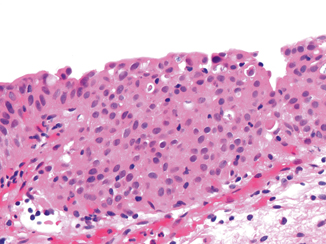

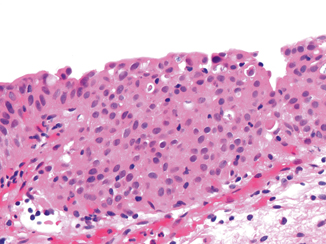

Fig. 13.1

Reactive urothelial atypia (H&E). a and b Reactive urothelial atypia is characterized by mild nuclear enlargement with fine, evenly distributed nuclear chromatin and small pinpoint nucleoli. Intraurothelial inflammatory cells are common

Table 13.1

Distinguishing features for benign reactive changes and urothelial carcinoma in situ

Histologic features | Reactive atypia | CIS |

|---|---|---|

Nucleomegaly | Typically less than 3 × size of lymphocyte | Often greater than 4 × size of lymphocyte |

Nucleoli | Often prominent, but small (pinpoint) | Variable |

Chromatin | Fine, evenly distributed | Variable clumping, coarseness |

Nuclear membrane | Smooth, round | Irregular |

Apoptotic debris | Not typical | May be prominent |

Mitotic activity | May be increased (not atypical) | May be increased (with atypical forms) |

Cytoplasm | Often basophilic | Often eosinophilic |

Nuclear crowding | Not typical | Often present |

Intraurothelial inflammation | Typical | Not common |

Urothelial Atypia of Uncertain Significance

Atypia of uncertain significance is a descriptive diagnostic term that is utilized for flat urothelial atypias that are difficult to classify as definitively reactive or neoplastic. Most commonly, this diagnosis is made when the “severity of the atypia appears out of proportion to the extent of inflammation such that dysplasia cannot be confidently excluded” [1]. The general recommendation for patients diagnosed with urothelial atypias of this indeterminate type is close clinical follow-up care, typically with at least continued urine cytology screening .

Urothelial Dysplasia (Low-Grade Intraurothelial Neoplasia)

Urothelial dysplasia has been a controversial category because of a lack of easily reproducible criteria for diagnosis [5, 6]. The original ISUP 1998 criteria defined urothelial dysplasia as urothelium with “appreciable cytologic and architectural changes felt to be preneoplastic, yet falling short of the diagnostic threshold for transitional cell carcinoma in situ ” [3]. Lesions diagnosed as dysplasia often show a degree of nuclear enlargement that overlaps with reactive atypia, but the loss of cellular polarity is typically more prominent. In addition, although mild, the nuclear chromatin is more hyperchromatic (Fig. 13.2). Nuclear pleomorphism and/or brisk mitotic activity would suggest the diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma in situ over dysplasia. The potential for the over-diagnosis of urothelial dysplasia is significant due to the degree of histologic overlap with benign nonneoplastic urothelial atypias; therefore, the diagnosis of de novo urothelial dysplasia (i.e., with no prior history of urothelial carcinoma) should be made only with great caution.

Fig. 13.2

Urothelial dysplasia (H&E). This urothelium shows marked architectural disorder of the urothelial cells with some mild nuclear enlargement. The cytologic features are not sufficient for diagnosis as carcinoma in situ. This lesion might be classified as urothelial dysplasia (or atypia of uncertain significance cannot exclude flat urothelial neoplasia/dysplasia)

The clinical significance of urothelial dysplasia is not fully known, mainly due to problems with varying diagnostic thresholds being utilized in different studies. Because of these problems, some genitourinary pathologists combine the groups of urothelial dysplasia and urothelial atypia of uncertain significance for reporting purposes. Using this diagnostic approach that combines the two categories, the flat atypias would be reported as urothelial atypia of uncertain significance with a comment regarding the inability to exclude a neoplastic process and a recommendation for continued follow-up, which is the general clinical management strategy for either diagnostic category .

Urothelial Carcinoma In-Situ (CIS)

Urothelial CIS is a neoplastic process that has the potential to progress to invasive urothelial carcinoma . The spectrum of cytologic atypia and the patterns of architectural growth seen in CIS are broad; however, nuclear enlargement is a common feature that is often used as an initial histologic screening evaluation. The nuclei of the neoplastic cells in CIS are often four times or more the size of a lymphocyte. These nuclei may be extremely anaplastic at one end of the spectrum, but have a range to include rather monomorphic nuclear atypia in other examples (Fig. 13.3). The nuclei may be more rounded, and cellular crowding and loss of cellular polarity are common. There may also be nuclear membrane irregularity and the nuclear chromatin in all cases is typically irregularly condensed. Macronucleoli may rarely be present, but this feature is not necessary for diagnosis. It is important to realize that the nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio is not always increased, as many examples of CIS have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. In contrast to prior classification systems that followed a paradigm similar to cervical dysplasia , the ISUP 1998 criteria also clearly stated that CIS “may be present in the entire thickness of the epithelium or only part of it.” Therefore, the presence of any high-grade neoplastic cells, regardless of extent, warrants a diagnosis as CIS. Finally, mitotic figures are commonly identified in CIS, including atypical forms.

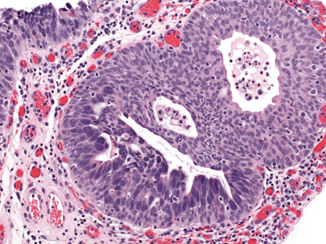

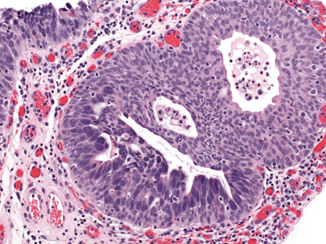

Fig. 13.3

Urothelial carcinoma in situ (H&E). Urothelial carcinoma in situ colonizes a von Brunn nest in the lower left and lines the surface in the upper left of this photomicrograph. The carcinoma in situ cells are markedly enlarged compared to adjacent normal urothelium, and the chromatin is irregular and dark

A number of varying architectural patterns are also described and include pleomorphic, monomorphic, “small” cell, pagetoid, clinging, and undermining (Fig. 13.4a–f) [7]. The pleomorphic pattern of CIS is the prototypical and most easily recognizable type due to its marked nuclear anaplasia. Some examples have more monomorphic nuclei, and the diagnosis is based on more subtle nuclear features such as more homogeneous nucleomegaly, nuclear hyperchromasia, and irregular nuclear contours. “Small” cell CIS has a very high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio due to the presence of minimal cytoplasm; this descriptive term does not imply neuroendocrine differentiation. Pagetoid CIS may be histologically subtle because the neoplastic cells may be few in number. The presence of scattered round cells, which often have a rim of eosinophilic cytoplasm and are histologically distinct from the surrounding urothelium, should alert one to this possibility. Denudation of the urothelium is also common in CIS; therefore, a single layer of “clinging” residual CIS cells may be the only remaining neoplastic component. These clinging CIS cells are markedly enlarged compared to normal basal cells and cytologic atypia may be obvious. Finally, CIS may extend into adjacent urothelium along the basement membrane, lifting up the residual normal urothelial cells in an undermining pattern. To date, there is no known clinical implication for these varying architectural patterns of CIS, and we do not report these individual patterns; however, knowledge of this heterogeneity is useful for diagnostic recognition.

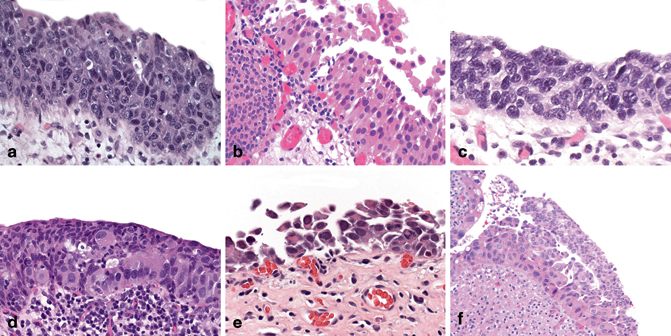

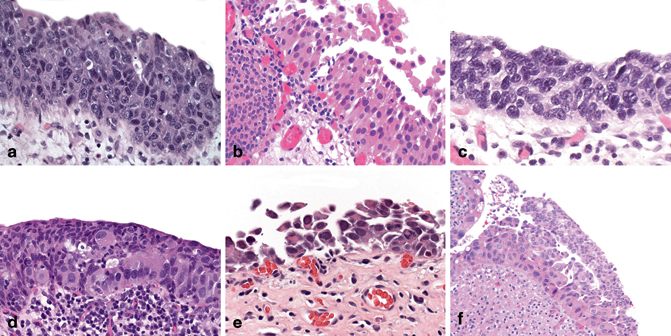

Fig. 13.4

Urothelial carcinoma in situ: architectural patterns. a Pleomorphic. b Nonpleomorphic. c “Small” cell. d Pagetoid. e Clinging/denuding. f Undermining

Immunophenotypic Analysis of Flat Lesions with Atypia

Multiple studies have addressed possible immunophenotypic differences between these types of urothelial atypia [6, 8−17]. Cytokeratin 20 (CK20), CD44 (standard isoform), and p53 are the most frequently utilized immunohistochemical markers in routine practice (Fig. 13.5a–c). In normal urothelium, the umbrella cells express CK 20, while the basal cell layer may express CD44 to a variable extent. P53 expression typically has significant variation between different laboratories because the antibody seems to be susceptible to subtle changes in staining conditions. Despite this variation, benign urothelium should not show diffuse and intense nuclear reactivity. Reactive atypia has similar CK 20 and p53 staining to normal urothelium, but CD44 often shows more diffuse membranous expression in the majority of the urothelial cells and this staining extends into the upper cell layers. CIS, in contrast, shows a loss of CD44 immunoreactivity and full thickness expression of CK 20 in the neoplastic cell population. P53 may show diffuse and intense nuclear relativity in a subset of CIS cases. Other markers that have been suggested as having utility in the classification of flat urothelial lesions include Ki-67, cytokeratin 5/6, and p16.

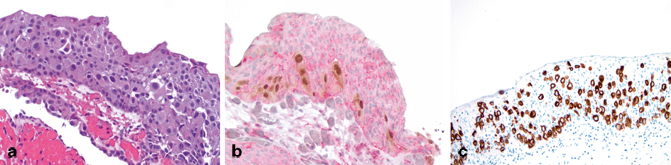

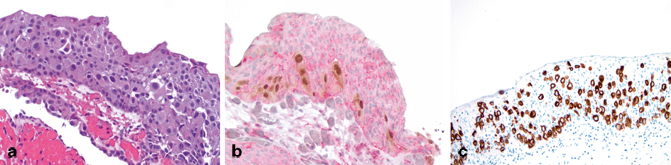

Fig. 13.5

Immunohistochemistry in flat lesions with atypia. a H&E: urothelial carcinoma in situ, pagetoid. b CK20/CD44/p53 cocktail: cytoplasmic CK20 and nuclear p53 reactivity is seen in the pagetoid CIS cell population (both brown chromogen), while cytoplasmic/membranous CD44 is seen in the residual nonneoplastic urothelial cells. c CK20: strong and diffuse CK20 immunoreactivity is present in the CIS cells

The main problem with these immunophenotypic data is that they are based on morphologic classification and are, therefore, often studied only in cases that are easily diagnosed by routine histology . The clinical prognostic significance of specific immunophenotypes in urothelial atypias has not been adequately addressed in the literature. In addition, we anecdotally see cases, typically in an external re-review or consult setting, in which the immunophenotype does not fit the histologic diagnosis. Until more studies address these issues, the classification of flat urothelial lesions with atypia should remain based primarily on routine histologic evaluation.

Diagnostic Comments for Flat Lesions with Atypia

Urothelium may show gradual histologic changes across a broad continuum that includes normal urothelium at one extreme and carcinoma in situ with marked nuclear pleomorphism at the other. The evaluation and classification of flat urothelial atypias across this continuum is one of the most difficult tasks in genitourinary pathology . For clinical management, the most important role of the surgical pathologist is to set a minimum diagnostic threshold for urothelial carcinoma in situ based on nuclear size, chromatin irregularity, nuclear membrane irregularity, and cellular polarity. This threshold should include the monomorphic forms of urothelial carcinoma in situ, which were classified as varying levels of “dysplasia” or “atypia” in previous classification systems. To maintain an appropriate distinction from florid examples of reactive atypia, it is recommended as a general rule that the diagnosis of CIS be very carefully re-considered if the individual nuclei of the lesional cells are less than or equal to the size of three to four lymphocytes.

Papillary Urothelial Neoplasia

Urothelial Papilloma

Under the WHO 2004 classification, very restrictive criteria are employed for the diagnosis of urothelial papilloma [1, 18−20]. “Urothelial papilloma” without qualifiers refers to the exophytic variant of papilloma, defined as a discrete papillary growth with a central fibrovascular core lined by urothelium of normal thickness and normal cytology . The low-power papillary architecture is a relatively simple branching pattern without irregular fusion between adjacent papillae (Fig. 13.6a–c). The umbrella cell layer is often prominent and may show prominent vacuolization, nuclear enlargement, or cytoplasmic eosinophilia. Some unusual features that have been reported in urothelial papillomas include dilation of lymphatic spaces within the papillae, gland-in-gland patterns, and foamy histiocytes within the papillae. This is a rare, benign condition typically occurring as a small, isolated growth that is commonly, but not exclusively seen in younger patients.

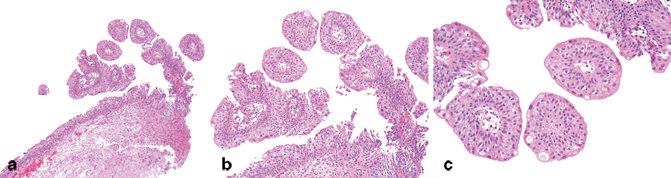

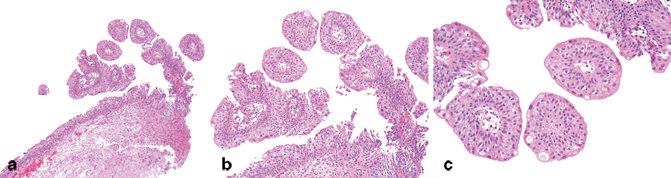

Fig. 13.6

Urothelial papilloma (H&E). a Urothelial papilloma typically has a very simple papillary architecture with significant anastomosis between papillae. b The urothelium should be evaluated in foci that are not cut tangentially. The urothelium appears relatively normal with retained polarity of the cells perpendicular to the basement membrane. c On high-power magnification, the cytology of the urothelial cells is normal. A prominent umbrella cell layer with some vacuolization is also a common feature of papilloma

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree