38

CHAPTER OUTLINE

Heavy drinking and significant alcohol-related problems are commonly reported by college students nationwide (1). Peak lifetime alcohol use generally occurs in an individual’s late teens and early twenties. The prevalence of heavy episodic (or binge) drinking, defined by the National Institutes on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) as reaching a blood alcohol level of 0.08 or higher (usually by consuming five or more drinks for men, four or more for women, over a 2-hour period) (1) and the detrimental consequences resulting from this type of drinking have led the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Surgeon General to classify college student binge drinking as a major public health problem. Though extensive research and administrative efforts have been aimed at decreasing college student binge drinking, rather than decreasing binge drinking, driving under the influence and unintentional student deaths related to alcohol are on the rise (2). What follows is a review of the research on college student drinking including prevalence rates and consequences, risk factors for college drinking, and a discussion of empirically supported interventions and treatment practices.

Drinking Rates and Disorders among College Students

Reports indicate approximately four out of five (81%) of college students have consumed alcohol, and 68% have been drunk at least once in their lives (3). When examining only the past month, 40% reported having been drunk, and 4% reported drinking daily, while 36% have engaged in heavy episodic drinking (five or more drinks in a row) in the past 2 weeks (3). These rates are comparable to non– college students, with the exception that college students are more likely to engage in heavy episodic drinking. While estimated prevalence of alcohol abuse and dependence varies across studies, estimates indicate approximately 18% to 21% of college students meet criteria for an alcohol use disorder (8% to 13% abuse, 7% to 13% dependence) (4,5). Furthermore, of students diagnosed with alcohol abuse or dependence during early college, an estimated 43% continue to meet criteria (i.e., are not in remission) after college (6).

Alcohol-related Problems and Consequences

An estimated 1,825 unintentional college student deaths per year involve alcohol (2). College-specific, drinking-related consequences range from the extreme (death, injury, assault, sexual abuse, unsafe sex, health problems and suicide, drunk driving) to the less problematic (academic problems, vandalism, property damage, police involvement). The NIAAA Task Force on College Drinking categorized college student drinking consequences as damage to self, others, or the institution (as well as the overlapping categories of drinking and driving, high-risk sexual behavior, and physical and sexual aggression) (7).

Damage to Self

Nausea, vomiting, and hangovers are among the most common negative effects produced by alcohol (7). Higher levels of drinking are associated with poorer academic performance, as indicated by grade point average (8). College students put themselves at risk for arrest by driving under the influence (29%) of (2) and/or are frequently involved with local or campus police because of drinking (5%) (9).

Damage to Others

In addition to direct harm to self, there are numerous secondary effects, or damage to others, from alcohol use. These include being impacted by motor vehicle accidents, vandalism, litter, noise, fighting, public urination, vomiting, and problematic encounters with drunken individuals. For example, among students who live on campus and drink either lightly or not at all, 60% experienced interrupted study or sleep due to other students’ drinking, 48% took care of a drunk student, and almost 20% had a serious argument or experienced an unwanted sexual overture (for females) where alcohol was involved (9). It is estimated that approximately half a million college students annually are unintentionally injured because of drinking; 646,000 experience assault by another drunken student, and 97,000 experience alcohol-related sexual assault or date rape (2).

Damage to Institution

College administrators, staff, and campus police often have to deal with the consequences of students’ alcohol use. Resulting problems, such as violence, vandalism, and property damage, are relatively common. More than one-fourth of colleges with low rates of drinking, and more than half of those with high rates of drinking, report moderate to major problems with alcohol-related vandalism and property damage (10). Approximately 11% of students have damaged property while under the influence (9). Further, sporadic binge drinkers and frequent binge drinkers were 4 and 10 times more likely, respectively, to report having damaged property than were nonbingers (11), and it is estimated that 50% to 80% of violence occurring on campuses is alcohol related (12).

Risk Factors for College Student Drinking

Risk factors for alcohol dependence more broadly include a focus on the influence of parental drinking through modeling and genetic predisposition to problematic alcohol use. While these factors are at play across developmental stages, college student drinking, while varied, is predominantly considered a developmentally limited pattern of use characterized by high rates of alcohol use that does not typically persist past students’ transition to postcollege roles. Identified risk factors for heavy drinking among college students include demographic and environmental influences, cognitive and motivational factors (e.g., perceptions of the normative nature of drinking, expectations of positive outcomes from drinking), and affective factors (mood or anxiety problems, a desire to avoid negative emotions or enhance positive ones) among others (13).

Demographics

Sex and Ethnicity

On average, college men drink more often, consume larger quantities of alcohol, and are more likely to engage in binge drinking than are college women (3,14). College men are also more likely to meet criteria for an alcohol use disorder and experience more alcohol-related problems (15–17). However, it has been hypothesized that current measures of alcohol-related problems assess primarily externalizing behavior problems and do not assess internalizing problems (e.g., drinking related to the management of anxiety and depression), which may be more prevalent in females, suggesting that current estimates may be underrepresenting negative consequences of alcohol use for women (18).

With regard to ethnicity, research on both the national and local level has found that White college students are the most likely to engage in heavy episodic drinking and, like Native American/Alaskan Native students, tend to experience more problems related to drinking (10,19). In contrast, African American students are least likely to engage in heavy drinking and are less likely to experience alcohol-related problems, followed by Asian American students (19). Based on a review of national studies of adolescents and young adults, O’Malley and Johnston estimated that 40% to 50% of White students engage in binge drinking, in comparison to 30% to 40% of Hispanic/Latino and 10% to 20% of African American students (19). Compared to Hispanic/Latino and White gender differences, African American female college students drink proportionally less than do African American male students.

Athletics

For both males and females, involvement in athletics at the high school or college level is associated with more frequent drinking, including binge drinking and other risk behaviors (20–22). Drinking rates vary notably from in-season to off-season, resulting in use and/or consequences being significantly reduced during the competitive season only to increase when the season ends (23–26). Students in team sports tend to report higher drinking and binge drinking rates than students in individual sports (27), with drinking rates varying across teams (21,28). Expectancies, particularly positive outcome expectancies, are associated with heavier drinking by student athletes (29–32). Team captains and leaders are particularly vulnerable to these behaviors, as increasing level of participation from nonparticipation to team captain is positively associated with binge drinking (20). But, one need not be a team member to be at high risk—across 140 colleges, students (team and non–team members) who rated athletics as important have higher rates of heavy drinking (9).

Membership in the Fraternity/Sorority (Greek) System

Fraternity and sorority organizations are environments in which heavy drinking is considered normative and is considered a sexuality, friendship, and socialization enhancer (33,34). Members of the Greek system consume alcohol at greater frequencies and quantities than their non-Greek peers (10,35,36). Caudill et al. (35) surveyed more than 3,400 members of a single national fraternity across 32 states and found 97% drank alcohol, 86% were heavy episodic drinkers, and 64% were frequent heavy episodic drinkers (5 or more drinks per occasion on three or more occasions in the past 2 weeks). Greek membership has consistently been shown to be a risk factor for heavy episodic drinking, especially among males (10,34,35,37), and both selection (heavier drinking students choose to join the Greek system) and socialization have been found to influence drinking by fraternity and sorority members (34,36,37). However, there can be a great deal of variability in drinking rates within a fraternity or sorority, and not all Greek organization members drink heavily or at all (34).

The Post-9/11 Veterans Educational Assistance Act of 2008 (the 9/11 GI Bill) provides over 2 million veterans who served in either Afghanistan (Operation Enduring Freedom, OEF) or Iraq (Operation Iraqi Freedom, OIF) with the opportunity to attend college full time (38). While the 9/11 GI Bill gives OEF/OIF veterans access to educational benefits, many veterans will return from deployment with physical and psychological challenges that may impede their academic success (39). In particular, research suggests OEF/OIF veterans have high rates of alcohol use and psychiatric disorders that could potentially interfere with class attendance, decrease grades and tests scores, and/or lead to withdrawal/dropout from college. Further, the transition from the battlefield to the classroom can be filled with unique stressors that veterans may not be prepared to handle. Despite the potentially negative effects of alcohol use and psychiatric symptoms on academic success among OEF/OIF veterans, relatively little research have actually examined this relationship. A recent pilot study at a 4-year state university found 73% of veteran college students experienced a difficult transition from military to college life, 62% felt academically unprepared for college, 21.4% reported a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and 14.3% reported a diagnosis of depression (40,41). Additional research has shown that veteran college students’ past year alcohol use was higher than students in general (87.3% vs. 82.5%, respectively), and veteran students engage in heavy episodic drinking at a rate similar to other students (39.1% vs. 36.8%, respectively) (42). Collectively, these data suggest returning veteran students are at risk for psychiatric symptoms and heavy alcohol consumption both of which could interfere with veterans’ academic success.

Individual and Environmental Risk Factors

Drinking Expectancies and Motives

Alcohol expectancies are the set of beliefs one carries about the positive and negative effects of alcohol consumption and have been shown to predict both current and future alcohol use (43–48). Drinking expectancies begin to form as early as the third grade (43). Positive expectancies, or the anticipated valued effects of alcohol consumption, are stronger predictors of drinking than are negative expectancies (44) and have been shown to predict drinking (45) and to differentiate between problem and nonproblem college student drinking (44). Furthermore, positive expectancies have been found to explain a large degree of variance in the relationship between early experiences with alcohol (e.g., parental, peer, and media modeling) and subsequent problem drinking in adolescence (43) and in college (49) and are associated with higher rates of lifetime alcohol use (50). Expectancies measured with both explicit and implicit measures predict alcohol consumption (51). Recent evidence indicates that implicit measures predict additional unique variance over explicit measures of alcohol expectancies in drinking behaviors (52). Furthermore, expectancies can be primed out of conscious awareness (52), indicating that expectancies influence alcohol use and can operate outside of awareness. Although expectancies are associated with both the onset and maintenance of alcohol use, studies evaluating interventions that challenge expectancies have demonstrated some efficacy, but results have been mixed, and therapeutic effects, when present, are not maintained after a short period (i.e., 4 weeks) of time (53).

Expectancies, beliefs about the effects of alcohol whether or not someone drinks, likely develop into motives, or a person’s stated reason for drinking, over time. Drinking motives are based on anticipated positive or negative reinforcement and, not surprisingly, predict alcohol use behaviors (54–58). Conformity, enhancement, social, and coping reasons are the most cited drinking motives (54). Of these motives, social and enhancement motives, or anticipation of positive reinforcements (e.g., drinking to induce a positive mood), are most commonly endorsed by college students (56–58), followed by coping motives (e.g., coping with feelings of depression or anxiety) or negative reinforcements (59,60).

Different motives are associated with differing patterns of use. In a review of the drinking motive literature for individuals aged 10 to 25, Kuntsche et al. (56) noted that social motives are more typically associated with light, infrequent, nonproblematic use of alcohol and have been shown to be negatively related to heavy drinking and negative consequences in some studies. Alternatively, enhancement and coping motives are most strongly associated with heavy alcohol use and coping motives and are further associated with more alcohol-related problems. The well-documented relationship between coping motives (i.e., drinking to cope with depressed mood or anxiety) and problematic alcohol use is thought to represent a type of self-medication of emotional distress (61,62). Although the lack of an association between social motives and alcohol-related problems is a reasonably robust finding, recent evidence suggests that this association may differ by gender. LaBrie et al. (57) demonstrated that for female college students, social drinking motives not only predicted quantity of alcohol consumption but were directly associated with alcohol-related consequences, calling for more study of women’s unique reasons for alcohol use and consequences.

Beyond a direct relationship to alcohol use behaviors, drinking motives have been found to mediate the relationship between a range of genetic, environmental, and individual difference factors and alcohol use and likely shift with developmental stage (63–71). LaBrie et al. (72) examined the role of college adjustment and found that poor adjustment mediated the relationship between coping motives and drinking consequences, highlighting the importance of interventions to help students decrease stress and develop good coping skills. Drinking motives also appear to change with age and developmental stage. Littlefield et al. (73) prospectively assessed individuals over a 16-year period, beginning at the first year of college. They found that enhancement motives decreased from age 18 to 35, as did alcohol-related problems.

Social Norms and Misperceptions

Perceptions of what is “normal behavior” for a group of individuals, or social norms, are known to influence behavior. One of the major forms of human learning is facilitated by the process of modeling—whereby one individual or group, consciously or unconsciously, displays a behavior that others imitate. One consistent finding is that college students overestimate the rates at which other college students drink (34), the amount (74), and the extent to which other students support heavy drinking (18). The degree to which students overestimate other students’ drinking predicts their own increased consumption (75), and this overestimation was recently found to be the strongest predictor of college student drinking when controlling for a variety of other individual risk factors (76).

Environmental Risk and Protective Factors

Environmental factors can also impact alcohol consumption. Presley and colleagues noted that the cost of alcohol in and surrounding the campus environment is related to alcohol use and that increases in total cost can reduce consumption (14). This has significant implications for colleges surrounded by bars frequently offering drink specials or “happy hour” promotions in which the cost of a drink is dramatically reduced for a limited amount of time (which hastens the rate of consumption). The authors also note that when multiple drinking venues exist, long-term and short-term drinking problems also increase. Clapp and Shillington (77) found that, among other predictors, students who were in a setting where many people were intoxicated were almost 13 times more likely to report consumption of five or more drinks.

High-risk specific events, such as annual celebrations, are associated with increased consumption of alcohol. Events associated with high rates of drinking are generally well known (e.g., New Year’s eve, St. Patrick’s Day, spring break, Halloween, and high-profile sporting events) or may be personal events, including 21st birthdays, graduations, or major accomplishments (78). Consuming alcohol prior to departing for one’s intended social activity or eventual destination is referred to as “prepartying,” “pregaming,” “front loading,” “preloading,” or “prefunking” (79). Increased BACs and a higher incidence of consequences are associated with prepartying, particularly for women (80). One-third of students who violate their campus alcohol policy prepartied on the night the violation occurred (81). For those who preparty at least once per month, the type of alcohol consumed varies by gender (82) and, up to 50% of the time, involves the playing of “drinking games.” Drinking games can be as simple as having everyone drink when a word or phrase is uttered during a movie, can be time focused (e.g., one sip per minute), can be team sport focused such that losers of a game must drink (e.g., “beer pong”), or could be quite complicated with a range of rules surrounding gambling, card games, motor skills, or verbal skills (81). Drinking games have been identified as a risk factor for “problematic” drinking (13) and have been associated with heavy drinking episodes (77). In some places, the birthday tradition of downing one shot of hard liquor for every year of age increases risks for frank alcohol poisoning and/or aspiration of vomitus.

Involvement in athletics is associated with risk for higher rates of drinking and for consequences associated with alcohol consumption (13,83); and drinking-game participation can be associated with risky drinking for those involved in athletics (84,85). Yet, the culture surrounding collegiate sporting events seems to also influence and be influenced by alcohol with many students and alumni participating in “tailgating,” significant sporting events being associated with increased drinking, a high frequency of alcohol advertising aired during televised sports, and the general association of alcohol with celebration (78,83,86).

Environmental variables can also serve as protective factors against high-risk drinking. Many colleges have seen the emergence of designated substance-free housing options and 12-step recovery groups on campus. Although students may self-select into various living options (e.g., Greek systems, residence halls, and substance-free housing), it has been suggested that living in a designated substance-free housing environment, even for those who drink, is a protective factor for negative consequences including heavy episodic or binge drinking and is associated with increased use of preventive behaviors (including less drinking-game involvement and increasing use of a number of strategies for altering one’s approach to drinking) (87). Clapp and Shillington (77) found that the only protective variable associated with lower risk of heavy episodic drinking was whether the event in which drinking occurred was a date. In attempting to explain this finding, the authors speculate that students who are dating may be less likely to use alcohol as a “social lubricant” and suggest additional research is needed to further examine this apparent protective factor.

PREVENTION STRATEGIES AND INTERVENTIONS

College Drinking Prevention Strategies

Given the high prevalence of college student alcohol use and related harm, considerable research has focused on development of prevention and intervention approaches for this population. The NIAAA has taken a major leadership role in compiling, disseminating, and stimulating research to address the serious public health problem of college student drinking. The NIAAA’s influential 2002 report of the Task Force on College Drinking (88) represented the joint efforts of researchers and college presidents to address the harms of and solutions to college drinking. The Task Force report designated four tiers of prevention strategies. Tier I involves interventions with documented, replicated evidence of efficacy in college populations. Interventions listed within Tier 1 may be delivered in a one on one or group setting with a facilitator. Tier II involves interventions with documented evidence of efficacy in general populations that could be adapted for college students. Tier III involves interventions with logical and theoretical promise in need of more research, and Tier IV involves interventions with evidence of ineffectiveness. The Task Force report was accompanied by increased college drinking prevention research supported by NIAAA and was supported by other organizations including the Department of Education and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. In addition, several comprehensive reviews of the prevention literature have been conducted in support of, or subsequent to, the Task Force report (89–97), and in light of subsequent research, the Task Force report recommendations were updated in 2007 (1). Thus, over the past decade, there has been considerable progress and growing consensus in determining what works in college drinking prevention. The following sections briefly review evidence regarding the efficacy of both individually and environmentally focused interventions aimed at reducing college student drinking.

Individually Focused Interventions

As mentioned above, each of the interventions listed within Tier I as having documented empirical evidence of efficacy is an individually focused intervention. Specific campus intervention strategies (e.g., who delivers interventions, points of delivery, subpopulations targeted) vary across campuses typically depending on school size, staffing, and several other key variables. Research supporting their efficacy has studied the use of interventions with students mandated to treatment (i.e., sanctioned to complete a program after a policy violation), high-risk first-year students, students within the Greek system, individuals following a positive screen in either a health or a counseling center setting, as well as other groups of students on campus. Additionally, studies have examined peer versus professional delivery and have recently begun to examine the efficacy and benefits of Web-based delivery of interventions.

Multicomponent Skills-based Interventions

Multicomponent skills-based interventions (e.g., the Alcohol Skills Training Program: ATP) typically combine cognitive–behavioral skills training (such as identifying and planning for or avoiding risky situations; using protective behavioral strategies such as drink spacing, counting drinks, and limit setting to reduce intoxication during drinking events; discussing myths about alcohol’s effects; and communicating assertively about drinking decisions) with norms clarification (correcting misperceptions about drinking norms, exploring assumptions that everybody drinks), using a motivational interviewing (MI) (98) style to reduce resistance and promote change. Larimer and Cronce (90,91,96,97) reviewed 22 studies including a multicomponent skills intervention and found 13 of 22 produced statistically significant reductions in alcohol use, harmful consequences, or both. Methodologically, stronger studies (i.e., larger samples, longer follow-up, appropriate control groups) were the most likely to report statistically significant effects of the multicomponent skills approach.

Expectancy Challenge Interventions

A second cognitive–behavioral intervention designated as Tier I was expectancy challenge interventions (see “Drinking Expectancies” in preceding section). Expectancy challenge interventions are aimed at changing students’ positive expectations for alcohol intoxication and are delivered by two methods. The first method is experiential—the alcohol placebo effect is directly applied to demonstrate how one’s expectations about drinking influence his or her experience. Typically, students told they are drinking alcohol but actually receive a nonalcoholic drink (i.e., a placebo) still show the social or interpersonal effects associated with drinking for them (i.e., they become more social, talkative). Alternatively, students told they are not drinking alcohol when their beverage is actually alcoholic do not exhibit these social effects; instead, they feel some of the physical effects of drinking (e.g., feel sleepy, flushed) but attribute these feelings to factors other than alcohol. The second method is didactic, wherein students are educated about this phenomena (e.g., discussion of alcohol myths, such as “I can’t be outgoing at a party without alcohol,” and placebo effects). Initial reviews (90) suggested demonstrations of the placebo effect (99), but not education about this effect, were associated with reduced alcohol use at short-term follow-up for college males. More recent reviews (96,97) found six of twelve studies supported demonstrations of the placebo effect in producing short-term reductions in alcohol use, with results again more consistent for men than women (100). Although one study (101) suggested education about the placebo effect may have harmful effects for women, two more recent studies (102,103) found demonstrating the placebo effect was associated with reductions in alcohol use for both men and women. Overall, results regarding the efficacy of expectancy challenge interventions are encouraging but mixed and suggest implementation of expectancy challenges in single-gender groups may be more effective than mixed-gender challenges, especially for women (100). Practical issues regarding the demonstration of the placebo effect (i.e., administering alcohol to college students as part of the intervention) may limit wider application of this approach.

Brief Motivational Interventions

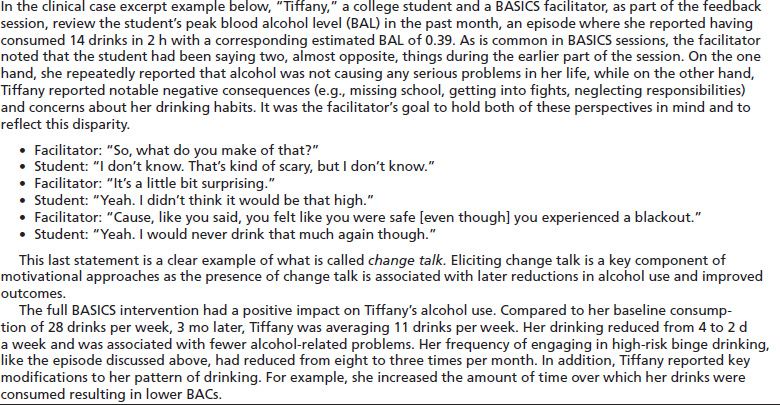

MI, based on the work of Miller and Rollnick (98), is a nonjudgmental, nonconfrontational approach that emphasizes meeting people where they are with regard to their readiness to change. For example, when people are ambivalent about changing a behavior (e.g., problematic alcohol use), MI can be used to explore and resolve that ambivalence; and when people have not yet considered change, MI strategies can be used to prompt thinking about change. There are strong evidence and growing consensus that brief, in-person motivational feedback interventions (typically incorporating assessment and feedback regarding alcohol use, norms, and consequences) or brief motivational interventions (BMIs) are efficacious in reducing and preventing excessive alcohol use and related harm in college populations.(90,91,95–97). Listed in the Task Force report as a Tier I intervention, Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS) developed by Marlatt et al. (107,108) includes a comprehensive assessment followed by a 1-hour personalized feedback interview. The interview is delivered in MI style, using specific strategies such as open questions, reflective listening, summarizing key observations or points, and supporting and affirming the client. The approach is designed to elicit personally relevant reasons for change (i.e., change talk) and the adoption of cognitive–behavioral strategies to implement the desired changes. The interview is structured around a review of graphic feedback generated from the assessment (Table 38-1).

TABLE 38-1 CLINICAL EXAMPLE OF BRIEF MOTIVATIONAL INTERVENTION (BASICS)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree