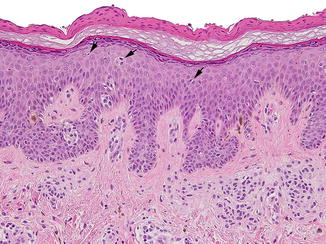

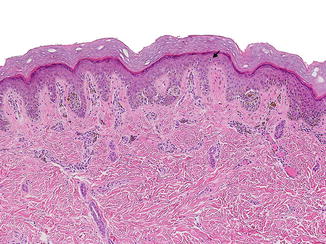

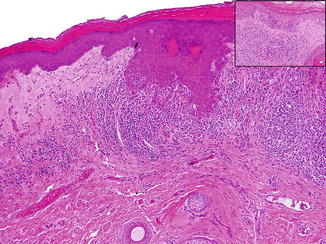

Fig. 3.1

Compound congenital melanocytic nevus: in addition to nests, there is a proliferation of single cells dispersed along the epidermal basal layer, which lack significant cytologic atypia (a). Malignant melanoma arising within a congenital nevus for comparison (b)

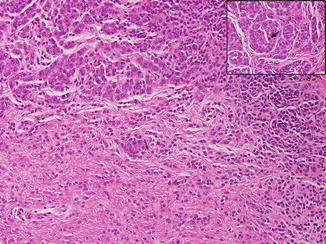

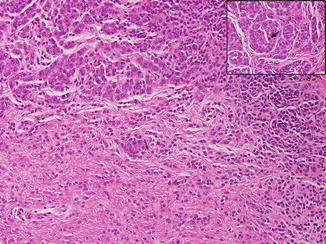

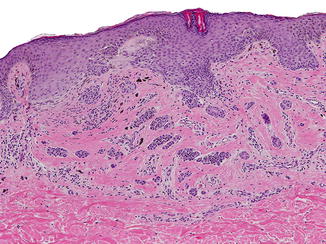

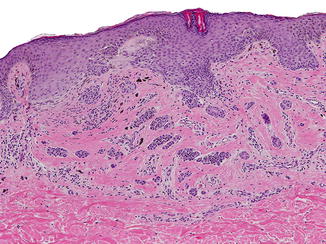

Atypical proliferative nodules of congenital nevi may be misconstrued for melanoma arising within the nevus. These nodules frequently present at birth as part of a congenital nevus, but they can also develop later in life. Typically, they occur in the dermis and are composed of large spindled or epithelioid melanocytes (Fig. 3.2). Moderate to severe cytologic atypia is rarely present. The lesional cells usually blend with the surrounding smaller nevus cells; however, this tendency is not invariable and often raises concern for malignancy. Despite their expansile growth and the cytologic atypia, the majority of these proliferative nodules, especially in the neonatal period, behave in a benign fashion. According to Barnhill, melanoma arising in association with a proliferative nodule histopathologically has not been observed in more than 30 years of consultative practice [5, 6]. Therefore, knowledge of the clinical context is extremely important to avoid overdiagnosis of malignant melanoma developing within a congenital nevus. Features that favor the diagnosis of malignancy include high-grade uniform cellular atypia, atypical mitotic figures, and focal necrosis within the nodule.

Fig. 3.2

Atypical proliferative nodule arising within a congenital nevus: compare the atypical cells within the proliferative nodule with the small basophilic nevus cells dissecting through the collagen bundles. The proliferative nodule is composed of pleomorphic, epithelioid melanocytes demonstrating severe cytologic atypia. Note the central mitotic figure (inset, arrow)

Prepubertal Nevi

Dysplastic nevi usually become clinically apparent at puberty or adolescence and continue to develop throughout life. True dysplastic nevi have been described in prepubertal children [7, 8]. However, melanoma in prepubertal children is rare, with an incidence of 0.8 per million in the first decade of life [9]. The incidence of melanoma is seven times greater in the second decade of life than in younger children, suggesting that prepubertal children differ from older children and adults [10]. In a study by Evans et al., more than half of the originally diagnosed melanomas in a preadolescent group were considered in retrospect by the experts to be benign nevi [11]. This tendency to overdiagnose prepubertal melanomas may stem from the fact that benign nevi as well as Spitz nevi, which are common in children, frequently have atypical microscopic features that mimic melanoma. However, given the rarity of melanoma in young children, that diagnosis should be rendered with extreme caution.

Nevi of Old Age

While most melanocytic lesions can be unequivocally classified as benign nevi or melanoma, a special type of melanocytic proliferation often encountered in the elderly may pose great diagnostic challenges to the pathologist. Lentiginous dysplastic nevus of the elderly was first described in 1991 by Kossard et al. [12], who observed clinically atypical pigmented lesions with histopathologic features conforming to the pathology of a dysplastic nevus with a lentiginous pattern. This nevus is notable for a lentiginous proliferation of single melanocytes and small nests along the basal layer, with irregular rete ridge pattern of the epidermis. Focal confluence of single melanocytes over the suprapapillary plates is present, as is mild cytologic atypia of melanocytes characterized by large, irregular hyperchromatic nuclei. Suprabasal spread is generally not a feature.

The true biologic potential of this lesion remains debatable. Given the similarities with lentiginous melanoma, some authors have suggested that these two conditions are the same entity [13–17]. Others regard this lesion as a precursor of melanoma-in-situ in the elderly [12, 18, 19]. Kossard et al. observed that 28 out of 78 biopsy cases diagnosed histopathologically as lentiginous dysplastic nevi in individuals over 60 years evolved into melanoma-in-situ [12]. The recognition of a subset of “unstable” atypical nevi in chronic sun-damaged skin, particularly from the seventh decade of life, may be of importance, as these lesions appear to differ from the dysplastic nevi described in younger individuals, which occur particularly in the second to fifth decades. In the elderly, the accumulated sun damage and age-related mutations in the skin, as well as impaired local immunity, may create an aberrant lentiginous nevus pathway that is unstable, leading to progressive growth that can potentiate the development of melanoma [14, 17, 18, 20]. In conclusion, the classification of this lesion as benign or malignant should take into account the patient’s age in order to avoid under- or over-treatment and devastating consequences for the patient.

Anatomic Location

A subset of melanocytic nevi shares features with melanoma but are biologically inert and do not appear to portend an increased risk for malignancy transformation to date [21]. These benign nevi with atypical histopathologic features tend to occur on specific anatomic sites and are thus designated “nevi with site-related atypia”. Since melanoma may occur at these same sites, it is important for practicing pathologists to recognize the unique features of “nevi of special sites” and avoid misdiagnosis. The benign clinical features contrast with the alarming histopathologic details and can be useful for the correct assessment of the lesion. Anatomic sites that have been implicated in harboring histopathologically atypical but benign nevi include acral sites, genitalia, breast, scalp, ear, and flexural regions.

Acral Nevi

Acral pigmented lesions occur in 4–9 % of the population and consist of nevi (3.9 %), with a minority of lentigines and melanoma [22, 23]. Most acral nevi are symmetrical and lack cytologic atypia or mitotic figures. A small number display atypical histopathologic features, including confluent lentiginous growth, dyshesive nests, variable degrees of cytologic atypia, and suprabasal spread of melanocytes (Fig. 3.3). The two most worrisome features are lentiginous growth and suprabasal spread. Lentiginous growth is usually confined to the center of the lesion; its presence at the margin of the specimen raises concern for a potential melanoma precursor. Suprabasal spread, which sometimes involves the stratum corneum, can be very prominent in up to 40 % of lesions and is usually limited to the center of the lesion [24, 25]. The acronym MANIAC (melanocytic acral nevus with intraepidermal ascent of cells) has been coined to describe these lesions [26]. Cytologic atypia is generally mild, consisting of occasional enlarged melanocytes with hyperchromatic nuclei. The dermal component, if present, consists of small, banal melanocytes showing maturation of the architectural and cytologic features. Because of the aforementioned histopathologic features, the differential diagnosis includes acral lentiginous melanoma; however, knowledge of the site may help the practicing pathologist accept some degree of atypia and avoid overcalling melanoma. There is scant evidence that acral lesions with one or more of the above atypical histopathologic features connote the same increased risk of patient developing melanoma as true nevi with architectural disorder at other sites.

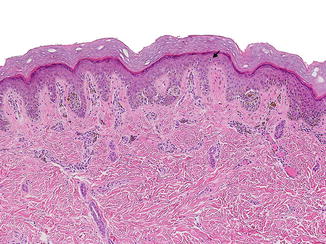

Fig. 3.3

Compound acral nevus: in addition to atypically located junctional nests, this melanocytic nevus also shows a proliferation of single melanocytes along the basal layer. The melanocytes lack significant cytologic atypia. Suprabasal spread of individual melanocytes (arrow), particularly over the center of the lesion, is common and should not be misinterpreted as implying malignancy

Genital Nevi

Pigmented lesions of the vulva are present in 10–20 % of the general population. Benign vulvar nevi occur in only 2 % of females. A subset of them occurs in young, premenopausal women and children, and has atypical histopathologic features [27–29]. Clinically, they present as pigmented, irregular macules or papules measuring up to 1 cm in diameter. Although benign, histopathologically they may be mistaken for melanoma. Vulvar melanoma, however, is rare, accounting for only 3–7 % of melanoma cases [30, 31]. Taking the relative rarity of vulvar melanoma into consideration, the possibility of a benign lesion should be considered first when evaluating genital pigmented lesions, especially in young patients.

The main histopathologic features of genital nevi are prominent, irregular, and dyshesive junctional nests with some degree of cytologic atypia [27–29]. The junctional nests have marked variability in size and shape and are not confined to the tips of the rete ridges as in nevi at most other anatomic sites. Loss of cellular cohesion and confluence of the nests is present. Suprabasal spread may be noted, but is not a characteristic feature. Many lesions show moderate to severe cytologic atypia. Dermal fibroplasia is prominent. Rare dermal mitotic figures have been observed and cannot be relied upon for distinction from melanoma [28, 29]. When examining nevi from the genital region, the above atypical features may be attributed to the anatomic location and should not be considered diagnostic of melanoma. Distinguishing nevi from melanoma in this region is important to avoid radical and unnecessary disfiguring surgeries for the patient.

Nevi of Special Site (Breast, Scalp, Ear, Flexural Regions)

There has been a recent increase in the number of publications describing atypical melanocytic nevi specific to anatomic sites [32–36]. These sites include the breast, scalp, ear, and flexural regions. Recently, Ronglioletti et al. compared the prevalence of atypical histopathologic features of 101 breast nevi to 97 nevi of the torso and extremities [32]. These authors showed that breast nevi exhibited significantly more atypical features than nevi from other sites. Specifically, suprabasal spread, cytologic atypia, and papillary dermal fibroplasia were more frequently encountered. Fabrizi et al. showed similar atypical histopathologic features in 10 % of scalp nevi, especially in adolescents [35]. A large number of auricular nevi show poor lateral circumscription (93 %), cytologic atypia (62 %), and suprabasal spread (57 %) [34, 36]. Finally, nevi from flexural sites, including the axillary folds, the umbilicus, antecubital and popliteal fossae may show asymmetry, poor lateral circumscription, large and dyshesive nests as well as focal lentiginous proliferation (Fig. 3.4). Recognition of site-related atypia is important given the implications of diagnosing melanoma at these sites and performing radical surgeries.

Fig. 3.4

Compound flexural site nevus: peri-umbilical melanocytic nevus showing prominent bridging of the rete ridges and extensive dermal fibrosis

Nevi in Skin Disease

Nevi in Epidermolysis Bullosa

Large acquired melanocytic nevi occur in patients with epidermolysis bullosa (EB) and are referred to as EB nevi. These unconventional nevi occur in all types of hereditary EB, mostly in childhood, at sites of repeated blisters. They are often eruptive and appear as asymmetrical pigmentary lesions with irregular borders and pigment network intermixed with scarred areas. EB nevi may pose a diagnostic challenge because of their clinical and dermoscopic resemblance to melanoma. These alarming clinical features are thought to be a consequence of repeated disruption of the dermal–epidermal junction, fibrosing inflammation, scar formation, and neovascularization [37]. The histopathologic pattern of the EB nevus ranges from the readily recognizable congenital pattern to a worrisome “pseudomelanoma” pattern [38–43]. In the setting of recessive dystrophic EB, histopathologic examination may show features of recurrent nevus (confluent junctional nests, lentiginous growth, suprabasal spread, nests of melanocytes within dermal fibrosis and inflammation). However, despite the alarming clinical appearance and sometimes even alarming histopathologic features, long-term follow-up has confirmed their benign nature. In a recent 20-year prospective study by Bauer et al., there was no incidence of melanoma arising within an EB nevus [39]. The EB nevus should be considered a distinct diagnostic possibility. Knowledge of the EB nevus phenomenon and its histopathologic resemblance to the recurrent nevus should help the practicing pathologist avoid overdiagnosis of melanoma in young patients.

Nevi in Lichen Sclerosus

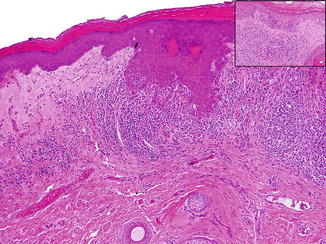

Melanocytic proliferations arising in a region of skin affected by lichen sclerosus are rare and difficult to interpret histopathologically as they share features in common with recurrent nevi and may mimic malignant melanoma. Carlson et al. compared the clinicopathologic features of melanocytic proliferations associated with lichen sclerosus to control benign nevi [44]. Lichen sclerosus nevi frequently demonstrated a trizonal pattern similar to that of recurrent nevi, characterized by “melanoma-in-situ” pattern overlying dermal fibrosis and an underlying dermal nevus. In addition, features of confluent junctional nests, lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia, focal suprabasal spread as well as nests of melanocytes trapped within dermal sclerosis were present (Fig. 3.5). Cytologically, the melanocytes were slightly larger than those in ordinary nevi and had abundant, pale to dusty gray cytoplasm, with oval, vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli. Given that similar histopathologic features may be seen in malignant melanoma, melanocytic nevi of genital skin affected by lichen sclerosus may present a diagnostic pitfall and be misdiagnosed as melanoma. Nonetheless, key histopathologic features can distinguish lichen sclerosus nevi from malignant melanoma. Melanoma exhibits poorly circumscribed junctional melanocytes that extend past the dermal changes of fibrosis-sclerosis, dermal mitotic figures, and deep HMB-45 expression. Melanoma also lacks the trizonal pattern and/or a dermal melanocytic nevus underlying the sclerosis found in lichen sclerosus nevi. Furthermore, studies have shown that the coexistence of lichen sclerosus and vulvar malignant melanoma is rare [45–51].

Fig. 3.5

Compound melanocytic nevus in a background of lichen sclerosus demonstrating architectural disorder. Note the marked lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia (inset). Courtesy of Angelica Selim, M.D., Dermatopathology, Duke University

Nevi in Pregnancy

The effect of pregnancy on melanocytic lesions remains extremely controversial. Several studies, most of which were based on patients’ observations, have reported pregnancy-related changes to melanocytic nevi, including increase in size and darkening of the lesion, possibly related to the influence of hormones [52–54]. However, a more recent study was unable to confirm these changes [55]. Additionally, only a handful of studies [56, 57] looking at the histopathologic changes in melanocytic nevi in pregnancy existed until recently. The initial studies did not demonstrate any significant histopathologic changes. Chan et al. [58] examined the histopathologic features and Ki-67 proliferation index in dermal nevi excised from pregnant women (n = 16) and nevi from location- and aged-matched control patients (n = 15). This group found that nevi in pregnancy were more likely to have dermal mitotic figures (62.5 % versus 13.3 %) and higher mitotic rates (1.44 versus 0.20/mm2) than control nevi; no atypical mitotic figures were identified. The number of dermal mitotic figures ranged from 0 to 4/mm2 in nevi of pregnancy. In half of the lesions, mitotic figures were present in the deeper aspect of the nevus. The increased number of mitotic figures, especially in the deeper portions of the nevus, may cause potential for misdiagnosis since mitotic figures have long been regarded as a feature concerning for malignancy. An important differential diagnosis of a mitotically active nevus is nevoid melanoma. Nevoid melanoma is known to be a diagnostic pitfall due to its deceptively banal histopathologic appearance, including overall symmetry, circumscription, pseudomaturation, and nevoid morphology of melanocytes. Despite a notable increase in mitotic activity, nevi in pregnancy lack other worrisome atypical features for malignancy, such as asymmetry, pleomorphism, hyperchromatic nuclei, and lack of maturation with depth. Therefore, mitotically active melanocytic lesions should not be overcalled as malignant in the context of pregnancy. However, it is readily apparent how they could be misdiagnosed if the clinical history were omitted. The presence of a lentiginous growth pattern, in conjunction with large, single melanocytes irregularly distributed along the basal layer, has also been described in nevi of pregnancy. While these findings may simulate melanoma-in-situ, in the context of pregnancy, conservative excision and clinical follow-up may be advised. Finally, nevi of pregnancy frequently demonstrate the presence of superficial micronodules of pregnancy (81.3 % versus 26.7 % in banal nevi) [58]. These were recently described as rounded clusters of 3–20 large epithelioid melanocytes with prominent nucleoli, abundant pale eosinophilic cytoplasm, and occasional fine melanosomes. These clusters are distinctive from the deeper, smaller type B and C nevic melanocytes and show consistent immunoreactivity for HMB-45 (anti-gp100). Given such findings, concern for melanoma may rightfully arise if the clinical context is unknown to the practicing pathologist.

Traumatized Nevi

Traumatized melanocytic nevi are usually characterized by changes in the epidermis (parakeratosis, serum crust, ulceration) as well as dermis (fibrosis and melanophages) [59]. Occasionally, they may also display atypical histopathologic features similar to recurrent nevi [59]. Recently, Selim et al. examined the histopathologic features of 92 traumatized nevi [60]. Twenty percent of the lesions demonstrated suprabasal spread of melanocytes limited to the site of trauma, under the areas of parakeratosis (Fig. 3.6), whereas 8 % of the cases had evidence of suprabasal spread away from the traumatized area. Two percent of the lesions showed a single mitotic figure in a dermal melanocyte located adjacent to the site of trauma and mild to moderate cytologic atypia. Severe cytologic atypia, significant suprabasal spread outside of the traumatized area, and dermal mitotic figures were not routinely observed and should be suggestive of malignancy. Adeniran et al. reported two patients with atypical histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings in nevi after cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen [61]. These lesions showed focal suprabasal spread, superficial dermal fibrosis, and paradoxical loss of maturation, both morphologically and with aberrant expression of gp100 (HMB-45) in the dermis, thereby mimicking melanoma. However, the nevus cells outside the regions of trauma did not demonstrate the same features. Laser treatment of nevi has been reported to induce similar changes [62, 63]. Taken together, these data suggest that traumatized nevi may have morphologic and immunohistochemical findings similar to malignant melanoma and can present a diagnostic dilemma. However, such atypical findings limited to the traumatized area are compatible with a benign traumatized nevus.