58

CHAPTER OUTLINE

Contingency management (CM) interventions and community reinforcement approach (CRA) therapy for treating substance use disorders (SUDs) are based in the conceptual framework of learning and conditioning theory. Especially fundamental to these treatment approaches is operant conditioning, which is the study of how systematically applied environmental consequences increase (i.e., reinforce) or decrease (i.e., punish) the frequency and patterning of voluntary behavior (1). The approaches are also informed by the disciplines of behavioral pharmacology regarding the fundamental role of the reinforcing effects of abused substances in promoting SUDs and behavioral economics regarding the potential role of systematic biases in how humans make choices in complex environments and how they may increase the likelihood of SUDs and other health problems (2).

In this chapter, we describe how SUDs are conceptualized within such a theoretical framework, describe the treatments, and review controlled studies on the efficacy of CM and CRA in the treatment of SUDs. These interventions have been researched most extensively with regard to treating alcohol, cocaine, and opioid dependence, each of which is addressed in this chapter. More recently, CM and CRA have been extended to other forms of SUDs and to special populations (2,3). Those advances are reviewed as well. The review is restricted to controlled studies published in peer-reviewed journals. The only exceptions are where an uncontrolled study is mentioned as the first in a series of studies that included a controlled trial.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

Studying and conceptualizing SUDs within an operant conditioning framework began in earnest in the 1960s and early 1970s (4). Convergent evidence from studies conducted with laboratory animals residing in highly controlled experimental chambers, humans with SUDs residing in medically supervised hospital settings, and humans seeking treatment for SUDs demonstrated the operant nature of drug use. In the studies with laboratory animals, for example, subjects fitted with intravenous catheters readily learned arbitrary behavioral responses such as pressing a lever or pulling a chain when the only consequence for doing so was the delivery of an injection of a commonly abused drug (e.g., morphine or cocaine). Effects were pharmacologically specific in those injections of drugs that humans rarely abuse (e.g., chlorpromazine) or saline failed to generate or maintain responding. In some instances, the reinforcing effects of the commonly abused drugs were so robust that they promoted in these laboratory animals the dangerous extremes in consumption characteristic of humans with SUDs. Monkeys given unconstrained opportunities to self-administer intravenous cocaine, for example, would consume the drug to the exclusion of basic sustenance, and barring experimenter intervention, to the point of death (5). Substitute saline for the cocaine, and the animals would readily discontinue giving themselves injections (i.e., responding extinguished). A robust body of evidence demonstrated that the drugs that humans commonly abuse function as unconditioned positive reinforcers much as do food, water, and sex (4).

The residential studies of humans with SUDs often examined the sensitivity of drug use to systematically administered environmental consequences. An elegant series of studies, for example, demonstrated the operant nature of alcohol use among severe alcoholics (6). In this programmatic series of studies, alcoholics resided on an inpatient unit where they were permitted to purchase and consume alcoholic drinks. Abstinence from voluntary drinking increased when (a) access to an alternative reinforcer (enriched environment) was made available contingent on doing so, (b) monetary reinforcement was provided contingent on abstinence from drinking, (c) the amount of work required to obtain drinks was increased, or (d) brief periods of social isolation were imposed contingent upon drinking. The studies provided strong evidence that even among individuals with diagnosed severe SUDs, drug use was sensitive to environmental consequences.

Initial studies with treatment seekers typically involved small-sample demonstrations that systematically applied consequences could improve treatment outcome. In a controlled case study, for example, breath samples were collected twice weekly on a quasi-random schedule from a male with severe alcoholism (7). Baseline observations demonstrated a high rate of drinking. During the intervention period, the patient received a $3.00 coupon book contingent on randomly scheduled alcohol-negative breath samples. Coupons could be exchanged for goods at a hospital commissary. After a discernible increase in the rate of negative breath tests during the period of contingent coupon delivery, the contingency was removed, and booklets were delivered independent of breath results. Under that condition, the frequency of negative specimens decreased toward baseline levels. Reimposing the contingency again increased the frequency of alcohol-negative breath results. Around this same time, several studies were reported suggesting that allowing participants to earn back monetary deposits contingent on objective verification of smoking abstinence improved outcomes among those trying to quit cigarette smoking (8,9). These studies illustrated the clinical implications of the emerging body of evidence supporting the operant nature of SUDs.

