37

CHAPTER OUTLINE

■ DEFINITIONS RELATED TO SUBSTANCE USE AND ABUSE

■ CULTURE AND PATTERNS OF SUBSTANCE USE AND ABUSE

■ CULTURAL ASPECTS OF CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

■ ADDICTION AND PATIENTS’ CULTURAL FUNCTION

■ CULTURE, TREATMENT, AND RECOVERY

Addictive disorders can vary widely across nations and cultures. For example, high rates of alcohol abuse and dependence occur in several countries of Eastern Europe, especially Hungary, Poland, and Rumania (1), the aboriginal people of Australia (2), and the Northern Plains Indian tribes of North America (3). Likewise, ethnic groups in Southeast Asia that raise poppy as a cash crop (e.g., Hmong, Iu Mien) have high rates of opium dependence (4). Social disruption and armed conflict can lead to widespread addiction (5). At times, sociocultural subgroups can manifest high rates. For example, 40% to 50% of college students in the United States report an episode of binge drinking (5 drinks or more for men, 4 drinks or more for women) in the last 2 weeks (6), with Euroamerican men and women having the highest rates of heavy drinking and alcohol-related problems (7). Some nations have demonstrated the ability to notably reduce the prevalence of addiction, such as the decline of opium use in China during the latter half of the 20th century (8).

As a means of enhancing their effectiveness, clinicians need to appreciate the interactions between culture and addiction. Basic to assessing cultural factors is the ability to take a culture–ethnicity history (9).

DEFINITIONS RELATED TO SUBSTANCE USE AND ABUSE

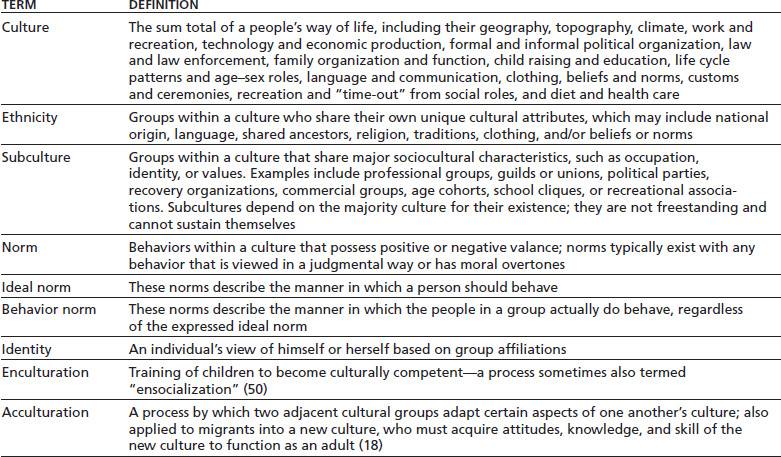

Several concepts are helpful in guiding the addiction specialist in understanding the role of culture in contributing to, as well as alleviating, addictive disorders (see Table 37-1 for a list of these terms). Cultures typically have laws or traditions regarding substance production, distribution, and consumption. Most nations encompass numerous ethnic groups. Within a culture, ethnic groups can differ greatly in their use of alcohol and other psychoactive substances. Their attitudes, values, or practices may resemble or differ from those of the culture at large (10).

TABLE 37-1 DEFINITION OF CULTURE-RELATED TERMS WITH UTILITY IN UNDERSTANDING, ASSESSING, AND TREATING SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

Groups of people with substance use disorder can comprise subcultures, such as a drug or drinking subculture tied to a particular using context (e.g., neighborhood tavern, crack house, or college party house) (11). Any one person may belong to more than one subculture or ethnic group, which can enrich the human experience as well as create norm conflicts. From your patient’s standpoint, affiliation with a recovery-oriented subcultures that shares norms and values can reduce stress (and relapse risk) during recovery.

An ideal norm might prescribe use of a substance under certain circumstances, such as drinking wine during Jewish Passover or consuming peyote in the Native American Church. Or, an ideal norm may demand abstinence, such as abstention from alcohol by many Moslem sects or abstention from tobacco by Seventh Day Adventists. Behavioral norms consist of what people actually do (12). A norm gap or conflict occurs if the ideal norm and behavioral norm conflict. In cultures with norm conflicts regarding substance use, substance disorders predictably ensue (13). Bringing norm conflicts to the patient’s awareness can be useful in the journey to a culturally syntonic recovery.

Exploring the individual’s identity can lead to valuable insights that can guide interventions as part of motivational interviewing. For example, asked about his identity, one patient replied, “I’m what you might call a common drunk, doc, but I’m not an alcoholic.” This response led to a useful conversation regarding the patient’s criteria for these categories and why he was willing, even anxious, to accept one identity while vehemently rejecting the other. Entrenched negative identities (e.g., “common drunk,” “pot head”) can serve as a justification for continued addiction and avoidance of recovery (14).

CULTURE AND PATTERNS OF SUBSTANCE USE AND ABUSE

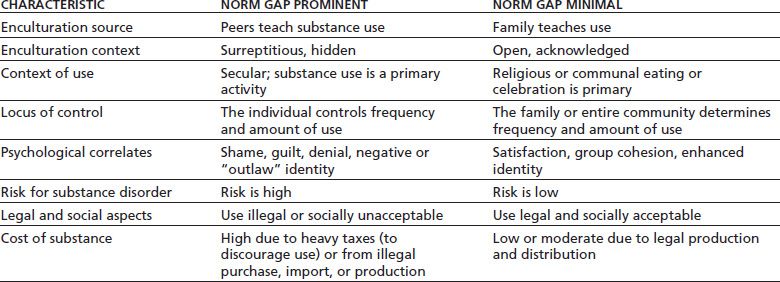

Among groups in which ideal norms and behavioral norms regarding substance use are identical, substance abuse rarely exists. On the other hand, groups that prohibit use of a substance in theory and yet allow it in practice invite individuals to decide use on their own. This circumstance results in some people using the substance excessively. Current examples of norm conflicts fostering increased substance abuse in the United States include legalized medical marijuana in certain states (15), opioid prescribing for “chronic pain,” (16) and college binge drinking (6). Table 37-2 shows the concomitants of substance use in association with norm conflicts (17).

TABLE 37-2 CONSEQUENCES OF SUBSTANCE USE DEPENDING ON PRESENCE VERSUS ABSENCE OF NORM CONFLICT

Appreciating ethnic patterns of substance use and abuse in the United States can provide a useful primer for the beginner (18), but relying on general trends can be misleading for the following reasons:

■ Within any large population, considerable differences exist among subgroups. For example, Korean Americans tend to have higher rates of substance disorder than other Asian American groups (19).

■ Rates of substance disorder may change with the generations since immigration. For example, Mexican American women have extremely low rates of substance disorder in the first generation after immigration, but rates comparable to other American women in the second and subsequent generations (20).

■ Sociocultural changes within ethnic groups can affect the pattern of substance use and disorder over time. For example, many Hispanic Americans have abandoned Roman Catholicism for abstinence-oriented Protestantism in an effort to resolve alcohol disorder (21). An Asian American immigrant group, the Hmong, formerly had no norm gap with regard to alcohol use and virtually no alcohol disorder. However, widespread conversation to abstinence-oriented Protestantism resulted in a norm conflict regarding drinking and the appearance of alcohol disorder (22).

Clinicians must conduct individual assessments for each new patient while avoiding stereotyping. Failure to do so results in both missed diagnosis (in patients from groups with low rates of substance disorder) and erroneous overdiagnosis (in patients from groups with high rates of substance disorder).

CULTURAL ASPECTS OF CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

Taking a Cultural History

The first step in conducting a cultural history consists of asking the patient about the ethnic origins of his or her parents and grandparents. Their place of birth, national origin, language learned at home, migrations, roles and affiliations in the ethnic community and in the community-at-large, educational experiences, or marital history may be relevant, depending on the case. The second step consists of assessing the family’s overall enculturation of the patient into his or her ethnic groups of origin (23). Was one or more of the parenting adults actively abusing substances during the patient’s childhood? Parental substance disorder can disrupt a health identity formation and undermine cultural competence (24). Inability to work, to play, and to have meaningful relationships increases the risk to addiction (25).

Adapting to life in an unfamiliar culture can involve stressors that may precipitate excessive substance use (26). Adoption or foster home placement can also affect ethnic affiliation and identity, especially if the new parents differ in their ethnic origins from the biologic parents (27). The developing child’s enculturation, which may involve integrating distinctly different cultural norms and values, can affect the use of psychoactive substances. During late adolescence or early adulthood, the patient may have chosen to relocate away from the family/community of origin and into a more mainstream community, such as college, the military, or a cross-ethnic marriage (28).

Cultural groups ensocialize young people in psychoactive substance using specific methods. Inquiry into these methods can help both the patient and the clinician in understanding the patient’s earlier decisions regarding substance use, as follows:

■ Observations of role models: What substances did the parenting adults use in the home or outside of the home? Was the use excessive, associated with problems, or disruptive to the family?

■ Socialization into psychoactive substance use: Who first taught or guided the patient’s use of psychoactive substances? Did this occur in the home and family or outside with peer groups? Who were these mentors and what substances or instruction did they provide? How old was the patient at the time?

■ Early experience with substance use: Who determined the substances, occasions for use, dose, and patterns of use? Was it the patient, family, or peers? Were these teachers substance abusers themselves? How did early use assist coping in the family, in school, at work, or while dating?

■ Linkage with other developmental tasks: Was the patient learning other developmental tasks at the same time? These other developmental tasks might include recreation, courting, acquisition of social skills, early sexual experiences, or coping with illness or anxiety.

ADDICTION AND PATIENTS’ CULTURAL FUNCTION

The relationship between psychoactive substances and social performance is a complex one. Psychoactive substance use may foster social coping, at least initially. For example, use of stimulants may contribute to studying, athletics, working, or coping with lack of sleep. Over time, if addiction ensues, it generally undermines performance.

Young people may use psychoactive substances as aids in acquiring social competence. An example in the 19th century was the use of the herbal anticholinergic drug belladonna or “beautiful lady” to produce rosy cheeks and project an image of health and vigor. Alcohol, cannabis, opiate, sedative, or tobacco use can relieve social anxiety or alleviate performance anxiety. Symptom-relieving use may escalate if anxiety persists, as in the following case:

CASE EXAMPLE

A college freshman found that one drink before attending a party alleviated her severe anxiety about socializing with new people. By her 3rd year, she required several drinks to achieve the same effect as formerly achieved with one or two drinks. Consequently, she was showing up intoxicated at social events. This led to an intervention by her peers, who had become alarmed at her drunken behavior. She sought professional opinion, complied with treatment recommendations, and was successfully treated for social phobia. Abstinence was recommended in view of her propensity to anxiety disorders, her family history of substance disorder, and her own escalation to heavy drinking. She joined an abstinence-oriented recovery group composed of college students.

Loss of social coping during the course of substance use disorder is a common feature of addiction in all cultures (17). Indeed, the achievement of a certain social stature in a community followed by gradual loss of status is a common presenting feature in addictive disorders. Examples of status loss include the following:

■ Marital status: divorce, repeated failed marriages, and liaisons of ever-shorter duration

■ Employment status: jobs of brief duration at a status below one’s level of training or education, longer periods of unemployment, inability to obtain a job, and losing jobs because of positive alcohol or drug screening tests

■ Housing: living with friends who abuse substances, living in institutional settings (e.g., halfway houses, shelters), and homelessness

■ Community participation: alienation and isolation from non–substance-related groups, events, and activities

■ Friends: most friends use substances heavily

■ Legal: breaking laws related to driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs, drug possession or sale, property law offenses, and assault

■ Financial: inability to pay bills, selling property to buy alcohol or drugs, and bankruptcy

The addiction subculture may comprise a welcome identity group to a person estranged from family and other groups. Drinking and drug subcultures do not impose hurdles of the kind that distinguish career advancement, achievement on the sports field, or time or effort invested in family and community activities. The norms and values of the drug subgroup are congenial to the addicted person, unlike norms and values of community organizations. Thus, young people who have failed social advancement may drift toward the identity proffered by a drug subculture.

CULTURE, TREATMENT, AND RECOVERY

Addiction and the Normal Social Plexus

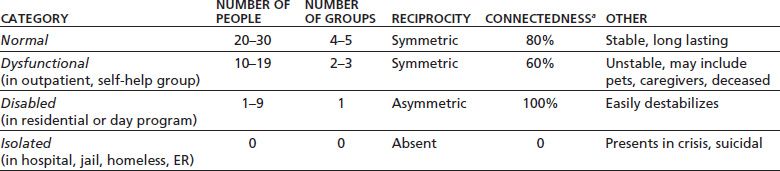

The normal social plexus consists of 20 to 30 people organized into four or five groups (29) (Table 37-3). Typical plexus groups include the face-to-face living group, relatives, friends, coworkers, and perhaps another group or two (e.g., neighbors, association members, church or recreational group members). The chance that any one person knows another in the proband’s (the identified individual) social plexus (the plexus “connectedness”) is about 80%. The group tends to be stable: Even if a proband and another member become alienated for a time, the group overrides antipathy and foster rapprochement. In this way, the social plexus promotes the settling of inevitable interpersonal problems, thereby enhancing maturation and interpersonal intimacy over time. Plexus associations are reciprocal: that is, the proband exchanges work, time, or resources with other members of his/her plexus—a major factor in the limitation of the plexus to around 20 to 30 people (and rarely into the 40s or more). Favazza observed that middle-class, middle-aged, married, employed alcohol-dependent patients coming to treatment had “normal” social plexus by the numerical criteria enumerated here (30). However, they lost about half of their social plexus members (mostly other heavy drinkers) during early recovery.

TABLE 37-3 CHARACTERISTICS OF THE INTIMATE SOCIAL PLEXUS IN RELATION TO CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS

aLikelihood that any one person in the plexus knows anyone else in the plexus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree