Complications of Adolescence

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, the student is expected to:

2. Describe the changes in the postural abnormalities kyphosis, lordosis, and scoliosis.

3. Discuss the bone infection osteomyelitis and the importance of early treatment.

4. Describe the effects of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.

5. Compare the eating disorders anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa.

6. Explain the cause and potential effects of acne.

7. Describe the disease infectious mononucleosis.

Key Terms

adhesions

amenorrhea

androgens

anemia

anomalies

arrhythmias

body mass index

caries

effusion

emaciated

epiphyseal plate or disc

esophagitis

glucose metabolism

gonadotropins

gonads

insulin resistance

lipoprotein metabolism

menarche

metabolic syndrome

metaphysis

monosomy

osteoporosis

periosteum

puberty

pustule

sebaceous

sebum

sinus

type 2 diabetes

Review of Changes During Adolescence

Adolescence is a time of major physiologic, psychological, and sociologic changes, a time of transition into adulthood. It is also a time when certain diseases, developmental or infectious, tend to develop. The period of adolescence is generally considered to begin with the development of secondary sex characteristics around the age of 10 to 12 years and to continue until physical growth is completed at about age 18. The term puberty indicates the onset of reproductive changes, beginning with the appearance of secondary sexual characteristics and the first menstrual cycle in females. Both the timing and the extent of change vary greatly among individuals. In recent years, perhaps because of improved nutrition, maturation has tended to occur at an earlier age.

The biologic changes typical of adolescence result primarily from hormonal activity stimulated by the hypothalamus and pituitary gland. Gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRh) from the hypothalamus stimulates and increases the release of gonadotropins from the pituitary. Gonadotropins (LH and FSH) support the further development of the ovaries and testes. In the female, the ovaries release ova and the sex hormones estrogen and progesterone, and in the male, the testes begin to produce sperm and to release testosterone. Although these sex hormones are produced in small quantities by the adrenal cortex during all stages of life, the larger quantities now available from the gonads are responsible for the unique types of growth and development that are characteristic of the teen years.

Linear growth is accelerated during the typical adolescent growth spurt. In most males the growth spurt occurs later than in females and usually lasts longer because epiphyseal closure is delayed in males. In recent generations both males and females have achieved a greater average height. Any growth retardation usually is apparent before adolescence, but if it is evident at this time it can be confirmed by x-rays illustrating an abnormally thin epiphyseal plate or disc. Other skeletal changes include the development of a broader pelvis in females and an increase in the width of the shoulders and chest in males. Because of the anabolic actions of the male sex hormones (androgens) or testosterone, males develop more skeletal muscle mass than females during puberty. This is obvious in the shoulder and chest areas. In a newer form of substance abuse, synthetic androgens, the “muscle-building” steroids, are taken by some adolescents to improve body image and athletic performance, without regard for dangerous side effects on the heart and liver. The growth changes of adolescence do not occur simultaneously. Limb growth occurs first, then hip and shoulder development, and increase in skeletal muscle mass is last. This is why the adolescent may appear awkward and gangly for a time until proportionate and complete maturation is accomplished.

Additional factors influencing growth during this period include nutrition, genetic factors, and activity levels. It is most important that calcium and vitamin D intake be adequate during this period. It has become evident that the risk of osteoporosis later in life is influenced by maintaining sufficient calcium intake from childhood and throughout life. Unfortunately, dietary intake often becomes erratic during this period just when demand is higher for iron, protein, and other nutrients. Therefore it is essential for the adolescent to maintain basic nutritional requirements.

With increasing body dimensions, there is an associated increase in blood volume and in the strength of cardiac contractions, although the pulse rate diminishes. Both cardiovascular and pulmonary functions reach adult values during adolescence, but usually they do not keep pace with musculoskeletal growth, leading to decreased exercise tolerance and marked fatigue at times in active teens. The basal metabolic rate gradually declines to adult levels during this period.

Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome

Recent research has shown that the ability to burn fat during exercise declines after puberty. This metabolic change along with changes in activity and diet can lead to obesity during adolescence. Not only is obesity a significant factor in the teen’s self-image, it also constitutes a major threat to their health and leads to pathophysiologic changes in metabolism that predispose the teen to diabetes and cardiovascular disease as well as permanent joint damage.

Overweight refers to and excess amount of body weight that may be a result of muscles, bone, fat, and water.

Obesity refers to an excess amount of body fat. Overweight and obesity are due to a caloric imbalance. This imbalance may be due to more calories consumed than expended, and can also be affected by various genetic, behavioral, and environmental factors.

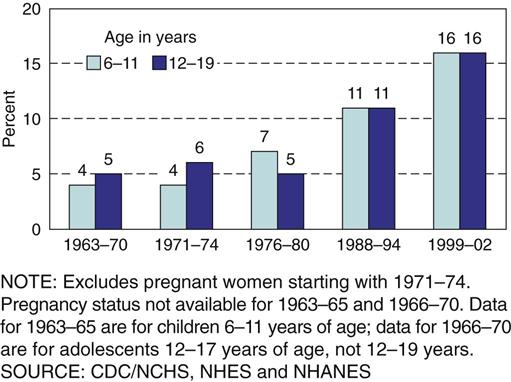

Obesity is determined by calculating the body mass index (BMI). The BMI is an international standard and is calculated based on the child or adolescent’s age as well as height and weight. Standard charts are provided within the back covers of this text. Adolescents are considered clinically obese if the BMI is at the 95th percentile or greater for their age. Adolescents whose BMI is between the 85th percentile and the 94th percentile are clinically “at risk for obesity.” Note that the amount of fat normally differs with gender and age until after age 20, thus adult BMI charts are not applicable to adolescents. Figure 23-1 illustrates the prevalence of adolescent obesity in the United States over several decades.

Alarm has been expressed regarding the recent increase in obesity in children and teens. In the 6- to 11-year age group, the number of obese children has doubled between 1980 and 2000, whereas the number in the 12- to 19-year group has tripled. Obesity in children 6 to 11 years (in the United States) has risen from 7% in 1980 to 18% in 2010. Obesity in the 12-19 age group has risen from 5% in 1980 to 18% in 2010. Accompanying this significant trend is a marked increase in children and young adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus, elevated blood cholesterol/lipid levels, and increased blood pressure. The prevalence of psychological problems is also higher in obese children. Because many obese children continue to be obese adults, these conditions will lead to a higher incidence of cardiac problems, strokes, and musculoskeletal problems such as osteoarthritis. The increased obesity in children and young adults appears related to increased intake of high fat and high carbohydrate snacks, high sugar soft drinks, and “fast foods” in conjunction with decreased exercise and activity related to excessive time spent watching television or playing computer games. It is recommended that nutritious, healthy snacks and meals as well as increased regular physical activity be encouraged. This will also promote general health, growth, and development of the body. A child’s body mass index (BMI) calculated from the height and weight should be monitored if unusual weight gain is noticed.

Metabolic syndrome is defined in various ways, but three factors are common to all definitions: presence of significant abdominal fat mass resulting in an increased waistline measurement, changes in glucose metabolism and changes in lipoprotein metabolism. Changes in cardiac output, hypertension and/or type 2 diabetes may also be present. (See Chapter 12 for discussion of coronary artery disease and Chapter 16 for discussion of diabetes.) Metabolic syndrome occurs in 1% to 4% of children and adolescents and in 49% of significantly and clinically obese young people. Obesity is the primary cause of the syndrome and any weight loss is significant in preventing complications.

The underlying cause of metabolic syndrome is the release of insulin antagonists by adipose tissue. An increased proportion of body fat results in insulin resistance and changes in metabolism. Specific changes resulting from insulin resistance are discussed in Chapter 16. These changes are a major risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. The incidence of cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension and congestive heart failure is higher in individuals with metabolic syndrome and onset is as early as the teens in adolescents with the syndrome. The same is true of type 2 diabetes. Earlier onset of cardiovascular disease and/or type 2 diabetes leads to earlier complications and significantly shortened life expectancy. The current generation of adolescents may be the first to have a shorter life expectancy than their parents.

Musculoskeletal Abnormalities

During the growth spurt, muscular development lags behind skeletal growth; thus, less support is available for the weight-bearing areas. Coordination may be impaired at times. Adequate warm-up before exercise or competitive sports is essential to reduce the risk of injury. Postural abnormalities can easily develop during this growth period. Other factors, such as developmental abnormalities in children with Down syndrome or cerebral palsy, may be further aggravated during this period (see Chapter 14). If a correction of a postural abnormality is not undertaken in the early stage, the curvature will progress throughout the adult years, leading to complications.

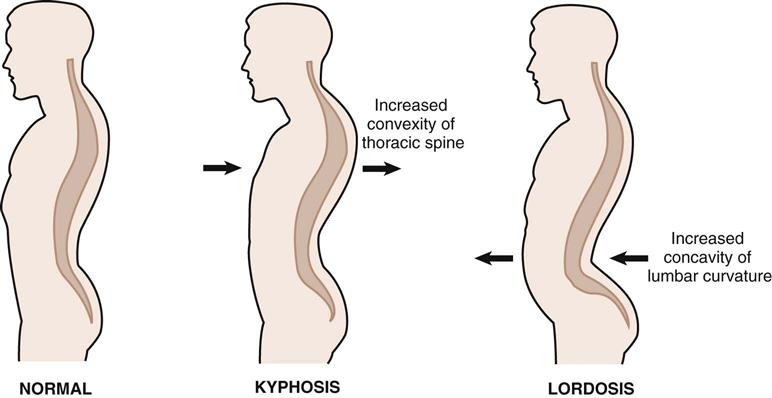

Kyphosis and Lordosis

Kyphosis, often called hunchback or humpback, is an increase in the convexity of the thoracic spine (Fig. 23-2). Although it often develops in mature adults secondary to disorders such as osteoporosis (bone demineralization) and tuberculosis, a milder and reversible form, commonly of postural origin, occurs during the adolescent growth spurt. Teens frequently hunch over, particularly if they are taller than their peers or are self-conscious about breast development. Also, skeletal muscle support may be temporarily inadequate. Marked kyphosis can interfere with lung expansion and ventilation. Exercise and postural change can usually reverse mild deformities, although severe deformity may require surgery or a brace for correction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree