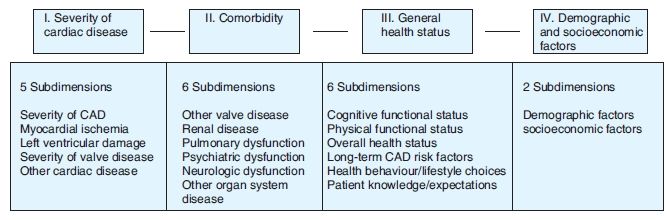

Figure 12.1. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program (CSP #5) ‘Processes, Structures, and Outcomes of Care in Cardiac Surgery’ conceptual model for quality of care.

Within our pluralistic society, the definitions for quality of care have become nearly as variable as the environment in which care is provided, with a renewed focus placed on clinical outcomes assessment. Leaders within the Institute of Medicine, Drs Lohr and Schroeder, defined quality as ‘The degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health care outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge’.49 Depending on the specific research question raised, clinical outcomes should be selected based on pre-established criteria to facilitate patient care, provider, facility, payor, governmental or societal decisions.

Outcomes are most commonly referred to as ‘endpoints’ associated with health care processes. Generally, outcomes represent a change in status from an initial reference time point to a subsequent time point. On the basis of the clinical research question raised, the ideal time period selected for comparison should be based on assessments taken immediately prior to and following the study intervention. To facilitate aggregating clinical science research study findings, a consistent, clear definition of the relevant time period over which to assess outcomes is critically important. By changing the outcomes definition for different time periods, a clinical research study’s findings may be dramatically altered.50

Clinical outcomes may have many attributes, which may aid in the selection process. As a direct measure of the effectiveness of the care provided, the spectrum of a diversity of outcomes may need to be evaluated to reflect changes in patient health status. Health care outcomes have become a prevalent measure used to assess quality, as many of these outcomes may be directly impacted by a given intervention or treatment. To support data-driven decisions for all stakeholders (e.g. patients and their family members, clinical care provider teams, health care facility managers, health insurance leaders, government agency officials and society policy makers), a special emphasis is placed on defining, monitoring and evaluating clinical outcomes of care. This is the first step in the journey of improving the overall quality of health care by means of research-driven empirical findings.

Clinical and translational science research may be differentiated from other fields based upon the research project focus planned on an identifiable intervention. Most commonly, the interventions studied include new diagnostic tests; alternatives for sequencing diagnostic tests; new biomarkers for disease screening or prognosis; new treatments; and/or assessments related to access to care or continuity of care. In addition, clinical research may focus on not only the benefits of these interventions but also on the costs incurred.

As broad-based general categories, these interventions studied may be classified as either diagnostic/prognostic approaches or treatment-based including different therapeutic approaches (e.g. medical therapy, non-interventional procedures and interventional procedures). To be able to optimally identify the effects of treatments, it is important to clarify what was done (e.g. dose, duration and frequency) and how well the care was provided (e.g. the care provider and setting). To be able to assess the quality of the intervention(s) studied, all the detailed processes and structures should be proactively identified for the specific research study question raised.51

Commonly, biomedical or population health interventions rarely are single isolated events, but more often are interconnected inherently with other processes and/or structures of care.52 The range of potential clinical outcomes should be assessed based upon pre-established selection criteria including (but not limited to) the following:

For any given clinical science research question, a multiplicity of outcomes may be considered including (but not limited to) short-term mortality, treatment-related morbidity, health-related quality of life, condition-specific health metrics, patient satisfaction, health plan member satisfaction, utility assessments related to preferences for health states and cost-effectiveness analysis.

In evaluating a clinical or translational science set of outcomes, there are key considerations that should be evaluated. Outcome measures may be unidimensional (e.g. focused on physical functioning) or multidimensional (e.g. include foci on physical, mental and social functioning). Measures may be subjective (including both patient self-report or professional assessments) or objective (e.g. clinical pathology laboratory findings). The outcomes may be focused only on the domains most relevant to the intervention or on more comparisons beyond the study (e.g. to evaluate the generalisability of the current research to other studies). Thus, the choice of outcomes may need to balance internal study goals with external study reality to assure that optimal information is available to drive evidence-based decisions.52

Prospectively, clinical and translational science researchers must identify as to what degree the outcomes should be evaluating both unadjusted and risk-adjusted formats. Data source integrity is critically important. Generally, risk adjustment of outcomes is used to address differences that may be observed in outcomes related to inherent variations in the types of patients treated.53

Defining and uniformly measuring outcomes in a standardised manner is critical to the ultimate success of any clinical research study. Controversies exist as to how to define and to measure the majority of clinical outcomes, even an outcome as simplistic and straightforward as ‘death’. Although the general definition of death relates to absence of biological function, the legal definition for clinical research purposes is based upon the irreversible cessation of all brain activity. Depending on the clinical research question raised, detailed data may need to be collected to verify death occurrence as well as date or time of death. Generally, death rates are reported as a count of deaths as a proportion of the number of cases (of the total number of patients receiving care that may have potentially have died) for a prespecified time period (e.g. 1 year). Other alternative death-related outcomes include time-to-death survival functions, as well as cause of death analyses.

Clearly defining the time period selected for each outcome (e.g. death assessment) following an intervention is extremely important, particularly when evaluating the effectiveness of a procedure or comparing outcomes across providers. Even though a very common clinical outcome is used, such as ‘death’, the challenges of defining and measuring all clinical research study-related endpoints should be carefully considered. In spite of death rates having been used for more than a century as quality of care surrogate markers, the occurrence of death may or may not be an appropriate endpoint for a specific research question.

Risk factors have been documented clinical outcomes, such that the impact of risk is of important consideration. As noted by Donabedian54 ‘quality may be judged based upon improvements in patient status obtained, as compared to those changes reasonably anticipated based on the patient’s severity of illness, presence of comorbidity and the medical services received’. In evaluating clinical outcomes, it is often important to create the ability to compare patient risk subgroups in a way that no unmeasured factor is disproportionately represented (such as an important variable impacting outcome). Blumberg55 noted that patients may be placed at an enhanced risk for an unfavourable event—even if no intervention is initiated. In context of the research study raised, the patient’s profile associated inherently with outcomes may need to be considered for risk-adjustment purposes.

For a clinical or translational science research study, the factor that influences the decision to risk-adjust or not to risk-adjust is to what degree the study’s conclusions might be potentially modified by patient risk characteristics. Different target audiences may require different types of clinical outcome information as data-driven decision-making support, including (but not limited to) the following:

Independent of the health care intervention(s) provided, it may be important to identify for the current research question—to what degree risk factors may influence the outcomes and correspondingly the decision being evaluated.56 Dr Lisa Iezonni further clarifies that the identification of risk factors, and how they are measured and analysed, may be an important consideration for developing medically meaningful and credible risk-adjusted outcome results.57

For the VA CSP #5 ‘PSOCS’ study, an example of a framework for evaluating risk factors appropriate for risk-adjusting a clinical outcomes may be illustrated by the following conceptual model (see Figure 12.2).48

In addition, the dimensions of risk-related to demographic and socio-economic variables may be further stratified by modifiable risk factors (e.g. health behaviour and/or lifestyle choices) and by non-modifiable risk factors (e.g. demographic factors, social status/economic factors and biologic/physiological factors). As a template for consideration, the following factors are commonly evaluated in addition to metrics for the primary disease severity and comorbidities (e.g. other disease states present, which may modify the patient’s health status):

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree