Patient Story

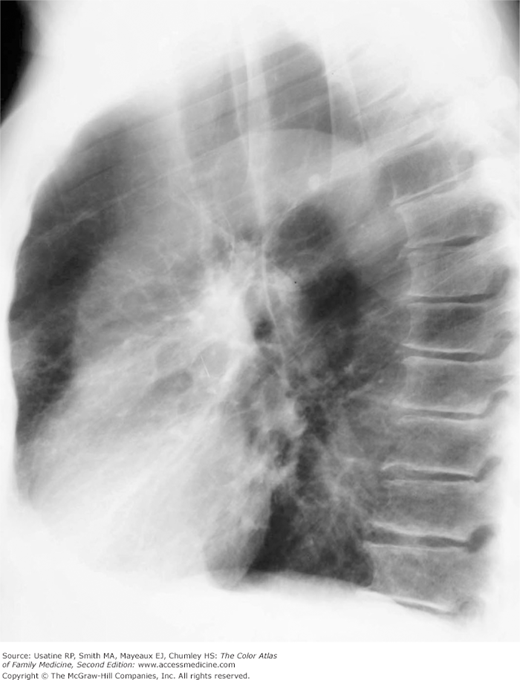

A 74-year-old woman and longtime smoker presents with fatigue and shortness of breath. She has not seen a physician for many years and says she has been basically healthy. On physical examination, she is found to be pale, mildly cachectic, and her lips are cyanotic. Her breath sounds are distant, although crackles can be heard in both lung bases. Her heart sounds are best heard in the epigastrium; a third heart sound is present. She has mild peripheral edema. Her resting pulse oximetry is 74%. Her chest X-ray (CXR) shows emphysema (Figure 56-1) and her echocardiogram confirms heart failure.

Introduction

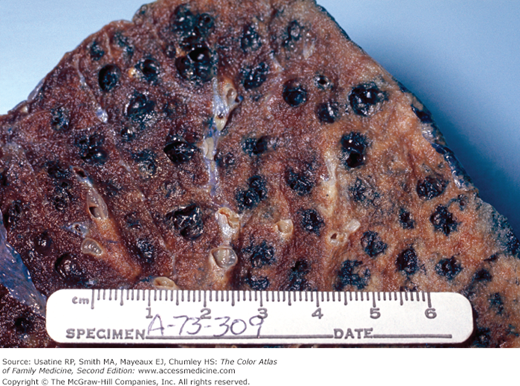

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is defined as a disease state characterized by airflow limitation that is usually progressive and associated with an abnormal inflammatory response of the lung to noxious particles or gases.1 COPD is preventable and treatable. Some patients have significant extrapulmonary effects (particularly cardiac) that may contribute to disease severity. Worldwide, tobacco smoke is the primary cause of COPD (Figure 56-2).

Epidemiology

- Estimated prevalence of COPD in adults older than age 18 years in the United States (2008) is about 13.2 million cases, or 4% of the population (95% confidence interval [CI], 3.8 to 4.1).2

- Fourth leading cause of death both in United States and worldwide. Mortality rates have declined for men from 1999 to 2006 (57 per 100,000 to 46.4 per 100,000) and remained fairly stable for women (35.3 per 100,000 to 34.2 per 100,000).3

- In a study in Latin America, prevalence rates ranged from 7.8% to 19.7% of the population;4 a prevalence of between 3% and 11% has been reported in never-smokers.1 This high rate among never-smokers is most likely related to indoor cooking with open wood fires.

- In a Swedish study of COPD (birth cohorts from 1919 to 1950), the 10-year cumulative incidence rate of COPD was 13.5% using Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteria (Table 56-1) based on 1109 patients with baseline respiratory symptoms (76.6% of the original symptomatic cohort and 16.7% of the total cohort).5

- Estimated direct costs associated with COPD in the United States are more than $29 billion with additional indirect costs of $20.4 billion.1

Grade | FEV1/FVC | FEV1 |

|---|---|---|

Mild COPD (GOLD 1) | <0.7 | ≥80% predicted |

Moderate COPD (GOLD 2) | <0.7 | <80% but ≥50% predicted |

Severe COPD (GOLD 3) | <0.7 | <50% but ≥30% predicted |

Very severe COPD (GOLD 4) | <0.7 | <30% predicted or FEV1 <50% with respiratory failure or right-sided heart failure |

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Mediated by chronic inflammatory responses to environmental factors, especially cigarette smoke, that results in recruitment of inflammatory cells in terminal airspaces and release of elastolytic proteinases that damage the extracellular lung matrix and cause ineffective repair of elastin and other matrix components.

- Oxidative stress may be an important amplifying mechanism in COPD development and exacerbations.1 In addition, there appears to be an imbalance between proteases and antiproteases in the lungs of patients with COPD.

- The inflammatory process leads to obstruction and later fibrosis of small airways and the destruction of lung parenchyma. Circulating inflammatory mediators may contribute to muscle wasting and cachexia and worsen comorbidities such as heart failure and diabetes.1

- Gas exchange abnormalities result in hypoxemia and hypercapnia.

- Pulmonary hypertension may occur as a result of hypoxic vasoconstriction of small pulmonary arteries.

- Genetic mutations (e.g., α1-antitrypsin deficiency [1% to 2% of cases; affects 1 in 2000 to 5000 individuals]) are present in some patients. Suspect a genetic mutation when emphysema is found in a patient age 45 to 50 years or younger, a positive family history of COPD, primarily basilar disease, or a minimal smoking history.6 Single-nucleotide polymorphisms at three loci—TNS1, GSTCD, and HTR4—are associated with COPD, as is genetic variation in the transcription factor SOX5.7,8

Risk Factors

- Smoking (direct and passive)—COPD relative risk (RR) for ever smoking is 2.89 (95% CI, 2.63 to 3.17) and RR for current smoking is 3.51 (95% CI, 3.08 to 3.99).9

- Airway hypersensitivity (15% of the population attributable risk).1

- Occupational exposures (e.g., gold and coal mining, cotton textile dust).1,2,6 The estimated fraction of COPD symptoms or functional impairment attributed to these exposures is 10% to 20%.1

- Indoor air pollution from burning wood and other biomass fuels, particularly with open fires, poorly functioning stoves, and poorly ventilated dwellings.1

- Reduced maximal attained lung function (e.g., preterm vs. full-term infants).1

- Infections (e.g., early childhood infection, chronic bronchitis, HIV, tuberculosis).1

- Poverty.

- Parental history of COPD (odds ratio [OR] 1.73).10

- α1-antitrypsine deficiency (genetic disorder).

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of COPD should be considered in a patient older than age 40 years with dyspnea (persistent or progressive or worse with exercise), chronic cough (even if intermittent or nonproductive) and/or sputum production, and/or a history of COPD risk factors including a family history of COPD.1

- COPD’s three most common symptoms are cough, sputum production, and exertional dyspnea. In one study of newly diagnosed patients, most presented with cough (85%) and exertional dyspnea (70%); almost half (45%) reported increased sputum production.11 Most patients were classified in GOLD stage 0 to 1 (42%) or 2 (46%) (see Table 56-1).

- Patients may also report chest tightness, often following exertion; fatigue, weight loss, and anorexia are symptoms later in the disease.

- Several validated questionnaires are available to assess symptoms in patients with COPD; GOLD recommends the Modified British Medical Research Council (MMRC) questionnaire (Box 56-1) or the 8-question COPD Assessment Test (CAT; http://catestonline.org).1

- Physical findings may include:

- Tobacco odor and nicotine staining of fingernails.

- Increased expiratory phase or expiratory wheezing.

- Signs of hyperinflation—Barrel chest, poor diaphragmatic excursion.

- Use of accessory muscles of respiration—Intercostals, sternocleidomastoid, and scalene muscles.

- Late in illness—Cyanosis of the lips and nail beds, wasting, and cor pulmonale (right-sided heart failure—signs include increased jugular-venous distention, right ventricular heave, third heart sound, ascites, and peripheral edema).

- Tobacco odor and nicotine staining of fingernails.

0 – Not troubled with breathlessness except with strenuous exercise. |

1 – Troubled by shortness of breath when hurrying on the level or walking up a slight hill. |

2 – Walks slower than people of the same age on the level because of breathlessness or has to stop for breath when walking at own pace on the level. |

3 – Stops for breath after walking about 100 yards or after a few minutes on the level. |

4 – Too breathless to leave the house or breathless when dressing or undressing. |

Postbronchodilator spirometry secures the diagnosis and provides the severity classification:1,12 SOR B

- At risk—Chronic cough and sputum production with normal spirometry.

Additional tests that may be useful in management are sputum culture (in acute exacerbations to assist in confirming pneumonia), complete blood count (to identify anemia or polycythemia), and blood gases (confirms hypoxia when peripheral oxygen saturation is <92% or respiratory failure [PCO2 >45]).1,13

- A serum level of α1-antitrypsin should be measured if you suspect a genetic mutation (young age at presentation [≤45 years], lower lobe emphysema, family history, minimal smoking history).

- Exercise (walking) tests to assess disability or response to rehabilitation.1

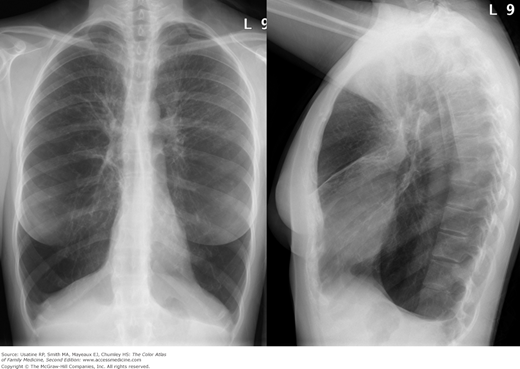

A CXR is not useful for diagnosis but is helpful for excluding other diseases or identifying comorbidity (e.g., heart failure). Findings on CXR include:3

- Hyperinflation manifested by the following (Figures 56-1, 56-2, 56-3):

- Increased anteroposterior (AP) diameter.

- Increased retrosternal air space.

- Infracardiac air.

- Low-set flattened diaphragms (best assessed in lateral chest).

- Vertical heart.

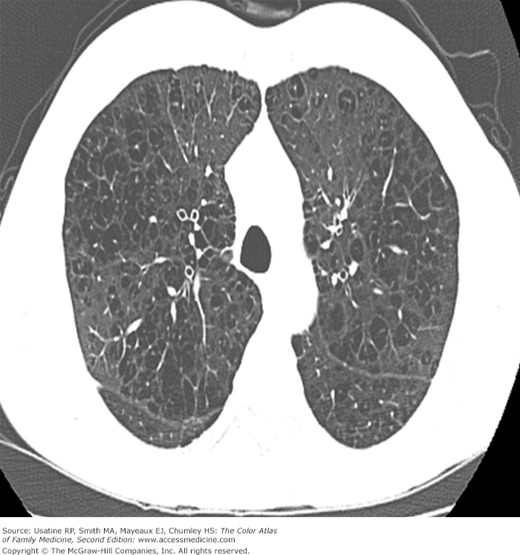

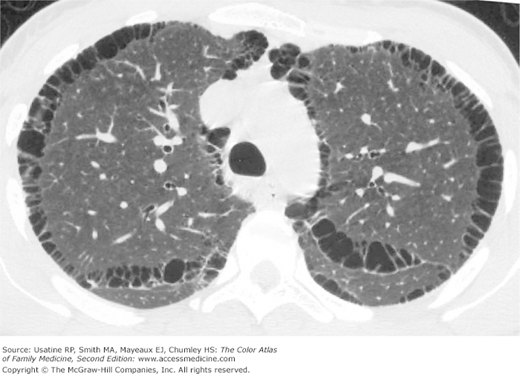

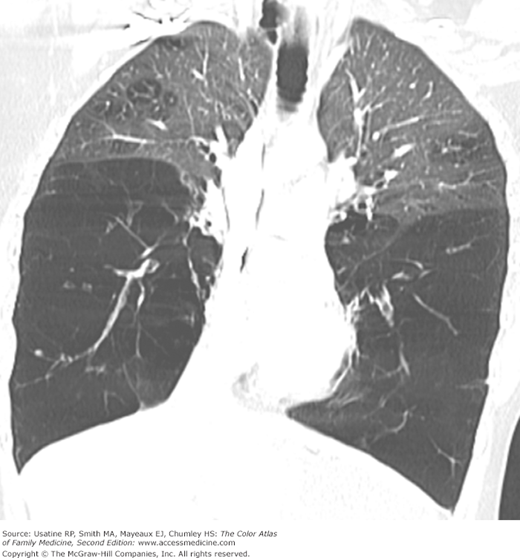

- Bullae are difficult to recognize in CXR but are easily seen on CT (Figures 56-4, 56-5, 56-6, 56-7, 56-8).

- Paucity of vascular markings in periphery (Figure 56-2).

- Pulmonary hypertension (CXR shows enlarged central pulmonary arteries).

- α1-Antitrypsine deficiency leads to early COPD even in nonsmokers. See Figure 56-9 for advanced pulmonary emphysema in a 30-year-old woman with α1-antitrypsine deficiency. The CXR shows increased lung volumes, flattening of the diaphragms, and a vertical heart. A CT may show extensive panlobular emphysema of the mid and lower lung zones (Figure 56-10). The vascular markings are prominent in the upper lobes, demonstrating “cephalization” of flow.

Figure 56-3

Posteroanterior (PA) radiograph showing flattened hemidiaphragms and decreased vascular markings from hyperinflation as a result of air trapping in a patient with COPD. (From Miller WT Jr. Diagnostic Thoracic Imaging. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006:108, Figure 3-40 A and B. Copyright 2006.)

Figure 56-4

Lateral view in the patient in Figure 56-2 showing increased anteroposterior (AP) diameter from hyperinflation as a result of air trapping in a patient with COPD. (From Miller WT Jr. Diagnostic Thoracic Imaging. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006:108, Figure 3-40 A and B. Copyright 2006.)

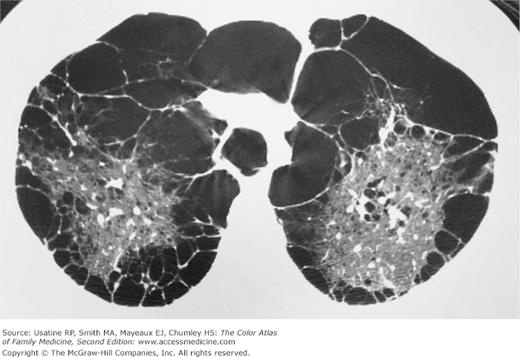

Figure 56-8

CT scan of the patient in Figure 56-6 (at the level of the pulmonary veins) showing multiple large peripheral bullae; the patient was diagnosed with severe paraseptal emphysema. (From Miller WT Jr. Diagnostic Thoracic Imaging. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006:111, Figure 3-42. Copyright 2006.)

Figure 56-10

CT of the chest in the same 30-year-old woman with α1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree