86

CHAPTER OUTLINE

■ OVERVIEW AND DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

■ PREVALENCE AND PROGNOSTIC EFFECTS OF CO-OCCURRING MOOD AND SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

■ MANAGEMENT OF CO-OCCURRING MOOD AND SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

OVERVIEW AND DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

Significance

Depressive disorders, major depression and dysthymia, are among the most common psychiatric disorders in the general population. Estimates from community surveys show that over 10% of the general population has experienced a depressive disorder at some point in their lifetime, and the prevalence of substance use disorders is increased by a factor or 2 or more among individuals with major depression (1). Major depression is the most common co-occurring psychiatric disorder encountered among patients presenting for treatment for substance use disorders, with lifetime prevalence rates ranging from 15% to 50% across samples studied from various treatment settings (2). Among drug-and alcohol-dependent patients, major depression has been associated with worse outcome, including worse substance use outcome, worse psychiatric symptoms, and increased suicide risk. Clinical trials suggest that treatment of depression among substance-dependent patients with medication or behavioral therapy can improve outcome. Thus, it is very important for clinicians working with substance-dependent patients to be able to recognize and treat depression or make appropriate referrals for treatment.

Bipolar disorder is more rare in the general population, with estimates of the lifetime prevalence of bipolar I disorder ranging from 1% to 3%, another 1% for bipolar II disorder, and 2% or more having subthreshold disorders in the bipolar spectrum, each of which are associated with moderate to severe functional impairment (3,4). Bipolar disorder is correspondingly less common than major depression among samples of patients seeking treatment for substance use disorders in routine outpatient settings. However, the strength of association between bipolar disorders and substance use disorders is larger than for depressive disorders, with the presence of a bipolar disorder increasing the likelihood of a substance use disorder by a factor of 4 or more. Hence, among patients with bipolar disorder, the prevalence of substance use disorders is 40% or more (5), and patients with both substance and bipolar disorders are especially likely to be encountered on inpatient settings or other clinical programs serving psychiatric or dual diagnosis populations. As with unipolar depression, co-occurring bipolar and substance use disorder is associated with worse prognosis, and while clinical trials are more limited, those that have been conducted suggest that proper treatment of bipolar disorder improves substance use outcome. Further, many patients with bipolar disorder (particularly those who have had bipolar disorder for a long time) will present with a depressive syndrome, but the treatment recommendations for bipolar depression are quite different from unipolar depression. For bipolar disorder, mood stabilizer medications (e.g., lithium, valproate, carbamazepine) are the mainstay of pharmaco-therapy, rather than antidepressant medications. Thus, it is very important for clinicians working with substance-dependent patients to be able to recognize bipolar disorder, distinguish unipolar depression from bipolar disorder, and either treat or make appropriate referrals for treatment.

DSM-IV and DSM-5

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) provides the commonly accepted diagnostic criteria for mental disorders. The 4th Edition (DSM-IV) (6) was published in 1994 and has been replaced by the 5th edition (DSM-5) (7), which was published in 2013. This chapter focuses on DSM-IV criteria, since the final version of DSM-5 is not available as of this writing. Further, virtually all the evidence on the prevalence, prognostic, and treatment significance of co-occurring disorders derives from DSM-IV or earlier criteria sets. Preliminary working versions of DSM-5 did not suggest substantial changes to the criteria for mood disorders. DSM-IV advanced the approach to co-occurring disorders by introducing the category of substance-induced mood disorders, distinguishing these from independent mood disorders on the one hand and usual intoxication and withdrawal effects of substances on the other. These key categories (independent disorders, substance-induced disorders, and usual effects of substances), which are an important focus of this chapter, have been retained in DSM-5.

DSM-IV Criteria for Depressive Disorders and Bipolar Disorders

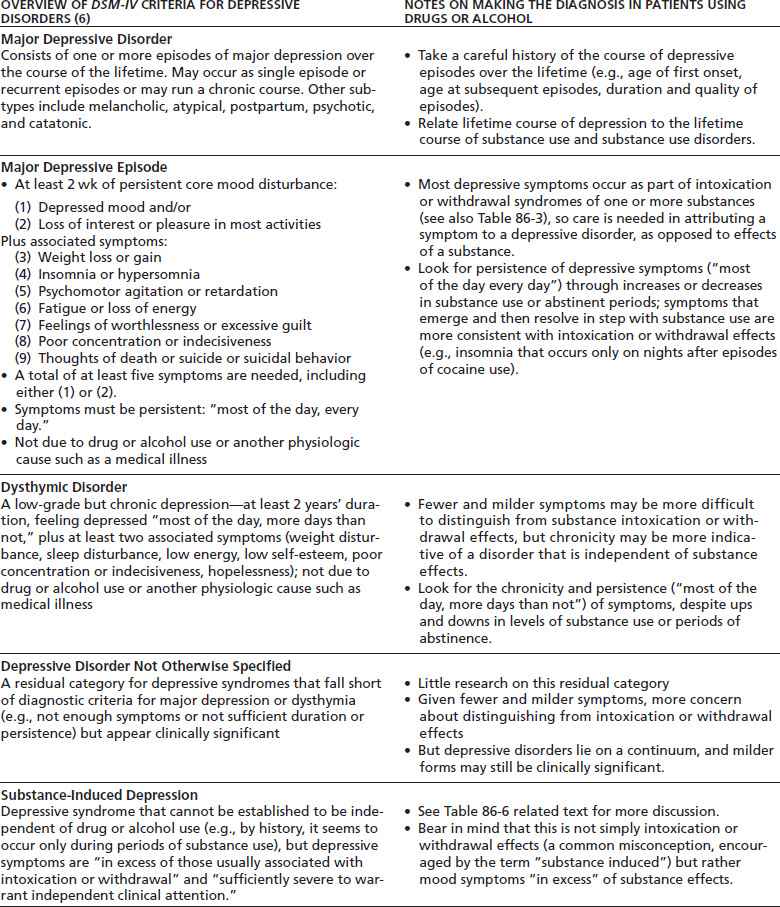

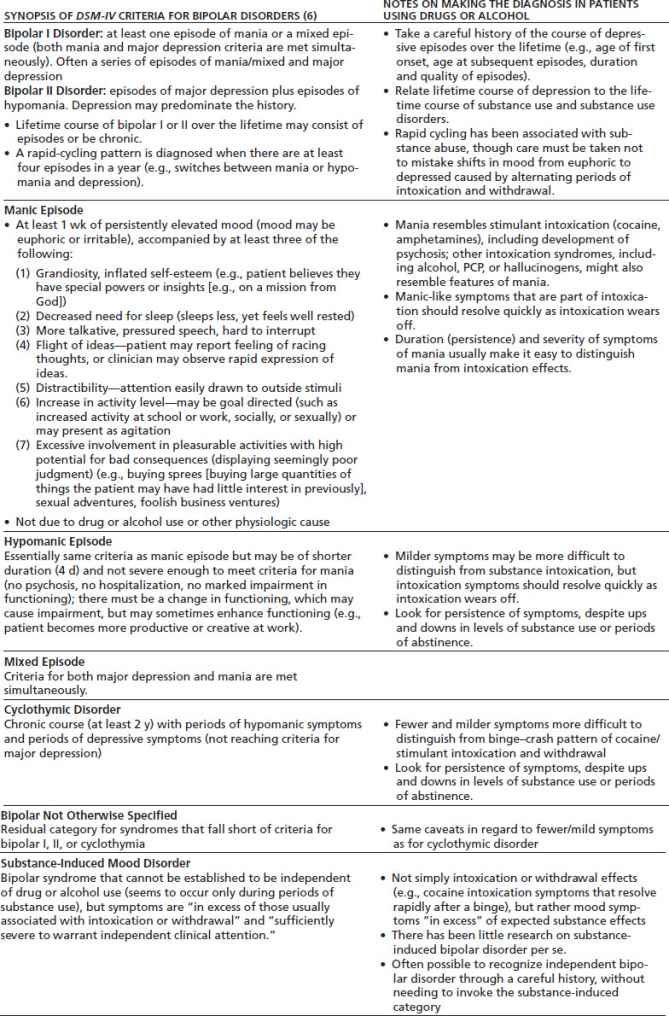

A brief overview of DSM-IV mood disorders (6) is provided in Tables 86-1 and 86-2. Readers who are less familiar with how to take a history to detect these disorders are encouraged to obtain some experience with one of the semistructured psychiatric diagnostic interviews such as the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (8) or the Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders (PRISM) (9). These interviews guide the clinician in how to ask about each of the symptoms and apply the DSM-IV criteria, and practice using them constitutes an excellent training exercise. Mood disorders are divided into depressive disorders (also referred to as unipolar), consisting of single or multiple episodes of major depression or dysthymia, and bipolar disorders, which consist of mixtures across the patient’s lifetime of episodes of depression and episodes of mania, hypomania, or mixed mood states. The distinction of depressive disorders from bipolar disorders is important, because the relationship to substance use differs, and the treatment implications differ in important ways.

TABLE 86-1 SYNOPSIS OF DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR DSM-IV DEPRESSIVE DISORDERS AND IMPORTANT ISSUES TO CONSIDER IN DIAGNOSING DEPRESSIVE DISORDERS IN PATIENTS WHO ARE USING DRUGS OR ALCOHOL

Mood disorders, grouped into depressive disorders and bipolar disorders, consist of combinations of mood episodes (major depressive episode, manic episode, hypomanic episode, mixed episode). For detailed criteria, see the full DSM-IV criteria and accompanying discussion.

TABLE 86-2 SYNOPSIS OF DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR DSM-IV BIPOLAR DISORDERS AND IMPORTANT ISSUES TO CONSIDER IN DIAGNOSING BIPOLAR DISORDERS IN PATIENTS WHO ARE USING DRUGS OR ALCOHOL

Bipolar disorders consist of combinations of mood episodes (major depressive episode, manic episode, hypomanic episode, mixed episode). For detailed criteria, see the full DSM-IV criteria and accompanying discussion.

Depressive Disorders

DSM-IV defines a major depressive episode as a period of persistent, relatively severe depression, with multiple associated depressive symptoms (disturbances in weight, appetite, sleep, energy, cognition, self-esteem, suicidal ideation, etc.), lasting at least 2 weeks, and that interferes with functioning. Dysthymia is a period of milder but chronic depression lasting at least 2 years. Major depressive disorder is diagnosed when there have been one or more major depressive episodes. When interviewing a patient with current depressive symptoms, it is always important to review the lifetime history for past episodes of major depression. Major depression may occur as a single isolated episode, may run a chronic episodic course with multiple recurrences, or may be chronic and unremitting. Major depressive episodes may also be superimposed on a chronic dysthymic pattern. At its most severe, there can be psychosis, often involving delusions of paranoia or guilt (e.g., the patient begins to believe he or she has committed a terrible crime and will be punished). The main risk factors for depressive disorders include a genetic component. This is evidenced by heritability estimates from twin and family studies. Stress (e.g., losses) and trauma are also important risk factors. Thus, in taking a history, it is always important to ask about family history and about stressors and traumatic experiences. DSM-IV also requires that the clinician establish that the depressive disorder is not caused by substance use (abuse, or a medication) or a medical condition (e.g., hypothyroidism, or other systemic illnesses, among others). Thus, a medical history and workup is an important component of the diagnostic evaluation. Finally, when evaluating a patient presenting with a major depressive episode or a syndrome of dysthymia, it is very important to review the history for past episodes of mania, hypomania, or mixed mood episodes. The presence of one of these indicates that the patient has a bipolar disorder.

Bipolar Disorders

Bipolar disorders consist of episodes of major depression or dysthymia, alternating with episodes of mania, or hypo-mania, at some time during the lifetime course. Mania is a severe disturbance consisting of euphoric, expansive, or irritable mood, high energy, less need for sleep (e.g., only a few hours per night), grandiose thinking (e.g., believing one has special powers, religious revelations), and increased speech and activity level. Functioning is severely impaired with disorganized, inappropriate behavior, and patients often become psychotic with hallucinations and delusions that may be grandiose (“I am the messiah”) or paranoid (“the CIA is after me”). Mixed states also occur, in which the patient meets criteria for both mania and major depression during the same episode. Hypomania is a milder form of mania, without psychosis and with less functional impairment. In some cases, functioning improves during hypomania with high levels of productivity and creativity. In most cases of bipolar disorder, depressive episodes are predominant with less frequent mania or hypomania. Thus, patients with bipolar disorder often present with major depression, or dysthymia, and a careful lifetime history is needed to determine whether there have been past episodes of mania or hypomania. It is also useful to interview family members about this, since patients themselves often have little insight during mania or hypomania and may not experience these states as abnormal. As with depressive disorders, genetics, stress, and trauma are risk factors, so that family history and history of stress and trauma exposure are important. DSM-IV requires the clinician to rule out drugs (particularly stimulants), medications, or medical illnesses that might mimic bipolar disorder symptoms (e.g., hyperthyroidism).

Distinguishing Substance-Related Mood Symptoms from Mood Disorders

The problem of distinguishing mood symptoms caused by substance intoxication or withdrawal or chronic exposure to substances, from bona fide mood disorders, is one of the pivotal challenges for clinicians working with substance-abusing patients. Hence, it is a central focus of this chapter. Mood symptoms (e.g., sadness, apathy, irritability, pessimism, hopelessness, fatigue, appetite changes, anxiety, insomnia or hypersomnia, euphoria, hyperactivity) are extremely common among patients with drug or alcohol use problems. Often, such symptoms are components of substance intoxication or withdrawal and will resolve with abstinence; in that case, the indicated treatment is aggressive treatment of the substance problem. At other times, the mood symptoms are components of an independent mood disorder that needs to be treated in addition to treating the substance problems.

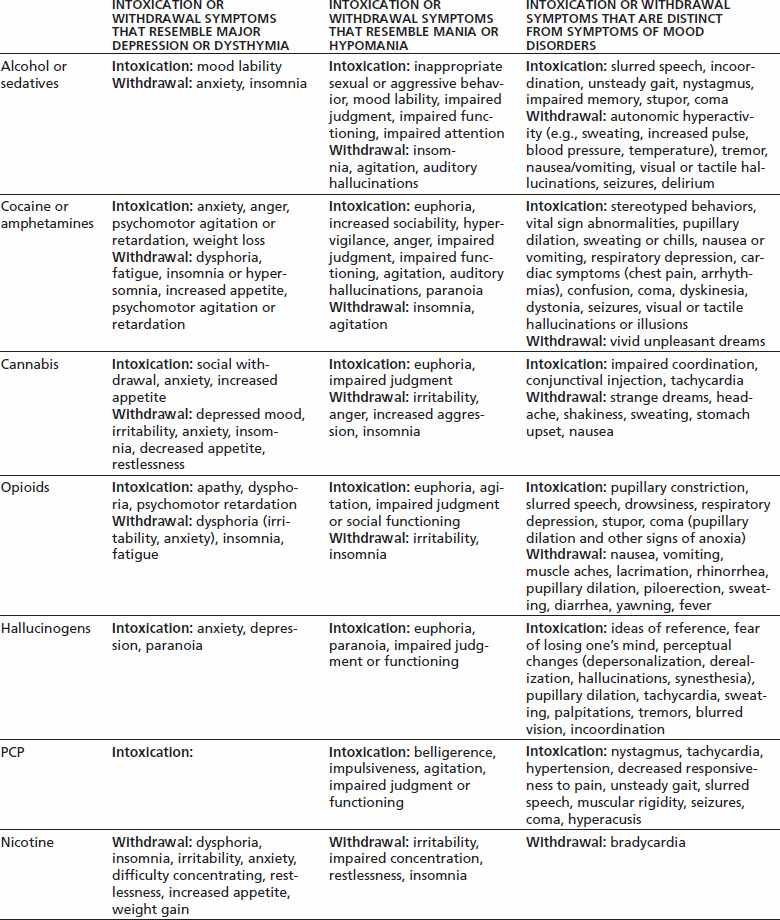

Table 86-3 provides a summary of the overlap between symptoms of substance intoxication and withdrawal as listed in DSM-IV and DSM-IV symptoms of unipolar and bipolar mood disorders (6). Cannabis withdrawal, although not included in DSM-IV, has been added, since it is now well characterized (10) and likely to be included in DSM-5. As can be seen, there is considerable overlap. It is a worthwhile exercise to review the descriptions in DSM-IV (and the criteria) of the various substance intoxication and withdrawal syndromes. Further, it is clear that chronic substance exposure, perhaps in combination with the high level of stress frequently characterizing the lifestyle of an addicted individual, often results in considerable depressive symptoms beyond what is listed among DSM-IV intoxication and withdrawal symptoms. This is part of what prompted the creation of the syndrome of substance-induced depression in DSM-IV (6).

TABLE 86-3 SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES BETWEEN DSM-IV INTOXICATION OR WITHDRAWAL SYMPTOMS AND SYMPTOMS OF DSM-IV MOOD DISORDERS

Note: The table lists DSM-IV symptoms for intoxication or withdrawal from each of the main substance classes and shows where there is overlap with similar symptoms of DSM-IV depressive syndromes (major depression, dysthymia) in column 2 or bipolar syndromes (mania, hypomania) in column 3; column 4 lists intoxication and withdrawal symptoms that are not consistent with mood disorder symptoms and would be helpful to distinguish substance effects from mood disorders.

Abstinence or Initiation of Substance Treatment Improves Depression

This point cannot be overemphasized. Studies among alcohol- (11–13), opioid- (14), and cocaine-dependent patients (15,16) have documented elevated scores on depression symptom scales that improve substantially after initiation of abstinence upon treatment entry, such as hospitalization for detoxification or initiation of methadone maintenance. Thus, initiation of treatment for the substance use problem and efforts to achieve abstinence should always be a first step in the treatment of a patient with co-occurring mood and substance use disorders.

Some Cases of Depression Will Persist Despite Abstinence or Substance Treatment

This point deserves equal emphasis. Despite abstinence, or reductions in substance use, some cases of depression will persist. Evidence suggests that a careful clinical history can distinguish mood disorders that are independent of substance use and will persist in abstinence from those that will resolve with abstinence. For example, in a now classic series of studies, Brown and Schuckit (12,17) divided alcohol-dependent patients entering a 4-week inpatient stay into those with no history of mood disorder, those with a “secondary” mood disorder (onset after the onset of alcohol dependence), and those with a “primary” mood disorder (mood disorder onset prior to the onset of alcohol dependence). All three groups had substantially elevated Hamilton Depression Scale (HDS) scores at the outset. After 1 to 2 weeks of abstinence, the groups with no mood disorder or a secondary mood disorder experienced reductions of over 50% in their HDS scores with scores dropping into the normal or mildly depressed range, no specific treatment for depression needed. However, in the group with primary mood disorder, there was no change in the depression scores over 3 weeks of abstinence, and two-thirds of those patients had HDS scores greater than 20 after 3 weeks of abstinence, consistent with severe depression. For these patients, aggressive treatment of the alcohol dependence did not take care of the depression, and most clinicians and researchers would now agree that these patients with primary depression, identified with a careful lifetime psychiatric history, need to receive treatment for their depressive disorder, in addition to continued treatment for the alcohol dependence.

Importance of the Clinical History

Controversy over how to make these distinctions between mood symptoms caused by substances and mood symptoms that are part of a true mood disorder has characterized the field since the inception of modern psychiatric diagnosis. This is discussed at greater length below in the section on Differential Diagnosis. The field has expanded from a narrower view of a “primary” disorder as having prior onset, as in the study of alcohol-dependent patients cited above (17), to a broader view articulated in the DSM-IV of independent mood disorders having prior onset or persistence despite a period of abstinence sufficient to rule out substance effects (6). For example, we recently showed that a past history of an independent mood disorder, according to DSM-IV and as operationalized with the PRISM interview (9), distinguished cases of major depression that would persist during abstinence over a 1-year follow-up in a sample of treatment-seeking substance-dependent patients (18). The point to emphasize here is that, in addition to efforts to initiate substance abuse treatment and help the patient attain abstinence, a careful clinical history can help select those patients with independent mood disorders. The history should examine the course of mood symptoms in relation to substance use over the patient’s lifetime, looking particularly for onset of a mood disorder syndrome prior to the onset of substance problems, as in the study of alcohol dependence described above (17), or the persistence or emergence of a mood disorder during abstinent periods over the lifetime, consistent with the DSM-IV construct of an independent (as opposed to a substance-induced) mood disorder.

Overview of the Chapter

The balance of this chapter covers in more detail the epidemiology, differential diagnosis, and treatment of co-occurring mood and substance use disorders. The section on epidemiology examines the prevalence and prognostic significance of co-occurring mood and substance use disorders in community samples and clinical samples typically encountered by practitioners. The next section presents an approach to differential diagnosis of mood disorders in the setting of substance abuse, based on DSM-IV and the latest evidence on diagnostic approaches. The final sections present evidence on treatment for depressive and bipolar disorders co-occurring with substance use disorders. It is hoped that this chapter will provide a useful clinical guideline for physicians and other practitioners working with substance-abusing patients as well as an introduction to the evidence base in the research literature and the gaps in research that need to be filled to further advance the field.

PREVALENCE AND PROGNOSTIC EFFECTS OF CO-OCCURRING MOOD AND SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

Since interest in the co-occurrence of mood and substance use disorders began to increase in the 1960s and 1970s, many studies have been published examining the prevalence of mood disorders among substance-dependent samples. The initial generation of studies examined patients being admitted to treatment services for substance use disorders (e.g., inpatient detoxification or rehabilitation units, methadone maintenance clinics). These are particularly useful in establishing the scope of the clinical problem and (when follow-up data were gathered) the prognostic effects. However, in regard to etiology, studies of clinical samples would tend to overestimate the magnitude of association between mood and substance use disorders because of Berkson’s bias, namely, that high rates of comorbidity can be an artifact of treatment seeking, rather than a reflection of a direct relationship between the disorders (19). For example, depression might drive substance-dependent patients to seek treatment, accounting for its high prevalence among treatment seekers without any direct etiologic relationship between the disorders. Studies of comorbidity in community samples drawn from the general population represented a substantial advance in part because they circumvent Berkson’s bias. These prevalence studies are also important because they show the evolution of diagnostic methods for addressing the problem of distinguishing mood symptoms from mood disorders, introduced above, and the development of the DSM-IV approach to co-occurring disorders, presented below in the section on Differential Diagnosis.

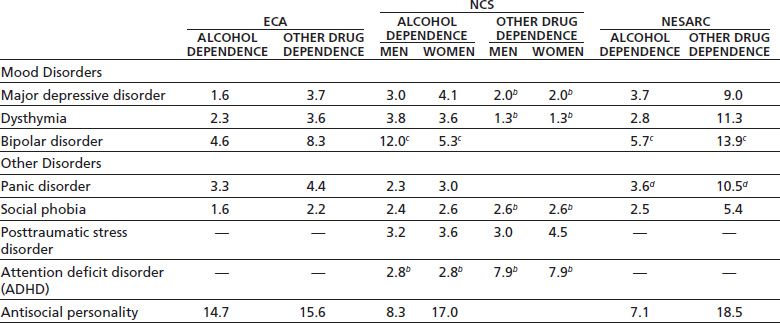

General Population

Four major studies of the prevalence of psychiatric disorders among community samples drawn from the general population have been conducted in the United States over the recent decades, namely, the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study (20), the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) (21,22), the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey (NLAES) (23,24), and the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) (1,3). Table 86-4 summarizes data from ECA, NCS, and NESARC on co-occurrence of mood disorders with alcohol and drug dependence. NLAES data, not shown in Table 86-4, had similar findings for the co-occurrence of major depression and alcohol and drug use disorders but did not include other disorders (bipolar, anxiety, etc.). The data are expressed as odds ratios, which reflect the multiple by which one disorder increases the prevalence rate of the other, hence the strength of association between disorders. For example, an odds ratio of 1.0 indicates that among individuals with a substance-dependence disorder, the odds (which can be roughly equated with prevalence) of a mood disorder is the same as in individuals without a substance-dependence disorder; an odds ratio of 2.0 indicates that among individuals with a substance-dependence disorder, the prevalence of a mood disorder is about twice that observed among those without substance dependence.

TABLE 86-4 ODDS RATIOSa REFLECTING THE STRENGTH OF ASSOCIATION OR CO-OCCURRENCE BETWEEN ALCOHOL OR DRUG DEPENDENCE DISORDERS AND AFFECTIVE AND OTHER SELECTED DISORDERS FROM THREE COMMUNITY SURVEYS

Note: Data taken from three community surveys: the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study, the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS), and the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC); odds ratio can be interpreted roughly as the multiple by which the prevalence of a disorder across the rows (major depression, dysthymia, etc.) is increased when alcohol or drug dependence is present, compared to individuals without alcohol or drug dependence.

a ECA and NCS report odds ratios on lifetime prevalences of co-occurring disorders; NESARC reports odds ratios on 12-month prevalences of co-occurring disorders.

b For these co-occurring disorders in NCS, odds ratios are reported for men and women combined.

c For NCS and NESARC, odds ratios are for bipolar I disorder with a history of full mania.

d For NESARC, odds ratios shown are for panic disorder with agoraphobia; odds ratios for panic disorder without agoraphobia were similar.

As can be seen in Table 86-4, odds ratios are at least 2.0 for most combinations of disorders, showing that the presence of alcohol or drug dependence at least doubles the odds of a mood disorder, or other disorder, being present. It is notable that the odds ratios for major depression and dysthymia are similar. Thus, while dysthymia is often thought of as a mild version of depression, it should not be discounted in the clinical evaluation; the hallmark of dysthymia is its chronicity, and the presence of chronic depressive symptoms across the course of a substance use disorder, even if the depressive symptoms are milder, should be taken seriously.

For bipolar disorder, the odds ratios are substantially larger than for major depression or dysthymia. When depressive symptoms are present, it is very important to search the history carefully for past episodes of mania or hypomania, since bipolar illness has a particularly strong association with substance use disorders, and it has specific treatment implications that differ from those for unipolar depression. When evaluating a patient with bipolar illness, it is especially important to inquire about substance use problems, as they are likely to be present and to complicate the clinical course.

Common anxiety disorders (social phobia, panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, and posttraumatic stress disorders [PTSD]) are also shown in Table 86-4 to illustrate that these too have substantial associations with substance use disorders, of at least the same magnitude as major depression or dysthymia. These particular disorders frequently co-occur with major depression or dysthymia and respond to the same antidepressant medications. Further, their cardinal symptoms (fear of social interactions, spontaneous panic attacks and fear of public places, and reexperiencing symptoms triggered by reminders of traumatic events) are distinctive and not attributable to substance toxicity or withdrawal. Thus, when a substance-dependent patient presents with depression, the history should include a detailed inquiry for each of these anxiety disorders. Their presence can be very useful in ruling out substance intoxication or withdrawal as the sole source of mood symptoms. In a patient with chronic substance abuse, it is often difficult to establish in the history whether depressive symptoms are independent of substance use, since so many of those symptoms may be toxic or withdrawal effects of substances. However, the presence of one of these anxiety syndromes strongly suggests the presence of an independent disorder, warranting specific treatment.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), also shown in Table 86-4, has strong associations with alcohol and drug dependence as well, with odds ratios of 2.8 and 7.9, respectively (25). It is also strongly associated with major depression (odds ratio = 2.7), dysthymia (odds ratio = 7.5), and bipolar disorder (odds ratio = 7.4) (25). The symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity begin in early childhood and can often be recognized in the history as problems with school performance in elementary school, well before the onset of drug or alcohol use. A simple question to ask during the clinical history is “Tell me what elementary school was like for you,” and then follow up with questions about whether the patient remembers feeling uncomfortable sitting quietly in class, having trouble paying attention to the teacher, daydreaming, trouble staying organized, or getting in trouble for being too active and disrupting the class. The symptoms, particularly poor attention and poor organization skills, often persist into adulthood and are responsible for substantial functional impairment and poor role performance during adulthood (e.g., poor job performance, high divorce rate). This in turn lends itself to the development of depression. Detailed reviews of the comorbidity, diagnosis, and treatment of ADHD among substance-dependent patients can be found elsewhere (26,27) and in the corresponding chapter in this text. In summary, when evaluating a substance-dependent patient with symptoms of depression, it is important to look for ADHD in the history and consider specific treatment of the ADHD, if present.

Antisocial personality is included in Table 86-4 to illustrate its strong association with substance use disorders. Substance-dependent patients will often have antisocial features, but it is important to bear in mind that the presence of antisocial features, or disorder, does not rule out the presence of a mood or anxiety disorder, and in fact, they often co-occur.

Substance Use Disorder Treatment Populations

Numerous studies have been published examining the prevalence of mood disorders among patients admitted to alcohol or drug treatment programs, mainly inpatient detoxification or rehabilitation units, outpatient programs, or opioid maintenance programs. Reviews of this literature (2) show lifetime prevalence rates of major depression ranging from 20% to 50%, with rates of current major depression in the 10% to 20% range, substantially exceeding rates found in the general population. Bipolar disorder is less common in these samples, consistent with its low prevalence rate in the general population. Thus, clinicians seeing patients in these typical addiction treatment settings should expect to see high rates on co-occurring depression but should also remain alert for cases of bipolar disorder.

Prognostic Effects

A number of these studies have included a longitudinal follow-up, examining prognostic effects of co-occurring major depression on substance use outcome. A review of this literature (2) shows that studies examining a lifetime diagnosis of major depression (i.e., major depression at any point during the lifetime) found little prognostic effect. In contrast, a current diagnosis of major depression has been consistently associated with worse outcome of substance use problems over follow-up periods ranging from 6 months to 5 years. This adverse prognostic effect holds for major depression diagnosed at an initial evaluation (28–32) and for major depression diagnosed during the follow-up period (32–34), among alcoholics (30–35), methadone-maintained opioid addicts (28,29), and cocaine-dependent patients (32,36).

Another important pattern in the results from longitudinal studies is that current depressive symptoms, as measured by an elevated score on a standard scale such as the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) or Hamilton Depression Scale (HDS), have inconsistent prognostic effects (2). For example, in a study of alcohol-dependent inpatients, Greenfield et al. (30) showed that an elevated HDS score at baseline was not associated with outcome across a 1-year follow-up, whereas a diagnosis of major depression at baseline predicted relapse to heavy drinking during follow-up; the risk of alcohol relapse was reduced among patients who were treated with antidepressant medication during the follow-up period. Dysthymia (i.e., low-grade chronic depression) has received little study in terms of its prognostic effects on substance use outcome. However, there is some evidence that depressive symptoms have adverse prognostic effects when they persist during or after treatment of a substance use disorder (37,38). This suggests that persistent depressive symptoms, even if not meeting criteria for major depression, should be taken seriously among substance-dependent patients. Depressive symptoms among patients with co-occurring bipolar disorder and alcohol dependence have been associated with subsequent increased heavy drinking (39).

Taken together, these data have clear clinical implications. Depression symptom scales such as the Beck or Hamilton can be useful as screening tools, but these need to be followed up with a careful clinical history, establishing presence or absence of depressive disorder. A past history of a depressive disorder is important information, as it indicates increased risk for depression in the future, but it is current major depression that is most clearly associated with worse outcome among substance-dependent patients and should be attended to in the treatment plan. Chronic low-grade depression (dysthymia) and depression that persists after initiation of treatment for the substance problem also warrant clinical attention.

Psychiatric and Primary Care Populations

Among patients presenting in psychiatric and primary care treatment settings for treatment of depression, the prevalence of substance use disorders depends upon the setting and associated severity of the mood disorder. In the STAR*D study, which evaluated and treated over 4,000 outpatients with major depression in community-based psychiatric and primary care clinics, the prevalence of concurrent alcohol use disorders was 13% and drug use disorders 8%, and a current substance use disorder was associated with a positive family history of substance use disorder (40). Such rates are modest but exceed what would be expected from general population surveys. Among psychiatric inpatients, a more severely ill group, substance use disorders are common among both patients with major depression and bipolar disorder (41). Substance use disorders are common among patients in treatment for bipolar disorder, with rates of current substance use disorders of 30% or higher (5,41). The co-occurrence of mood and substance use disorders may be especially common among patients with serious co-occurring medical disorders such as HIV (42,43).

It is increasingly clear that the majority of individuals with substance use disorders, depression, and other common mental disorders do not present at specialty treatment settings such as substance abuse treatment programs, or even psychiatric clinics. Instead, they often present at the offices of primary care physicians, where substance abuse and depression are more likely to go undetected, and may be associated with over- or underutilization of services and poor outcome (44). Patients may be unaware of these problems or may avoid discussing them with health care providers because of the considerable stigma attached to the idea of having a “psychiatric” problem. This presents an important challenge to addiction specialists, suggesting the need to reach out to these other settings with programs of screening and brief intervention (45).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Etiologic Relationships between Mood and Substance Use Disorders

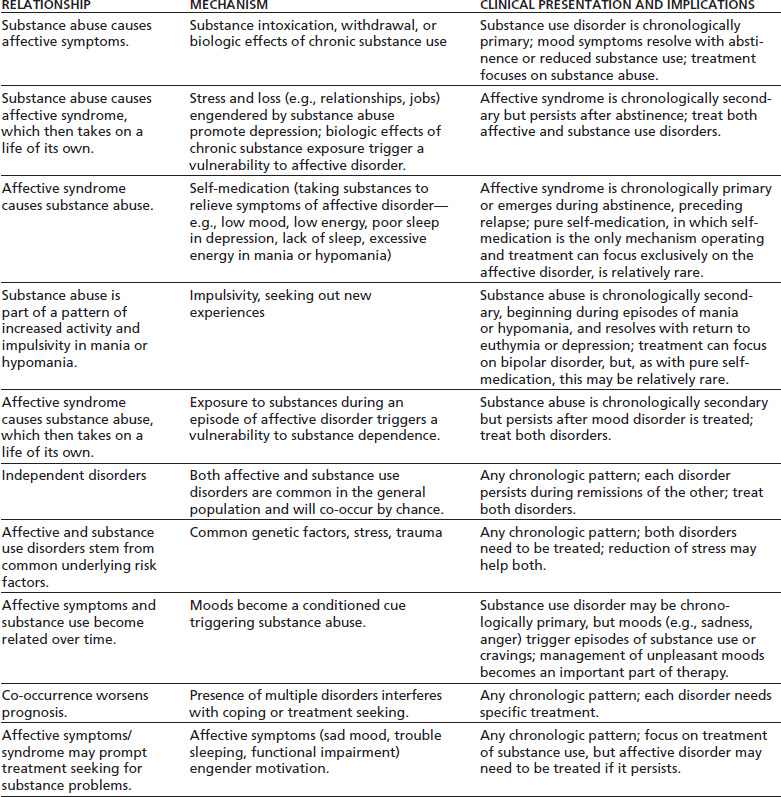

Beneath the problem of how to diagnose and treat mood symptoms among substance-dependent patients lies the issue that there are multiple different potential etiologic relationships between mood symptoms or syndromes and substance use disorders. A summary of these is presented in Table 86-5, along with possible underlying mechanisms and implications for diagnostic assessment and treatment. A complete review is beyond the scope of this chapter, but each of these relationships and mechanisms has some evidence to support it. In the diagnostic evaluation of a patient with co-occurring disorders, it is useful to think about which of the options in Table 86-5 may be operating. Table 86-5 also serves to illustrate the complexity involved in co-occurring disorders, particularly when one considers that several of these causal pathways or mechanisms might operate at once.

TABLE 86-5 SUMMARY OF POSSIBLE ETIOLOGIC RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN CO-OCCURRING AFFECTIVE SYMPTOMS/SYNDROMES AND SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

There are two important clinical implications here. The first is to appreciate the potential complexity and to avoid viewing patients in simplistic terms. All mood symptoms are not caused by toxic and withdrawal effects of substances, nor is all substance abuse a result of underlying psychopathology (as in “self-medication”). The second point is to be cautious in formulating causal mechanisms between co-occurring disorders. For any given patient, it may be difficult to establish which of several causal mechanisms may be operating. For example, when depression resolves with treatment of the substance use disorder and reduction in substance use, this is consistent with the inference that depression was a toxic effect of substance abuse. However, it is also possible that there was an independent mood disorder that responded to supportive elements of the behavioral therapy used to treat the substance use disorder, only to reemerge at some future point.

DSM-IV Independent versus Substance-Induced Mood Disorders

Prior to DSM-IV, there were several classifications for co-occurring disorders in the literature. These included “primary” versus “secondary,” which sometimes referred to the order of first onset—a major depressive disorder would be considered primary if its age at onset preceded the age at onset of a substance use disorder and secondary if the substance disorder came first. “Primary” was also used in a more loose sense to convey causality—the primary disorder is the main disorder, which drives any secondary disorders. In DSM-III an “organic mood disorder” could be used to categorize a mood disorder caused by substance abuse.

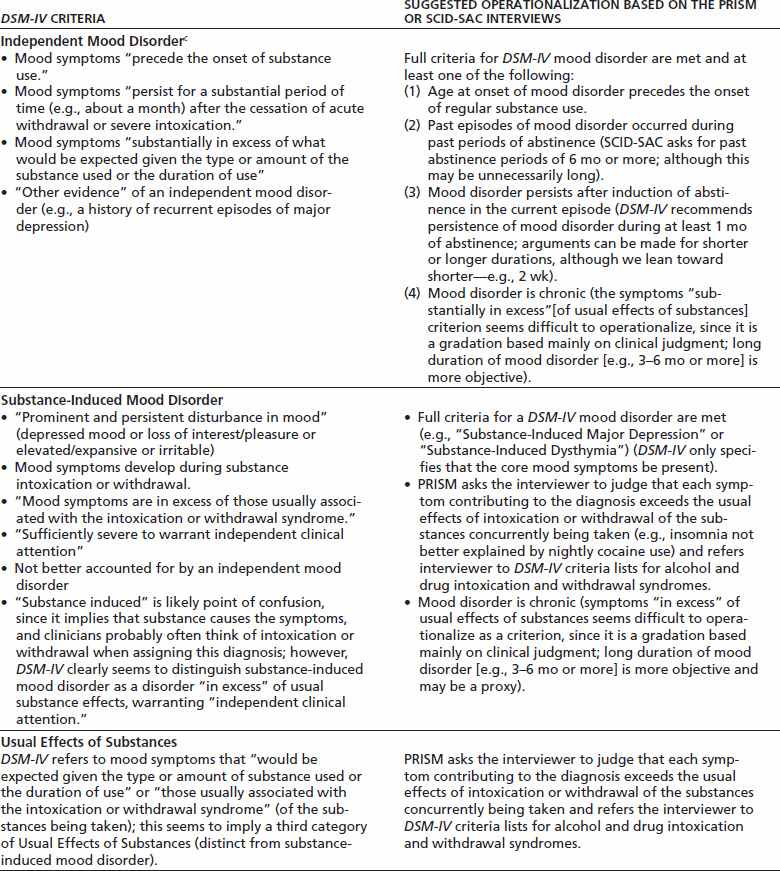

The DSM-IV committee on substance use disorders forged a substantial advance for the field by synthesizing pre–DSM-IV approaches to define primary or independent mood disorders and creating a new category of substance-induced mood disorder within the larger section on Mood Disorders. Thus, co-occurring mood disorders in the setting of substance abuse can be categorized as “independent” of substance use, or “substance induced.” Because substance-induced mood disorder is defined as representing mood symptoms that are in excess of the usual effects of substance intoxication or withdrawal, we also recommend construing a third category of “usual effects of substances,” referring to intoxication and withdrawal effects that would be expected given the type(s) and pattern of a patient’s use of substances. The DSM-IV criteria, and our interpretation of them, are summarized in Table 86-6. Because the DSM-IV criteria, as stated, leave some details vague, a suggested operationalization is also included in Table 86-6, based on the SCID-SAC (46) and PRISM interviews (9,34).

TABLE 86-6 SUMMARY OF DSM-IV SCHEME FOR CLASSIFYING CO-OCCURRING MOOD AND SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERSa AND SUGGESTIONS FOR OPERATIONALIZATION OF CRITERIA BASED ON SCID-SAC OR PRISM INTERVIEWSb

a For a complete statement of the criteria, see American Psychiatric Association section on substance-induced mood disorder (6,7).

b Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV , Substance Abuse Comorbidity Version (SCID-SAC) (46); Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders (PRISM) (9).

c DSM-IV terms this “mood disorder that is not substance-induced,” but in the literature, it is commonly referred to as either “independent” or “primary.”

Independent Mood Disorder

Also referred to in the literature as “primary,” DSM-IV defines an independent mood disorder as one that precedes the onset of substance abuse or persists during significant periods of abstinence (1 month or more is suggested as the minimum). We have found that the historical data needed to establish these criteria (ages at onset, presence of periods of abstinence, and mood syndromes occurring during abstinent periods) can be determined with good reliability from a clinical history (46) and have established good reliability for the categorical diagnosis with both a modified SCID (46) and the PRISM diagnostic interviews (9).

Substance-Induced Mood Disorder

The category of substance-induced mood disorder was established to recognize the phenomenon of co- occurring mood syndromes that cannot be established as chronologically independent of substance use, yet the mood symptoms seem to exceed what would be expected from mere intoxication or withdrawal effects from the substance(s) the patient is taking. A typical example would be a patient with a long-standing, chronic history of substance abuse, who also has a syndrome consistent with major depression that has occurred only during substance use, yet the syndrome seems substantial enough to warrant clinical attention and perhaps specific antidepressant treatment.

Expected Effects of Substances

When evaluating patients with co-occurring substance use and mood symptoms, we recommend that this third category “expected effects of substances” (intoxication and withdrawal effects, as defined in DSM-IV) be explicitly considered in the differential diagnosis. DSM-IV clearly specifies that the symptoms of either an independent or a substance-induced mood disorder must exceed the expected effects of intoxication or withdrawal from the substances the patient is taking (see Tables 86-1 to 86-3). The term “substance-induced” is somewhat confusing in that it implies cause and effect (substances causing mood symptoms). Thus, clinicians commonly use “substance-induced” to describe intoxication or withdrawal effects, when DSM-IV excludes these from a diagnosis of substance-induced mood disorder. Thus, we have recommended a more neutral term such as “substance-associated” or “substance-nonindependent” might be considered to replace “substance-induced” (47).

It is true that a DSM-IV substance-induced mood disorder should, by definition, resolve if abstinence is achieved. On the other hand, it has been shown that if specific criteria are set for making the diagnosis (e.g., the mood disorder has historically never occurred independent of substance use, but full criteria for major depression are met), a substantial proportion of such cases will persist during future abstinent periods, thus converting to an independent depression (18,48). Thus, DSM-IV substance-induced depression, depending on how it is operationalized, may represent cases in which the status (independent vs. not independent of substance use) is uncertain at present. This highlights the importance of identifying and following substance-induced depression, as it may convert to independent depression over time and as efforts are made to reduce or eliminate substance use.

Diagnostic Methods and Predictive Validity of DSM-IV Approach

One of the problems with the DSM-IV approach is that the criteria are left vague in some respects, particularly in regard to substance-induced mood disorder. Table 86-6 highlights those symptoms that are left vague and suggested operationalized criteria in the second column. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (8) includes a module for substance-induced mood disorder, but it essentially asks the interviewer to make a clinical judgment based on the criteria. The PRISM (9,34) is a semistructured interview that was designed specifically to evaluate mood and other co-occurring psychiatric disorders in the setting of substance use disorders. PRISM provides more specific criteria for substance-induced mood disorder and its distinction from an independent mood disorder on the one hand or usual effects of substances on the other; these criteria are reflected in the suggested operationalizations in Table 86-6. To make a diagnosis of substance-induced mood disorder, PRISM requires full criteria for a mood disorder (e.g., major depression, or dysthymia) to be met and that each symptom contributing to the diagnosis (e.g., insomnia, loss of appetite, low energy) exceed the expected effects of the substances that the patients are taking; the interviewer is referred to the DSM-IV criteria sets for intoxication and withdrawal syndromes for the various substances (see Tables 86-1 and 86-2 for symptoms likely to overlap between mood and substance intoxication/withdrawal).

Thus, PRISM establishes criteria for substance-induced mood disorder that are more specific and stringent than those required by the letter of DSM-IV. Evidence for the predictive validity of the PRISM operationalizations comes from a longitudinal study of substance-dependent patients interviewed with the PRISM at an index hospitalization on a dual diagnosis inpatient unit and then followed for 1 year (18,34). About half of this sample had a current major depression. About half of the major depressions were diagnosed as independent and half as substance induced in the current episode. Thus, as experienced clinicians might expect, the prevalence of substance-induced depression in this population was high. A PRISM diagnosis of substance-induced major depression was associated with failure of the substance use disorder to remit, while a diagnosis of independent mood disorder during a period of abstinence in the follow-up was associated with a greater risk of relapse to substance abuse (34); this pattern was consistent across alcohol-, opioid-, and cocaine-dependent patients in the sample (32). Both disorders were associated with suicidal behavior or ideation (49). Further, of those cases diagnosed with a current substance-induced major depression, more than half converted into an independent major depression over the 1-year follow-up by being shown to persist during at least a 1-month period of abstinence (18). Another study, using similar diagnostic methods, found a similar high rate of conversion to independent depression over a longitudinal follow-up (48). When predictors of the likelihood of depression occurring over the course of the 1-year follow-up were examined, a past history of independent major depression and the presence of concurrent anxiety disorders were both associated with increased likelihood of depression (18).

In summary, the data from this longitudinal study (18,34,49) suggest that the PRISM operationalizes DSM-IV substance-induced major depression in a way that predicts both worse substance use outcome and worse depression outcome and in fact often ends up converting to independent major depression during a follow-up period. The data also highlight the importance of examining the history for the presence of anxiety disorders, which also increased the likelihood of depression during the follow-up. While more research is needed to examine other potential ways to operationalize it, the PRISM method appears to identify a form of substance-induced depression that is consistent with the spirit of the DSM-IV, namely, that it is a clinical syndrome that warrants independent clinical attention.

Ries et al. (50) tested a much simplified method of operationalizing the DSM-IV approach to co-occurring mood disorders. Specifically, they created a Likert-type scale that asks the evaluating clinician, after completing the clinical history, to rate the degree to which a mood disorder is independent or substance induced. This is reminiscent of the SCID approach, asking the clinician to make a global judgment of independent versus substance induced. Mood disorders rated toward the substance-induced end of the spectrum were more likely to remit but were also associated with suicidal ideation and risk (51). This work suggests that the judgment of experienced clinicians can be relied upon to make valid distinctions between substance-induced and independent mood disorders. However, experience with psychiatric diagnosis supports erecting criteria that are as objective as possible in order to maximize reliability and validity.

Diagnosing Bipolar Disorder in the Setting of Substance Abuse

Intoxication with cocaine or other stimulants may resemble mania in regard to irritability, grandiosity, hyperactivity, talkativeness, impulsivity, insomnia, and paranoia. The impulsivity of alcohol or sedative intoxication may sometimes also resemble that of mania (see Table 86-3). However, full-blown mania (see Table 86-2) must last for at least a week, during which the symptoms should be persistent, whereas symptoms of intoxication are usually intermittent. For example, in mania, high energy and other symptoms can go on for days despite little or no sleep. In contrast, in cocaine intoxication, these symptoms usually last a matter of hours after cocaine use and are followed by a crash with increased sleep and low energy. Further, the marked impairment or psychosis required for mania is usually well in excess of what would be produced by intoxication. For example, cocaine intoxication may produce paranoia that lasts for a few hours and resolves during the crash period, whereas the psychosis characteristic of mania, often either paranoid or grandiose, is persistent over days and weeks. Hence, in establishing a diagnosis of mania, persistence of symptoms over time and severity of impairment are key markers, as well as occurrence of the symptoms during clear periods of abstinence. Frank mania is distinctive, despite ongoing substance use.

Hypomania, which involves the same core symptoms as mania, but may be briefer (at least 4 days) and with less impairment in functioning, may be more difficult to distinguish from substance intoxication or withdrawal effects. The same is true of cyclothymia, which may be difficult to distinguish from alternating periods of intoxication and withdrawal, mimicking hypomanic and depressive symptoms respectively (see Table 86-2). Thus, it is particularly important to try to establish episodes of the mood disturbances during periods of abstinence, or predating onset of substance abuse, according to the DSM-IV criteria for independent mood disorder.

Rapid-cycling bipolar disorder is diagnosed when there have been at least four mood episodes over the past 12 months, punctuated either by periods of remission or by switches in polarity (from mania to depression, or vice versa) (6). On the order of 20% of cases of bipolar disorder are rapid cycling, and the pattern is associated with greater impairment and poorer response to treatment (52,53). Some evidence suggests that the rapid-cycling subtype is associated with increased prevalence of substance use disorders (54). Thus, it is important to look for this pattern in the history. However, as for hypomania or cyclothymia, a pattern or multiple switches in mood states becomes more difficult to distinguish from the ups and downs of substance intoxication and withdrawal. It is important to establish in the history that hypomanic or manic syndromes have persisted over days or weeks before switching to depression, as well as seeking to establish occurrence of the symptoms during periods of abstinence.

Substance intoxication is likely to exacerbate the dis-inhibition and poor judgment associated with mania and is associated with poor medication adherence (55), which promotes relapse. Thus, patients who present to emergency departments or other acute psychiatric settings with worsening mania are likely to also have substance abuse in the clinical picture.

For most patients with bipolar disorder, particularly those who have had the disorder for an extended period of time, the clinical course predominantly consists of depression, with occasional episodes of mania or hypomania. Thus, in a depressed patient with substance abuse, it is important to carefully review the past history for episodes of mania or hypomania that would indicate that the diagnosis is bipolar disorder. In patients with chronic substance abuse, in whom it is difficult to establish the presence of independent mood symptoms, clear-cut episodes of mania or hypomania, because they are distinctive from the usual effects of substances, are valuable in establishing that an independent mood disorder is indeed present and in need of treatment.

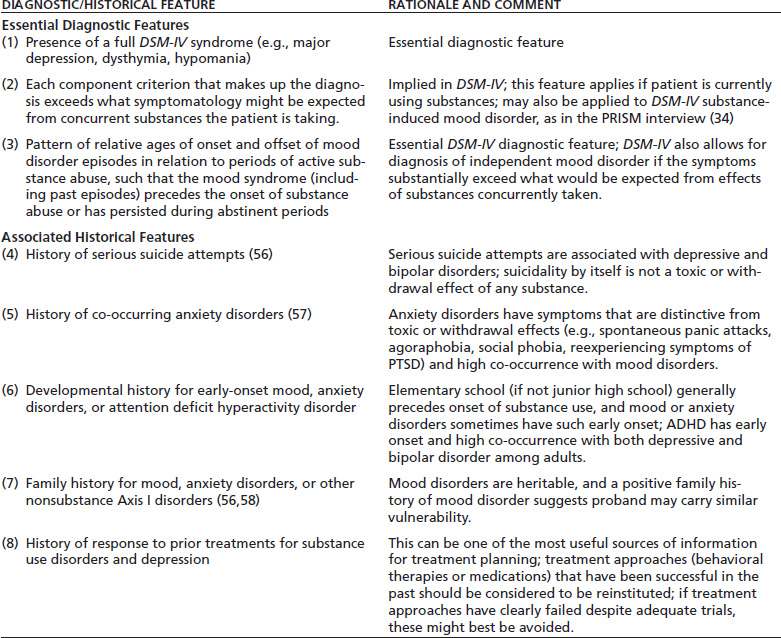

Summary of Recommendations for Diagnosis of Co-Occurring Mood Disorders

The key challenge for the evaluating clinician is to differentiate mood disorders that are independent of substance use and are likely to require specific antidepressant or mood stabilizing treatment from those syndromes that represent toxic or withdrawal effects of substances and are likely to resolve with treatment of the substance use and achievement of abstinence or reduction of substance use. The accumulated evidence suggests a number of steps that the clinician can take to make this differential (Table 86-7). These include three essential features to establishing a DSM-IV diagnosis of independent mood disorder, embodied in the PRISM interview (9): (a) establishing the presence of a full DSM-IV syndrome (e.g., major depression, dysthymia, hypomania); (b) establishing that each of the component criteria that make up the diagnosis exceeds the symptomatology that might be expected from the substances the patient is taking (e.g., insomnia in a stimulant user); (c) establishing the relative ages of onset and offset of mood disorder episodes in relation to periods of active substance abuse, to determine whether the mood syndrome (including past episodes) precedes the onset of substance abuse or has persisted during abstinent periods, and several associated features that may be helpful in building the case for an independent disorder in difficult differentials; (d) probing for a history of serious suicide attempts (56); (e) probing for a history of co-occurring anxiety disorders (57); (f) probing the developmental history for early-onset anxiety disorders or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; (g) probing the family history for mood, anxiety disorders, or other non-substance Axis I disorders (56,58); and (h) documenting response to past treatment efforts, including psychosocial/ behavioral or medication treatments for substance use and for depression, as this data may guide treatment planning going forward. A thorough clinical history, covering each of these areas, provides a strong basis for determining the presence of an independent mood disorder in substance-dependent patients. The PRISM interview has now been computerized (http://www.columbia.edu/~dsh2/prism) and may be used as a clinical diagnostic instrument or a way for clinicians to gain experience with the history taking needed to evaluate DSM-IV mood disorders among substance-dependent patients.

TABLE 86-7 SUMMARY OF DIAGNOSTIC AND HISTORICAL FEATURES USEFUL IN MAKING THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF DSM-IV INDEPENDENT MOOD DISORDER (AS OPPOSED TO SUBSTANCE-INDUCED MOOD DISORDER)

The DSM-IV category of substance-induced mood disorder is an important advance for the field, allowing clinicians to recognize mood disorder syndromes that cannot be established to be independent but seem to exceed the usual effects of substances. However, more research is needed on this category to establish more detailed diagnostic criteria. Current evidence suggests that when relatively rigorous criteria are erected (e.g., requiring that a full major depressive syndrome be met, which each symptom exceeding the expected effects of concurrent substances, as in the PRISM interview (9)), many of the cases so identified as substance induced will subsequently persist during an abstinent period and be reclassified as independent (18,48). Experienced clinicians are able to judge depressions that are substance induced and likely to resolve with abstinence (51). However, resolution with abstinence does not mean that the substance-induced mood syndrome is without prognostic significance, having been associated, for example, with risk of suicidal behavior (49,51) and failure of substance use disorders to remit after treatment (34).

MANAGEMENT OF CO-OCCURRING MOOD AND SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

Depressive Disorders

Antidepressant Medication

Effect on Outcome of Depression

Antidepressant medication has been the most thoroughly studied treatment modality for co-occurring mood and substance use disorders with numerous placebo-controlled trials in the literature. Two meta-analyses (59,60) reached similar conclusions that antidepressant medication is more effective than placebo in improving outcome among alcohol-dependent patients with depressive disorders, with the evidence less clear among cocaine- or opioid- dependent patients (the latter may be due to fewer high-quality studies, as some studies found positive results and others not). Nunes and Levin (59) identified 14 placebo-controlled trials that selected patients with depressive disorders (major depression or dysthymia) co-occurring with alcohol, cocaine, or opioid dependence and conducted an in-depth analysis of depression outcome, substance use outcome, and moderators of medication effects. The effect size (Cohen’s d; standardized difference between means of HDS score at outcome between medication and placebo groups) for the effect of medication on depression outcome was 0.38 (95% confidence interval 0.18 to 0.58), a small- to medium-sized effect that is in the same range and that observed in clinical trials of medications for treatment of routine outpatient depression (61). The magnitude of the effect size was strongly related to placebo response—the greater the placebo response, the smaller the effect of medication.

Effects of Antidepressant Medication on Substance Use Outcome

In the Nunes and Levin meta-analysis (59), among studies that showed medium to large effect sizes of antidepressant medication in improving depression outcome (Cohen’s d >0.5 standard deviations) (62–67), an effect size in the medium range was also observed on outcome measures of self-reported quantity of substance use (59), whereas among studies with smaller effects on depression outcome, the effect size for self-reported substance use outcome was near zero (68–75). Categorical outcome measures reflecting criteria for remission or substantial improvement in substance use showed significant but smaller superiority of medication over placebo and overall modest rates of remission. This suggests the conclusion that treatment of a co-occurring depression with antidepressant medication is helpful in reducing substance abuse when the depression improves, but it is not a stand-alone treatment and cannot be expected to resolve substance problems by itself; concurrent treatment for the substance use disorder (counseling or medication) is also important.

Torrens et al. (60) cast a wider net in their meta-analysis and analyzed placebo-controlled trials of antidepressant medications for substance use disorders, dividing studies into those which did, or did not, require co-occurring depression and focusing on substance use outcomes. They found a significant favorable effect of antidepressant medication among alcohol-dependent patients with depressive disorders, with equivocal findings for cocaine- or opioid-dependent patients with depression, although they conclude that further research in each of these populations is needed.

Results of Recent Trials

Placebo-controlled trials of antidepressants published since these meta-analyses have produced a similar pattern of results, as have more recent meta-analyses (76,77). Several negative trials have been published that had high placebo response (e.g., 78–80), while several studies with low to moderate placebo response showed some evidence of beneficial effects, at least on depression outcome (81–83).

Association Between Mood Outcome and Substance Use Outcome

In addition to the finding that beneficial effects of medication on substance use outcome were observed in trials that demonstrated larger effects of medication on mood outcome (59), some trials also reported the correlation between mood improvement and substance use improvement within the trial dataset. In these analyses, the relationship between improvement in mood and improvement in substance use outcome is consistently strong and positive (66,69,75,82). One study was able to show clearly that mood improvement mediates the effect of medication on substance use outcome (66), but most of such trials lack this type of mediational analysis. Taken together, these data suggest that depression and substance use outcomes are, at least in part, causally related, with improvement in mood resulting in improvement in substance use for some patients. However, the direction of causality may run in both directions, such that improvement in substance use drives improvement in mood.

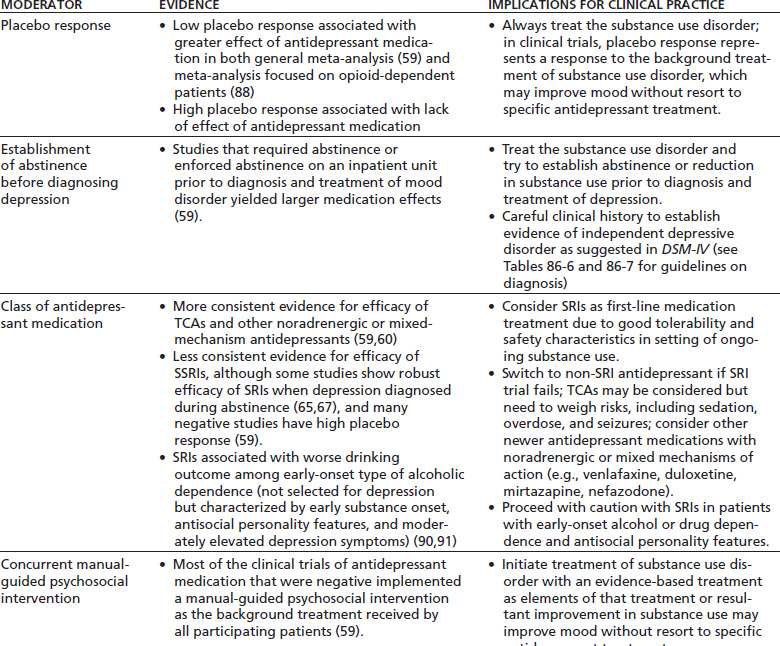

Moderators of Antidepressant Medication Effect

Nunes and Levin (59) in their meta-analysis also studied moderators of medication effect—that is, features of the trials that predicted greater or lesser effect of medication compared to placebo. These bear detailed discussion, because they are useful in developing guidelines for management of patients with co-occurring depression and substance abuse (see Summary in Table 86-8).

TABLE 86-8 FACTORS (MODERATORS) ASSOCIATED WITH EFFICACY OF ANTIDEPRESSANT MEDICATIONS IN CLINICAL TRIALS AMONG PATIENTS WITH CO-OCCURRING DEPRESSION AND SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR CLINICAL PRACTICE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree