, Arthur H. Cohen2, Robert B. Colvin3, J. Charles Jennette4 and Charles E. Alpers5

(1)

Department of Pathology, Microbiology and Immunology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA

(2)

Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California, USA

(3)

Department of Pathology Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

(4)

Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA

(5)

Department of Pathology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA

Abstract

Chronic interstitial nephritis represents a large and diverse group of disorders characterized primarily by interstitial fibrosis with mononuclear leukocyte infiltration and tubular atrophy [1–3]. The chronic damage is unrelated to underlying glomerular or vascular processes. Among the many causes of chronic interstitial nephritis are high-grade vesicoureteral reflux, urinary obstruction, chronic bacterial infections, Sjögren’s syndrome, drugs (lithium, Chinese herbs), radiation, and Balkan nephropathy [3]. Although the pathologic aspects by light microscopy have the abovementioned features in common, historical information, imaging data, familial history, and gross pathology features may help to distinguish one disease from another. Because it was once widely considered that most chronic interstitial nephritis represented chronic infection, the term chronic pyelonephritis was commonly used for this group of disorders [1, 2]. However, chronic pyelonephritis is a rare entity [4].

Introduction/Clinical Setting

Chronic interstitial nephritis represents a large and diverse group of disorders characterized primarily by interstitial fibrosis with mononuclear leukocyte infiltration and tubular atrophy [1–3]. The chronic damage is unrelated to underlying glomerular or vascular processes. Among the many causes of chronic interstitial nephritis are high-grade vesicoureteral reflux, urinary obstruction, chronic bacterial infections, Sjögren’s syndrome, drugs (lithium, Chinese herbs), radiation, and Balkan nephropathy [3]. Although the pathologic aspects by light microscopy have the abovementioned features in common, historical information, imaging data, familial history, and gross pathology features may help to distinguish one disease from another. Because it was once widely considered that most chronic interstitial nephritis represented chronic infection, the term chronic pyelonephritis was commonly used for this group of disorders [1, 2]. However, chronic pyelonephritis is a rare entity [4].

Pathologic Findings

Gross Findings

As high-grade vesicoureteral reflux is such an important and representative form of chronic interstitial nephritis, it will be a large focus of this discussion. However, it should be emphasized that there is controversy regarding whether high-grade reflux alone can lead to chronic and progressive renal disease or whether reflux is a marker for abnormal renal development, which is the reason for reduced parenchyma with scarring [5, 6]. When examined grossly, the kidney in patients with reflux and chronic interstitial nephritis (also called reflux nephropathy) has scarring primarily and initially at the poles with dilated calyces and overlying thinned pale parenchyma. These areas have irregular, broad, deep scars with contraction. The other areas of kidney may be less affected or may have a finely granular surface indicating ischemic effect. The walls of the affected calyces and pelvis are thickened. In contrast to reflux, with obstruction there are diffuse pelvicalyceal dilatation and uniform parenchymal thinning. Calculi may or may not be evident. The renal surface is smooth or finely granular with only shallow scars induced by ischemia.

Light Microscopy

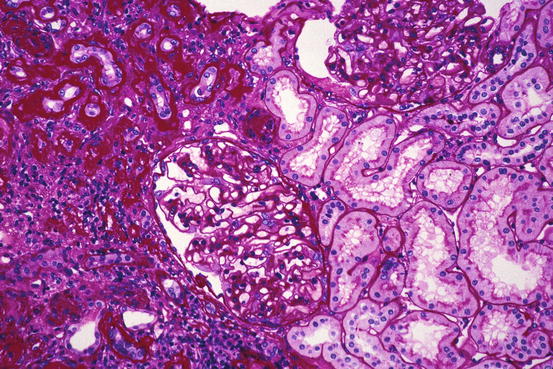

Microscopically, there is tubular atrophy with associated interstitial fibrosis, with areas of tubular dropout in more severe cases. Foci of thinned dilated tubules containing cast material may be seen (thyroidization), particularly in the outer cortex. Tubules focally are ruptured, and Tamm-Horsfall protein and other intraluminal contents are in extratubular locations. Mononuclear inflammatory cells including lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells are throughout the interstitium in large numbers (Figs. 14.1 and 14.2); lymphoid follicles may be observed. If active infection is still present, neutrophils and a small number of eosinophils may also be found. The calyces and pelvis disclose submucosal mononuclear leukocytes, fibrosis, and hypertrophy of the smooth muscle; the overlying transitional epithelium may be hyperplastic or display glandular or squamous metaplasia. Renal arteries often have intimal fibrosis and muscular hypertrophy, while glomeruli show ischemic collapse and periglomerular fibrosis. Glomeruli may have Tamm-Horsfall protein in Bowman’s space. In severe reflux nephropathy, there is hypertrophy of the glomeruli and tubules in the nonscarred parenchyma; there is sharp demarcation between the scarred and preserved parenchyma. Enlarged glomeruli may also be involved with focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis. Some investigators have reported that in nonscarred areas, glomeruli with elongated capillaries, adhesions, and podocyte detachment were associated with a poorer prognosis [4].