Such studies provided the empirical foundation for a conceptual model wherein drug use is considered a normal, learned behavior that falls along a continuum ranging from little use and few problems to excessive use and many untoward effects (4,10). The same principles of learning and conditioning are assumed to operate across this continuum. Within this framework, all physically intact humans are considered to possess the necessary neurobiologic systems to experience drug-produced reinforcement and hence to develop drug use and SUDs. Genetic or acquired characteristics (e.g., family history of alcoholism, other psychiatric disorders) are recognized as factors that affect the probability of developing SUDs but are not deemed to be necessary for the problem to emerge.

TREATMENT MODEL

Within an operant conceptual framework, reinforcement derived from drug use and the associated lifestyle is deemed to have monopolized the behavioral repertoire of the user. Treatments developed within this framework are designed to reorganize the user’s environment to systematically increase the rate of reinforcement obtained while abstinent from drug use and reduce or eliminate the rate of reinforcement obtained through drug use and associated activities. Primary emphasis is placed on decreasing drug use by systematically increasing the availability and frequency of alternative reinforcing activities through either relatively contrived sources of reinforcement as in CM interventions or more naturalistic sources as in CRA therapy (2,11). Additionally, arranging the environment so that aversive events or the loss of reinforcing events (i.e., punishment procedures) occurs as a consequence of drug use also can decrease drug use. As with reinforcement, such aversive procedures can involve relatively contrived (e.g., forfeiture of a large-value incentive) or more naturalistic (e.g., suspension from work) consequences. This distinction between CM and CRA with regard to the former’s relying primarily on contrived contingencies and the latter’s relying primarily on naturalistic contingencies will become clearer when the treatments are described in greater detail later. By contrived, we mean a set of contingencies that are put in place explicitly and exclusively for therapeutic purposes (e.g., earning vouchers exchangeable for retail items contingent on cocaine-negative urine toxicology results). By naturalistic, we mean a set of contingencies that are already operating in the natural environment for nontherapeutic purposes but can be used to support the therapeutic process (e.g., teaching a spouse to deliver praise when a patient avoids bars and to withhold praise or express disapproval for going to bars).

Some treatments, such as the CRA + voucher treatment for cocaine dependence (12,13), are designed to deliver contrived consequences during the initial treatment period, with a transition to more naturalistic sources later in treatment. The rationale for that sequence is that the lifestyle of the user is often so disrupted upon treatment entry that it is largely devoid of effective alternative sources of reinforcement that can compete with the reinforcement derived from drug use. Contrived sources of alternative reinforcement delivered through CM are designed to promote initial abstinence, thereby allowing time for therapists and patient to work toward reestablishing more naturalistic alternatives (e.g., job, stable family life, participation in self-help and other social groups that reinforce abstinence). Of course, it is these naturalistic alternatives that eventually will need to sustain long-term abstinence once the contrived reinforcers are discontinued.

Also important to recognize is that for any number of reasons, some patients may have behavioral repertoires that are too limited to recruit sufficient sources of naturalistic reinforcement to effectively compete with drug use, and, as such, these patients will need some form of maintenance treatment involving contrived reinforcement contingencies in order to sustain long-term abstinence. Certainly that is widely recognized with opioid-dependent individuals who often need a maintenance pharmacotherapy in order to sustain long-term abstinence from illicit drug use. Others may need lifelong participation in self-help programs in order to succeed. Such programs might be deemed as falling somewhere around the midpoint on the continuum of contrived versus naturalistic sources of alternative reinforcement

(11). The following discussion illustrates how this general strategy is implemented in CM and CRA interventions.

TREATMENT PLANNING

A thorough patient evaluation is an essential first step in effective clinical management of SUDs and that certainly holds true when using CM and CRA interventions. In this section, we outline the assessment practices used in the CRA + voucher treatment for cocaine dependence to illustrate the type of assessments conducted when using CM and CRA interventions (13). The assessment framework is relatively generic and can be readily applied to other types of SUDs by substituting information specific to cocaine use with pertinent information on whatever other type of SUD is the presenting problem.

Every effort is made to schedule an intake assessment interview as soon as possible after initial patient contact with the clinic. Scheduling the interview within 24 hours of clinic contact significantly reduces attrition between the initial clinic contact and assessment interview, which is a substantial problem among those with SUDs (14). Some patients cannot come in to the clinic within 24 hours, so secondary plans are made to get them in within 72 hours or as soon as is practicable.

Detailed information is collected on drug use, treatment readiness, psychiatric functioning, employment/vocational status, recreational interests, current social supports, family and social problems, and legal issues. The following is a list of instruments that we use to obtain such information, listed in the order in which they are typically administered. Modifications can be readily made to the list depending on the population being treated. We use several patient-rated questionnaires that can be completed upon clinic arrival for an intake assessment. We have clients complete a brief demographics questionnaire. Obtaining a current address and phone number is important, as is a number of someone who will always know the client’s whereabouts. This information is important for purposes of during-treatment outreach efforts should the client stop coming to scheduled therapy sessions or need to be contacted for other clinical purposes and for contacting clients for routine posttreatment follow-up evaluations. The Stages of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale (SOCRATES) (15) provide information on the clients’ perception of the severity of their drug use problems and their readiness to engage in behavior to reduce their use. We use three versions of the SOCRATES that refer to specific substances (i.e., cocaine, alcohol, and other drug use), as the patient’s motivation to reduce substance use is often drug specific.

We use an adaptation of the Cocaine Dependency Self-Test (16) to collect information on the type of adverse effects from cocaine use that patients have experienced. Such information can be useful in helping patients problem solve regarding the pros and cons of cocaine use as part of efforts to promote and sustain motivation for change during the course of treatment. A sizeable proportion of patients with illicit drug use disorders are also problem drinkers, making assessment of that problem essential. As part of our alcohol assessment, we use the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test, a widely used brief alcoholism screening instrument (17), along with a drug history questionnaire described later. Depressed mood is another common problem among those presenting for treatment for drug use disorders. We use the Beck Depression Inventory to screen for depressive symptoms (18). The SCL-90-R (19) is also used to screen for psychiatric symptoms more broadly and is helpful in determining whether a more in-depth psychiatric evaluation is warranted.

A semistructured drug history interview developed in our clinic is used to facilitate the collection of information on current and past substance use. Such detailed information is essential for proper treatment planning. The goal in completing a drug use history is to obtain detailed information regarding the duration, severity, and pattern of the patient’s drug use. The accuracy of the patient’s report of drug use (amount and frequency) is facilitated by the use of an effective technique for reviewing recent use (i.e., the timeline follow-back) (20). Diagnoses of abuse and dependence are made later by master’s- or doctorate-level psychologists. We use the addiction severity index (ASI) (21) to assess multiple problems commonly associated with drug use. The ASI provides a quantitative, time-based assessment of problem severity in the following areas: alcohol use, drug use, and employment, medical, legal, family, social, and psychological functioning. The information obtained in this interview is quite useful for developing treatment plans that include lifestyle change goals.

A practical needs assessment questionnaire (developed in our clinic) is used to determine whether the patient has any pressing needs or crises that may interfere with initial treatment engagement (e.g., housing, legal, transportation, or child care). The intake worker asks specific questions regarding current housing, child care, legal circumstances, medical issues, and other matters that might been of current and serious concern to the client. Detailed information is collected on any identified crisis. The rationale here is to identify matters that may need immediate clinical attention.

If it appears that a medication is indicated, initial steps are taken after the initial intake assessment toward implementing the relevant medical protocols. With the cocaine-dependent population, we routinely use a regimen of clinic-monitored disulfiram therapy to address problem drinking, which also reduces cocaine use (22). More recently, we are often using a regimen of clinic-monitored naltrexone therapy as the prevalence of prescription opioid use has increased.

PRETREATMENT ISSUES

Motivation

Within an operant framework, motivation is not thought of as a characteristic of the patient per se but rather as a product of current and past reinforcement contingencies tempered by potential individual differences in delay discounting, educational attainment, and other matters that may influence behavioral choice (2,10). The overarching focus of the interventions is to directly ensure the availability of sufficient reinforcement to promote and sustain therapeutic change. Following, we discuss how that is accomplished.

Rationale for Choice of Treatment

The historical and conceptual background information described previously provides the overarching rationale for the use of CM and CRA interventions. CM and CRA have the potential to be useful with virtually any type of SUDs. There is no minimal or maximal intensity or duration of CM or CRA, and thus there is a great deal of flexibility in terms of adapting them to particular forms of SUDs and special populations.

Selection and Preparation of Patients

As noted, we know of no particular type of SUD patient for whom CM or CRA is contraindicated. Both have been used effectively across a wide spectrum of patient populations and types of SUDs. Both interventions require a detailed and careful patient orientation. With CM, it is quite common to have patients sign a written contract stipulating all aspects of the CM arrangement so as to avoid any confusion about the contingencies. Brief tests are also commonly administered to ensure that patients understand the contingencies. The vocabulary and other information contained in the contract and tests should be prepared with the potential intellectual limitations of the patient population in mind and plans to surmount potential individual difficulties. For example, reading problems are common among patients with SUDs, and certain patients may need to have written materials read aloud to them.

Therapist Characteristics

Therapists typically do not manage CM programs owing to the detailed record keeping involved and the need to biochemically verify abstinence, though there are exceptions. Thus, this section largely pertains to characteristics of CRA therapists. CRA is a manually based intervention that minimizes the influence of therapist characteristics on outcome. In the series of studies examining CRA + voucher treatment of cocaine dependence, for example, there have not been any significant therapist effects on outcome noted.

To implement CRA effectively, therapists need to be directive but also flexible, which we believe facilitates treatment retention and progress toward achieving treatment goals. Particularly in the early stages of treatment, therapists try to work around patient schedules and generally make participation in treatment convenient to the patient. Therapists try to be flexible with regard to tardiness to sessions, early departure from sessions, and the time of day that sessions are scheduled and will meet with patients outside the office if necessary. With especially difficult patients, improvements in these areas can be worked on as part of the treatment plan. CRA therapists must exhibit appropriate empathy and good listening skills. They need to convey a sincere understanding of the patient’s situation and its inherent difficulties. Throughout treatment, therapists avoid making value judgments and, instead, exhibit genuine empathy and consideration for the difficult challenges that patients face.

CRA requires that therapists and patients develop an active, make-it-happen attitude throughout treatment. Therapists must have good organizational skills, which are important for developing, implementing, monitoring, and adapting treatment plans. Problem-solving skills also are important. Within ethical boundaries, therapists must be committed to doing what it takes to facilitate lifestyle changes on the part of patients. For example, therapists often accompany patients to appointments or job interviews. They initiate recreational activities with patients and schedule sessions at different times of day to accomplish specific goals. They have patients make phone calls from their office. They search newspapers for job possibilities or ideas for healthy recreational activities in which patients might be able to participate. Without question, the amount of direct support that CRA therapists provide to patients can represent a rather significant departure from more traditional forms of substance abuse counseling. However, in CRA, these therapeutic efforts are deemed to be very important for at least three reasons. First, while patients may have the aptitude, they may simply lack certain skills to accomplish important tasks (e.g., effective job searching). Second, early in treatment, patients may lack the requisite reinforcement history (i.e., motivation) with certain healthy activities (e.g., attending the local YMCA) to carry through on assigned tasks in the absence of the therapist being present to prompt the response and provide social reinforcement for completing the task. Third, patients may lack the necessary material resources (e.g., transportation or materials for résumé preparation) to complete a task in a timely manner. CRA therapists are committed to overcoming such deficiencies in skills, motivation, or resources in order to facilitate patient movement in the direction of a healthier, non–drug-abusing lifestyle.

TREATMENT AND TECHNIQUE

In this section, we describe basic elements of CM and CRA interventions using the CRA + voucher treatment for cocaine dependence for illustration purposes.

Contingency Management

The efficacy of CM interventions is very much dependent on how they are structured and implemented. Following, we provide a brief description of a voucher-based CM intervention. Next, we outline 10 features of CM interventions that are important to their efficacy (23).

In the voucher-based CM program, patients sign a written contract stipulating all aspects of the CM interventions. Vouchers exchangeable for retail items are earned contingent on cocaine-negative results in thrice-weekly urine toxicology testing. The program is 12 weeks in duration (on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday). The first cocaine-negative specimen earns a voucher worth $2.50 in purchasing power. The value of each subsequent consecutive cocaine-negative specimen increases by $1.25. The equivalent of a $10 bonus is provided for each three consecutive cocaine-negative specimens. The intent of the escalating magnitude of reinforcement and bonuses is to reinforce continuous cocaine abstinence. A cocaine-positive specimen or failure to submit a scheduled specimen resets the value of vouchers back to the initial $2.50 value. This reset feature is designed to punish relapse to cocaine use after a period of sustained abstinence, with the intensity of the punishment tied directly to the length of sustained abstinence that would be broken. In order to provide patients with a reason to continue abstaining from drug use after a reset, submission of five consecutive cocaine-negative specimens after a cocaine-positive specimen returns the value of points to where they were prior to the reset. Points cannot be lost once earned. If someone is continuously abstinent throughout the 12-week intervention, total earnings would be approximately $997.50. However, because most patients are unable to sustain abstinence throughout the intervention, the average earning is usually about half that maximal amount.

The voucher CM intervention contains most features important to effective CM. First, as was noted, the details of the intervention are carefully explained to patients in the form of a written contract prior to beginning treatment. Second, the response being targeted by the CM intervention—cocaine abstinence—is defined in objective terms (i.e., cocaine-negative urine toxicology results). Third, the methods for verifying that the target response occurred are well specified and objective (urine toxicology testing). Fourth, the schedule for monitoring progress is well specified (each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday). Fifth, the schedule is designed to include frequent opportunities for patients to experience the programmed consequences (thrice weekly). Sixth, the duration of the intervention is stipulated in advance (12 weeks). Seventh, the intervention is focused on a single target (cocaine abstinence). CM interventions that focus on a single target on average produce larger treatment effects than those that target multiple targets (e.g., abstinence from multiple substances) (24). Eighth, the consequences that will follow success and failure to emit the target response are clear (consequences including voucher reinforcement schedule carefully detailed). Ninth, there is a minimal delay in delivering designated consequences (urine specimens are analyzed on-site, and vouchers earned are delivered immediately after testing). Delivering the consequence on the same day that occurrence of the target response is verified produces larger treatment effects than delivering the consequence at a later time (24). Tenth, the magnitude of reinforcement that can be earned is relatively substantial (maximal total earnings = $997.50). Larger value incentives on average produce larger treatment effects (24).

Community Reinforcement Approach

The CRA component of the CRA + voucher treatment has seven elements. First, patients are instructed in how to recognize antecedents and consequences of their cocaine use; that is, how to functionally analyze their cocaine use. They are also instructed in how to use that information to reduce the probability of using cocaine. A twofold message is conveyed to the patient: (i) His or her cocaine use is orderly behavior that is more likely to occur under certain circumstances than others, and (ii) by learning to identify the circumstances that affect one’s cocaine use, plans can be developed and implemented to reduce the likelihood of future cocaine use. In conjunction with functional analysis, patients are taught self-management plans for using the information revealed in the functional analyses to decrease the chances of future cocaine use. Patients are counseled to restructure their daily activities in order to minimize contact with known antecedents of cocaine use, to find alternatives to the positive consequences of cocaine use, and to make explicit the negative consequences of cocaine use.

Second, developing a new social network that will support a healthier lifestyle and getting involved with recreational activities that are enjoyable and do not involve cocaine or other drug use is addressed with all patients. Systematically developing and maintaining contacts with “safe” social networks and participation in “safe” recreational activities remains a high priority throughout treatment for the vast majority of patients. Specific treatment goals are set, and weekly progress on specific goals is monitored. Clearly, plans for developing healthy social networks and recreational activities must be individualized depending on the circumstances, skills, and interests of the patient. For those patients who are willing to participate, self-help groups (Alcoholics or Narcotics Anonymous) can be an effective way to develop a new network of associates who will support a sober lifestyle.

Third, various other forms of individualized skills training are provided, usually to address some specific skill deficit that may influence directly or indirectly a patient’s risk for cocaine use (e.g., time management, problem-solving, assertiveness training, social skills training, and mood management). For example, essential to success with the self-management skills and social/recreational goals discussed is some level of time-management skills. As another example, we implement protocols on controlling depression with those patients whose depression continues after discontinuing cocaine use (25,26).

Fourth, unemployed patients are offered Job Club, which is an efficacious method for assisting chronically unemployed individuals obtain employment (Job Club manual, Azrin and Besalel) (27). The majority of patients who seek treatment for cocaine dependence are unemployed, so this is a service that we offer many of our patients. For others, we assist in pursuing educational goals or new career paths.

Fifth, patients with romantic partners who are not drug abusers are offered behavioral couple therapy, which is an intervention designed to teach couples positive communication skills and how to negotiate reciprocal contracts for desired changes in each other’s behavior (28). We attempt to deliver relationship counseling across eight sessions, with the first four sessions delivered across consecutive weeks and the next four delivered on alternating weeks.

Sixth, human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) education is provided to all clients in the early stages of treatment, along with counseling directed at addressing any specific needs or risk behavior of the individual patient (29). We address with all clients the potential for acquiring HIV/AIDS from sharing injection equipment and through sexual activity. This involves at least two sessions. First, patients complete an HIV/AIDS knowledge test. They next watch and discuss with their therapist a video on HIV/AIDS. Patients are also provided HIV/AIDS prevention pamphlets and free condoms if desired. The HIV/ AIDS knowledge test is repeated, and any remaining errors are discussed and resolved. Last, patients are given information about testing for HIV and hepatitis B and C and are encouraged to get tested. Those interested in being tested are assisted in scheduling an appointment to do so.

Seventh, all who meet diagnostic criteria for alcohol dependence or report that alcohol use is involved in their use of cocaine are offered disulfiram therapy, which is an integral part of the CRA treatment for alcoholism (30) and decreases alcohol and cocaine use in clients dependent on both substances (22). Patients generally ingest a 250-mg daily dose under clinic staff observation on urinalysis test days and, when possible, under the observation of a significant other (SO) on the other days. Disulfiram therapy is only effective when implemented with procedures to monitor compliance with the recommended dosing regimen. We find that having staff monitor compliance on days that patients attend clinic works very well. Having an SO monitor compliance on the other days can work well if an appropriate person is available to do so at the frequency needed. When that is not possible, we sometimes adopt a practice of having the client ingest a larger dose (500 mg) on days when the patient reports to the clinic and skip dosing on the intervening days.

Use of substances other than tobacco and caffeine is discouraged as well via CRA therapy. Anyone who meets criteria for physical dependence on opiates is referred to an adjoining service located within our clinic for methadone or other opioid replacement therapy (31). We recommend marijuana abstinence because of the problems associated with its abuse, but have found no evidence that marijuana use or dependence adversely affects treatment for cocaine dependence (32). As important, we never dismiss or refuse to treat a patient owing to other drug use. We recommend cessation of tobacco use but typically have not done so during the course of treatment for cocaine dependence. That practice is changing as evidence is suggesting that smoking cessation can be successfully integrated into simultaneous treatment for other SUDs.

Upon completion of the 24 weeks of treatment, patients are encouraged to participate in 6 months of aftercare in our clinic, which involves at least once-monthly brief therapy sessions and urine toxicology screening. More frequent clinic contact is recommended if the therapist or patients deem it necessary.

EMPIRICAL SUPPORT

Contingency Management Interventions

Initial Contingency Management Studies

Among the most impressive of the early CM studies on SUDs was a randomized controlled trial conducted with 20 chronic public drunkenness offenders (33). Subjects randomly assigned to the CM group earned housing, employment, medical care, and meals based on sobriety (measured by direct staff observation or blood alcohol level [BAL] of < 0.01%), and those in the control group received the same goods and services independent of sobriety status. The intervention produced a fivefold decrease in arrests for subjects in the CM group and no or minimal change for the control group.

