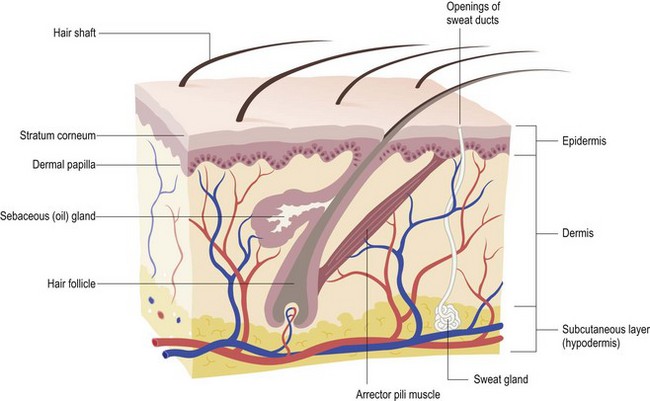

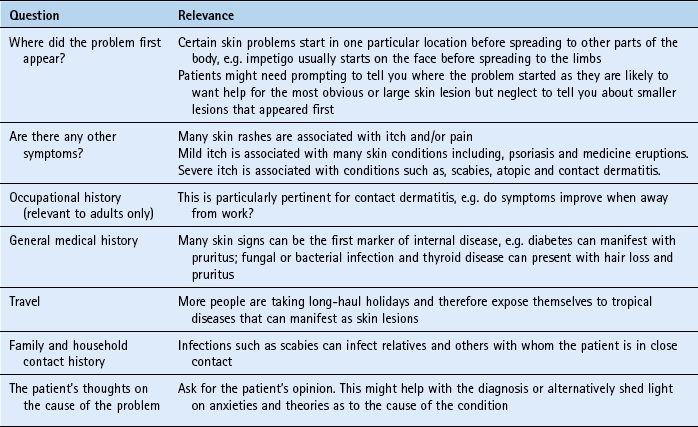

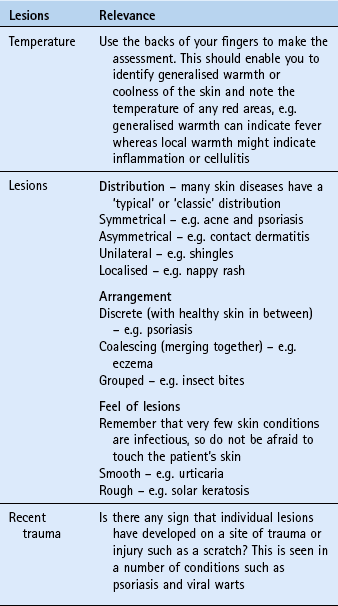

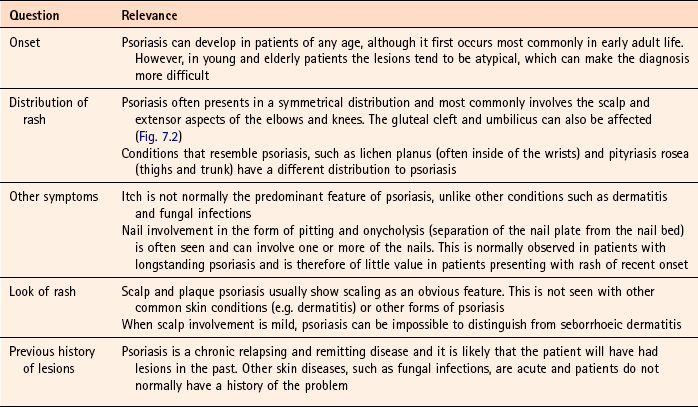

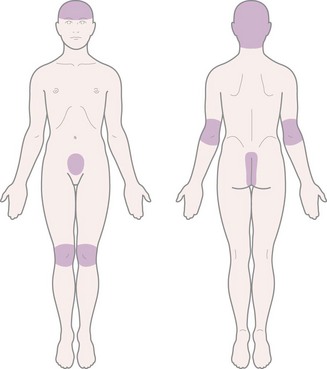

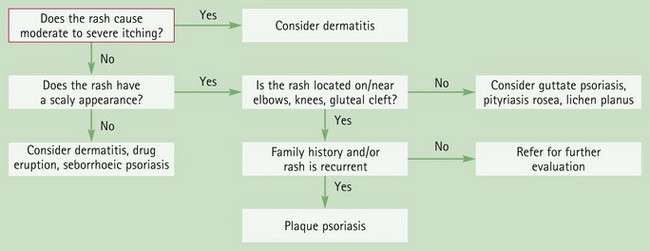

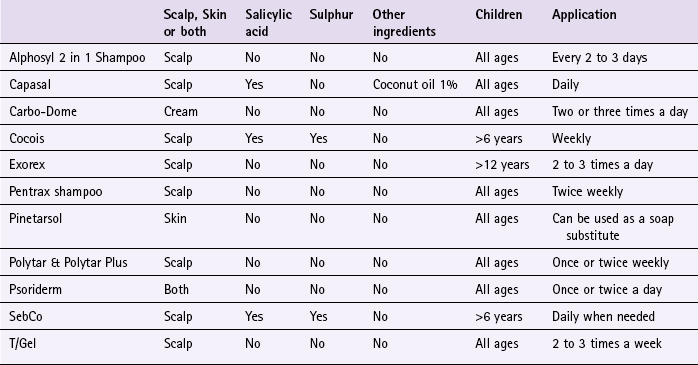

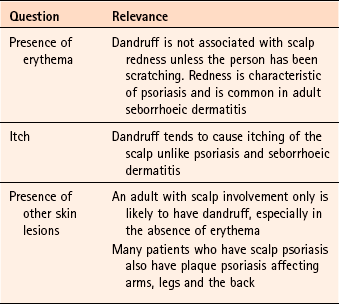

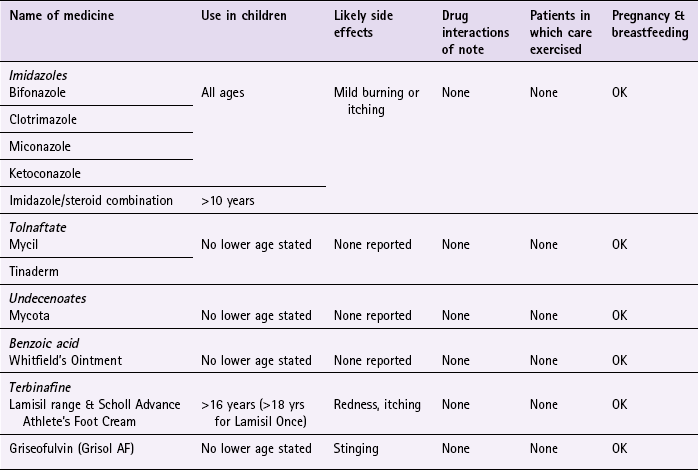

Chapter 7 Background Principally the skin consists of two parts, the outer and thinner layer called the epidermis and an inner, thicker layer named the dermis. Beneath the dermis lies a subcutaneous layer, known as the hypodermis (Fig. 7.1). Unlike internal medicine, the majority of dermatological complaints presenting in community pharmacy can be seen. This affords the community pharmacist an excellent opportunity to base his or her differential diagnosis not only on questioning but also on physical examination. General questions that should be considered when dealing with dermatological conditions are listed in Table 7.1. Terminology describing skin lesions can be confusing and the more common terms used are shown in Table 7.2. Table 7.2 Common terms used to describe skin lesions A more accurate differential diagnosis will be made if the pharmacist actually sees the person’s athlete’s foot or ‘rash’ on the back. Providing adequate privacy can be obtained there is no reason why the majority of skin complaints cannot be seen. If examinations are performed, clearly explain the procedure you want to perform and gain their consent. Examinations should be conducted in consultation rooms. It is worth remembering that many patients will be embarrassed by skin conditions and might be ashamed of their appearance. When performing an examination of the skin, a number of things should be looked for (Table 7.3). There is no substitute for experience when recognising skin problems. This is normally gained through seeing multiple cases; however, a free image bank (http://www.dermnet.com/) is available where familiarity can be gained of different presentations of skin conditions. Psoriasis can be located on various parts of the body (Fig. 7.2) and presents in a variety of different forms. Plaque and scalp psoriasis are the only forms of the condition that can be managed by the community pharmacist. It is therefore necessary that other forms of psoriasis, and conditions that look like psoriasis, can be recognised and distinguished. Asking symptom-specific questions will help the pharmacist to determine if referral is needed (Table 7.4). Plaque psoriasis classically presents with characteristic salmon-pink lesions with slivery-white scales and well defined boundaries (Fig. 7.3). Lesions can be single or multiple and vary in size from pinpoint to covering extensive areas. If the scales on the surface of the plaque are gently removed and the lesion is then rubbed, it reveals pinpoint bleeding from the superficial dilated capillaries. This is known as the Auspitz’ sign and is diagnostic. Scalp psoriasis can be mild, exhibiting slight redness of the scalp through to severe cases with marked inflammation and thick scaling (Fig. 7.4). The redness often extends beyond the hair margin and is commonly seen behind the ears. In this rare form of psoriasis sterile pustules are an obvious clinical feature. The pustules tend to be located on the advancing edge of the lesions and typically occur on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet (Fig. 7.5). Guttate psoriasis is characterised by crops of scattered small lesions (less than 1 cm) covered with light flaky scales that often affects the trunk and proximal part of the limbs (Fig. 7.6). This form of psoriasis usually occurs in adolescents and often follows a streptococcal throat infection and in people genetically predisposed to psoriasis. The condition is usually self-limiting. Tinea corporis can superficially look like plaque psoriasis. For further information on tinea infection see page 210. Mild scalp psoriasis can be very difficult to distinguish from seborrhoeic dermatitis. However, in practice this is rarely a problem since treatment for both conditions is often the same. For further information on seborrhoeic dermatitis see page 207. Goeckerman demonstrated the effectiveness of coal tar as early as 1925. This remained the mainstay of treatment until the introduction of dithranol, corticosteroids, and more recently, vitamin D and A analogues. A number of clinical studies have confirmed the beneficial effect coal tar has on psoriasis, although a major drawback in assessing the effectiveness of coal tar preparations is the variability in their composition making meaningful comparisons between studies difficult. Comparisons between coal tar and other treatment regimens have been conducted. Tham et al (1994) compared the effectiveness of calcipotriol 50 µg twice daily versus 15% coal tar solution each day. Both treatments were shown to be effective, although calcipotriol was significantly better than the coal tar solution. Harrington (1989) compared two pharmacy-only products, Psorin and Alphosyl. Findings showed that both helped in the treatment of psoriasis but Psorin (which includes 0.11% dithranol) was significantly more effective. Dithranol was first used in the 1950s and has become an established treatment option as clinical trials have established its efficacy. A systematic review in 2009 identified three placebo-controlled trials with dithranol, all demonstrating a statistically significant improvement over placebo (Mason et al 2009). There appears to be no definitive answer as to which strength is most appropriate, however, current practice dictates starting on the lowest possible concentration and gradually increasing the concentration until improvement is noticed. In addition, short contact regimens are advocated. However, one review of published studies involving short-contact dithranol therapy concluded that due to methodological flaws in many of the trials it is impossible to objectively determine the efficacy of this regimen (Naldi et al 1992). Prescribing information relating to the medicines used to treat psoriasis discussed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is summarised in Table 7.5; useful tips relating to patients presenting with psoriasis are given in Hints and Tips Box 7.1. All emollients should be regularly and liberally applied with no upper limit on how often they can be used. All are chemically inert and can therefore be safely used from birth onwards by all patients. They do not have any interactions with other medicines. For more information on emollients see page 242. All patient groups, including pregnant and breastfeeding women, can use the majority of products on either the skin or scalp. They have no drug interactions but can cause local skin or scalp irritation and stain skin and clothes. There has been recent concern over topical tar products association with an increased risk of skin cancer, although there is at present no firm epidemiological evidence (http://www.bad.org.uk/site/1114/default.aspx; accessed 13 November 2012). Harrington, CI. Low concentration dithranol and coal tar (Psorin) in psoriasis: a comparison with alcoholic coal tar extract and allantoin (Alphosyl). Br J Clin Pract. 1989;43:27–29. Mason, AR, Mason, J, Cork, M, et al. Topical treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009. [Issue 2. Art. No.: CD005028. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005028.pub2]. Naldi, L, Carrel, CF, Parazzini, F, et al. Development of anthralin short-contact therapy in psoriasis: survey of published clinical trials. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31:126–130. Tham, SN, Lun, KC, Cheong, WK. A comparative study of calcipotriol ointment and tar in chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:673–677. Clark, C. Psoriasis: first-line treatments. Pharm J. 2004;274:623–626. Dodd, WA. Tars. Their role in the treatment of psoriasis. Dermatol Clin. 1993;11:131–135. Freeman, K. Psoriasis: not just a skin disease. The Prescriber. 2007;5th June:42–45. 49 Gelfand, JM, Weinstein, R, Porter, SB, et al. Prevalence and treatment of psoriasis in the United Kingdom: a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1537–1541. Leary, MR, Rapp, SR, Herbst, KC, et al. Interpersonal concerns and psychological difficulties of psoriasis patients: effects of disease severity and fear of negative evaluation. Health Psychol. 1998;17:530–536. MacKie, RM. Clinical Dermatology. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press; 1999. Nevitt, GJ, Hutchinson, PE. Psoriasis in the community: prevalence, severity and patients’ beliefs and attitudes towards the disease. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135(4):533–537. Scon, P, Henning-Boehncke, W, Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1899–1912. Tristani-Firouzi, P, Kruegger, CG. Efficacy and safety of treatment modalities for psoriasis. Cutis. 1998;61:11–21. Dandruff (pityriasis capitis) Dandruff is very common and affects both sexes and all age groups, although it is unusual in pre-pubescent children. It has been estimated to affect 1–3% of the population (Gupta et al, 2004). Most patients will diagnose and treat dandruff without seeking medical help. However, for those patients that do ask for help and advice it is important to differentiate dandruff from other scalp conditions. Asking symptom-specific questions will help the pharmacist to determine if referral is needed (Table 7.6). Typically, seborrhoeic dermatitis will affect areas other than the scalp. In adults, the trunk is commonly involved, as are the eyebrows, eyelashes and external ear. If only scalp involvement is present then the patient might complain of severe and persistent dandruff and the skin of the scalp will be red. For further information on seborrhoeic dermatitis see page 207. The mechanism of action for crude coal tar in the management of dandruff is unclear, although it appears that tars affect DNA synthesis and have an antimitotic effect. There are virtually no published studies in the literature to assess the efficacy of coal tars in the treatment of dandruff. A review in Clinical Evidence identified one study comparing coal tar to placebo (Manrìquez & Uribe 2007). The study involving 111 people with seborrhoeic dermatitis or dandruff found coal tar reduced dandruff scores and redness compared to placebo at 29 days. Despite the lack of evidence, tar derivatives are found in a plethora of OTC medicated shampoos and have been granted FDA approval in America as an antidandruff agent. Prescribing information relating to the specific products used to treat dandruff and discussed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 7.7; useful tips relating to dandruff shampoo are given in Hints and Tips Box 7.2. Products containing coal tar are discussed under practical prescribing for psoriasis. For further information on coal tar products see page 203. Arrese, JE, Pierard-Franchimont, C, De-Doncker, P, et al. Effect of ketoconazole-medicated shampoos on squamometry and Malassezia ovalis load in pityriasis capitis. Cutis. 1996;58:235–237. Danby, FW, Maddin, WS, Margesson, LJ, et al. A randomized double-blind controlled trial of ketoconazole 2% shampoo versus selenium sulfide 2.5% shampoo in the treatment of moderate to severe dandruff. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:1008–1012. Nigam, PK, Tyagi, S, Saxena, AK, et al. Dermatitis from zinc pyrithione. Contact Dermatitis. 1988;19:219. Orentreich, N. Comparative study of two antidandruff preparations. J Pharm Sci. 1969;58:1279–1284. Pereira, F, Fernandes, C, Dias, M, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from zinc pyrithione. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;33:131. Peter, RU, Richarz-Barthauer, U. Successful treatment and prophylaxis of scalp seborrheic dermatitis and dandruff with 2% ketoconazole shampoo: Results of a multicentre, double blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:441–445. Pierard-Franchimont, C, Goffin, V, Decroix, J, et al. A multicenter randomized trial of ketoconazole 2% and zinc pyrithione 1% shampoos in severe dandruff and seborrhoeic dermatitis. Skin Pharmacol Appl Skin Physiol. 2002;15(6):434–441. Rigoni, C, Toffolo, P, Cantu, A, et al. 1% econazole hair shampoo in the treatment of pityriasis capitis; a comparative study versus zinc pyrithione shampoo. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 1989;124:67–70. Van Custem, J, Van Gerven, F, Fransen, J, et al. The in vitro antifungal activity of ketoconazole, zinc pyrithione and selenium sulfide against Pityrosporum and their efficacy as a shampoo in the treatment of experimental pityrosporosis in guinea pigs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:993–998. Seborrhoeic dermatitis Estimates of the prevalence of clinically significant seborrhoeic dermatitis range from 1 to 5% of the population, although cradle cap is reported to be more prevalent than the adult form (Naldi & Rebora 2009). Cradle cap usually starts in infancy, before the age of 6 months and is usually self-limiting; the adult form tends to be chronic and persistent. Seborrhoeic dermatitis is more common in adult men than women, and also more common in people with underlying neurological illness, for example, Parkinson’s disease (Johnson & Nunley 2000). Infantile seborrhoeic dermatitis is relatively easy to recognise but can sometimes be confused with atopic dermatitis. Arriving at a differential diagnosis of the adult form is more problematic as the condition can affect different areas and present with different degrees of severity. In mild cases it needs to be differentiated from dandruff and in more severe forms from allergic contact dermatitis, psoriasis and pityriasis versicolor. Asking symptom-specific questions will help the pharmacist to determine if referral is needed (Table 7.8). Cradle cap appears as large yellow, greasy scales and crusts on the scalp. This can become thick and cover the whole scalp (Fig. 7.10). Other areas can be involved such as the face and napkin area. Fig. 7.10 Infantile seborrhoeic dermatitis. Reproduced from R Kliegman, R E Behrman, W Emerson Nelson and H B Jenson, 2007, Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, Saunders Elsevier with permission. The adult form of seborrhoeic dermatitis is characterised by a history of intermittent skin problems. The distribution of rash is synonymous with skin areas with high numbers of sebaceous glands, typically the central part of the face, scalp, eyebrows, eyelids, ears, nasolabial folds and mid chest (Fig. 7.11). The rash is red with greasy looking scales and is mildly itchy. Blepharitis and otitis externa are also common secondary complications. In infants, atopic dermatitis usually presents as itchy lesions on the face and trunk. Scalp involvement is less common and the nappy area is usually spared. A positive family history of the atopic triad of dermatitis, asthma or hay fever is common. For further information on differentiating atopic dermatitis see page 291. Pityriasis versicolor, a yeast infection, can be mistaken for adult seborrhoeic dermatitis because the lesions exhibit fine superficial scale and are located on the upper trunk. The