110

CHAPTER OUTLINE

The principle of autonomy is enshrined in the constitution, and US courts have repeatedly confirmed Americans’ right to make decisions for themselves, including decisions about which information about their health care may be disclosed and to whom. Whenever a physician asks a patient to sign an “informed consent” agreement or to consent to disclosure of certain information, he or she is affirming that the patient has the right to make decisions about his or her medical care.1

INFORMED CONSENT

Informed consent has two components: information and voluntariness. First, the patient’s decision to undergo a course of treatment must be based on knowledge and competency. The physician must give the patient the kind and amount of information the patient needs to make an intelligent (“informed”) choice, and the patient must be capable of understanding the information and making a decision. Second, the patient’s decision must be voluntary—that is, a product of his or her free will (1).

Information

The physician is obligated to give the patient all the information he or she needs to make a decision (2). This information should include the physician’s opinion of the patient’s diagnosis, an outline of the available treatment alternatives, a description of what each alternative involves (including its benefits and risks), an explanation of the consequences should the patient decline treatment altogether, and responses to the patient’s questions. Often, the physician also helps the patient evaluate the treatment alternatives in accordance with the patient’s values, hopes, and fears.

Competency (Decisional Capacity)

The concept of informed consent is based on the assumption that the patient has the capacity to make rational decisions (referred to as “decisional capacity”). Decisional capacity is defined as a state in which a patient is able to understand the physician’s explanation of the diagnosis, prognosis, treatment alternatives, and likely outcome if treatment is refused, and is able to go through the complex process of assessing that information in accordance with his or her personal system of values. Most patients have decisional capacity. However, the physician may encounter questions about decisional capacity in dealing with two groups: adolescents and older adults.

Special Issues in Dealing with Adolescents

The situation is somewhat different for adolescents because they do not have the legal status of full-fledged adults (3). There are certain decisions that society will not allow them to make, for example, below a certain age—which varies by state and by issue—adolescents must attend school, may not marry without parental consent, may not drive, and cannot sign binding contracts (4) (see Section 13 for a more detailed discussion of how this affects adolescents’ right to consent to treatment). Nevertheless, in common law, there is no minimum age at which individuals are able to consent to medical treatment and no age below which they are unable to consent. Adolescents’ right to self-determination is based on their ability to understand and appreciate the information relevant to the medical decision and on their ability to consent voluntarily and freely. There is a consensus in the literature that, around age 14 years, adolescents have the cognitive ability to understand information necessary for consent (5). However, there are limited empirical data regarding adolescents’ ability to appreciate the information and to make a voluntary decision.

In more than half the states, adolescents have the right to consent to screening, assessment, or treatment for substance use disorders.2 In other states, a parent must be notified of and/or consent to such care. In states that do not require parental consent, the physician has no ethical dilemma; he or she can provide whatever treatment is appropriate and to which the adolescent patient consents. In such states, the physician should involve adolescents in the consent process to the extent possible, assessing their capacity to consent to treatment on an individual basis, recognizing that such capacity may evolve as the adolescent’s cognitive capacities and values mature (5).

It is in those states that require parental consent or notification that the physician sometimes encounters a complex ethical quandary. The difficulty arises when an adolescent who seeks assessment or treatment refuses to permit communication with a parent.

If the physician believes that the adolescent does need treatment, he or she has three choices:

Option 1. Treat the Adolescent Without Consulting a Parent

The physician who treats an adolescent without parental consent or notification is acting in accordance with the ethical principles of putting the patient’s health first and respecting the patient’s autonomy (and privacy) but may be violating the law. Although violation of the parental consent/notification law most likely is not a criminal offense, it could put the physician’s professional license at risk or expose him or her to a lawsuit by the adolescent’s parents. It is unlikely, however, that a physician treating an adolescent would be faced with either eventuality if the treatment provided is not controversial or intrusive, does not put the adolescent at risk, and is carried out in a responsible, nonnegligent manner. In such circumstances, it would be difficult for a parent (or licensing authority) to show that any harm was done. This is particularly true if the physician made a reasoned decision and acted in good faith and out of concern for the adolescent. Contrary to popular belief, most lawyers do not chase after cases that are complex, time consuming, expensive, and difficult to win. Convincing an attorney to take on such a case would not be easy.

The physician who is considering whether to offer treatment without parental consent or notification in a state that requires it should consider the following factors.

■ The adolescent’s age. Society accords adolescents more autonomy as they get older. A physician who might decline to treat a 14-year-old patient without parental consent in a state that requires it might have fewer qualms about treating a 17-year-old patient in similar circumstances.

■ The adolescent’s maturity. Chronologic age clearly is not the only measure. There are 14-year-olds who have maturity beyond their years and emotionally immature 17-year-olds with poor social skills and reasoning ability.

■ The adolescent’s family situation. Adolescents in need of addictive disorder treatment may be estranged from their families. Those who refuse to permit parental notification may have good reason to do so. Forcing them to involve parents who have failed them is neither ethical nor a good clinical practice. Reconciliation with the family may be vital to an adolescent’s recovery, but circumstances may dictate that it be abandoned or postponed to a later stage of treatment.

■ The severity of the adolescent’s addictive disorder and the danger it poses to his or her life or health.

■ The kind of treatment to be provided. The more intrusive and intensive the proposed treatment, the more risk the physician assumes in treating an adolescent without parental consent. For example, a physician offering an outpatient course of treatment is on firmer ground than one proposing intensive outpatient or residential treatment.

■ The physician’s possible liability for refusing to treat the patient. State law may impose a duty to treat patients in need.

■ The financial consequences. If the physician treats an adolescent without parental consent, he or she may not be paid.

Option 2: Try to Obtain Consent to Treatment from the Adolescent’s Parent

Calling the parent and treating the adolescent comply with the letter of state law and are in accordance with the ethical principle that puts the patient’s health first. However, it clearly violates the adolescent’s right to privacy. Moreover, the federal confidentiality rules complicate this choice. If the physician is subject to the federal confidentiality rules, he or she is prohibited from contacting a parent unless the adolescent consents.

The sole exception allows a treatment program director to contact a parent when the life or physical well-being of an adolescent is threatened.

Federal confidentiality regulations prohibit physicians and others who provide alcohol and drug screening, assessment, and treatment from communicating with anyone, including a parent, unless the adolescent consents. The sole exception allows the director of an addiction treatment program to communicate “facts relevant to reducing a threat to the life or physical well-being of the (adolescent seeking services) or any other individual to the minor’s parent, guardian, or other person authorized under state law to act in the minor’s behalf, when the program director believes that the adolescent, because of extreme youth or mental or physical condition, lacks the capacity to decide rationally whether to consent to the notification of a parent or guardian,” or because “The program director believes the disclosure to a parent or guardian is necessary to cope with a substantial threat to the life or physical well-being of the adolescent or someone else” (42 CFR §§2.14(c) and (d)).

Option 3: Refuse to Treat the Adolescent

Refusing to treat the adolescent adheres to the letter of state laws that consider adolescents incompetent to make medical decisions, and it shows respect for the patient’s privacy, but it may violate the ethical principle that requires the physician to put the patient’s interests first. In some states, it also violates a law requiring physicians to treat patients in medical need.

Special Issues in Treating Older Adults

Most older adults are fully capable of understanding medical information, weighing treatment alternatives, and making and articulating decisions (6). However, a small percentage of older patients clearly are incapable of participating in a decision-making process. In such cases, the older adult may have signed a health care proxy or may have a court-appointed guardian who is authorized to make such decisions (7).

The difficulty arises when a physician is screening or assessing an older adult whose mental capacity lies between those two points on the continuum. The patient may have fluctuating capacity, with “good days” and “bad days,” or periods of greater or lesser alertness depending on the time of day. The patient’s condition may be transient or deteriorating. Diminished capacity may affect some parts of his or her ability to comprehend information and make complex decisions, but not others.

In caring for an older adult patient whose decisional capacity is less than optimal, how can the physician help the patient to understand the information presented, appreciate the implications of each alternative treatment, and make a “rational” decision, based on the patient’s best interests? And what can the physician do if the patient appears not to be competent to make his or her own health care decisions? Although there are no easy answers to these questions, there are several possible approaches.

Present Information Carefully

The physician can help the patient who appears to have diminished capacity through a gradual information- gathering and decision-making process. Information should be presented in a way that allows the patient to absorb it gradually, clarify and restate information as necessary, and summarize the issues at regular intervals. Each alternative approach to care and its consequences should be laid out and examined separately. Finally, the physician can help the patient identify his or her values and link those values to the alternatives. By helping the patient narrow his or her focus and then proceeding step by step, the physician may be assured that the patient has understood the choices and acted in his or her own best interests.

Enlist the Help of a Mental Health Professional or Other Specialist

If helping the patient through a process of gradual information gathering and decision making is not working, the physician can suggest that the physician and patient jointly consult a mental health professional or other physician who is familiar with the patient’s history and who thus may have a better understanding of the obstacles to decision making. Or the physician could suggest a specialist (such as a geriatrician) who can help determine why the patient is having difficulty and whether he or she has the capacity to give informed consent.

Enlist the Help of Family or Close Friends

Another approach is for the physician to suggest that the patient call in a family member or close friend who can help organize the information and sort through the alternatives. Asking the patient who would be helpful could gain endorsement of this approach.

Consult a Family Member or Friend

If the patient cannot grasp the information or come to a decision, the physician might ask the patient to allow him to consult a family member or close friend. If the patient consents, the physician should lay out the concerns to the family member or friend. It may be that the patient already has planned for the possibility of incapacity and has signed a durable power of attorney or health care proxy.

Guardianship

A guardian is a person appointed by a court to manage some or all aspects of another person’s life. Anyone seeking appointment of a guardian must show the court that the individual is disabled in some way by disease, illness, or senility and that the disability prevents that individual from performing the tasks necessary to manage one or more areas of his or her life.

Each state handles guardianship proceedings differently, but some principles apply across the board: Guardianship is not an all-or-nothing state. Courts generally require that the person seeking appointment of a guardian proves the individual’s incapacity in a variety of tasks or areas. Courts can apply different standards to different life tasks— managing money, managing a household, making health care decisions, and entering contracts. A person can be found incompetent to make contracts and manage money but competent to make his or her own health care decisions (or vice versa) and the guardianship limited accordingly.

Guardianship limits the older adult’s autonomy and is an expensive process. It should be considered only as a last resort.

AGREEMENT TO TREATMENT

As part of the informed consent process, the physician should discuss the risks and benefits of treatment with the patient and, with appropriate consent of the patient, with family members, significant other(s), or a guardian. This type of discussion is best accompanied by a written agreement between the physician and patient addressing issues such as (a) alternative treatment options, (b) agreement to regular toxicologic testing for drugs of abuse and therapeutic drug levels (if available and indicated), and (c) the reasons for which treatment may be altered or discontinued (7).

The written treatment plan should describe the objectives that will be used to determine treatment success, such as freedom from intoxication, improved physical function, psychosocial function, and compliance, and should indicate whether any further diagnostic evaluations are planned, as well as counseling, psychiatric management, or other ancillary services.

The plan should be reviewed periodically. After treatment begins, the physician should adjust therapy to the individual medical needs of each patient. Treatment goals, other treatment modalities, or a rehabilitation program should be evaluated and discussed with the patient. If possible, every attempt should be made to involve significant others or immediate family members in the treatment process, with the patient’s consent (8).

The treatment plan also should specify contingencies for treatment failure (such as failure to comply with the treatment plan, abuse of other opioids, or evidence from a state Prescription Drug Monitoring Program or other reliable source that prescribed medications are not being taken).

CONFIDENTIALITY PROTECTIONS

Ensuring confidentiality is perhaps the strongest element in the foundation of a therapeutic relationship (9,10), in that patients must have reasonable assurance that what they say to a treatment professional is protected information. Moreover, medicine historically attaches a high value to patients’ privacy because it is critical that patients give their physicians accurate information. By affording privacy protections to medical information, society assures patients that they can discuss sensitive subjects with their physicians without worrying about what use others might make of such information.

Nevertheless, the right to privacy is not without limits, and understanding the purpose and implications of those limits frequently poses problems for physicians and other health care professionals (10). The nature of managed care requires more extensive justification for treatment, and the number of individuals who demand information about a patient’s care is growing. Additionally, the growing use of electronic health records and other computerized data can further jeopardize the concept of protected information.

It is the ethical responsibility of health care professionals to be honest with patients as to what data need to be reported to insurance companies and what information needs to be shared with other agencies or individuals. It is the legal responsibility of the provider to obtain consent for any information shared outside of the physician–patient relationship (9).

Basis of Confidentiality

Confidentiality is especially important when a patient has an addictive disorder because of the widespread perception that such persons are weak and/or morally impaired. For example, a patient considering treatment might be concerned that, if an insurer or Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) learns that his or her traumatic injuries are related to alcoholism, it will be difficult or impossible to obtain coverage for hospitalization costs or that his or her insurance will be canceled. Similarly, a patient may fear that his or her relationships with a spouse, parents, children, an employer, or friends would suffer if they learned about his or her problems with alcohol or drugs. If a patient has marital problems, information about an addictive disorder could have an effect on divorce or custody proceedings. A patient whose problem becomes known to his employer could lose an expected promotion or his or her job. Adverse consequences such as these can deter patients from admitting to problems with alcohol or drugs and from obtaining treatment for those problems.

As with consent, laws governing adolescent confidentiality vary from state to state, but there are federal guidelines and common law concepts that are applicable throughout the United States. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) also provides guidelines for confidential care to minors (11).

Physicians and other medical care providers also need to manage confidentiality issues in drug testing, billing of services, and medical records and to work with clinical administrative staff to clarify and implement policies to maintain confidentiality (12).

Federal Laws Governing Confidentiality

In the early 1970s, the Congress passed legislation to protect information about patients receiving treatment for substance use disorders and directed the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) to issue regulations protecting patients’ confidentiality. The law is codified at 42 U.S.C. §290dd-2. The implementing federal regulations, titled “Confidentiality of Alcohol and Drug Abuse Patient Records,” are contained in 42 CFR Part 2 (Volume 42 of the Code of Federal Regulations, Part 2). The federal rules permit disclosures in only nine limited circumstances:

1. When a patient signs a consent form that complies with the regulations’ requirements

2. When a disclosure does not identify the patient as an individual with a substance use disorder

3. When treatment staff consult among themselves

4. When the disclosure is to a “qualified service organization” that provides services to the patient

5. When there is a medical emergency

6. When the law requires reporting of child abuse or neglect

7. When a patient commits a crime at the treatment program or against its staff members

8. When the information is for research, audit, or evaluation purposes

9. When a court issues a special order authorizing disclosure

Federal confidentiality rules apply to almost all specialized treatment for substance use disorders in the United States. They prohibit staff and treatment personnel from disclosing any information (written or oral) about any applicant, patient, or former patient unless (a) the patient has consented in writing (on the form required by the regulations) or (b) another very limited exception specified in the regulations applies. The rules apply regardless of whether the individual seeking the information already has the information, has other ways of obtaining it, has official status, is authorized by state law, or has a subpoena or search warrant.

In many instances, federal law and regulations restrict communications more tightly than do either the physician– patient or the attorney–client privilege. Violations of the regulations are punishable by fines of up to $500 for a first offense and up to $5,000 for each subsequent offense (42 CFR §2.4).

Physicians who practice primary care probably are not subject to the provisions of 42 CFR Part 2. However, when a general care practice includes someone whose primary function is to provide treatment for substance use disorders and the practice benefits from “federal assistance,” it must comply with the federal rules for handling information about patients who have substance use disorders.

Although most primary care physicians are not subject to the federal rules, they are well advised to handle information about patients’ substance use disorders with great care. The best practice for those who are not required to follow the rules is voluntary compliance.

In 1996, the Congress passed another law, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, Public Law 104–191 (HIPAA), which mandated the establishment of standards for the privacy of “individually identifiable health information.” To carry out this mandate, the DHHS in 2000 issued a set of regulations governing patients’ privacy that apply to a wide range of “health care providers.” The HIPAA regulations appear in Volume 45 of the Code of Federal Regulations, Parts 160 and 164.

HIPAA regulations are not as restrictive as the requirements of 42 CFR Part 2. Practitioners who are subject to both sets of rules must follow the more restrictive federal standard.

State Laws Governing Confidentiality

State laws also afford some protection to medical information. Most physicians and patients think of these laws as the “physician–patient privilege.” Strictly speaking, the physician–patient privilege is a rule of evidence that governs whether a physician can be compelled to testify in court about a patient. However, in many states, the laws offer wider protection, and some states have special confidentiality laws that explicitly prohibit practitioners from divulging information about a patient without that patient’s consent. States often include such prohibitions in their professional licensing laws, which generally prohibit licensed professionals from divulging information about patients. Many also make unauthorized disclosures grounds for disciplinary action, including license revocation.

Each state has its own set of rules, which means that the scope of protection offered by state law varies widely. Whether a communication (or laboratory test result) is “privileged” or “protected” depends on a number of factors:

■ The type of professional holding the information and whether he or she is licensed or certified by the state. Most state laws do cover licensed physicians.

■ The context in which the information was communicated. Some states limit protection to information a patient communicates to a physician in private, in the course of a medical consultation, but do not protect information disclosed to a physician in the presence of a third party such as a spouse. Other states protect information the patient tells the physician when others are present as well as information the physician gains during private consultations or examination.

■ The circumstances in which “confidential” information will be or was disclosed. Some states protect medical information only when that information is sought in a court proceeding. If a physician divulges information about a patient in any other setting, the law does not recognize that there has been a violation of the patient’s right to privacy. Other states protect medical information in many different contexts.

■ How the right to privacy is enforced. Legal protection of medical information is useful only when it is backed by enforcement of the law.

Although enforcement actions remain relatively rare, states have the authority to discipline health professionals who violate patients’ privacy. They also can allow patients to sue physicians for damages over violations of patient privacy.

Exceptions to Confidentiality Requirements

Exceptions to any general rule protecting the confidentiality of medical information generally include the following:

■ Consent: All states permit physicians to disclose information if the patient consents, although states have different requirements regarding consent (e.g., in some states, it must be written, while in others, it can be oral). Some states require different consent forms for disclosures about different medical disorders. Of course, the patient can revoke his or her consent at any time.

■ Reporting child abuse and neglect: All states require physicians to report child abuse and neglect to child protective services, but again, states’ definitions of child abuse vary.

■ Reporting infectious diseases: All states require physicians to report certain infectious diseases to public health authorities, although states’ definitions of reportable diseases vary.

■ Duty to warn: Most states also require physicians to report a patient’s credible threat to harm others.

When Confidentiality Conflicts with Other Principles

Laws differ in defining whether a physician’s obligation is to the patient or another individual or class of individuals.

Employer versus Employee

To whom does a physician owe loyalty when treating a patient who has been referred by an employer as a condition of retaining a job? Is it to the employer who is relying on the physician to help the employee recover and remain (or return) to work? Or is it to the patient (the employee)? The employer likely will require reports from the physician on the patient’s progress in treatment. What should the physician do if the employee is not attending or adhering to the treatment plan? This question appears most starkly when the employee is in a safety-sensitive position and the physician is concerned that his or her behavior poses an immediate risk to other employees or to the public. To which ethical principle should the physician adhere: the obligation to safeguard the patient’s privacy or the obligation to protect those who might be harmed by the patient’s actions?

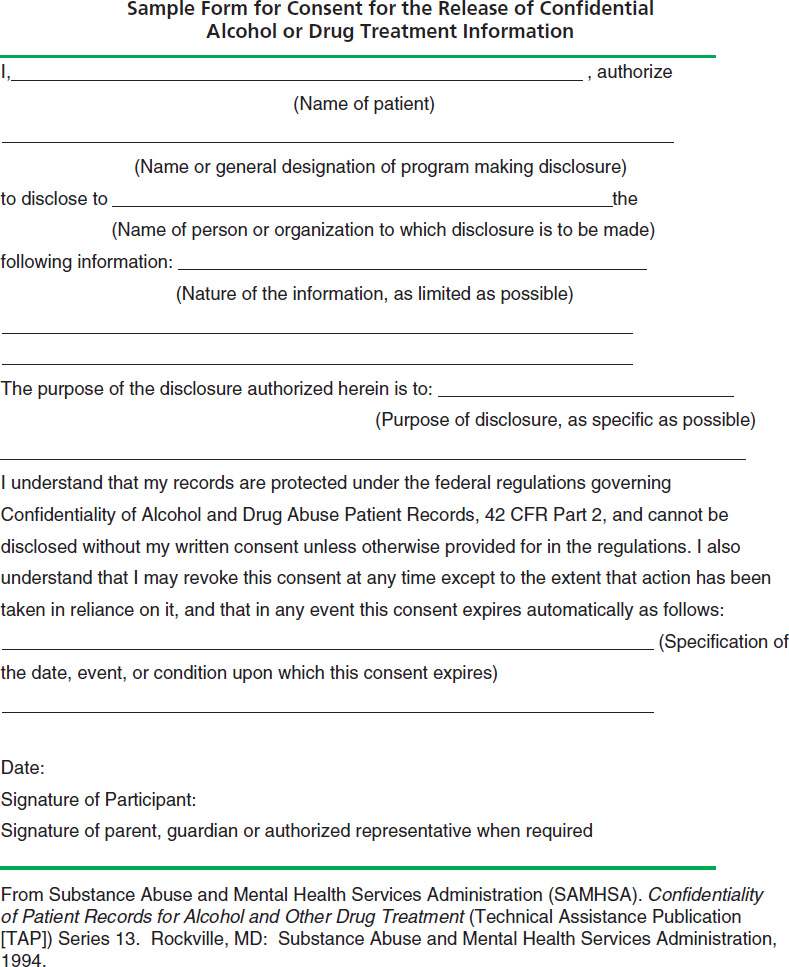

The best way to avoid having to grapple with this problem in an emergency (always a difficult and unpleasant experience) is to create agreed-upon ground rules before treatment begins. If an employer requires reports, the physician must have the patient sign a consent form authorizing communications with the employer and defining the kinds of information that will be reported (this agreement should be made part of the consent form) (Fig. 110-1). Of course, the employer also must be willing to accept whatever limitations the agreement places on the kinds of information to be provided.

FIGURE 110-1 Sample form for consent for the release of confidential alcohol or drug treatment information.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree