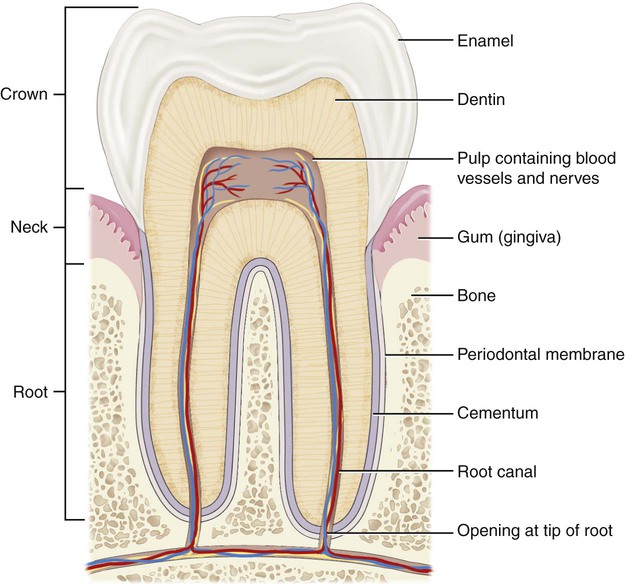

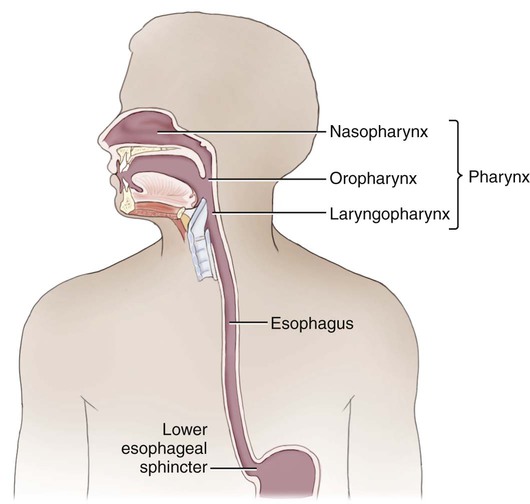

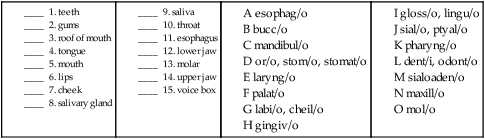

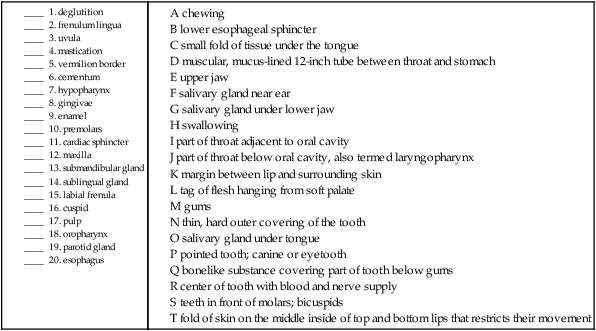

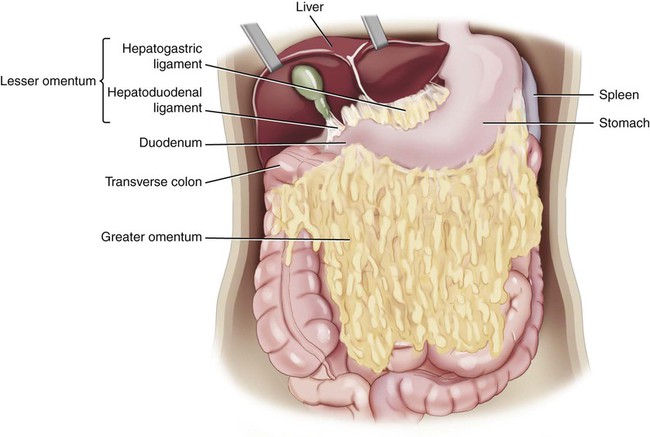

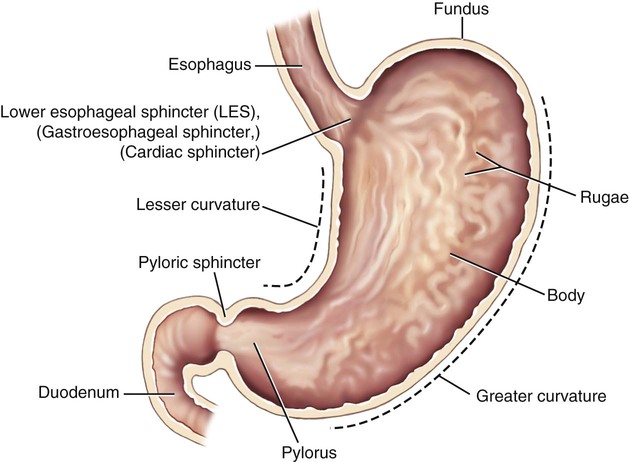

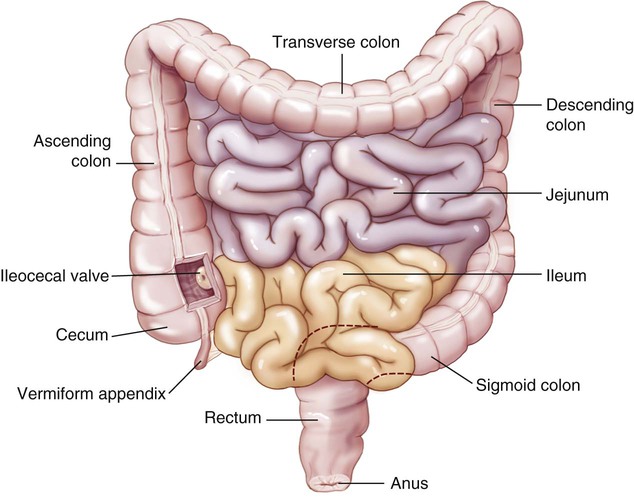

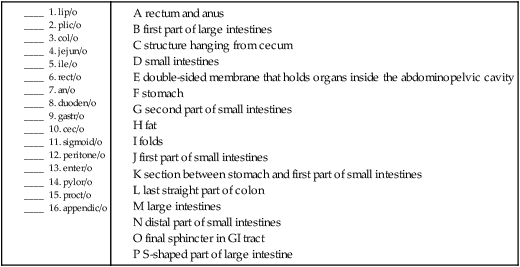

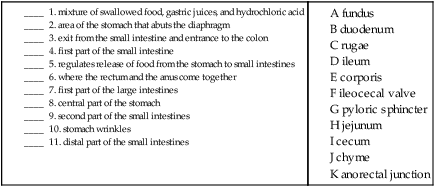

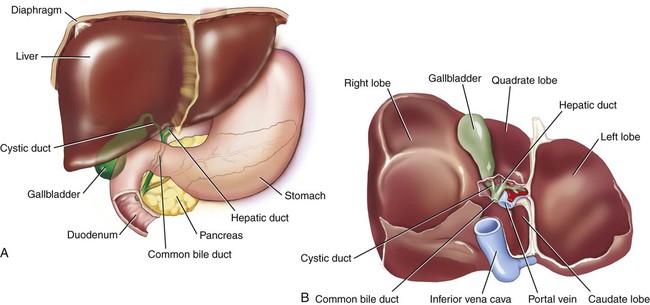

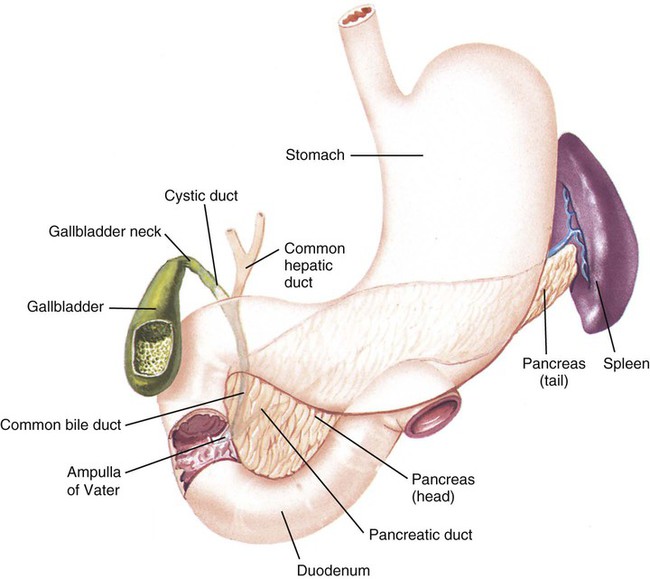

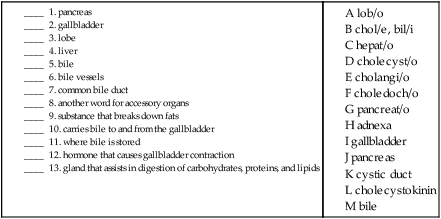

The digestive system (Fig. 5-1) provides the nutrients needed for cells to replicate themselves continually and build new tissue. This is done through several distinct processes: ingestion, the intake of food; digestion, the mechanical and chemical breakdown of food; absorption, the process of extracting nutrients; and elimination, the excretion of any waste products. Other names for this system are the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, which refers to the two main parts of the system (the stomach and intestines) and the alimentary canal, which refers to the function of the tubelike nature of the majority of the digestive system, which starts at the mouth and continues in varying diameters to the anus. Most of the alimentary canal is in four coats, or tunics: the mucosa, the submucosa, the muscularis, and the serosa (Fig. 5-2). The inner tunic is the mucosa, which secretes gastric juices, absorbs nutrients, and protects the tissue through the production of mucus, a thick, slimy emission. This membrane is lined with a single layer of epithelial tissue that is attached to a platelike layer of connective tissue, the lamina propria. You might want to note that the combining form lamin/o, used to mean a “thin plate,” appears throughout many body systems. The term propria is from Latin and means “one’s own, or special” and is most likely used to designate this particular lamina from the many others in the body. The submucosa, the tunic underneath the tunica mucosa, holds blood, lymphatic, and nervous tissues that nourish, protect, and communicate. The next tunic is the muscularis, two layers of circular and longitudinal muscles that contract and relax around the tube in a wavelike movement termed peristalsis. If peristalsis is absent or delayed, the movement of food through the tract is impaired, causing disorders like constipation. The outermost tunic has different names in the digestive system, depending on whether it occurs within or outside of the peritoneal cavity. If outside, an outer tunic covering that binds a structure together is called the adventitia (also tunica externa). The tunic within the peritoneal cavity that emits a slippery fluid to counteract friction is termed the serosa. The serosa and visceral peritoneum are synonymous. All of these four layers are then attached to the body wall in the peritoneum by a rich vascular membrane which is an extension of the visceral peritoneum termed the mesentery. Food normally enters the body through the mouth, or oral cavity (Fig. 5-3). The digestive function of this cavity is to break down the food mechanically by chewing (mastication) and lubricate the food to make swallowing (deglutition) easier. The upper and lower jaws (maxilla and mandible) hold approximately 32 permanent teeth that are set in the fleshy gums (gingivae) of the alveolar ridges of each bone. The thin, hard outer covering of the tooth is the enamel, while the dentin is the calcified second layer of the tooth (Fig. 5-4). The pulp is the center of the tooth with a blood and nerve supply. Cementum is a bonelike substance that covers the part of the tooth that is below the gums. The crown of the tooth is the visible enamel, the root is the area below the gums, and the neck is the area where both of these meet. The teeth are named by their function, location, or appearance. The central and lateral incisors are the front teeth that initially tear food to be chewed on the back teeth, the molars (derived from Latin for grinding). In between the incisors and the molars, the teeth are named for the number of points (cusps), either as cuspids or bicuspids (also called premolars because they are in front of the molars). Another name for the cuspids is the canines, because of the perceived similarity to the dentition of dogs. The upper cuspids were also called eyeteeth, because in the past, it was thought that the eyes and these teeth shared the same nerve supply. Molars have between 3-5 cusps, but their name is taken from their function, not the number of pointed projections. Periodontal ligaments anchor the teeth in their sockets to the alveolar bone of the upper or lower jaw. Note that the reason that periodontal disease causes a loosening of the teeth is that the tooth/bone bond has been compromised or destroyed. The throat, or pharynx, is the passageway that connects the oral and nasal cavities with the esophagus (Fig. 5-5). It can be divided into three main parts: the nasopharynx, the oropharynx, and the hypopharynx. The nasopharynx is the most superior part of the pharynx, located behind the nasal cavity. The oropharynx is the part of the throat directly adjacent to the oral cavity, and the hypopharynx (also called the laryngopharynx because of its proximity to the larynx, which is the voice box) is the part of the throat directly below the oropharynx. The piriform recess (sinus or fossa) is the pear-shaped cavity in the hypopharynx near the opening to the voice box. This site is significant because food has a propensity for becoming lodged there. The peritoneal cavity is divided into two main regions: the greater sac and the lesser sac. These two regions are connected by an opening termed the epiploic foramen (also called the foramen of Winslow). The greater sac is the main cavity of the peritoneal cavity, while the lesser sac is formed by two separate folds termed omenta. The omenta (sing. omentum) are folds of peritoneum that extend from the stomach, further compartmentalizing the peritoneal cavity and serving as sites of fat deposition, protecting against trauma and infection, and providing an immune support function (Fig. 5-6). The greater omentum extends from the greater curvature of the stomach, covers the intestines, and merges into the parietal peritoneum. The lesser omentum (also termed the omental bursa) extends from the lesser curvature of the stomach and connects to the liver. The stomach, an expandable saclike vessel located between the esophagus and the small intestines, has three main functions (Fig. 5-7). It begins the process of digesting proteins by storing the swallowed food and mixing it with gastric juices and hydrochloric acid to further the digestive process chemically. This mixture is called chyme. The smooth muscles of the stomach contract to aid in the mechanical digestion of the food. A continuous coating of mucus protects the stomach and the rest of the digestive system from the acidic nature of the gastric juices. Finally, the partially digested mixture is moved to the small intestines. Once the chyme has been formed in the stomach, the pyloric sphincter relaxes a bit at a time to release portions of it into the first part of the small intestine, called the duodenum (Fig. 5-8). The small intestine gets its name, not because of its length (it is about 20 feet long), but because of the diameter of its lumen (a tubular cavity within the body). The second part of the small intestine is the jejunum and the distal part is the ileum. The duodenojejunal flexure is the border between the first two sections of the small intestines. In contrast to the small intestine, the large intestine (see Fig. 5-8) is only about 5 feet long, but it is much wider in diameter. The primary function of the large intestine is the elimination of waste products from the body. Some synthesis of vitamins occurs in the large intestine, but unlike the small intestine, the large intestine has no villi and is not well suited for absorption of nutrients. The ileocecal valve is the exit from the small intestine and the entrance to the colon. The first part of the large intestine, the cecum, has a wormlike appendage, called the vermiform appendix (pl. appendices), dangling from it. Although this organ does not seem to have any direct function related to the digestive system, it is thought to have a possible immunological defense mechanism. The accessory organs are the gallbladder (GB), liver, and pancreas (Fig. 5-9). These organs secrete fluid into the GI tract but are not a direct part of the tube itself. Sometimes accessory structures are referred to as adnexa. The liver forms a substance called bile, which emulsifies, or mechanically breaks down, fats into smaller particles so that they can be chemically digested. Bile is composed of bilirubin, the waste product formed by the normal breakdown of hemoglobin in red blood cells at the end of their life spans, and cholesterol, a fatty substance found only in animal tissues (Fig. 5-10). Bile is released from the liver through the right and left hepatic ducts, which join to form the hepatic duct. The cystic duct carries bile to and from the gallbladder. When the hepatic and cystic ducts merge, they form the common bile duct, which empties into the duodenum. Collectively, all of these ducts are termed bile vessels. Bile is stored in the gallbladder, a small sac found on the underside of the right lobe of the liver. When fatty food enters the duodenum, a hormone called cholecystokinin is secreted, causing a contraction of the gallbladder to move bile out into the cystic duct, then the common bile duct, and finally into the duodenum. The pancreas is a gland located in the upper left quadrant. It is involved in the digestion of the three types of food molecules: carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids. The pancreatic enzymes are carried through the pancreatic duct, which empties into the common bile duct. Pancreatic involvement in food digestion is an exocrine function because the secretion is into a duct. Pancreatic endocrine functions (secretion into blood and lymph vessels) are discussed in Chapter 15. Combining Forms for the Anatomy of the Digestive System

Digestive System

Recognize and use terms related to the anatomy and physiology of the digestive system.

Recognize and use terms related to the anatomy and physiology of the digestive system.

Recognize and use terms related to the pathology of the digestive system.

Recognize and use terms related to the pathology of the digestive system.

Recognize and use terms related to the procedures for the digestive system.

Recognize and use terms related to the procedures for the digestive system.

Functions of the Digestive System

Anatomy and Physiology

Overview

Oral Cavity

Throat

Peritoneum

Stomach

Small Intestine

Large Intestine

Accessory Organs (Adnexa)

Meaning

Combining Form

abdomen

abdomin/o, celi/o, lapar/o

accessory

adnex/o

anus

an/o

appendix

appendic/o, append/o

bile

chol/e, bil/i

bile vessel

cholangi/o

bolus

bol/o

cecum

cec/o

cheek

bucc/o

cholesterol

cholesterol/o

common bile duct

choledoch/o

corporis, body

corpor/o

duodenum

duoden/o

enamel

amel/o

esophagus

esophag/o

fat, lipid

lip/o, lipid/o

feces

fec/a

fold, plica

plic/o

fundus

fund/o

gallbladder

cholecyst/o

glucose, sugar

gluc/o, glyc/o

gums

gingiv/o

ileum

ile/o

intestines

intestin/o

jejunum

jejun/o

large intestine, colon

col/o, colon/o

lips

cheil/o, labi/o

liver

hepat/o

lobe

lob/o

lower jaw

mandibul/o

lumen

lumin/o

mouth, oral cavity

or/o, stom/o, stomat/o

mucus

mucos/o

nose

nas/o, rhin/o

nutrition

aliment/o

omentum

epiplo/o

palate

palat/o

pancreas

pancreat/o

peritoneum

peritone/o

pharynx, throat

pharyng/o

pylorus

pylor/o

rectum

rect/o

rectum and anus

proct/o

rugae

rug/o

saliva

sial/o, ptyal/o

salivary duct

sialodoch/o

salivary gland

sialoaden/o

sigmoid colon

sigmoid/o

small intestine

enter/o

starch

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access