lesions are usually small (less than 1 cm) but can join together to form larger plaques. The condition is associated with warm climates and most people will have picked the infection up when on holiday. The rash does not itch significantly and the face is usually spared. It can be treated with antifungal lotions and shampoos (see Dandruff page 206), or if a small number of lesions with imidazole creams (see Fungal infections page 213). Antifungal shampoos such as ketoconazole, and selenium sulphide (2.5%) are applied for 10 minutes and then washed off, and this is repeated daily for 10 days. Imidazole creams are applied daily for 10 days. Bergbrant, IM, Faergemann, J. The role of Pityrosporum ovale in seborrheic dermatitis. Semin Dermatol. 1990;9:262–268. Danby, FW, Maddin, WS, Margesson, LJ, et al. A randomized double-blind controlled trial of ketoconazole 2% shampoo versus selenium sulfide 2.5% shampoo in the treatment of moderate to severe dandruff. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:1008–1012. Go, IH, Wientjens, DP, Koster, M. A double-blind trial of 1% ketoconazole shampoo versus placebo in the treatment of dandruff. Mycoses. 1992;35:103–105. Gupta, AK, Bluhm, R. Seborrhoeic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:13–26. McGrath, J, Murphy, GM. The control of seborrhoeic dermatitis and dandruff by antipityrosporal drugs. Drugs. 1991;41:178–184. Fungal skin infections Other tinea infections such as tinea corporis and tinea cruris might present in the community pharmacy but are uncommon Tinea unguium (nail infection) is covered separately on page 216. Tinea capitis is the commonest infection in children Worldwide but in Western nations is rare (for further information on fungal scalp infection see page 203). Dependent on the area affected the infection will manifest itself in a variety of clinical presentations (Fig. 7.12). Recognition of symptoms for each site affected will facilitate recognition and accurate diagnosis. All forms of tinea infection should be relatively easy to recognise, perhaps with the exception of isolated lesions on the body. Patients with athlete’s foot will often accurately self-diagnose the condition. However, the pharmacist should still confirm this self-diagnosis through a combination of questions (Table 7.10) and inspection of the feet. This is important as it also provides an opportunity to check for fungal nail involvement. Athlete’s foot is characterised by itching, flaking and fissuring of the skin and will appear white and ‘soggy’ due to maceration of the skin (Fig. 7.13). The feet often smell. The usual site of infection is in the toe webs, especially the fourth web space (web space next to the little toe). Fig. 7.13 Athlete’s foot. Reproduced from AB Fleischer et al 2000, 20 Common Problems, with permission of the McGraw-Hill Companies. Once acquired the infection can spread to other sites including the sole and instep of the foot. Over time this can infect the nails (see page 216 for fungal nail infection). Cases of tinea infection where the plantar surface has become involved may be persistent and difficult to treat. Tinea corporis is defined as an infection of the major skin surfaces that do not involve the face, hands, feet, groin or scalp. The usual clinical presentation is of itchy pink or red scaly slightly raised patches with a well-defined inflamed border (Fig. 7.14). Over time the lesions often show ‘central clearing’ as the central area is relatively resistant to colonisation. This appearance led to the term ringworm. Lesions can occur singly, be numerous or overlap to produce a single large lesion and appear polycyclic (several overlapping circular lesions). Terbinafine has been exempt from POM control in the UK since 2000. It inhibits the biosynthesis of ergosterol – an essential component of fungal cell membranes. Reviews have shown terbinafine to have high cure rates, slightly better than the imidazoles (Crawford & Hollis 2007). Imidazoles, like allylamines, act by inhibiting ergosterol production but at a later stage in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway. They have largely replaced benzoic acid, undecenoates and tolnaftate, because they have greater efficacy and an excellent safety record (Crawford & Hollis 2007). There appears to be no clinically significant differences in cure rates between the different imidazoles and treatment choice will probably be driven by patient acceptability and cost. Griseofulvin (as a 1% spray) works by inhibiting cellular mitosis. It has proven effectiveness when taken orally but has only limited trial data as a topical formulation. One trial reported an 80% mycological cure rate after 4 weeks with once daily application (Aly et al 1994). Prescribing information relating to specific products used to treat fungal infections and discussed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is summarised in Table 7.11 and products available summarised in Table 7.12; useful tips relating to patients presenting with fungal infections are given in Hints and Tips Box 7.3. Table 7.12 Summary of antifungal products and formulations Clotrimazole (e.g. Canesten range): Clotrimazole-containing products can be used for all dermatophyte and candida infections. Canesten and Canesten AF cream should be applied two or three times a day, where as Canesten Hydrocortisone can only be used twice a day. Bifonazole (Canesten Bifonazole Once Daily 1% w/w Cream): Bifonazole is licensed for athlete’s foot. For all patients the cream should be applied once daily. Ketoconazole (Daktarin Gold): Ketoconazole has a license for athlete’s foot, groin infection and candidal intertrigo. For athlete’s foot the cream should be applied twice a day for 1 week. For groin infections and candidal intertrigo, the cream should be applied once or twice daily. If no improvement in symptoms is experienced after 4 weeks treatment then the patient should be referred to the GP. For all conditions treatment should be continued for 2 to 3 days after all signs of infection have disappeared to prevent relapse. Miconazole (e.g. Daktarin range, Daktacort Hydrocortisone): Products containing miconazole only are suitable for patients of all ages and should be used twice a day. Treatment should continue for 10 days after all lesions have disappeared to prevent relapse. Daktacort hydrocortisone is suitable for children aged over 10 and is licensed for sweat rash and athlete’s foot. Aly, R, Bayles, CI, Oakes, RA, et al. Topical griseofulvin in the treatment of dermatophytoses. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:43–46. Crawford, F, Hollis, S. Topical treatments for fungal infections of the skin and nails of the foot. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007. [Issue 3. Art. No.: CD001434. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001434.pub2]. Drake, LA, Dinehart, SM, Farmer, ER, et al. Guidelines of care for superficial mycotic infections of the skin: tinea corporis, tinea cruris, tinea faciei, tinea manuum, and tinea pedis. Guidelines/Outcomes Committee. American Academy of Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:282–286. Elewski, B. Tinea capitis. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:23–31. Moriarty, B, Hay, R, Morris-Jones, R. The diagnosis and management of tinea. BMJ. 2012;345:e4380. Fungal nail infection (onychomycosis) It is estimated that over 10% of the general population suffer from onychomycosis (Thomas et al 2010). The incidence of infection increases with increasing age and is particularly common in people aged over 70 years of age (e.g. estimated at up to 50%).

Dermatology

General overview of skin anatomy

History taking

Term

Description

Macule

A flat lesion which is less than 1 cm in diameter

Patch

A flat lesion which is greater than 1 cm in diameter

Papule

A raised solid lesion less than 1 cm in diameter

Nodule

A raised solid lesion greater than 1 cm in diameter

Vesicle

A clear fluid filled lesion lasting a few days which is less than 1 cm in diameter

Bulla

A clear fluid filled lesion lasting a few days which is greater than 1 cm in diameter

Pustule

A pus filled lesion lasting a few days which is less than 1 cm in diameter

Comedone

A papule which is ‘plugged’ with keratin and sebum

Erythema

Redness due to dilated blood vessels that blanch when pressed

Excoriation

Localised damage to the skin due to scratching

Lichenification

Thickening of the epidermis with increased skin markings due to scratching

Physical examination

Psoriasis

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

Clinical features of plaque psoriasis

Clinical features of scalp psoriasis

Conditions to eliminate for plaque psoriasis

Guttate psoriasis (also known as raindrop psoriasis)

Tinea corporis

Conditions to eliminate for scalp psoriasis

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Coal tar

Dithranol

Practical prescribing and product selection

Emollients

Tar-based products

References

Prevalence and epidemiology

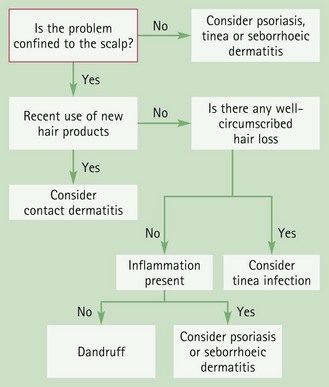

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

Conditions to eliminate

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Coal tar

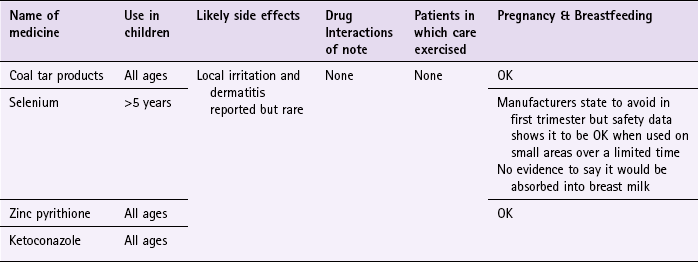

Practical prescribing and product selection

Coal tar products

Prevalence and epidemiology

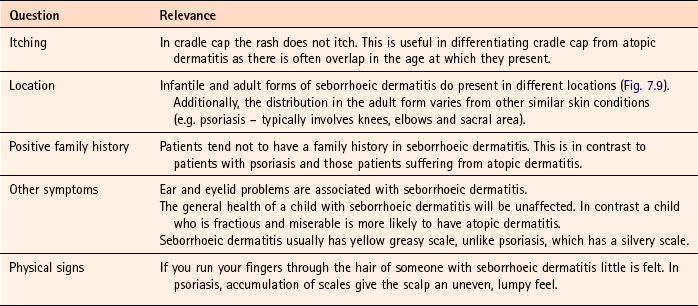

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

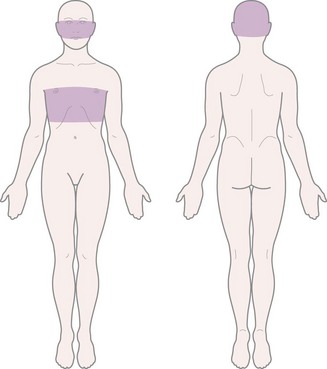

Clinical features of seborrhoeic dermatitis

Conditions to eliminate

Pityriasis versicolor (meaning bran-like scaly rash of various colour)

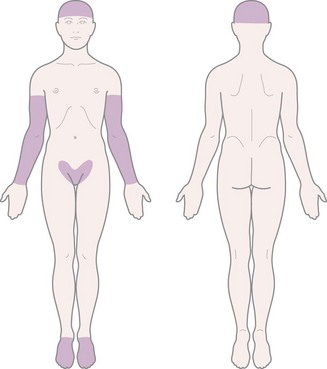

Prevalence and epidemiology

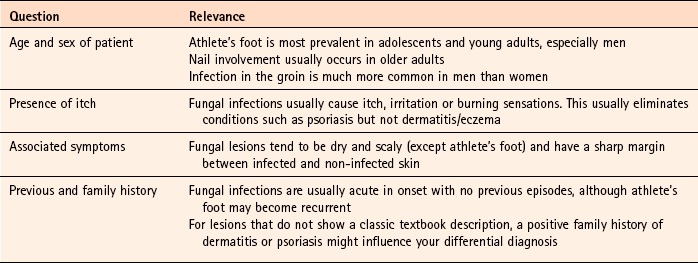

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

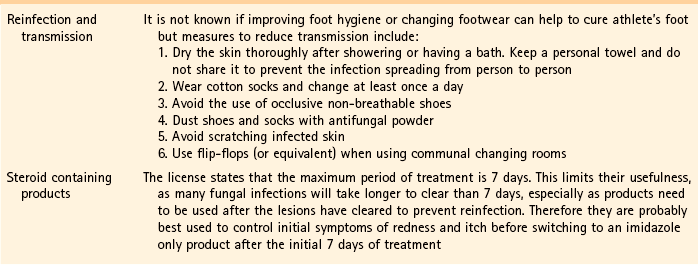

Clinical features of tinea infections

Tinea corporis

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Allylamines

Imidazoles

Griseofulvin

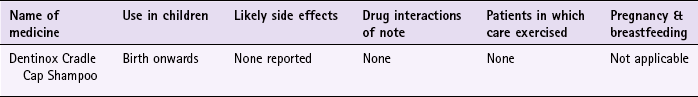

Practical prescribing and product selection

Active ingredient

Brand

Formulations

Bifonazole

Canesten Bifonazole Once Daily

Cream

Clotrimazole 1%

Canesten AF

Cream, spray

Canesten

Cream, spray, solution

Clotrimazole 1% & Hydrocortisone 1%

Canesten Hydrocortisone

Cream

Miconazole 2%

Daktarin Activ

Cream, spray, powder

Daktarin

Cream and powder

Miconazole 2% & hydrocortisone 1%

Daktacort Hydrocortisone

Cream

Ketoconazole

Daktarin Gold

Cream

Terbinafine

Lamisil AT

Spray, cream, gel

Lamisil Once

Solution

Scholl Advance Athlete’s Foot Cream

Cream

Tolnaftate

Mycil

Ointment, spray, powder

Scholl Athlete’s foot

Cream, spray, powder

Tinaderm

Cream

Undecenoic acid

Mycota

Cream, spray, powder

Imidazoles

References

Prevalence and epidemiology

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Dermatology