Another early approach to treating alcohol use disorders with CM involved reinforcing disulfiram treatment compliance. At least three experimental reports support the efficacy of CM for increasing disulfiram compliance in methadone-maintained patients with alcohol use disorders (34–36). For example, in one well-controlled study (36), alcoholic methadone patients whose daily methadone doses were contingent upon compliance with disulfiram spent 2% of study days drinking, as compared to 21% for the noncontingent control group. Similar results were reported using a controlled case study design (34).

Despite these impressive results, the use of CM to treat primary alcohol use disorders has largely failed to gain a foothold among the alcohol research or clinical communities. One obstacle is that objectively monitoring alcohol intake using BALs provides evidence about use only during the few hours preceding the test. Considering that alcohol often is abused in an episodic or binge manner, the absence of a biologic marker with a longer detection duration makes it difficult to reinforce or punish alcohol use. There is some evidence that newer technologies such as an ethyl glucuronide alcohol biomarker may surmount this long-standing problem (37). The earlier reports such as those by Miller (33) also illustrate that this difficulty can be surmounted by relying on a combination of observations by individuals in the subject’s natural environment and randomly scheduled BALs. Alternatively, the studies already described illustrate how reinforcing compliance with disulfiram or with other treatment goals can reduce drinking when the contingencies are managed systematically. Overall, CM appears to have more to offer alcohol treatment than currently is being realized. Worth noting is that while the work begun using CM to reinforce disulfiram compliance has not been continued in any programmatic manner, the concept was successfully extended to reinforcing naltrexone compliance among patients with opioid use disorders (38,39) as well as reinforcing adherence to antiretroviral therapies among HIV-positive patients with SUDs (40).

Developing Contingency Management as a Treatment for Illicit Drug Use Disorders

Though research on CM among those with primary alcohol use disorders was having difficulty gaining a foothold during the 1970s and 1980s, a concerted body of work emerged on the use of CM to treat illicit drug use. That work was almost exclusively conducted with patients enrolled in methadone treatment for opioid use disorders.

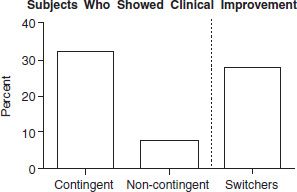

Though methadone and related substitution therapies are effective at eliminating the use of illicit opioids, a subset of patients continue abusing other nonopioid drugs. A commonly used reinforcer in this area of CM research is the medication take-home privilege, where an extra daily dose of opioid medication is dispensed to the patient for ingestion at home on the following day, thereby granting the patient a break from the grind of having to travel daily to the clinic to ingest the medication under staff supervision (41–45). For example, in what is probably the most rigorous evaluation of the use of contingent medication take-home privileges, Stitzer et al. (45) examined the use of take-home incentives among 54 newly admitted methadone maintenance patients. Half the group received take-home privileges contingent on abstinence from illicit drug use, while the other half received the take-home doses noncontingently. Overall, 32% of the contingent patients achieved sustained periods of abstinence during the intervention (mean, 9.4 weeks; range, 5 to 15 weeks), compared with approximately 10% in the control group (Fig. 58-1). The beneficial effect of contingent take-home delivery was replicated within the group of noncontingent patients who switched over to the contingent intervention after their 6-month evaluation in the main study (partial crossover design).

FIGURE 58-1 Improvement in urine test results. Percentages of subjects whose urine test results improved 10% or more from baseline to intervention periods and submitted at least 12 consecutive drug-free tests during the intervention period are shown for the original contingent and noncontingent take-home groups and also for the group of non-contingent subjects who received delayed exposure to the contingent protocol later in treatment. (Reprinted from Stitzer ML, Iguchi MY, Felch LJ. Contingent take-home incentive: effects on drug use of methadone maintenance patients. J Consult Clin Psychol 1992;60:927–934, with permission.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree