Primary tumor (T)

TX

Primary tumor cannot be assessed

T0

No evidence of primary tumor

a

T2

Organ-confined disease

T2a

Unilateral disease, one-half of one lobe or less

T2b

Unilateral disease, involving more than one-half of one lobe, but not both lobes

T2c

Bilateral disease

T3

Extraprostatic extension

T3a

Extracapsular extension or microscopic bladder neck invasion

T3b

Seminal vesicle invasion

T4

Invasion of rectum levator muscles and/or pelvic wall

Regional lymph nodes (N)

NX

Regional lymph nodes not sampled

N0

No positive regional lymph nodes

N1

Metastasis in regional lymph node(s)

Distant metastasis (M)

M0

No distant metastasis

M1

Distant metastasis

M1a

Nonregional lymph node(s)

M1b

Bone(s)

M1c

Other site(s) with or without bone disease

Group | T | N | M | PSA | Gleason score (GS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

I | T1a–c | N0 | M0 | PSA < 10 | GS £ 6 |

T2a | N0 | M0 | PSA < 10 | GS £ 6 | |

T1–2a | N0 | M0 | PSA x | GS x | |

IIA | T1a–c | N0 | M0 | PSA < 20 | GS 7 |

T1a–c | N0 | M0 | PSA ≥ 10 < 20 | GS £ 6 | |

T2a | N0 | M0 | PSA < 20 | GS £ 7 | |

T2b | N0 | M0 | PSA < 20 | GS £ 7 | |

T2b | N0 | M0 | PSA x | GS x | |

IIB | T2c | N0 | M0 | Any PSA | Any GS |

T1–2 | N0 | M0 | PSA ≥ 20 | Any GS | |

T1–2 | N0 | M0 | Any PSA | GS ³ 8 | |

III | T3a–b | N0 | M0 | Any PSA | Any GS |

IV | T4 | N0 | M0 | Any PSA | Any GS |

Any T | N1 | M0 | Any PSA | Any GS | |

Any T | Any N | M1 | Any PSA | Any GS |

Several modifications have been made over time to the TNM staging system in an attempt to improve the uniformity of patient evaluation and to maintain a clinically relevant classification [2]. The ongoing critical evaluation of this staging system will indeed incorporate new evidence-based factors to secure future refinements to PCA staging. In the most recent AJCC text, Gleason score (GS) and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) have been incorporated in the anatomic stage/prognostic groups (Table 3.2) [1].

Clinical T Staging

Accurate clinical staging is crucial to provide adequate counseling for therapeutic treatment options, since risk stratification allows prediction of patient outcomes based on cancer characteristics. Clinical staging (cTNM) is performed by the urologist or referring physician during the initial evaluation of the patient, or when pathologic classification is not possible. All parameters available before the first definitive treatment may be used for clinical staging and remain unchanged even if pathologic findings differ. Primary tumor assessment includes digital rectal examination (DRE), transrectal ultrasound (TRUS), and histologic confirmation of PCA by prostate biopsy. DRE has been a cornerstone of staging; however, DRE is insufficient for determining accurate stage and extent of disease, since approximately half of tumors are understaged by DRE alone [3].

Imaging modalities such as transrectal ultrasound (TRUS), CT, and MRI have also been utilized to improve staging accuracy. Transrectal ultrasonography of the prostate is the most commonly used imaging technique for staging as it is routinely used to direct initial prostate biopsies. Although the accuracy of TRUS for clinical staging has been questioned, in the current era of PSA screening with lower-risk tumors, TRUS may supplant DRE for the clinical staging of nonpalpable prostate cancer and add unique and important information when considering treatment options for men with early-stage prostate cancer [4] .

The AJCC clinical staging stratifies patients according to the method of tumor detection, separating nonpalpable radiologically occult “incidental” prostate cancers detected during transurethral resection of the prostate for clinically benign prostatic hyperplasia (classified as stage cT1a or cT1b) from palpable cancers detected by DRE or imaging (classified as cT2a/cT2b for a unilateral palpable nodule and/or unilateral lesion on imaging). This staging system also recognizes nonpalpable cancer detected by an elevated serum PSA level or an abnormal TRUS image (stage T1c). It is generally accepted that biopsy results should not be incorporated into clinical stage assignment, otherwise, by definition no patient would be assigned to clinical T1c stage.

Substaging of clinical stage T2 prostate cancers is largely based on the extent of the abnormality palpated during a DRE or shown during TRUS in each half of the gland. Tumor extending beyond the boundary of the prostate gland is classified as stage T3; prostate cancer fixed or invading adjacent structures other than seminal vesicles, such as external sphincter, rectum, bladder , levator muscles, and/or pelvic wall is equivalent to clinical stage T4.

Clinical stage is included as a component of several frequently cited nomograms and prognostic tools [5]. However, in contemporary multivariable models incorporating powerful predictors such as PSA , GS, and percentage of positive biopsy cores, it appears that clinical staging criteria offer limited independent prognostic information in predicting recurrence of localized prostate cancer among radical prostatectomy patients [6–8].

Pathologic T Staging

Pathologic stage (pTNM) at radical prostatectomy remains one of the most important and accurate assignments, essential not only in determining the most appropriate choice of therapy of individual patients, but also in predicting the likelihood of local and distant disease recurrence. It is completely dependent on the pathologist’s handling and reporting of the surgically resected specimen. Methods for the grossing and sampling of radical prostatectomy specimens have evolved over the years [9]. More recently the 2009 consensus conference sponsored by the International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) made recommendations regarding the standardization of pathology reporting of radical prostatectomy specimens and addressed controversies related to definitions of features such as extraprostatic extension (EPE), bladder neck involvement, and seminal vesicle invasion (SVI) [9–13] .

Pathologic Stage T2

The TNM 2002 staging system subdivided pT2 disease into three categories as determined by involvement of less than one half of one side (pT2a), more than one half of one side (pT2b), and both sides of the prostate gland (pT2c), respectively, to mirror the clinical substaging and allow direct comparison of both. In contrast to clinical substaging of T2 cancers, pathological substaging does not convey prognostic information. Stage pT2 PCA seems to represent a homogeneous group with an overall excellent prognosis and a 5-year biochemical progression-free survival (BPFS) over 90 %. Several recent studies, including very large cohorts of patients, have failed to demonstrate a significant prognostic difference for intermediate-term outcomes between pathological stage T2a versus T2b versus T2c disease [14, 15], suggesting that the pathological T2 substages may not confer any prognostic value for predicting biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. The 2009 ISUP consensus conference recommendation was that reporting of pT2 substages should, at present, be optional [13].

Pathologic Stage T3

Stage T3 disease is subdivided into two categories, as determined by the presence of EPE in any location (pT3a) and presence of SVI with or without EPE (pT3b).

Extraprostatic Extension (pT3a)

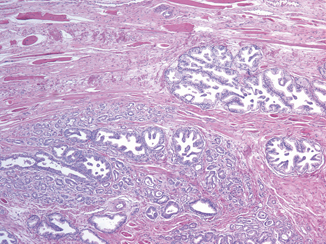

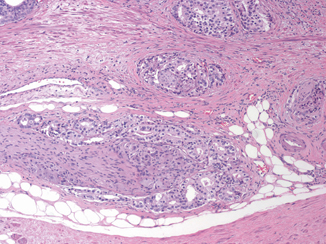

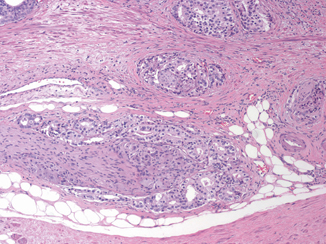

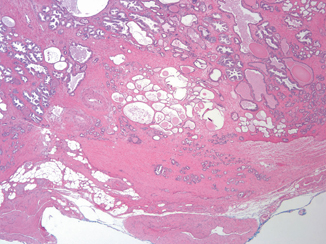

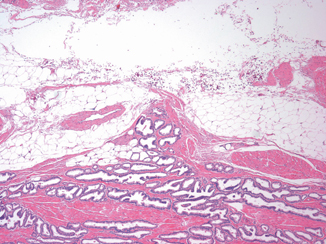

EPE is the preferred terminology to indicate the extension of tumor beyond the confines of the prostate gland. However, the definition is complicated by the anatomy of the gland that in many areas does not possess a well-defined histologic capsule, particularly in the apical region and along the anterior and posterior surface. Tumor admixed with periprostatic fat is the most easily recognized manifestation of EPE (Fig. 3.1). Current definitions of EPE include “tumor abutting on or admixed with fat” and “tumor involving loose connective tissue or perineural spaces of the neurovascular bundles” even in the absence of direct contact between tumor cells and adipocytes (Fig. 3.2).

Fig. 3.1

Prostate cancer admixed with periprostatic fat is the most easily recognized manifestation of extraprostatic extension ( × 10)

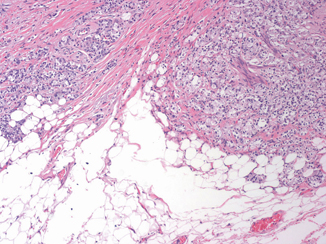

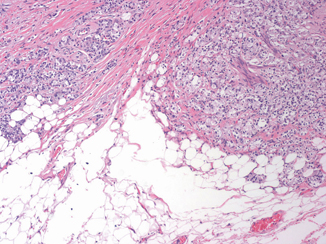

Fig. 3.2

Extraprostatic extension includes prostate cancer involving perineural spaces of the neurovascular bundle ( × 10)

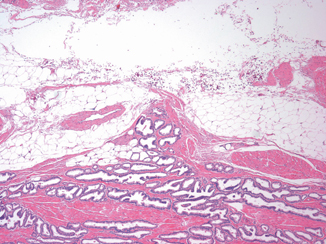

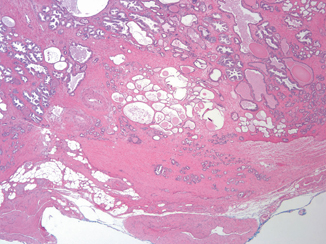

Posterolaterally, EPE may also be recognized as a distinct tumor nodule within desmoplastic stroma that bulges beyond the normal rounded contour of the gland (Fig. 3.3) or beyond the condensed smooth muscle of the prostate. Scanning magnification should be used to look for a protuberance of tumor from the normal smooth contour of the prostate , followed by higher magnification to confirm the absence of condensed smooth muscle in the desmoplastic stroma [11]. Although in the apex, anterior, and bladder neck regions, there is a paucity of fat and the histological boundary of the prostate is poorly defined, EPE may also be identified anteriorly when tumor touches an inked surgical margin, where benign glands have not been similarly cut across or when malignant glands extend beyond the contour of the normal glandular prostate (Fig. 3.4).

Fig. 3.3

A distinct tumor nodule within desmoplastic stroma bulging beyond the normal rounded contour of the gland represents another example of extraprostatic extension ( × 2)

Fig. 3.4

Anterior extraprostatic extension with malignant glands extending beyond the normal contour of the prostate gland ( × 4)

Finding malignant glands within striated muscle in the apex does not constitute EPE, since benign glands are frequently admixed with striated muscle in this location (Fig. 3.5).