88

CHAPTER OUTLINE

■ PREVALENCE OF CO-OCCURRING ADDICTION AND PSYCHOSIS

■ MANAGEMENT OF CO-OCCURRING PSYCHOSIS AND SUBSTANCE ABUSE

The presence of substance use and psychotic symptoms poses special diagnostic and treatment challenges for clinicians in all treatment settings, including mental health, addiction, emergency room, and primary care settings. This chapter focuses on the tasks of assessment, diagnosis, and acute and long-term treatment considerations. The acute management of substance-induced psychosis is discussed in addition to the acute and long-term management of individuals with schizophrenia and addiction. There is a need for comprehensive assessment and integrated treatment that addresses the multiple diagnoses and problems associated with co-occurring addiction and psychosis.

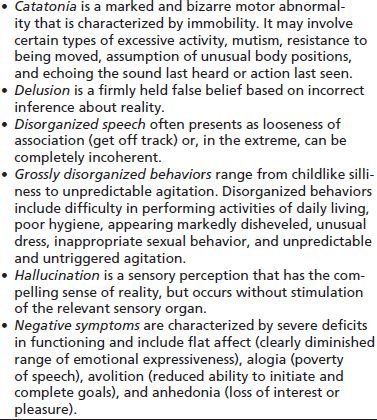

Psychosis is defined as a gross impairment in reality testing that is characterized by severe distortions of perception (as manifested by hallucinations) and severe distortions of thought (as manifested by delusions). Psychosis is a key symptom associated with a variety of diagnoses and states, including schizophrenia, pervasive developmental disorders, dementias, medical disorders, medications, delirium and toxic states, mood disorders, and substance use disorders. According to the current edition of the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV) (1), psychotic symptoms include delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech or behavior, “negative symptoms,” and catatonia (Table 88-1). Hallucinations (e.g., auditory, visual, tactile) and delusions (e.g., paranoid, persecutory, grandiose) are labeled positive symptoms. Negative symptoms greatly impact interpersonal communication and include flat affect, amotivation, poor attention, anhedonia, indifference, and social withdrawal.

TABLE 88-1 PSYCHOTIC SYMPTOMS

PREVALENCE OF CO-OCCURRING ADDICTION AND PSYCHOSIS

Addiction Treatment Populations

Transient substance-induced psychotic symptoms are not uncommon among intoxicated substance abusers; however, addiction treatment programs tend not to include individuals with schizophrenia in longer-term rehabilitation treatment programs. In contrast, mental health treatment settings have recognized that their system must address co-occurring substance use in patients they serve, and they have developed “dual diagnosis” or “co-occurring disorders” treatment programs at all levels of care.

Among patients in addiction treatment settings, a range of severity of psychotic symptoms can occur for vulnerable individuals with many substances—including alcohol, cocaine, amphetamine, club drugs, and marijuana. In the addiction treatment setting, the differential diagnosis most often is determined after a period of abstinence, which can vary from hours to months, depending on the drug involved or the duration of use. One diagnostic criterion used by researchers and clinicians is that psychotic symptoms need to persist for at least 1 month after cessation of substance use in order to be able to make the diagnosis of a primary psychotic disorder comorbid with substance use (2,3). Although psychotic symptoms may persist even after cessation, only 1% to 15% of individuals with a substance-induced psychosis still present symptoms beyond 1 month of abstinence (4). Delayed symptom clearance may be attributed to factors such as the type of substance, neuroadaptive responses to prolonged use, existing psychiatric predispositions, and co-occurring substance use. Patients who develop methamphetamine psychosis, for example, may experience persistent psychotic symptoms and still require hospitalization, despite months of abstinence (5). Evidence suggests that chronic amphetamine use can result in long-term neurobiologic changes, which may persist even after prolonged abstinence and present as a protracted psychosis that is phenomenologically similar to schizophrenia (6,7). A study of cocaine-induced psychosis by Satel and Lieberman (8) suggested that a psychosis persisting for more than several days is likely to be the product of an underlying psychotic disorder.

Psychiatric Treatment Populations

The Epidemiologic Catchment Area community-based study did report rates of co-occurring addiction and schizophrenia and found that 47% of persons with schizophrenia have a lifetime experience of substance use disorders, including 34% who have an alcohol use disorder and 28% who have a drug use disorder, including 16% abusing cocaine. Their odds of carrying a substance use disorder diagnosis are 4.6 higher than those of general population (2,9). Of note, about 70% and 90% of patients with schizophrenia are nicotine dependent, and nicotine is not routinely included in reported rates of substance use disorders, making the actual numbers even higher (10–12). Mental health treatment settings report rates of current non–nicotine-dependence substance use disorders in the population of individuals with schizophrenia in the range from 25% to 75%. However, these epidemiologic data represent a “best guess” as to the true rate of comorbidity, given the challenges of diagnosing substance abuse in the presence of schizophrenia and the problems of diagnosing schizophrenia in the context of a substance use disorder. A Canadian study has shown that of 203 patients with first episode of psychosis, more than half (52%) presented with a comorbid substance use disorder, most often alcohol or cannabis (13). A British survey of 123 patients with first episode of psychosis found that the frequency of substance use is twice that of general population and more common in men, with cannabis being the most frequently used drug (51%), followed by alcohol (43%).

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)-funded Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) study is the largest and longest trial to date examining the effectiveness of several antipsychotic medications in patients with chronic schizophrenia in real-world settings (14). This prospective study was conducted across 57 US clinical sites and included 1,460 individuals with DSM-IV schizophrenia. The patterns of substance use within the study sample, as well as their associations with other baseline, have been previously reported. Within the sample at baseline, 60% was found to use at least one “substance of abuse” (illicit substances and alcohol), including 37% with evidence of a substance use disorder (15). When compared with nonusers, users (with or without a diagnosed substance use disorder) were more likely to be male, African American, less educated, and recently homeless. Furthermore, they were more likely to report childhood conduct problems, a history of major depression, and to have suffered a recent exacerbation of schizophrenia. Interestingly, substance use (with or without a diagnosed substance use disorder) was generally associated with higher or equivalent overall psychosocial functioning at baseline compared to abstinence from substance use (16). From the same study, a recent report examined the relationship between severity of illicit substance use at the time of study entry and 18-month longitudinal outcomes. It was found that those with moderate to heavy use of substances had significantly poorer outcomes in the domains of psychosis, depression, and quality of life compared with both mild users and abstainers (17).

Some data suggest that the use of drugs or alcohol can lead to the earlier onset of schizophrenia in an already vulnerable individual (18). Cannabis is linked to an earlier onset of schizophrenia and more severe positive symptoms among individuals with schizophrenia (11–13,19). Substance use is also associated with an increased duration of untreated schizophrenia (20) and noncompliance with treatment once identified (21). In first-episode patients, substance use is also associated with poorer functional response, more frequent relapses, and a greater symptom burden (22). The addition of drugs of abuse often increases and exacerbates psychotic symptoms in psychiatric patients. In this population, ingestion of even relatively small amounts of drug over a short period can result in an exacerbation of psychiatric problems, increased risk of relapse and hospitalization, use of emergency department services, heightened risk of HIV or hepatitis B or C infections, suicidal behavior, loss of housing, or increased vulnerability to exploitation (sexual, physical, or other) within the social environment (12). Perhaps because of this sensitivity to psychoactive substances, individuals with schizophrenia appear to progress quickly from substance use to dependence, and some researchers suggest that even small amounts of use are problematic and should be viewed as abuse (23). Medication nonadherence and substance use were found to negatively impact community survival in a study among Australian patients with psychosis (11). Substance use has also been associated with emergence of medication resistance (24), involvement with unsafe sexual practices (25), and poorer prognosis of medical conditions, such as diabetes, in patients with schizophrenia (26).

Nicotine dependence is very common (70% to 90%) and a major cause of increased morbidity and mortality in this population (27). This issue is now receiving more clinical attention; however, it has historically been untreated in mental health settings. Treatment guidelines and research are now available to guide clinical practice, including adding tobacco use and smoking cessation in clinical treatment plans (28–30). Effective strategies to addressing tobacco in mental health and addiction treatment settings require broader system level changes, supportive of and consistent with program missions and patient recovery goals (31,32). Treatment of co-occurring nicotine dependence among individuals with schizophrenia often requires a combination of nicotine-dependence medications and psychosocial treatment approaches, including continuity of care between primary care providers and community tobacco control resources (27). Organizational change strategies have been effective at decreasing tobacco use in addiction and mental health settings and at addressing barriers to integrated care (31,32). With adequate training, mental health clinicians can effectively help smokers with schizophrenia improve their motivation and achieve tobacco abstinence (33). The Learning About Healthy Living (LAHL) treatment manual is available online and has been demonstrated to help individuals with lower motivation to learn more about the risks of ongoing tobacco use, increase motivation to change, increase orientation to wellness, and also decide to try to quit tobacco use (34).

Primary Care or Other Health Care Settings

Drug-induced exacerbation of psychotic disorders and transient substance-induced psychotic symptoms are not uncommon in the emergency room setting; however, these cases are far less common in general primary care practices. Of the limited research for this category, most has occurred in the emergency room setting (35).

An interesting phenomenon has been reported among inmate populations where some individuals feign psychotic symptoms in order to obtain quetiapine, a sedative atypical antipsychotic drug (36). Another drug reputed to be nonabusable—bupropion (an antidepressant with dual serotoninergic and dopaminergic effects)—has been reported to be abused in the pursuit of an amphetamine-like high (37).

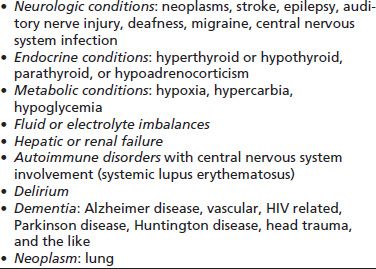

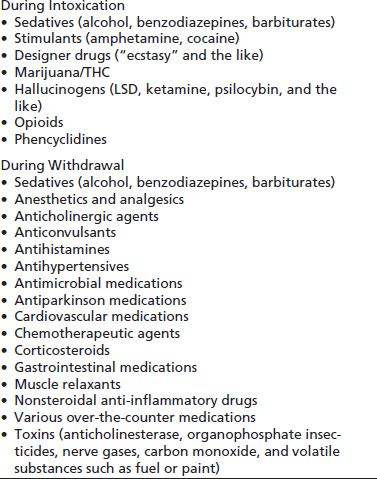

A new patient presenting with both psychotic symptoms and active substance abuse can be a diagnostic dilemma, and the differential diagnosis must be broad. In evaluating psychotic symptoms, clinicians must consider the possibility that these symptoms are caused by a general medical condition (Table 88-2) or substance intoxication or withdrawal (Table 88-3). Psychotic symptoms can occur as the presenting symptom or may be part of a more complex syndrome of cognitive disorders, such as delirium or dementia. Psychotic symptoms can occur in the context of other categories of mental disorders, particularly affective disorders. For example, delusions or hallucinations may be a symptom of major depression or the mania phase of bipolar disorder, both disorders with strong association in the substance-disordered population.

TABLE 88-2 PSYCHOSIS SECONDARY TO MEDICAL CONDITIONS

TABLE 88-3 SUBSTANCES THAT CAUSE PSYCHOTIC SYMPTOMS

A differential diagnosis for an individual presenting with psychotic symptoms should consider a wide range of etiologies and disorders, including brief psychotic disorder, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenia, delusional disorder, psychotic disorder secondary to a general medical condition, substance-induced psychotic disorder, and schizotypal personality disorder. At the time this chapter was written, the American Psychiatric Association was transitioning from the DSM-IV to DSM-5. These classified disorders, listed in the “Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders” section, are very similar in both the DSM-IV and DSM-5 editions.

The type and duration of psychotic symptoms are important in making a differential diagnosis. Psychotic symptoms that have a sudden onset and that last no more than 1 month are labeled brief psychotic disorders. If the symptoms have been present for less than 6 months, a diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder can be made. If the symptoms last longer than 6 months and include prominent delusions or hallucinations and result in a deteriorating course, with evidence of impaired social and occupational functioning, a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder should be considered. In making a diagnosis of psychotic disorder, the clinician needs to rule out mood disorder.

In clinical practice, patients are often seen with a mix of symptoms that may not fit neatly into a diagnostic category such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Schizoaffective disorder is diagnosed when symptoms of a psychotic disorder and a mood disorder (depression, mania, or mixed states) occur during the same time period. In contrast to major depression with psychotic features, schizoaffective disorder features a period of psychotic symptoms in the absence of mood disorder symptoms. A delusional disorder is considered when nonbizarre delusions are present; often, symptoms are well circumscribed and can interfere with functioning to a lesser degree.

Two common scenarios can be challenging for clinicians in establishing a diagnosis of schizophrenia or a substance use disorder. In the first scenario, the clinician is evaluating a new patient who presents with both psychotic symptoms and ongoing substance use. Differentiating schizophrenia from a substance-induced psychotic disorder is not an easy task, especially if the physician does not know whether the patient has a history of serious mental illness. In many cases, it is very difficult to establish the exact chronology of the onset of the psychotic symptoms and that of substance use. Therefore, a definitive diagnosis of a psychotic disorder cannot be established, and treatment of the coexisting psychosis and substance abuse must occur simultaneously. In one longitudinal diagnostic study of 165 patients with chronic psychosis and cocaine abuse or dependence, a definitive diagnosis could not be established in 93% of the cases (38). To establish a definitive diagnosis of schizophrenia, the researchers required that a patient meet diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia at some point after 6 weeks of abstinence from psychoactive substances. Patients were interviewed at multiple points over time (using the Structured Clinical Interview and DSM-III-R criteria) (39). Using these strict guidelines, the primary reasons a diagnosis could not be reached were insufficient abstinence (78%), poor memory (24%), or inconsistent reporting (20%) on the part of the patient. A review of hospital records and collateral information addressed the problems of poor memory and inconsistent reporting, leaving insufficient abstinence as the primary barrier to establishing a diagnosis. The researchers’ finding that most patients continued to use substances reflects the difficulty of treating persons in this population and underscores the need to make clinical decisions within the context of diagnostic uncertainty.

In the second scenario, the clinician is reevaluating a known psychiatric patient with schizophrenia, who presents with symptoms of an undiagnosed substance use disorder. The patient may contribute to a misdiagnosis by downplaying or denying his or her substance-related problems or by pointing to other causes of such problems. One study of patients with schizophrenia who presented at hospital emergency departments found that 33% were recent cocaine users, but half of those persons reported no recent use (38). Thus, urine toxicology and alcohol Breathalyzer tests are strongly advised as adjuncts to patients’ self-reports. The clinician should be careful not to dwell exclusively on the amount of substance used, because psychiatric patients suffer more acutely from smaller amounts of a substance than do nonpsychiatric patients.

The long-term treatment of patients with a first episode of psychosis in the context of substance use is further complicated by the fact that the diagnosis of up to one-quarter of such patients changes from psychotic disorder due to use of a psychotomimetic substance to that of a primary psychotic disorder, especially in individuals with more family history of psychotic disorder, poorer premorbid adjustment, and/or less insight into the mental illness (2,40,41). Substance abusers may be poorly compliant in taking their medications, so that a presenting psychotic relapse may be the result of noncompliance of antipsychotic medication treatment.

MANAGEMENT OF CO-OCCURRING PSYCHOSIS AND SUBSTANCE ABUSE

Diagnostic Assessment

At the time of the patient’s initial presentation for treatment, the clinician should have four primary goals: patient safety, staff safety, elicitation of the patient’s history, and formulation of initial impressions that will lead to a set of treatment recommendations about managing agitation and psychotic symptoms and starting detoxification (2). Often, the most appropriate setting for the evaluation of an acutely psychotic patient is a hospital emergency department, although some psychiatric triage settings also are appropriate. Staff members in those settings are trained to treat such patients in an effective and safe manner. If available, an addiction medicine specialist may be asked to participate in the patient evaluation. Patient safety should be addressed by providing a setting in which external stimuli are minimized to ensure the physical safety of the patient and staff members and to provide a modicum of dignity while the workup is under way. Initial assessment of vital signs should be obtained. Variations in pulse rate, blood pressure, and respiratory function are not uncommon in the presentation of many toxic states.

The patient’s mental status should be assessed, with particular attention given to cognitive impairments and fluctuations of mental status. Consideration should be given to the need for protection of the airway and possible establishment of intravenous access. Physical restraints are used less frequently in mental health settings, and there is an increased use of a quiet room to reduce a patient’s level of anxiety and agitated psychotic symptoms. “Chemical restraints,” examples of which include, but are not limited to, benzodiazepines and antipsychotic medications, may be warranted, but should be given only after the primary assessment has taken place, because the sedative effect of these medications may disguise the presenting clinical symptoms.

Included in the primary assessment is the gathering of history from anyone with information about the patient before his or her arrival at the hospital. Family, friends, or landlords may be very helpful in reporting the patient’s psychiatric, medical, and social history. Emergency personnel or police should be questioned for details of the scene at which they first encountered the patient and their observations of the patient during transport. This information can provide significant insights into the possible involvement of psychoactive substances (as indicated, e.g., by a pattern of confusion or a waxing and waning of signs and symptoms).

Initial laboratory information should include a complete blood count, electrolytes, liver enzymes, glucose, blood urea nitrogen, calcium, blood alcohol, and urine analysis with toxicology screen. If the patient lapses into coma, the administration of parenteral thiamine, glucose, magnesium, and naloxone (Narcan) may be appropriate, even before the laboratory results are available. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain is of little help in differentiating between schizophrenia and drug-induced psychosis (42). However, head CT of an acutely psychotic patient should be considered if the blood and urine drug screens are negative and the patient presents first-episode psychosis. One should note, however, that head CT scans are most helpful in cases of skull fractures, subdural or intracranial hematomas, and contusions but will only be positive in 20% to 50% of cases of diffuse axonal injury (43). If the blood and urine evaluation is not diagnostic and the CT scan is negative, lumbar puncture may be warranted, especially for patients without a history of psychiatric disorders and with an acute change of mental status.

The chief challenge in treating co-occurring psychosis and substance use is to provide integrated treatment while addressing the acute intoxication/detoxification symptoms and the psychotic symptoms. Often, the co-occurring disorder treatment also requires a systematic approach to issues that may be of lesser concern in other settings, such as housing, entitlements, rehabilitation, and use of community services. Clinicians who are nonjudgmental, empathic, and hopeful are most helpful to patients in the treatment and recovery processes. Integrated treatment addresses both problems simultaneously, incorporates active outreach and case management efforts, attempts to increase client motivation for abstinence or harm reduction in a patient- centered and empathic (44) manner, integrates mental health and substance abuse approaches, provides broad-based and comprehensive services, and remains flexible in responding to individual needs.

Management of Substance-Induced Psychotic Symptoms

Pharmacotherapy of the acute psychosis induced by substances should be treated symptomatically. The following discussion focuses on the unique relationship of certain psychoactive substances to the development and acute management of psychotic symptoms.

Alcohol and Psychosis

The psychotic symptoms associated with alcohol use generally occur in the withdrawal stage (45,46). These symptoms are based in the still-undefined interplay of chronic alcohol dependence with the gamma-aminobutyric acid type A, N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA), and dopamine receptors (47). Symptoms typically are referred to as alcoholic hallucinosis, that is, auditory and visual hallucinations that occur in a clear sensorium, often while the patient is alert and well oriented. The auditory hallucinations most often are of the threatening or command type. In this condition, individuals can be in an extremely agitated and paranoid state as a result of the hallucinations and physical discomfort they are experiencing. The onset of this hallucinogenic state has been reported to occur from 12 hours to 7 days after the onset of abstinence from long-term alcohol use. However, there have been reports of symptom onset having been delayed by as much as 3 weeks. The most typical time for emergence of symptoms is within 2 days of abstinence (48–50).

Psychotic symptoms, particularly paranoia, may persist for hours to weeks. Some evidence suggests that individuals with symptoms that are prolonged for weeks or months may have a predisposition to a psychotic illness (48). There can be tremendous similarity between this psychotic appearance and schizophrenia. Research data suggest that between 10% and 20% of patients with alcohol-related psychosis may develop a chronic psychotic disorder clinically similar to schizophrenia (51).

Paranoia and agitation often are treated with benzodiazepines in the same way one would treat uncomplicated withdrawal. However, in the severely agitated patient with concurrent hallucinations, antipsychotics may be warranted. Withdrawal has been associated with the development of extrapyramidal symptoms, including dystonia, akathisia, choreoathetosis, and parkinsonism (52–54). Particular attention should be given to the possible development of extrapyramidal symptoms in a patient treated with antipsychotics during acute alcohol withdrawal or in the patient with a primary psychotic illness. Other medical issues that influence the choice of medication in heavy drinkers in alcohol withdrawal are the risk for withdrawal seizures and the possibility of impaired hepatic function that may increase the risk of serious adverse effects. For agitated, psychotic alcoholics, the most appropriate antipsychotic agents are those with low anticholinergic and sedative effect (55).

Alcohol-induced psychotic disorder (DSM-IV-TR, 2000) is a rare but identifiable disorder distinguishable from withdrawal hallucinosis. It is a complication of alcohol abuse/ dependence characterized by delusions and auditory hallucinations. It is most often associated with a history of heavy drinking. Neuroimaging studies have identified abnormalities in multiple regions of the brain associated with this disorder. The prognosis in treating the positive symptoms with antipsychotic medication and abstinence is fair. Treatment of the negative symptoms has proven to be more challenging (44).

Cannabis and Psychosis

In the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study, reported in 1990, the rate of cannabis dependence or abuse in the general population was estimated at a lifetime prevalence of 4.3%, and the comorbid use of cannabis in individuals with schizophrenia was estimated at 6.0% (56). Approximately 12.5% of individuals over the age of 18 who reported lifetime use of marijuana also had a mental health disorder as identified by the 2003 National Household Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). Adults having tried marijuana prior to the age of 12 compared to those that started use after 18 were twice as likely to be classified as having a serious mental illness in the past year. The most frequent effects of marijuana at levels of moderate intoxication are euphoria (57–59), an awareness of alteration in thought processes (59), suspiciousness and paranoid ideation (60,61), alteration in the perception of time (62), a sensation of heightened visual perception (63), and, at higher doses, some auditory and visual hallucinations (60,64–66). These effects have been reproduced in the laboratory and appear to be partially dose dependent. Some evidence suggests that certain users seek the more psychotomimetic effects achieved through chronic high-dose use of marijuana (67) or by use of high-potency cannabis (68). Depending on individual variation, dosage, and route of administration methods, intoxication symptoms can include suspiciousness, memory impairment, confusion, depersonalization, apprehension, hallucinations, and derealization (58,59,69,70). The symptoms are often reported to be transient, although they can recur on repeated administration of the drug (58,71,72).

There is some evidence that chronic use of cannabis is related to the onset of a primary psychotic disorder (58). Cannabis is considered “one of the few potentially modifiable risk factors in schizophrenia” (41) especially in users with subclinical psychotic symptoms, family history of schizophrenia, or recent functional decline. First-time use, large amounts, and route of ingestion (oral more so than smoked) may be factors in the higher incidence of cannabis-related psychosis (73,74). A study that compared psychotic features in a group of men with psychotic symptoms and high urinary levels of cannabis with such features in psychotic individuals without positive cannabis urine samples showed more hypomania, more agitation, less coherent speech, less flattening of affect, and fewer auditory hallucinations in the cannabis group (73,74). Cannabis use often is associated with a more affective type of psychosis (72).

Typically, the psychosis associated with cannabis is acute and of short duration. However, there are case reports of chronic psychosis attributed to cannabis (75). This is a difficult question to answer for a variety of reasons: Is the patient remaining abstinent? What other drugs might the patient have used? Is there predisposing psychopathology? Frequently, the evaluating clinician must decide whether chronic schizophrenia is secondary to the past use of cannabis. Often, this is an issue for both the patient and his or her family. One retrospective study presented evidence showing better premorbid personalities and reduced age of onset in cannabis-using individuals than in the nonusing schizophrenic population (76). Such differences, however, may be secondary to cannabis use, opening the “genetic window” in an already predisposed patient at an earlier age (77,78). There is a near-twofold increase in the odds of developing a psychotic illness in the cannabis-using population (79,80). There is also evidence that patients with recent onset of a psychotic illness have more severe psychotic and disorganized symptoms if consistently using cannabis (81). When observed over a 10-year period, there is evidence that cannabis use is associated with more severe psychotic symptoms (82). This study further indicated that the severity of schizophrenia symptoms and cannabis use were bidirectional predictors of each other with severe schizophrenia being correlated with higher risk of cannabis use (82).

Cocaine and Psychosis

Transient paranoia is a common feature of chronic cocaine intoxication (8,83), appearing in 33% to 50% of patients. Psychotic symptoms associated with cocaine use are almost exclusively seen in the intoxication phase and rarely extend beyond the “crash” phase in the patient who does not have a primary psychotic illness (41). There is epidemiologic evidence that men have a greater propensity toward psychosis than women and that Caucasians are affected more frequently than non-Whites (84). There are multiple indicators that high-dose use of cocaine over time is strongly associated with the onset of psychotic symptoms, especially in younger users (41,84,85). There also is strong evidence that sensitization occurs with chronic administration of cocaine and amphetamines (41,86). This sensitization is associated with the type of psychotic symptoms that can occur with repeated use of the stimulants. The psychotic features appear to occur with repeated exposure at lower doses. Onset of psychotic symptoms has been associated with reduction in individual doses and the desire for treatment (84).

The most frequently reported psychotic symptoms related to cocaine use are paranoid delusions and hallucinations. Auditory hallucinations are the most common and often are associated with paranoid delusions. Visual hallucinations are the next most common, followed by tactile hallucinations (84). Visual hallucinations have been associated with chronic mydriatic pupils and the appearance of geometric shapes. Nearly all of the hallucinations are associated with drug use. Evidence suggests that the character of the psychotic symptoms experienced is associated with the setting in which drugs are ingested (87).

Stereotypic behavior also can be associated with psychosis. Such behavior occasionally continues after the intoxication subsides. A study of the phenomenology of hallucinations points to an orderly progression in the development of hallucinations, from early visual hallucinations to tactile forms (88). The study comports with the observation that there is an orderly progression of the effects of cocaine intoxication, from euphoria to dysphoria and, finally, to psychosis, and that this progression is related to dose, chronicity, and genetic and experiential predisposition (89).

Amphetamines and Psychosis

The first report of psychosis associated with amphetamines was made by Young and Scoville, who, in 1938, reported psychotic behavior in a patient who was under treatment for narcolepsy. Since that time, there have been many observations and studies of this association. Rockwell and Ostwald reviewed psychiatric hospital records in 1968 and found that the most common diagnosis of patients admitted with covert amphetamine use was schizophrenia.

Amphetamine psychosis can progress through three stages of severity. Initially, symptoms can include increased curiosity and repetitive examining, searching, and sorting behaviors. In the second stage, these behaviors are followed by increased paranoia. In the final stage, the paranoia leads to ideas of reference, persecutory delusions, and auditory or visual hallucinations, which are marked by a fearful, panicstricken, agitated, overactive state (86). Amphetamine-induced psychosis can develop over prolonged exposure in association with large amounts of the drug, which are delivered by any route of administration. The strongest correlation has been seen in those individuals who use large amounts by intravenous injection.

A common presentation of the psychotic, amphetamine-intoxicated patient involves paranoia, delusional thinking, and (frequently) hypersexuality. The hallucinatory symptoms may include visual, auditory, olfactory, or tactile sensations. However, the patient’s orientation and memory usually remain intact. Typically, this altered mental state lasts only during the period of intoxication, although there are reports of it persisting for days to weeks.

Treatment should be initiated by providing a safe, secure place for the patient and should reduce external environmental stimuli. Physical restraints should be avoided or used in a time-limited fashion so as not to complicate the presentation with worsening hyperthermia, dehydration rhabdomyolysis, and possible renal failure. One should keep in mind the potential of amphetamines for lowering seizure threshold, inducing hyperpyrexia, and stimulating cardiovascular compromise, particularly in the patient who is using large amounts in a chronic pattern. In such patients, chlorpromazine (Thorazine) should be avoided because of its potential to lower seizure threshold and worsen hyperthermia. Benzodiazepines can be helpful in the treatment of these symptoms. A common initial dose is diazepam (Valium) 10 mg, either intramuscularly or intravenously, which can be titrated to a level that sufficiently sedates the patient. Patients should be closely monitored for respiratory depression. When using benzodiazepines intramuscularly, the clinician should wait at least 1 hour between doses to avoid inadvertent overdose. It is quite common to see dramatic tolerance to benzodiazepine medications in long-term drug users, so a very high dose may be needed to achieve sedation.

The question of how long the psychosis will last and how likely the patient is to develop a long-term psychotic illness as a result of amphetamine use is not clear. Clinical experience suggests that amphetamine psychosis can last for 3 to 6 months in extreme cases of high-dose use. There is little evidence to suggest that these drugs cause schizophrenia. However, there is a potential for long-term affective instability, a moderate to severe anxiety state, and underlying suspiciousness. Long-term use of methamphetamine may be associated with the appearance of cognitive deficits and negative deficits similar to those encountered in chronic schizophrenia and possibly due to methamphetamine neurotoxicity (41).

Hallucinogens and Psychosis

Hallucinogens have a well-documented role, both ceremonial and recreational, in many societies. However, not until the synthesis of lysergic acid diethylamine (LSD) by Hoffman in 1943 was a hallucinogen available in large quantities and adopted widely as a recreational drug. A national survey in the United States in 1990 yielded an estimate that 7.6% of the population older than 12 years had ever used a hallucinogen. This number rose to 8.6% in 1993. The percentage of patients admitted to psychiatric hospitals with a diagnosis of “schizophrenia and paranoid disorders” at first admission was 10.9% in 1970, but rose to 24% by 1979 and has remained around 20% since that time. The increase is specific to the population ages 15 to 34 years and correlates with the increased use of hallucinogens in this age group. This finding provides evidence pointing to hallucinogens as a factor in the development of schizophreniform psychosis.

The primary model for hallucinogens is LSD, an indole-type drug with structural similarities to serotonin. Included in this class of drugs are dimethyltryptamine, psilocybin, and psilocin, among others. LSD crosses the blood–brain barrier readily and has a potent affinity for the 5-HT2A receptor. Its half-life is approximately 100 minutes, and the effects wear off in approximately 6 to 12 hours. Initially, there are autonomic changes, which are associated with the early affective instability seen after administration, as manifested in laughter or fearfulness. The associated alterations in perception occur subsequently and feature hallucinations of all kinds. The most common hallucinations are visual and the least common, auditory. The occurrence of synesthesia—the blending of the senses—is uncommon but not unknown. There often is a loss of the concept of time. Paranoia and aggression can be profound, but the more frequent experience is that of euphoria and security. The setting can have an effect on the experience, and much has been written on proper preparation for the “trip.”

LSD has a large therapeutic index. Thus, the typical emergency visit secondary to use of the drug occurs as a result of anxiety, a concurrent accident, or suicidal behavior. “Talking down” the patient is the most common way to ease his or her anxiety around the psychotic features of LSD and related drugs. The persistently agitated patient may be treated pharmacologically with a benzodiazepine. Antipsychotic medications have also been widely and effectively used to lessen the psychotic-like experience. If neuroleptics are used, haloperidol 1 to 5 mg, or an equivalent dose of high-potency antipsychotic medication, may be appropriate. Monitoring for neuroleptic side effects such as rigidity, akathisia, and tremor is important.

No clear evidence exists that LSD causes a prolonged psychotic-like illness. Attempts at longitudinal studies have yielded insufficient evidence to support this hypothesis. One difficulty in resolving this question is the high rate of adulterants in the formulation of the drugs and the inability to clearly rule out any preexisting psychopathology.

The incidence of the development of schizophrenia after LSD intoxication is not outside parameters one would expect to see in a youthful population. There is evidence that the occurrence of problems after intoxication is greater in those with a preexisting psychiatric illness. The psychiatric diagnosis most commonly associated with post-LSD psychosis is a form of schizoaffective disorder. The appearance of some affective instability—involving a feeling of an altered state of consciousness—and recurrent perceptual disorder, primarily visual, are the most common symptoms seen in patients with associated chronic psychosis. The schizophrenic LSD user has been shown to have an earlier age of onset and better premorbid social functioning than the nondrug-using schizophrenic individual (76,90).

Phencyclidine, Ketamine, Dextromethorphan, and Psychosis

The cyclohexylamine anesthetics phencyclidine (PCP) and ketamine hydrochloride have similar properties. Both result in psychotic-like experiences during intoxication. Evidence suggests that, in the case of PCP, the psychotic-like state can last for prolonged periods beyond the period of intoxication. Soon after PCP was developed in 1957, it was found to be useful in veterinary practice as an anesthetic (19). This finding led to human experimentation and the recognition that administration of the drugs produces a dissociative state. Patients’ eyes remain open and scanning during surgery, yet they appear to be “disconnected” from their environments and unable to feel pain (91,92). More alarming are reports of bizarre hallucinations and behaviors during the postoperative period (92). Consequently, PCP has not been approved for human use.

Ketamine, at a potency 10 to 50 times lower than PCP, has been shown to produce far fewer of these psychotic-like episodes and was released for use as an anesthetic. Interestingly, children do not appear to develop the associated psychotic-like symptoms.

The history of abuse of these drugs began in the mid-1960s. Street use of PCP increased when prospective users learned that smoking the drug, rather than ingesting it, resulted in fewer unpleasant side effects. It was then that PCP began to be smoked in combination with cannabis (93). The incidence of PCP use increased significantly by 1976, when a survey by the National Institute on Drug Abuse found that 13.9% of 18- to 25-year-olds had experience with the drug (94). PCP’s popularity is attributed to the fact that it can be produced inexpensively and thus frequently is added as an adulterant in other substances sold on the street.

PCP and ketamine can be smoked, ingested, snorted, or injected intravenously. The drugs are rapidly absorbed and excreted in the urine. The intoxicating effects last for approximately 4 to 6 hours. The recovery period is highly variable. The behavioral effects of these drugs appear to be mediated by their effect on the excitatory amino acid NMDA subtype of glutamate receptor. The high-affinity binding of PCP and ketamine to the NMDA receptor blocks ion exchange, resulting in noncompetitive antagonism of the NMDA receptor (95).

Early observations of patients treated with PCP noted the similarities to dissociative and schizophrenic disorders (96,97). The clinical appearance is that of altered sensory perception, bizarre and impoverished thought and speech, impaired attention, disrupted memory, and disrupted thought processes in healthy individuals. There also may be protracted psychosis (98).

There is considerable symptom variation, depending on dose. At lower doses (20 to 30 ng/mL), one is likely to observe sedation, mood elevation, irritability, impaired attention and memory mutism, hyperactivity, and stereotypy. As serum levels rise to 30 to 100 ng/mL, mood changes, psychosis, analgesia, paresthesia, and ataxia can occur. These levels are associated with profound paranoia, aggression, and violent behavior. Higher levels (>100 ng/mL) can cause stupor, hyperreflexia, hypertension, seizure, coma, and/or death.

Treatment of the acutely disturbing effects of PCP-like drugs can be achieved with benzodiazepines in doses equivalent to diazepam 10 mg and greater, titrated until the patient is satisfactorily sedated. The patient’s respiratory status should be continually monitored. There may be a dramatic reduction in aggressive behavior and a significant improvement in the psychotic symptoms. Neuroleptics also can be considered for treatment of the psychotic symptoms. Most typically, a high-potency neuroleptic-like haloperidol (1 to 5 mg) is used because of the decreased anticholinergic properties of these drugs. In cases of overdose, the urine may be acidified with ammonium chloride to facilitate urinary excretion. However, metabolic acidosis can result in other problems, including worsening of rhabdomyolysis, and should be considered only in the most extreme cases. The major active metabolite of dextromethorphan, a nonopioid synthetic analog of codeine and common over the counter cough suppressant, is dextrorphan. This compound like phencyclidine and ketamine is a noncompetitive antagonist of NMDA, which can result in abuse, toxicity, and psychosis (99). There is initially a mild stimulatory effect followed by hallucinations and delusions. At doses greater than 7 mg, there are reports of more profound dissociative effects and “out of body” experiences (100–102). Excessive doses have resulted respiratory depression, tachycardia, and hypertension (103). These doses may also result in false-positive urine toxicology immunoassay for phencyclidine (104). Management most often is an attempt at detoxification with activated charcoal and naloxone (there is limited evidence of its efficacy) (105) though observation and symptomatic treatment are often sufficient. Hinsberger et al. (106) reported a case of long-term cognitive impairment associated with the long-term use of dextromethorphan.

MDMA (“Ecstasy”) and Psychosis

3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA or “ecstasy”) is a derivative of methamphetamine, which has a mixed spectrum of effects, including stimulant and hallucinogenic. MDMA increases the release and inhibits the reuptake of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine from presynaptic neurons, as well as decreasing their degradation by inhibiting monoamine oxidase (107).

Users report enhanced empathy, feelings of closeness to others, euphoria, mood elevation, greater tendency to socialize, increased self-esteem, and altered visual perceptions (41). Hallucinations associated with use generally are mild, but can be intense and severe. Deaths have occurred in cases that presented as a syndrome featuring severe hyperthermia, altered mental status, autonomic dysfunction, and dystonia (108). The mechanism is unclear, but, as with a serotonin syndrome, it may be that MDMA can have a direct effect on the thermoregulatory mechanisms that are potentiated by the context of the drug use. For example, MDMA often is used in the setting of dance parties where there is sustained physical activity, high temperatures, and inadequate fluid intake or dehydration.

Concern about the long-term neurotoxicity of MDMA is growing. Long-term users can suffer serotonin neural injury associated with psychiatric presentation of panic attacks, anxiety, depression, flashbacks, psychosis, and memory disturbances (109). Cases of paranoid psychosis indistinguishable from schizophrenia have been associated with chronic use (110). Although older individuals with schizophrenia may be less likely to use MDMA, use of it and other designer drugs, prescription drugs, and substances must be considered and ruled out in patients with new onset of psychosis.

Management of Schizophrenia with Comorbid Substance Use

Pharmacologic Treatment

Antipsychotic medications are an important component of the treatment of psychotic disorders. They are instrumental in reducing the long-term positive symptoms of the illness. Medications should be complemented by psychosocial therapy that engages clients, offers them practical training in interpersonal communication and crisis management, and develops their rehabilitation and recovery skills. The first step in medication management is to consider the best approach to treating the patient’s schizophrenia or chronic psychosis. This should be followed by consideration of the potential interactions between the substances abused and the possible medication choices. In general, clinicians should avoid prescribing medications that cause sedation when treating patients who abuse sedating substances. In addition, clinicians generally should avoid prescribing medications with abuse liability.

Patients who present with active substance abuse, psychotic symptoms, and noncompliance can be difficult to manage as outpatients. Improving medication compliance in an outpatient setting can be enhanced by reducing positive and negative symptoms, providing psychoeducation and social skills training in medication management, using motivational enhancement techniques to improve compliance, and switching the route of administration of the medication from oral dosing to a long-acting injected medication, if patients are unable or refuse to take oral medications.

Over the past decades, newer second-generation atypical antipsychotic medications have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of schizophrenia. Some of these drugs also have been studied for the treatment of substance use (with and without coexisting schizophrenia) (9,12,55,111,112). This class of medication has the benefit of decreasing extrapyramidal side effects, when compared with conventional antipsychotics. In addition to acting on the dopamine system, atypical antipsychotic drugs also bind to the serotonin system, which is thought to play an important role in maintaining addiction via craving. An accumulating body of literature has suggested that atypicals have some effectiveness in reducing use and craving for substances (55).

Clinical judgment based on the individual patient’s situation should guide the choice of which antipsychotic medication is recommended. Some studies have found no difference between conventional and atypical antipsychotics used to treat patients with co-occurring disorders (89), while others have found that the atypical class may have some advantages (9,12,113–118). In some studies, clozapine appears to be more effective than risperidone (9,12,113,114) and olanzapine (114) in reducing alcohol and/or cannabis use and/or craving among patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective. A study by Brunette et al. (119) indicates that clozapine may also prevent relapses in patients with schizophrenia using alcohol, cannabis, or cocaine. Furthermore, risperidone and clozapine appear to reduce the likelihood of relapse for patients addicted to opioids (120). Akerele and Levin in a 14-week trial comparing olanzapine and risperidone in the treatment of patients with concurrent schizophrenia and cocaine/cannabis use showed a similar reduction in positive symptoms and adherence rates. There was a significant reduction in the use of marijuana in the risperidone group compared to those taking olanzapine; however, there was no significant difference in overall effect (121). Risperidone and ziprasidone increased patients’ retention into dual diagnosis treatment compared with olanzapine or conventional antipsychotics (122).

Interactions between Substances and Antipsychotic Medications

Substances can interact with antipsychotic medications and, therefore, affect their efficacy and side effects in schizophrenia treatment. For example, in the CATIE study, illicit substance use was shown to attenuate the apparent superiority of olanzapine over the other antipsychotics based on the primary outcome measure of time to all-cause treatment discontinuation (123). The interactions are both pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic.

By-products of tobacco smoking, particularly the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, are metabolic inducers of the cytochrome P450 1A2 isoenzyme (CYP1A2). Smoking is known to decrease blood levels of haloperidol, fluphenazine and thiothixene, olanzapine, and clozapine (114,124–127). Abstinence from smoking increases blood levels of antipsychotic medications. Smokers usually are prescribed approximately double the dose of conventional antipsychotic medications that is given to nonsmokers (128). There is at least one report of clozapine toxicity and seizure in the context of a quit attempt, presumably related to a sudden increase in serum levels of the drug (129). The effect on metabolism is important in making treatment decisions regarding hospitalized patients whose smoking habits are curbed, as well as the patient who is attempting to quit smoking.

Caffeine, a drug that is more than 90% dependent on CYP1A2 for its metabolism, is widely used in the general population as well as in patients with schizophrenia. Caffeine increases the levels of clozapine and olanzapine through competitive inhibition on CYP1A2 (130).

A recent meta-analysis suggests that patients with schizophrenia and substance use disorders (especially cocaine related) are more likely to experience extrapyramidal adverse effects with antipsychotic medication (131). Substance abuse has been associated with earlier and more severe cases of tardive dyskinesia (132–135). However, other studies concluded that substance abuse had no effect on movement disorders when important covariates were considered (128,136,137).

Additional Medication Decisions

After clinicians have chosen a primary medication treatment option that stabilizes the psychotic symptoms, they can consider the use of additional medication, as necessary, to manage comorbid depression, comorbid substance abuse, or another psychiatric problem. For substance use, medications are chosen for specific purposes, including detoxification, relief of protracted abstinence withdrawal, and agonist maintenance.

Psychosocial Treatment

Individuals with both co-occurring mental health and substance abuse or those with substance-induced psychosis will benefit from both comprehensive psychosocial interventions and pharmacologic treatments (138). This section will, however, focus on those individuals with a co-occurring mental health and substance abuse problem as opposed to individuals with substance-induced psychosis. In both acute and long-term settings, research has demonstrated the importance of developing a positive therapeutic alliance as a cornerstone of psychosocial treatment. Moreover, research suggests that patients are more responsive and often willing to engage in treatment when the therapist consistently acts as a nurturing and nonjudgmental ally (139–145). This is of critical importance for both patients with substance-induced psychosis as well as schizophrenia and addiction.

Beyond the therapeutic alliance, there are a number of core treatment strategies that can improve the lives of individuals with both co-occurring mental health and substance abuse. Carey (146) has suggested a five-step “collaborative, motivational, harm reduction” approach for working with the dually diagnosed patient. This approach includes (147) establishing and developing a working alliance, (13) helping the patient evaluate the cost–benefit ratio of continued substance use (decisional balance in motivational enhancement therapy [MET]), (148) helping the patient develop individual goals, (10) helping the patient build a supportive environment and a lifestyle that is conducive to abstinence, and (11) helping the patient learn to anticipate and cope with crises (146).

Psychosocial treatment requires an awareness of the perceived “self-medication” aspects of why individuals with schizophrenia believe they continue to use substances. Despite the negative consequences associated with substance abuse, some individuals with schizophrenia report that using substances helps them cope with symptoms of their schizophrenia (28,149). While clinicians are likely to hear “self-medication” explanations from their patients, the skilled clinician will listen thoughtfully but understand that the research data supporting the concept are mixed (150). Providers need to understand these stories in order to help individuals develop alternative ways to manage the symptoms they are self-treating with substances. Additionally, counseling can introduce other possible explanations for the individual’s ongoing use, such as treating withdrawal symptoms (not necessarily stress).

Nonetheless, working with the dually diagnosed patient requires that the therapist be a good listener and yet be direct in addressing inconsistencies. For example, if a patient has recent positive cocaine urine samples, yet denies any use during the preceding month, the clinician should be understanding of the initial stage of recovery, but point out the discrepancy. Abstinence may be a goal; however, the poorly motivated individuals may benefit from the use of motivational interviewing to develop intrinsic motivation to stop using substances, and to maintain compliance with psychiatric treatment also is a useful strategy.

Keeping patients engaged requires efforts to treat their schizophrenia and to provide encouragement and other “rewards” for small steps toward reducing substance use. It is important to evaluate outcomes other than total abstinence; for example, the clinician might assess the patient for reduced quantity or frequency of drug use, participation in treatment or other activities, compliance with medications and appointments, progress toward short-term goals, and involvement of family or significant others in treatment.

Ongoing treatment of psychosis and addiction requires integrated treatment that attempts to reduce the likelihood of relapse to substances and noncompliance with medications and promotes recovery and wellness. Clinical experience has shown that some psychiatric patients will continue to simultaneously display psychotic symptoms and to actively abuse substances. If the diagnostic assessment was uncertain and the patient is able to achieve prolonged abstinence, the clinician then can consider withdrawing the medication and initiating a medication-free period. Symptoms that continue in abstinence will require formal treatment. The optimal long-term management for schizophrenia is a combination of antipsychotic treatment, psychosocial treatment, and case management as needed. Long-term psychotherapy should consider a dual recovery therapy approach that integrates the best of mental health and addiction psychotherapy.

Pharmacologic Treatment

For the treatment of alcohol use disorders, the U.S. FDA has approved the use of three adjunctive medications: disulfiram, acamprosate, and naltrexone. The clinical record of disulfiram is mixed, and it has yet to be tested in randomized control trials. The possibility of an alcohol–disulfiram reaction requires that it be given only to patients who comprehend the consequences of alcohol consumption when taking disulfiram. According to some clinicians, administration of disulfiram at high doses (1,000 mg) has produced psychotic symptoms in patients not diagnosed with psychotic disorders. Clinical studies of naltrexone in this population are supportive of their use in this population (151). Naltrexone is a relatively safe medication that can be used with patients who are at risk of relapse to alcohol; no alcohol– naltrexone reaction has been reported. Naltrexone’s most common side effects include headache and nausea. Naltrexone can precipitate opiate withdrawal, so clinicians should carefully assess patients’ use of prescription or illicit opiates and be prepared to manage opiate withdrawal symptoms. Liver function tests should be monitored when using either disulfiram or naltrexone. Disulfiram, a medication used to promote alcohol abstinence, shows some benefits in patients with schizophrenia and an alcohol use disorder (2,9,12,113) but may induce psychotic side effects and requires monitoring of hepatic function (9,12). Roncero et al. (55) caution against the use of disulfiram in patients with history of affective disorders, suicidality, cognitive deterioration, or poor impulse control. Naltrexone, an opioid receptor agonist, reduces drinking days, craving, and overall use of alcohol in dual diagnosis patients (9,12). So far, there are no systematic studies of acamprosate or long-acting injectable naltrexone in patients with schizophrenia and alcohol use disorders.

For cocaine addiction, there are no FDA-approved medications. For individuals with schizophrenia and cocaine addiction, there are numerous small studies that suggest some promise for a range of medications (desipramine, selegiline, mazindol, and amantadine); however, there is no strong evidence that any of these adjunctive medications are effective. The best option may be to provide excellent integrated psychosocial treatment and adjust the primary antipsychotic medication as needed (10,139,152).

Pharmacotherapy for tobacco addiction can include adjunctive FDA-approved medications such as nicotine replacements (transdermal patch, gum, lozenge, spray, or inhaler), bupropion (Zyban), or varenicline (Chantix). Adjunctive smoking cessation medications and specialized smoking cessation programs tailored to this population appear to benefit this population (10,147,153). There is some evidence that bupropion, as an adjunct to antipsychotic medication, may help dual diagnosis patients who want to stop smoking (12,113). However, its potential to reduce the seizure threshold limits its use in presence of an antipsychotic with similar effect, such as clozapine (55). There is some evidence that patients also prescribed atypical antipsychotics will have higher rates of abstinence, lower rates of attrition, and lower levels of expired carbon monoxide compared to those on typical antipsychotics (147). An important finding of these studies was that psychiatric symptoms were not exacerbated in patients who achieved abstinence from cigarettes (147,153,154).

Psychosocial Treatment

Co-occurring disorder treatment programs have used psychosocial interventions in strikingly different ways, but there are many core similarities. Some have favored an active outreach case management approach, whereas others have relied more heavily on MET in the clinical setting (23,50,139,141,155–158). Three specific psychosocial treatments that are commonly used across approaches and fundamental to dual diagnosis treatment are MET (159), relapse prevention (160), and 12-step facilitation (161). However, these three treatment approaches require modification from their original form due to the biologic, cognitive, affective, and interpersonal issues often present among individuals with schizophrenia. These modifications of conventional substance abuse treatments should take into account the common features among individuals with schizophrenia, including lethargy as well as low motivation and self-efficacy, cognitive deficits, and maladaptive interpersonal skills. These psychosocial issues both highlight the need and sometimes difficulty for a strong treatment alliance (134).

For individuals with schizophrenia and substance abuse, the prognosis for long-term improvement and recovery depends on a treatment strategy that addresses both patients’ addiction and their symptoms related to their schizophrenia, that responds to the unique vulnerabilities (cognitive, affective, social, and biologic) of the individual, and that maintains an empathic and collaborative approach.

Training programs should be designed to develop basic dual diagnosis assessment and treatment competencies for all staff members. Clinicians should have skills and knowledge in integrating mental health and addiction treatment approaches, with special emphasis on MET, relapse prevention, and 12-step facilitation for addiction, as well as social skills training and behavioral therapies for psychiatric disorders. Other helpful strategies include behavioral contracting, community reinforcement approaches, social skills training, money management, peer support/counseling, vocational/educational counseling, and family/network therapies.

The 12-step approach has been modified for dually diagnosed individuals, who often have reported some difficulty in engaging in 12-step groups, given the perceived stigma toward individuals with serious mental illnesses and the cultural opposition to use of psychiatric medications. Dual Recovery Anonymous meetings, sometimes called Double Trouble, can provide a bridge to the 12-step movement for patients with dual disorders. Dual Recovery Anonymous meetings are often held in mental health settings or social houses. The groups encourage recovery for both problems and emphasize the importance of taking appropriately prescribed medications. Spiritual health also is a focus of the meetings, including connecting with a higher power, developing a sense of community, and finding meaning and purpose in life. The research has shown that Double Trouble participation has both direct and indirect effects on several important components of recovery, including drug/alcohol abstinence, medication adherence, self-efficacy for recovery, and improved quality of life (162).

Several dual diagnosis treatment approaches with similar behavioral therapy models have been suggested. The Motivation-Based Dual Diagnosis Treatment model employs a stage-matching approach that combines mental health and addiction treatments, based on the patient’s motivational level, severity of illness, and dual diagnosis subtype. The Motivation-Based Dual Diagnosis Treatment approach acknowledges the distinctive features of the schizophrenia– addiction subtype (139). The model uses stages of change in assessing the patient and matches treatment strategies and goals (such as abstinence or harm reduction, medication compliance, session attendance) to the individual’s stage of readiness to change.

MET is a primary psychosocial approach for the patient with poor motivation. However, when the traditional MET approach is used with dually diagnosed patients, clinicians should recognize the need for adjustments, which include the following:

■ The clinician should play a more active role in offering practical, useful solutions to the patient’s concerns about everyday survival. The clinician should not assume that dual diagnosis patients have the personal tools or social resources to solve problems effectively while actively engaged in addictive behaviors.

■ MET should be formulated as a continuing component of treatment rather than being limited to the four sessions that were envisioned for nonschizophrenic substance users.

■ The decision balance intervention, a cornerstone of MET, should be employed so that it fully accounts for the experience of substance use in relation to other and more systemic problems, such as schizophrenia and medication compliance.

■ The clinician should acknowledge that dually diagnosed individuals may not consistently accept the diagnosis of schizophrenia, may vary in their willingness to maintain medication for schizophrenia, and may have greater or lesser motivation to stop their substance use.

Attending to the role of motivation is important to the success of the treatment plan. Clinicians must work to strengthen patients’ motivation while confronting the effects of schizophrenia and stressing the importance of medications in managing the condition. Prochaska et al. (163) defined motivation in relation to a five-stage scale (precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance). Individuals enter treatment at various stages, and, therefore, interventions need to be tailored accordingly; one author recommends using experiential processes (cognitive and emotional learning) for patients in contemplation or preparation stages, switching to behavioral processes (such as contingency management) for those in action or maintenance phase (164). Interventions that address individual stages of change have an impact not only on rates of substance use but also on the severity of psychotic symptoms and on the need for antipsychotics (165). A study that evaluated a group of 295 patients who were diagnosed with both schizophrenia and a substance use disorder concluded that more than half could be described as “low motivated” (i.e., in the precontemplation or contemplation stage), with the degree of motivation related to the substance or number of substances abused (10). Of those patients who abused alcohol, 53% were assessed as having low motivation; the figures for cocaine and marijuana were 65% and 73%, respectively. In another study, a simple five-point Likert scale of current motivation for treatment successfully predicted the dually diagnosed patient’s likelihood of achieving abstinence (144). Studies evaluating the impact of MET-based interventions for substance using patients with psychotic disorders show that substance use is decreased, but the major problem with these studies is the high rate of subject loss to observation (63,166). One study shows that MET-based interventions are more effective for patients who use cocaine, whereas the standard psychiatric interview worked better for patients using cannabis.

Certain conditions can work to accelerate a patient’s motivation to change through use of external motivators, a realization that led to the development of the community reinforcement approach (167). The community reinforcement approach draws on behavioral therapy principles of contingencies, rewards, and consequences. Because external motivation often is lacking among dually diagnosed patients, the community reinforcement approach searches out a range of possible motivators—disability income, probation, family, and so forth—and uses those motivators to engage, support, and monitor patients in treatment.

Treatment must address not only the effects of low motivation but also potential deficiencies in the cognitive skills known as receiving–processing–sending skills, which allow individuals to act on information in a coherent and productive manner (134). These skills assume basic levels of attention, memory, and reality awareness. In individuals with schizophrenia, such levels often are lower than normal, so that the benefits of traditional relapse prevention treatment, which is built on a cognitive learning model, are sharply reduced (160). Thus, the treatment model must be modified and tailored to the dual diagnosis patient, switching the treatment emphasis from cognitive to behavioral approaches as needed.

Traditionally, relapse prevention and 12-step facilitation have been used in addiction settings to help patients with a range of social, interpersonal, and problem-solving skills that lead to self-esteem and self-efficacy (168). Self-efficacy, in particular, is directly related to the change processes that influence maintenance and relapse (61,160,169). Relapse prevention and 12-step programs can help individuals increase their self-efficacy and self-esteem. However, relapse prevention therapy tends to be administered in a cognitive therapy manner, while clinical experience suggests using a more action-oriented behavioral approach, featuring role-playing, modeling, coaching, positive and negative feedback, and homework. Traditional psychiatric approaches of social skills training use this methodology in rehabilitation programs (94,170). The Lieberman modules include psychosis symptom management, medication management, leisure skills, conversation skills, and community reentry. Traditional relapse prevention is easily adapted to work with individuals with schizophrenia with a focus on addressing difficulties in communication and problem solving.

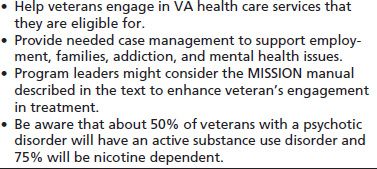

Several other exemplary treatment programs for substance abusers with comorbid psychiatric disorders deserve discussion here. The dual diagnosis treatment program developed at the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Medical Center uses an integrated care model, in which treatment teams provide both mental health and substance abuse services. A relapse prevention module was designed in consideration of the cognitive deficits of persons with schizophrenia spectrum diagnoses. Patients are taught and given an opportunity to practice a series of social skills believed to reduce the incidence and severity of relapse. Assertive case management, including housing and advocacy services, also plays an integral part of the treatment program (Table 88-4). In addition to medications aimed at relief of psychotic symptoms, patients with comorbid alcohol dependence are offered disulfiram. Finally, patients submit to urine drug screens twice per week. A more detailed description of this treatment program is available from Ho et al. (120).

TABLE 88-4 STRATEGIES TO HELP VETERANS AND OTHER ACTIVE DUTY SERVICE MEMBERS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree