98

CHAPTER OUTLINE

■ EPIDEMIC OF PRESCRIPTION OPIOID ABUSE

■ TREATING PAIN IN THE PRESENCE OF ADDICTION

■ TREATING ADDICTION IN THE PRESENCE OF PAIN

INTRODUCTION

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, experts bemoaned clinicians’ inability “to distinguish between pain patients and addiction patients.” If only it were so simple. Unfortunately, the conditions are far from mutually exclusive, as those who work in either field are well aware, and in fact, each increases vulnerability to the other, impedes treatment of the other, and obscures the diagnosis of the other.

A chapter on pain may seem an inappropriate place in which to define addiction in a text devoted to the subject, yet it is precisely in those patients who have chronic pain under treatment with opioids that the diagnostic criteria have been most contended. Both the American Psychiatric Association and the World Health Organization elected to avoid the term “addiction,” which is pejorative, in favor of “dependence,” which is ambiguous. This word is used to indicate that state which most understand as addiction, yet is easily confused with the term “physical dependence,” which is normal and essentially universal in patients taking daily opioids, benzodiazepines, and many other drugs. In the service of clarity, this chapter will use the term “substance use disorders” (SUDs) to include the psychiatric disorders “addiction” and “abuse” and will avoid “dependence.”

Addiction is understood to consist of a change in brain function that leads to inordinate valuing of substance use, relative devaluation of other things, and diminished ability to control impulses related to substance use and acquisition (1–3). Since these are not fully observable clinically, the condition is recognized by its epiphenomena, the “three Cs”: impaired ability to Control use of the substance, Compulsive use (or Craving), and continued use despite adverse Consequences (4). Those who suffer from this condition are understood to have contracted it not because they wished it but despite their efforts to avoid it. Thus, they are victims of the illness, not perpetrators, and the term addiction is not used disparagingly.

SIGNIFICANCE

A growing percentage of the patients seeking treatment for substance use disorders are addicted to prescription opioids (5,6), and many suffer from comorbid chronic noncancer pain (CNCP). Rosenblum et al., for example, surveyed 390 patients from methadone (addiction) treatment programs and 531 from short-term inpatient substance use treatment programs in New York State. They found that 37% of the methadone patients reported severe chronic pain, as did 24% of the inpatients (7). Many attributed their addiction, correctly or not, to exposure to opioids taken for pain. Patients with other addictions also appear to have a relatively high prevalence of pain; in a population of predominantly alcoholic patients in outpatient substance abuse treatment, 29% reported severe chronic pain (8).

Estimates of the prevalence of SUDs in those with CNCP vary widely, in large part due to variable methodology, inadequate investigation, and inappropriate definitions of addiction. For example, in 1992, Fishbain et al. reviewed 24 studies and found that only 7 used acceptable diagnostic criteria. The studies suggested that 3.2% to 19% of CNCP patients had comorbid substance use disorders (9). In a subsequent structured review of 67 studies, Fishbain et al. investigated the risk that patients exposed to therapeutic opioids would develop an SUD or aberrant drug-related behaviors (10). Of those with no prior SUD, only 0.19% developed an SUD and only 0.59% had aberrant behaviors. A review by Minozzi et al. confirmed the low likelihood that pain treatment will result in opioid addiction. They found incidences in studies ranging from 0% to 24%, with a median of 0.5% (11). In contrast, Passik et al. (12) found that one-third of 109 patients entering treatment for prescription opioid addiction had initiated opioid use through a legitimate prescription. Boscarino (13), on the other hand, found that 35% of patients receiving chronic opioid therapy (COT) for pain had an opioid use disorder.

If we assume that these findings accurately reflect reality, they suggest that opioid analgesia rarely leads to SUDs (at least in short-term use); however, those with SUDs are highly represented in the population receiving opioids. This idea is supported by findings of Weisner et al. (14), who studied four million customers of two large Pacific Northwest insurance companies. They found that customers with identified SUDs were more likely to receive Schedule II opioid prescriptions, received opioids in higher doses, for longer periods of time, and were more likely to receive concomitant sedative–hypnotics than those without SUDs.

Supporting this conclusion, in a national sample of 1,408 patients entering a nonpublicly funded treatment for opioid dependence, Cicero et al. found that over 80% had been exposed via a prescription, which they then misused. However, most had had a prior substance use disorder during their early or late teens, and they had had a mean of three prior treatments for substance use (15). Approximately 86% indicated that pain played a role in their initial opioid use.

Taken together, these studies suggest that US physicians are not so much creating addiction as inadvertently (one hopes) prescribing opioids (and sedatives) to persons with preexisting substance use disorders. The studies are, however, hard to reconcile with two events: There was clearly an “epidemic” of abuse/addiction related to OxyContin in Appalachia that was fueled largely by intemperate prescribing for pain, and there has been an “epidemic” of prescription opioid use throughout the country as prescribing has increased. One interpretation that is consistent with these data would be that the abuse/addiction results largely from diversion of legitimate prescriptions.

EPIDEMIC OF PRESCRIPTION OPIOID ABUSE

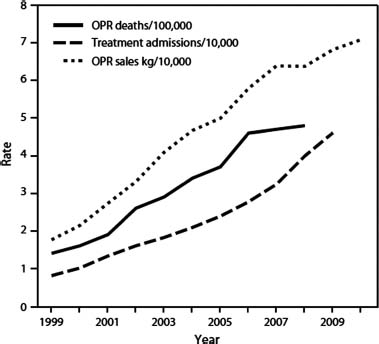

Law enforcement agencies, federal and state governments, and clinicians have become concerned about a dramatic increase in prescription opioid-related drug misuse, addiction, and deaths. Since this has occurred in the context of an equally dramatic rise in the prescription of opioids for chronic pain, prescribing practices have been blamed for the “epidemic” (Fig. 16) (98-1). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data confirm that the rise in therapeutic opioid sales is paralleled by a rise in admissions for addiction as well as a rise in overdose deaths. Furthermore, the states with highest sales seem to have the highest opioid-related death rate.

FIGURE 98-1 Increased opioid availability paralleled by increased opioid-related deaths and admissions for addiction treatment. (From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers—United States, 1999—2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011;60:1487–1492.)

Data clearly show that most nonmedical use of opioid analgesics is not carried out by a person who received a prescription from a doctor; rather, it occurs in people who received it free from a friend or relative or who obtained it from an illicit drug dealer or from fraudulent multisourcing via multiple providers (17,18). It appears therefore that two phenomena intersect to create the current epidemic of opioid misuse and associated harm. First, greater quantities of opioids available for therapeutic use mean greater quantities available for diversion and misuse. Second, persons with risk of misuse are more likely to be prescribed opioids. A multidimensional approach to pain management may reduce the need for opioids, and improved prescribing practices have the potential to reduce prescribing to poor candidates for COT.

PROBLEMS OF COMORBIDITY

Reciprocal Vulnerability

Data reviewed above suggest that persons with addiction are susceptible to chronic pain. This is not unexpected, given that addiction increases the risk of trauma and of such painful illnesses as pancreatitis, cirrhosis, strokes, HIV infection, and peripheral arterial disease.

While the converse situation, in which pain increases vulnerability to addiction, seems likely, the data demonstrate that this may be less common than often thought. In fact, as far back as 1993, Polatin et al. (19) showed that when chronic low back pain and substance abuse coexisted, the substance abuse had preceded the pain in 94% of cases. Similarly, Potter et al. (20) found that of 48 patients hospitalized for controlled-release (CR) oxycodone addiction, 77% had a nonopioid substance use problem prior to taking oxycodone CR. In a highly selected group of patients undergoing pain rehabilitation, our group found that 33% of addiction began with medical exposure, 64% was with recreational use, and 3% was undetermined (21). Needless to say, the proportion of patients in a pain clinic who became addicted medically would be much higher than the proportion in the community.

What is clear, however, is that disabling chronic pain and addiction share several risk factors, including childhood trauma/neglect, adult trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder (22).

Diagnostic Confounds

Addiction may complicate the diagnosis of pain, since it provides an incentive, which may or may not be consciously appreciated by the patient, to maximize complaints and minimize reports of benefit from nonopioid therapies. Given that most CNCP is due less to peripheral nociception than to central sensitization, the clinician is placed into a situation in which the primary, and sometimes only, diagnostic finding is patient report, which may be unreliable. Thus, the risk of undertreating actual pain coexists with the risk of inappropriately supporting addiction (not that these are mutually exclusive), and there are few objective guides as to optimal choices.

Pain also complicates the diagnosis of addiction. The person who has developed an addiction to prescribed medications may not demonstrate the typical diagnostic clues seen in the “recreational” drug abuser. He or she is less likely to have engaged in illegal activities to support drug use or to have impoverished the family to obtain drugs, since they are usually funded by insurance. He is less likely to have unpleasant encounters with drug dealers in bad neighborhoods, since the medications are obtained from a pharmacy. The quality and sterility of prescription pharmaceuticals make infectious complications unlikely, and, of course, many of the adverse consequences of opioid use can be ascribed to pain.

Pain probably makes it harder even for the patient himself to recognize that an addiction has developed. Unlike the person who began using substances recreationally, that is, in pursuit of good feelings, and gradually transitioned into using in order to prevent distress, the person with pain initiated use to stop feeling bad—so the transition to addictive use may be less apparent. Thus, many factors confirm to the pain patient that he or she is “not like those people” with addiction.

Treatment Impediments

Treating CNCP is more difficult in the presence of addiction. Patients with opioid addiction may not respond as readily to nonopioid pain treatments such as other medications, injections, physical therapy, or cognitive– behavioral interventions as nonaddicted patients. Opioid therapy is often impeded by difficulty establishing the correct dose, since upward titration may continue indefinitely. This can lead to the situation in which patients arrive at pain clinics taking massive doses of opioids, yet whose pain remains extreme and whose function is virtually nil.

The therapeutic relationship is challenged by the presence of addiction. The patient may believe that he or she is entitled to relief of pain, even if this is not achievable, while the prescriber may suspect that the pain complaints reflect drug seeking. An impasse may develop, with escalating mutual mistrust and hostility.

Similarly, treatment of addiction is complicated by chronic pain. The pain patient may fail to identify with other addicted people who lack “legitimate” reasons for use and who report addiction-related behaviors that are uncommon in those addicted to therapeutic opioids.

Diagnosis of Addiction in CNCP

The criteria for a diagnosis of addiction in the patient with CNCP are similar to those in patients without pain; however, they may be more difficult to discern.

The DSM-IV (23), which establishes the previous standard criteria for psychiatric diagnosis, at times hindered the correct diagnosis of addiction, primarily because of an overemphasis on tolerance and physical dependence. These are normal and to be expected in patients taking daily prescribed opioids or sedatives. In fact, withdrawal can be elicited in normal subjects following a single dose of morphine (24), which confirms the lack of diagnostic value of this criterion. This misunderstanding has been corrected with the publication of DSM-5. The new term “opioid use disorder” requires a maladaptive pattern of use leading to significant impairment or distress, as manifested by at least two of the following, occurring within a 12-month period (abbreviated) (25):

1. The opioid is often taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than intended.

2. There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control use.

3. A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain, use, or recover from opioid effects.

4. Recurrent use results in failure to fulfill major role obligations.

5. There is continued use despite persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the substance.

6. Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are reduced because of use.

7. There is recurrent use in situations in which it is physically hazardous.

8. Use is continued despite knowledge of persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problems likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the opioid.

9. Tolerance (not counted for those taking medications under medical supervision).

10. Withdrawal (not counted for those taking medications under medical supervision).

11. Craving or a strong desire or urge to use the opioid.

The indicators of therapeutic opioid addiction are often more subtle than in the case of recreational addiction. Loss of control tends to be manifested by an inability to ration—despite knowing that he or she has enough medication to last only 10 days, the patient exhausts the supply in 3 days, thus running out early, possibly necessitating a trip to the emergency department. Craving may be demonstrated by reluctance to meaningfully discuss any treatment other than opioids, as physical therapy, meditative therapies, steroid injections, etc. hold little interest to the person who is preoccupied with opioids. Use despite adverse consequences is less likely to be shown by legal entanglements (patients who have a prescription are less likely to steal medications and those who do not drive due to pain do not receive citations for driving under the influence) than by family reports that the person loses the thread of a conversation, falls asleep at the dinner table, or takes medications to go on a family excursion only to fall asleep. Multisourcing is a common occurrence in the person who has developed an addiction to prescription opioids, and it is often identified only by reviewing the state electronic prescription drug monitoring program’s records. Families may be much less clear in confirming that their loved one has a therapeutic addiction than they would be in the case of cocaine or alcohol, and may see the adverse consequences of opioids as simply the price that must be paid for some measure of pain relief.

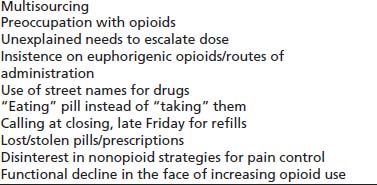

RED FLAGS FOR ADDICTION

The clinician should be concerned that addiction is present or developing when certain behaviors are noticed (Table 98-1).

TABLE 98-1 RED FLAGS FOR ADDICTION

Pseudoaddiction

Pseudoaddiction is a term that has been used to describe behaviors that mimic addictive behavior, but which result not from addiction but from inadequate analgesia (26). These may include what seems to be inordinate drug seeking, doctor shopping, using others’ medications, and running out of medications early. The behaviors improve when pain is controlled. The concept, based on a case report, is elegant and simple. In practice, however, both under-medicated patients who are not addicted and appropriately medicated patients who are addicted may be drug seeking, and both cease drug seeking, at least transiently, when their needs are met. So the distinction is often made with difficulty and in retrospect, that is, when the patient’s behavior normalizes for an extended period after adequate pain control is provided (27).

Screening

The overlapping tasks of identifying SUDs in those with CNCP and of predicting those at high risk for developing opioid use problems in therapeutic use have received considerable attention. The tasks overlap since the best predictor of future substance use problems is previous substance use problems.

At a minimum, all patients receiving long-term opioids should be asked whether they have ever felt that the use of prescribed pain medications had become a problem in their life and whether any of their loved ones had shared these concerns.

Similar questions, regarding nonopioid substance abuse, may help to identify those most at risk for developing aberrant behavior if prescribed opioids. In a large (n >8M) claims database, Rice et al. (28) reviewed >800,000 cases who had received an opioid prescription between 2007 and 2009 and determined which had been diagnosed with opioid abuse during the period from 1999 to 2009. Those diagnosed with nonopioid drug abuse had almost 10 times the likelihood (OR = 9.89) of being diagnosed with opioid abuse.

Unfortunately, simple questioning may fail to reveal substance use disorders, as patients often give inaccurate reports (29). In a study of 109 chronic noncancer pain patients, Berndt et al. (30) found that 21% concealed drug use, 2% were not taking prescribed medications, and 9% were uninterpretable.

Screening Tools

A number of instruments have been created to screen for the presence of SUDs in those with CNCP as well as to predict the likelihood of aberrant behaviors should opioids be prescribed. The simple, four-item CAGE inventory (31) has been modified for use in detecting drug abuse (32) (available at http://www.partnersagainstpain.com/printouts/A7012DA4.pdf).

The Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire (PDUQ) is a more comprehensive (42 item) instrument shown to identify SUDs in CNCP patients (33) (available at http://www.opioidrisk.com/node/519). It has been modified (PDUQp, 31 items) for self-administration (34) (available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2630195/).

The 28-item Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST), though not developed for patients taking prescribed drugs, may identify patients with recreational or prescribed SUDs (35) (available at http://www.drtepp.com/pdf/substance_abuse.pdf).

Prediction

Instruments designed to predict aberrant drug-related behavior are conceptually distinct from those designed to detect existing SUDs; however, they often have similar item content. Many seem to “predict” the past, in that they detect preexisting addictive disorder, which predicts future aberrant behavior. Nevertheless, these instruments help to identify patients likely to encounter difficulty with adherence to an opioid treatment plan.

Webster and Webster developed the Opioid Risk Tool (ORT), which initially showed success at categorizing patients into low (≤3), moderate (4–7), or high (≥8) risk for aberrant drug-related behaviors (36) (available at http://www.partnersagainstpain.com/printouts/Opioid_Risk_ Tool.pdf). Subsequently, it performed less well than comparator instruments, perhaps because of comprehension difficulties. A comparison of the results of the test when self-administered showed significant differences from results when it was clinician administered, with the latter indicating higher risk (37). Even if clinicians do not formally administer the ORT in their practices, it is useful to know the traits captured by the test and to increase vigilance and precautions to patients when they are present.

The Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPP) was developed by Butler et al. (38) and has been revised. The SOAPP-R (39) administered prior to opioid therapy was shown to be a reliable and valid predictor of aberrant behavior after 5 months of therapy (available at http://www.venturafamilymed.org/Documents/SOAPP-R.pdf). A 14-item version has also been produced. Several versions of the SOAPP and supporting documents are available (40).

Unlike self-report instruments, the DIRE (Diagnosis, Intractability, Risk, Efficacy) is completed by clinicians to aid in predicting the risks of chronic opioid treatment (41) (available at http://www.opioidrisk.com/node/1202). A comparison of the SOAPP, ORT, and DIRE suggested that all are useful, especially when supplemented by clinical interview (42).

The Current Opioid Misuse Measure differs somewhat from instruments designed either to diagnose substance use disorders or to predict abuse-related difficulties during opioid therapy, as it is intended for use in the ongoing monitoring of patients on COT to help identify those with aberrant opioid-related behaviors. It is a 17-item self-administered questionnaire that has demonstrated good reliability in pain clinic patients (43) as well as in the primary care setting (44) (available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2955853/table/T1/).

Iatrogenic Addiction in CNCP

Although opioids are recognized as one of the most important components of treatment for some patients with CNCP, there is reluctance on the part of some prescribers to provide them. In part, this is because the benefits of COT are modest or equivocal (45) and the time required to prescribe it responsibly is considerable. However, the greatest concern of prescribers is probably the fear of causing the disease of addiction to develop. Indeed, physicians have been successfully sued for “addicting” their patients, and a pharmaceutical company was fined over $630 million for having minimized the addictive risks of its product.

Studies cited above (9,10,19,20) suggest that a large preponderance of people who have become addicted to therapeutic opioids did not become so because of the prescribing practices of physicians, at least not directly. And government studies of sources of nonmedical opioids similarly show that less than 1/5 of abusers received a legitimate prescription from a physician. It is therefore likely that the wide publicity received by physicians and pharmaceutical company sanctions has created the false impression that addiction in the course of pain therapy is rampant. In fact, the evidence suggests that it is uncommon.

Some animal studies suggest that the presence of pain diminishes the rewarding effect of opioids (46,47). Others find that not only opioids but other analgesics, such as anti-inflammatories, are reinforcing in the presence of pain (see summary by Zacny et al. (48)). Humans can easily distinguish the negative reinforcement that occurs when ibuprofen relieves a headache from the positive reinforcement that occurs when an opioid is taken recreationally. The distinction may be more difficult to discern in animal models.

It is, however, clear that many patients who have become addicted while using opioids for analgesia report that they did so without ever having become “high.” Nevertheless, the development of addiction is a serious and life-threatening occurrence, though the magnitude of risk for this is unknown. Clinical experience has supported the conclusions of some very old, small, and poor-quality studies (49,50) to the effect that the risk of inducing addiction with brief (<3 months) treatment is quite small, perhaps 3 per 1,000. Experience with recreational drug and alcohol use shows that addiction, in nearly all cases, has an “incubation period.” Our understanding of addiction as a consequence of neuroplasticity in the brain suggests that its occurrence should be contingent on a prolonged period of frequent or continuous exposure; that is, the risk of addiction could be proportional to dose and duration of therapy, as well as such known factors as pharmacokinetics and other factors that predispose to addiction. If true, it may be some time before we know the true risks of long-term opioid treatment.

We do know that triggering relapse is far easier than the induction of addiction and the fact that so many people addicted to prescription medications had prior nonmedical SUDs suggests that this may be the occurrence that largely informs our perceived “epidemic of addiction.” Animal (51) and human (52) studies demonstrate that one of the most effective ways to elicit resumption of dormant drug seeking is exposure to the prior drug of choice or a similarly reward-producing drug. A case came to our attention of a man who for over a year was successfully recovering from a heroin addiction, until he was exposed to intravenous (IV) midazolam along with an opioid for procedural sedation. He experienced immediate drug craving, obtained and injected heroin, to which he was no longer tolerant, and died the day of the procedure. We lack studies to clarify the risk of relapse if, for example, a person recovering from alcohol dependence is exposed to COT, rather than his drug of choice. In a study of 20 patients treated with chronic opioids, 9 of whom were thought to misuse their prescription analgesics, those with a history of alcohol abuse alone were less likely to abuse analgesics than those with other prior substance use disorders (53). However, such people are nevertheless likely to be at elevated risk, as suggested by the findings of Compton et al. (54) that in a representative sample of US adults (N = 43,093), those with alcohol dependence had more than 18 times the odds of having drug dependence.

The combined evidence suggests that the most important precautions for prescribers to take when prescribing opioids are to (a) identify those at most risk for developing opioid use disorder, which will be primarily the young and those with a prior SUD or a co-occurring mental health disorder, and (b) institute practices that minimize the likelihood of diversion.

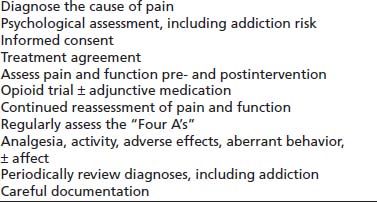

Universal Precautions in COT

Gourlay and Heit (55) proposed an approach similar to that used for infectious disease in which universal precautions are used with all patients, without regard to their risk factors for a contagious condition. The approach was intended to be useful for all patients in chronic pain; however, it is most relevant for those being considered/initiated in a trial of COT and is proposed as a way to make this therapy accessible to patients while helping protect them from the consequences of an addictive disorder (Table 98-2).

TABLE 98-2 THE TEN STEPS OF UNIVERSAL PRECAUTIONS IN PAIN MEDICINE

Data from Gourlay DL, Heit HA, Almahrezi A. Universal precautions in pain medicine: a rational approach to the treatment of chronic pain. Pain Med 2005;6(2):107–112.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree