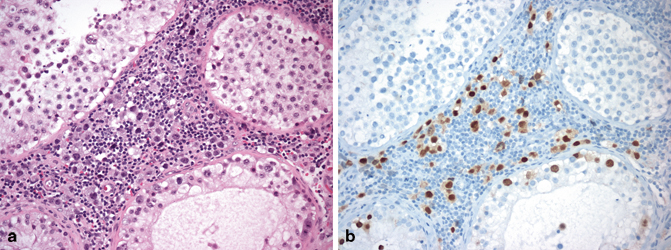

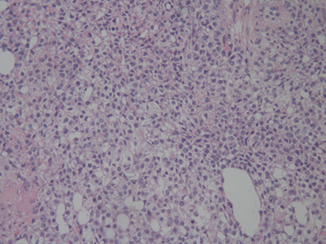

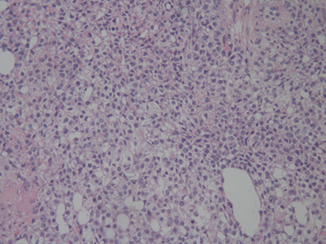

Fig. 37.1

Seminoma with marked lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate overwhelming the tumor cells

2.

Intertubular seminoma:

Seminoma cells usually form a solid sheet and displace the seminiferous tubules. However, the cells may also show an “intertubular” pattern of spread [3] where single cells infiltrate in an insidious pattern between the seminiferous tubules (Fig. 37.2a). Thus, the overall architecture of the testis is preserved and, at low power, no neoplasm may be apparent. This pattern is usually mixed with more solid appearing seminoma, but rarely in early stage disease; where there is plentiful intratubular germ cell neoplasia, unclassified type (IGCNU), intertubular foci may be missed. Clues to the presence of intertubular seminoma include an association with inflammation in the stroma and a rather more plentiful parenchyma between the seminiferous tubules. Immunostains for OCT4 may be helpful in identifying neoplastic cells (Fig. 37.2b) .

Fig. 37.2

Intertubular seminoma with single cells infiltrating between seminiferous tubules (a). OCT4 stains the neoplastic cells within the marked inflammatory infiltrate (b) and also intratubular germ cell neoplasia (IGCNU)

3.

Tubular and signet ring seminoma:

Morphological variants of seminoma cells themselves have been described relatively recently [2]. Occasionally a seminoma may mimic a nonseminoma, especially a glandular pattern yolk sac tumor (Fig. 37.3) or embryonal carcinoma, because of a tubular morphology . Cytology will usually differentiate between the two as the cells retain the classic cytomorphology of seminoma rather than the more variable nuclear morphology of yolk sac tumor or showing the more extreme nuclear overlapping, irregular contours and larger size of embryonal carcinoma . In ambiguous cases, immunochemistry for OCT4 (positive in seminoma, negative in yolk sac tumor), CD30 (negative in seminoma, positive in embryonal carcinoma) and CD117 or podoplanin (positive in seminoma, negative in embryonal carcinoma) is helpful. Signet ring morphology in seminoma has also been described. This may mimic a metastasis, but the foci of signet ring morphology have always been mixed with more typical areas, making this a less challenging diagnosis.

Fig. 37.3

A tubular seminoma showing classic seminoma nuclear morphology in spite of a pattern reminiscent of nonseminomatous germ cell tumor types

4.

Anaplastic seminoma:

Anaplastic seminoma is a term we do not recommend. Occasional seminomas have unusual features in terms of nuclear morphology , mitotic rate, or inflammatory infiltrate. The excellent prognosis of seminoma, however, means that a study involving many thousands of patients and standardized care would be necessary to identify, with certainty, such an entity and to prove its legitimacy by virtue of a more aggressive behavior than typical seminomas. Furthermore, it would be necessary to show that it could be reproducibly diagnosed, and neither of these requirements has been accomplished.

Spermatocytic Seminoma

Spermatocytic seminoma , as its pathogenesis and etiology are entirely separate from other germ cell tumors, should really be regarded as quite different from usual seminoma and needs to be considered apart. Unfortunately, it may be misdiagnosed as seminoma, and therefore inappropriate treatment could be instituted [4].

Patients with spermatocytic seminoma are older than most patients with testicular germ cell tumors, averaging 50–60 years of age. It is also more frequently bilateral than other germ cell tumors. Spermatocytic seminoma has never been described as originating in any site other than the testis and shows no special association with cryptorchidism; the presence of spermatogenesis is apparently necessary for its development, differentiating it from other germ cell tumors that may occur in extragonadal sites, particular those along the midline [5]. These features suggest that while other germ cell tumors arise from primordial germ cells (which may be misplaced), meiotic activity is necessary for the pathogenesis of spermatocytic seminomas. Molecular data also support the separate pathogenesis of these tumors [6] and implicate the primary spermatocyte as the cell of origin.

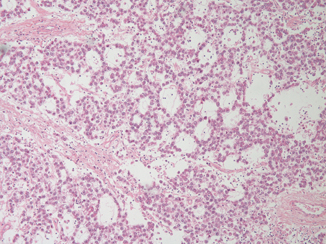

Spermatocytic seminomas typically show enormous cellular polymorphism. Three cellular populations occur: small lymphocyte-like degenerate cells, intermediate cells which have round nuclei with granular chromatin and variably prominent nucleoli, and giant cells which may be mononucleated or multinucleated, also with prominent nucleoli (Fig. 37.4). Some may also have a “spireme” chromatin pattern similar to that of meiotic phase spermatocytes. Mitoses, including atypical forms, and apoptosis are prominent. Intratubular growth of spermatocytic seminoma is common but there is no IGCNU.

Fig. 37.4

High power of a spermatocytic seminoma. One larger cell is seen, and there is more cellular size variation than usually seen in a classical seminoma

An “anaplastic” variant of spermatocytic seminoma has been described which consists mostly of intermediate cells [7]. However, this terminology appears inappropriate to us and, as the behavior of this variant is identical to the usual type of spermatocytic seminoma, we believe that there merely needs to be an awareness of the variability of the morphologic picture. Immunostains are negative for OCT4 but CD117 positivity is rather common. More recently, spermatocytic seminomas have been found to stain for the general germ cell tumor marker, SALL4 [8].

Despite its “malignant” appearance, spermatocytic seminoma metastasizes only exceedingly rarely. There are only two well-documented cases of metastasis. In the personal experience of one of the authors, who has also seen a case of spermatocytic seminoma metastasizing as a single lung nodule, this may be an “embolic” process. Adequate treatment, therefore, consists of orchiectomy alone without adjuvant treatment, since the potential mortality of further therapy exceeds the risk of tumor-related death.

Sarcomatous transformation is a rare complication of spermatocytic seminoma [9]. The sarcomatous component is often intermingled with usual type spermatocytic seminoma and can have an undifferentiated, spindle cell appearance or exhibit rhabdomyosarcomatous differentiation [10]. These tumors behave aggressively with about 50 % of the patients developing metastatic disease and dying of the tumor. The disseminated tumor consists only of the sarcomatous component.

Unusual Variants of Nonseminomatous Germ Cell Tumors

Solid Variant Yolk Sac Tumor

The varied patterns of yolk sac tumor can make the diagnosis challenging in rare cases. Some rare variants are seen mainly after treatment and will be discussed elsewhere; however, the solid variant of yolk sac tumor is seen in primary lesions and may be misdiagnosed .

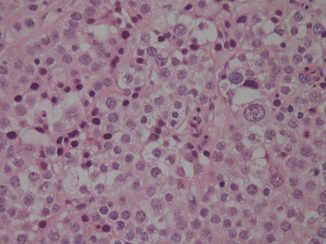

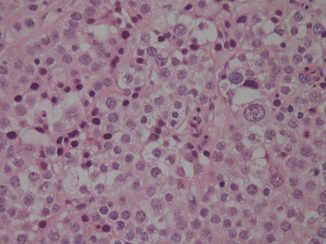

Solid variant yolk sac tumor is rare in its pure form, and is usually intermingled with other yolk sac tumor patterns and germ cell tumor elements such as embryonal carcinoma or teratoma. However, when pure, the solid variant shows more than a passing resemblance to seminoma (Fig. 37.5), thus leading to potential diagnostic confusion and the danger of mistreatment [11].

Fig. 37.5

Solid variant yolk sac tumor showing a mixture of large and also smaller cells, not seen in seminoma. Focal microcysts are also seen

Points of distinction include the lack in solid yolk sac tumor of the typical fibrous septa and lymphocytic infiltrate of seminoma, and the greater variation in nuclear size of most cases, with many examples showing cells with small nuclei and others with large nuclei, unlike seminoma where the nuclei are more uniformly large. Schiller–Duval bodies are not seen in the solid variant, but hyaline globules and bands of intercellular basement membrane can be very helpful as they do not occur in seminoma. The importance of knowing the serum markers is also emphasized: knowledge of a raised alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) should always lead one to suspect yolk sac tumor. Immunohistochemistry for AFP can be patchy in all yolk sac tumors and is even more apt to be negative in the solid pattern. For this reason glypican-3 is now a preferable immunochemical marker because of its greater sensitivity and consistent negativity in seminoma [12]. Another very helpful feature is negative reactivity for OCT4, contrasting with the seminoma. It is important to be aware that CD117 is frequently positive, potentially reinforcing confusion with the seminoma .

Teratoma

In the vast majority of postpubertal cases, teratoma is mixed with other elements, including embryonal carcinoma, trophoblast, seminoma, and yolk sac tumor. However, some cases of teratoma may cause diagnostic problems that may be difficult to resolve. Recent advances have also suggested some novel variants, which appear to have a separate pathogenesis and natural history .

Teratomas in postpubertal males, despite the lack of apparent malignant appearance in many cases, are capable of metastasis. In this they contrast significantly with the great majority of ovarian teratomas [13]. They may show immature elements, which are discussed below. They are almost inevitably associated with scarring of the surrounding testicular parenchyma with loss of normal spermatogenesis . Such scarring may be due to regression of other germ cell tumor components, thus explaining how, in spite of their indolent appearance, they are frequently accompanied by metastasis. The usual occurrence of IGCNU in the surrounding seminiferous tubules reinforces the close relationship of most postpubertal teratomas with the nonteratomatous germ cell tumors.

Immaturity in Teratomas

Immaturity is often seen in testicular germ cell tumors with a substantiatial amount of teratoma. Such foci typically form embryonic-type neuroectodermal elements, but other embryonic-type tissues (rhabdomyoblasts, nephrogenic blastema, and tubules) also qualify. As expected, such foci have a primitive appearance with active proliferation and apoptotic cells. It is also common for mature teratomatous elements to show atypical features, but these are not truly of embryonic type and therefore not considered “immature.” For instance, glandular-lined cysts may show stratification, atypical nuclei and mitoses; squamous epithelium may show dysplasia , and the stromal elements may show changes that in another situation would lead to a diagnosis of sarcoma [4]. Cartilage may show atypia, which in different contexts would lead to a presumption of chondrosarcoma. These atypical features reflect the derivation of postpubertal teratomas from other forms of germ cell tumors. Despite these changes, they do not affect the overall prognosis of the patient, and high threshold should be set for transformation to somatic-type malignancies in the primary testicular germ cell tumor, typically requiring overgrowth of a pure population of malignant-appearing mesenchymal or embryonic tissues to the exclusion of other elements and occupying at least a 4× low power microscopic field. For carcinomatous transformation an overtly invasive growth pattern is required. Because scattered embryonic-type elements do not confer a worse outcome, and given that pure “mature” postpubertal teratomas may be associated with metastases of either teratoma or nonteratomatous forms of germ cell tumor, the most recent WHO classification excluded immature teratoma as a diagnostic entity.

Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor

Some teratomas contain substantial overgrowth of primitive neuroectodermal tissue, and this should be separately recognized as primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET) . Most typically, PNET has morphology akin to PNETs of the central nervous system as most commonly seen in children. Many form primitive tubules resembling medulloepithelioma. In rare tumors, it eclipses all other elements, resulting in a pure PNET.

The prognostic implications of PNET limited to the testis are less worrisome than might be imagined. The small published series suggest that even in its pure form, most men are cured of their disease. However, they behave in a worse manner than teratomas without PNET [14]. This situation contrasts with finding PNET in metastases, which will be discussed separately.

When confronted with one of these cases, we suggest that the amount of PNET be accounted for in percentage form and mentioned specifically. Although, at present, standard germ cell tumor protocols generally apply, many oncologists recommend staging retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy for clinical stage I patients with a PNET component in their tumor rather than followup on a surveillance protocol.

Epidermoid Cyst

So called epidermoid cysts of the testis are composed of laminated keratin, usually in a well circumscribed nodule, most often 1–3 cm in diameter. Occasionally, the cyst may rupture leading to a less well circumscribed appearance.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree