18 Clinical Preventive Services (United States Preventive Services Task Force)

In Chapter 16, we explored how screening is, in the most literal sense, “looking for trouble.” Looking for trouble makes sense if, by finding it early, it can be fixed. But if you don’t know what to do with the trouble you find, you are no longer just looking for trouble, you are asking for it.1 The credibility of preventive medicine depends on the following two goals:

Screening is only done if it meets rigorous standards.

Screening is only done if it meets rigorous standards.

The screening test can realistically be integrated in the busy practice of all clinicians.

The screening test can realistically be integrated in the busy practice of all clinicians.

I United States Preventive Services Task Force

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) was founded in 1984 to address these goals. This chapter focuses on why its work is important and how busy clinicians can keep up-to-date with and incorporate the Task Force’s recommendations. Recommendations for clinical preventive services change frequently with emerging evidence. For more details and updated recommendations, readers should consult USPSTF online (see Website list at end of chapter).

A Mission and History

When the USPSTF was first convened by the U.S. Public Health Service in 1984, it was modeled on an earlier Canadian task force to serve as an independent panel of experts on prevention and evidence-based medicine (EBM). Since 1995, the Task Force has worked under the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). It covers all primary and secondary preventive services, including screening, counseling, and specific chemoprophylaxis.2 The Task Force aims to provide accurate and balanced recommendations across a spectrum of populations, types of services, and disease types. Its mission is to:

1. Assess the benefits and harm of delivering preventive services to asymptomatic individuals (based on age, gender, and risk factors).

2. Recommend which services should be incorporated into primary care.

This mission is very circumscribed. The USPSTF only considers screening of asymptomatic patients, and it only deals with preventive services within primary care. Often, however, USPSTF recommendations are criticized by specialist organizations. Specialists may primarily see preselected patients with subtler symptoms that were missed earlier or may see high-risk groups. Screening decisions for such patients may be different from those for the general population, because the pretest probability of disease is much higher. On the other hand, recommendations of USPSTF are sometimes used for insurance decisions about which screening tests to cover. In these cases, recommendations may be more broadly applied than intended. In contrast to the Community Preventive Services Guide (see Chapter 26), the USPSTF does not take cost-effectiveness or financial concerns into consideration.

B Underlying Assumptions

As outlined in Chapter 16, screening studies are subject to many biases that lead researchers to overestimate benefits. Therefore the Task Force places a higher burden of evidence for benefits than for evidence of harm. For benefits, USPSTF will only accept evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs), community trials, meta-analyses, or systematic reviews. However, it will take into account evidence of cohort studies and case-control studies in calculations of harm.

C Evidence Review and Recommendations

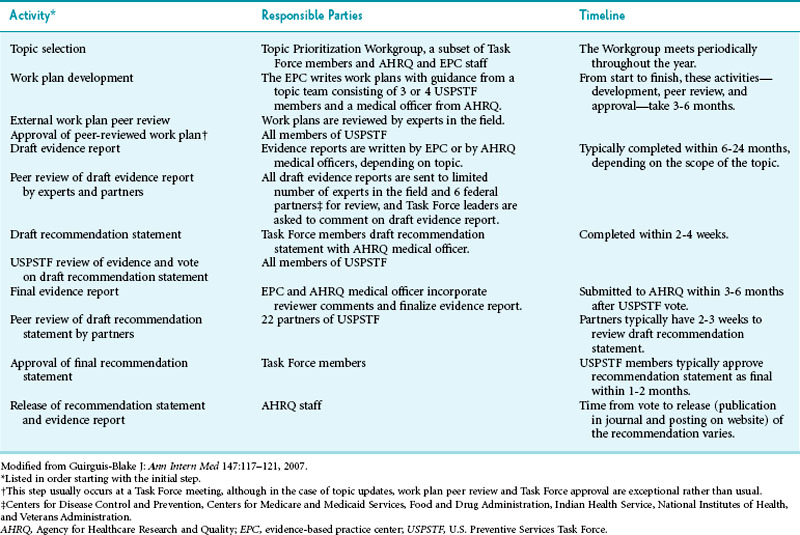

Developing a recommendation is a two-part process: reviewing the evidence and formulating recommendations. Although the Task Force itself makes the recommendations, independent centers review the evidence. USPSTF has established 12 such evidence-based practice centers (EPCs).3 The literature review and recommendation process is highly structured and includes various steps to safeguard the Task Force’s integrity and to help it pursue its goals of transparency, accountability, consistency, and independence4 (Table 18-1). Safeguards include stringent criteria for selection of members, stringent policies regarding conflict of interest, dual review of each abstract, and a comment period for community partners and the public.

Critical Appraisal Questions

Do the studies have the appropriate research design to answer the key questions?

Do the studies have the appropriate research design to answer the key questions?

What is the internal validity?

What is the internal validity?

What is the external validity?

What is the external validity?

How many studies have been conducted that address the key question, and how large are the studies?

How many studies have been conducted that address the key question, and how large are the studies?

How consistent are the results?

How consistent are the results?

Are there additional factors that raise confidence in the results (e.g., dose-response effects, consistency with biologic models)?

Are there additional factors that raise confidence in the results (e.g., dose-response effects, consistency with biologic models)?

Key Questions

1. Does screening for X reduce morbidity and/or mortality?

2. Can a group at high risk for X be identified on clinical grounds?

3. Are accurate screening tests available?

4. Are treatments available that make a difference in intermediate outcomes when the disease is caught early?

5. Are treatments available that make a difference in morbidity and mortality (patient outcomes) when the disease is caught early?

6. How strong is the association between the intermediate outcomes and patient outcomes?

7. What are the harms of the screening test?

Grading Services

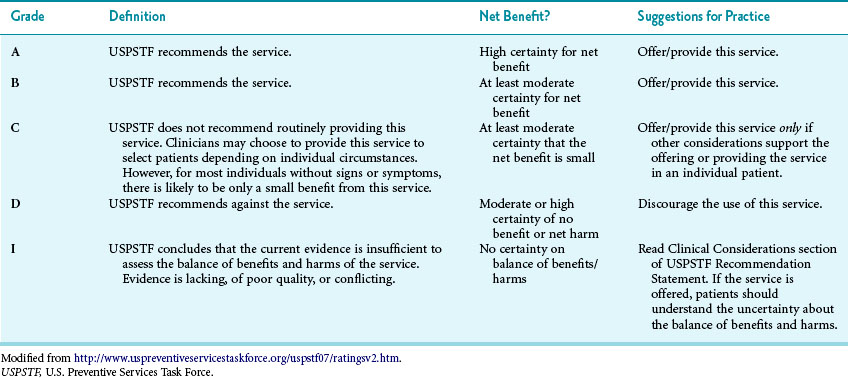

Once Task Force members have answered these questions, the group assigns a grade for the service of A, B, C, D, or I5 (Table 18-2). After assigning a tentative grade, the Task Force discusses these recommendations with federal and primary care partners. Federal partners include the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Health Resource and Services Administration (HRSA), National Institutes of Health (NIH), and Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Examples of primary care partners include the American Medical Association, American College of Physicians, and American College of Preventive Medicine.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree