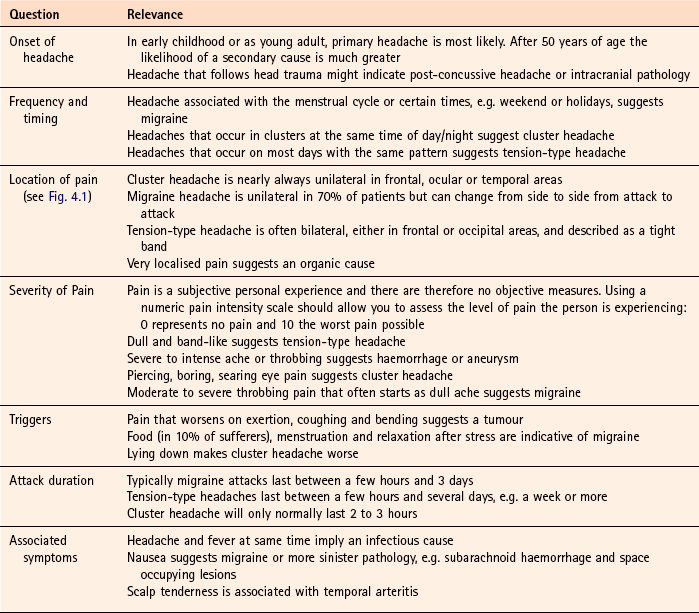

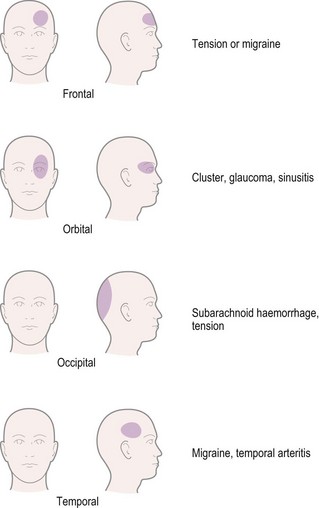

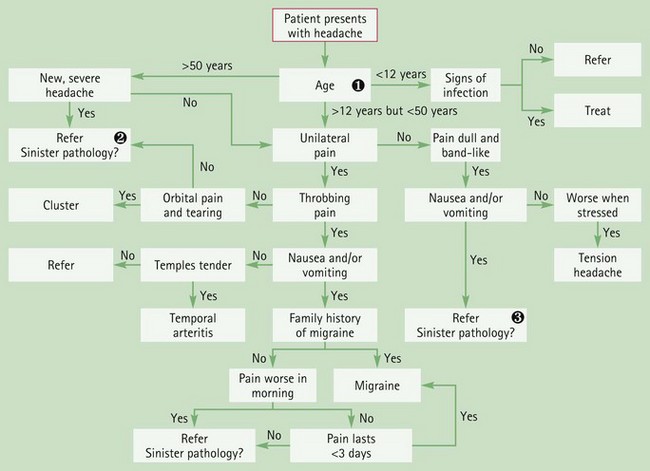

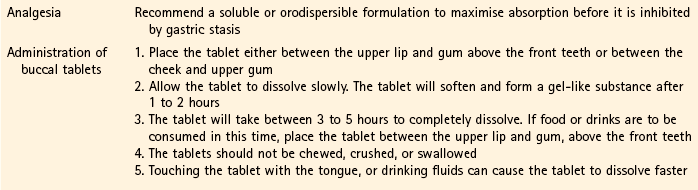

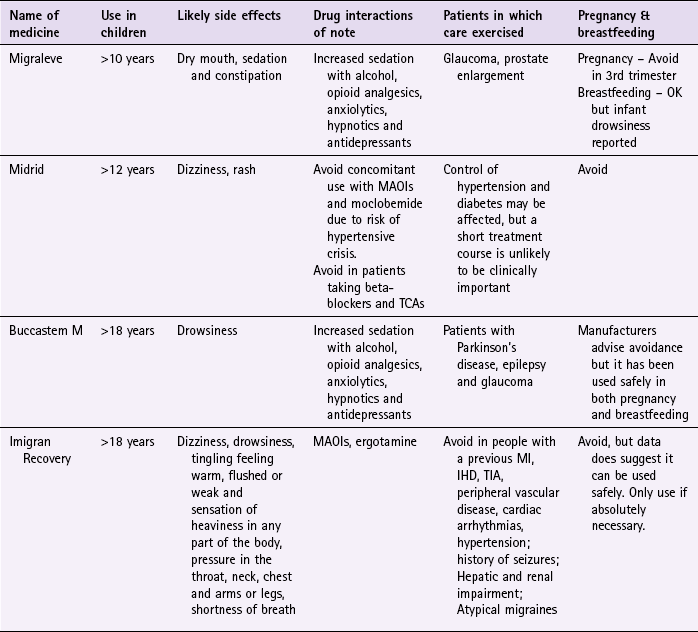

Chapter 4 Background Headache is not a disease state or condition but rather a symptom, of which there are many causes. Headache can be the major presenting complaint, for example in migraine, cluster and tension-type headache, or one of many symptoms, for example in an upper respiratory tract infection. Table 4.1 highlights those conditions that may be seen in a community pharmacy in which headache is one of the major presenting symptoms. Table 4.1 Causes of headache and their relative incidence in community pharmacy If the pharmacist is to advise on appropriate treatment and referral then it is essential to make an accurate diagnosis. However, with so many disorders having headache as a symptom pharmacists should endeavour to follow an agreed classification system. The third edition (2010) of the International Headache Society (IHS) classification is now almost universally accepted (Table 4.2). The system first distinguishes between primary and secondary headache disorders. This is useful to the community pharmacist, as any secondary headache disorder is symptomatic of an underlying cause and would normally require referral. In the IHS system, primary headaches are classified on symptom profiles, relying on careful questioning coupled with epidemiological data on the distribution a particular headache disorder has within the population. Table 4.2 The International Headache Society classification of headache Source: adapted by the British Association of Headache (BASH) from the International Headache Society Classification Subcommittee, The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd ed. Cephalalgia 2004, Blackwell Publishing, reproduced with permission. Given that headache is extremely common, and most patients will self-medicate, any patient requesting advice should ideally be questioned by the pharmacist, as it is likely that the headache has either not responded to OTC medication or is troublesome enough for the patient to seek advice. Arrival at an accurate diagnosis will rely exclusively on questioning; therefore a number of headache-specific questions should be asked (Table 4.3). In addition to these symptom-specific questions, the pharmacist should also enquire about the person’s social history because social factors – mainly stress – play a significant role in headache. Ask about the person’s work and family status to determine if the person is suffering from greater levels of stress than normal. In a community pharmacy the overwhelming majority of patients (80–90%) will present with tension-type headache. A further 10% will have migraine. Very few will have other primary headache disorders and fewer still will have a secondary headache disorder (see Table 4.1). Tension-type headaches can be classed as either episodic or chronic. Episodic tension-type headache can be further subdivided into infrequent and frequent forms. Most patients will present to the pharmacist with the infrequent episodic form. Headaches last from 30 minutes to up to 7 days in duration and often the patient will have a history of recent headaches. They might have tried OTC medication without complete symptom resolution or say that the headaches are becoming more frequent. Pain is bifrontal or bioccipital, generalised and non-throbbing (Fig. 4.1). The patient might describe the pain as tightness or a weight pressing down on their head. The pain is gradual in onset and tends to worsen progressively through the day. Pain is normally mild to moderate and not aggravated by movement, although it is often worse under pressure or stress. Nausea and vomiting are not associated with tension-type headache and rarely causes photo or phonophobia. Overall, the headache has a limited impact on the individual. • Phase one: premonitory phase (prodrome phase), which can occur hours or possibly days before the headache. The patient might complain of a change in mood or notice a change in behaviour. Feelings of well being, yawning, poor concentration and food cravings have been reported. These prodromal features are highly individual but are relatively consistent to each patient. Identification of ‘triggers’ is sometimes possible (Table 4.4). Table 4.4 Triggers and strategies to reduce migraine attacks • Phase two: headache with or without aura, • Phase three: as the headache subsides the patient can feel lethargic, tired and drained before recovery, which might take several hours and is termed the resolution phase. Eye strain: People that perform prolonged close work, for example VDU operators, can suffer from frontal aching headache. In the first instance, patients should be referred to an optician for a routine eye check. Cluster headache: Cluster headache is predominantly a condition that affects men over the age of 30. Typically the headache occurs at the same time each day with abrupt onset and lasts between 10 minutes and 3 hours, with 50% of patients experiencing night-time symptoms. Patients are woken 2 to 3 h after falling asleep with very intense unilateral orbital boring pain. Additionally, conjunctival redness, lacrimation, nasal congestion (which laterally becomes watery) are observed on the pain side of the head. Patients tend to be restless and irritable and move about to relieve the pain. Medication-overuse headache: Patients with long-standing symptoms of headache who regular medicate can develop medication-overuse headache. Pain receptors (nociceptors) instead of being ‘switched off’ when analgesics are taken are in fact ‘switched on’. The consequence is a cycle where patients take more and more painkillers that are stronger and stronger in order to control the pain. Patients will experience daily or near daily headaches that are described as dull and nagging. Obviously in these cases a medication history is essential and should prompt the pharmacist to refer the patient to the GP. Treatment is to stop all analgesia for a number of weeks and requires careful planning. Temporal arteritis: The temporal arteries that run vertically up the side of the head, just in front of the ear, can become inflamed. When this happens, they are tender to touch and might be visibly thickened. Unilateral pain is experienced and the person generally feels unwell with fever, myalgia and general malaise. Scalp tenderness is also possible, especially when combing the hair. It is most commonly seen in the elderly, especially women. Prompt treatment with oral corticosteroids is required as the retinal artery can become compromised, leading to blindness. Urgent referral is needed. Trigeminal neuralgia: Pain follows the course of either the second (maxillary; supplying the cheeks) or third (mandibular; supplying the chin, lower lip and lower cheek) division of the nerve leading to pain experienced in the cheek, jaws, lips or gums. Pain is short lived, usually lasting only a couple of minutes but is severe and lancing and is almost always unilateral. It is three times more common in women than men. Depression: A symptom of depression can be tension-type headaches. However, other more prominent symptoms should be present. The DSM-IV criteria are often used to aid a diagnosis of depression. The pharmacist should check for a loss of interest or pleasure in activities, fatigue, inability to concentrate, loss of appetite, weight loss, sleep disturbances and constipation. If the patient exhibits some of these characteristics then referral to the GP would be necessary. Recent changes to the patient’s social circumstances, for example loss of job, might also support your differential diagnosis. Glaucoma: Patients experience a frontal/orbital headache with pain in the eye. The eye appears red and is painful. Vision is blurred and the cornea can look cloudy. In addition, the patient might notice haloes around the vision. For further information on glaucoma see page 48. Meningitis: Severe generalised headache associated with fever, an obviously ill patient, neck stiffness, a positive Kernig’s sign (pain behind both knees when extended) and latterly a purpuric rash are classically associated with meningitis. However, meningitis is notoriously difficult to diagnose early and any child that has difficulty in placing their chin on their chest, has a headache and running a temperature above 38.9°C (102°F), should be referred urgently. Subarachnoid haemorrhage: The patient will experience very intense and severe pain, located in the occipital region. Nausea and vomiting are often present and a decreased lack of consciousness is prominent. Patients often describe the headache as the worse headache they have ever had. It is extremely unlikely that a patient would present in the pharmacy with such symptoms but if one did then immediate referral is needed. Conditions causing raised intracranial pressure: Space-occupying lesions (brain tumour, haematoma and abscess) can give rise to varied headache symptoms, ranging from severe chronic pain to intermittent moderate pain. Pain can be localised or diffuse and tends to be more severe in the morning with a gradual improvement over the next few hours. Coughing, sneezing, bending and lying down can worsen the pain. Nausea and vomiting are common. After a prolonged period of time neurological symptoms start to become evident, such as drowsiness, confusion, lack of concentration, difficulty with speech and paraesthesia. Figure 4.2 (and summary table in Case Study 4.1) will help in the differentiation of serious and non-serious causes of headache. Simple analgesia (paracetamol, aspirin and ibuprofen) have shown clinical benefit in relieving migraine attacks. A recent Cochrane review (Derry et al 2010) found that a single oral dose of paracetamol 1000 mg was effective in relieving moderate to severe migraine symptoms, compared with placebo. Approximately 20% of patients will be pain free in 2 hours (reduced from moderate to severe) and approximately 60% of patients can expect a reduction in the severity of pain from moderate/severe to mild pain by 2 hours. (Note that addition of metoclopramide saw efficacy equivalent to 100 mg sumatriptan – such products are available OTC in other countries, e.g. Australia.) Combinations of simple analgesics with codeine are available (page 263); however, there is doubt whether the amount of codeine in these preparations is sufficient to provide any additional pain relief. Further, there is growing evidence of problems with the over-use of these products resulting from dependence on the codeine components (Frei et al 2010). In response to the ongoing concerns about the over-use of codeine-containing products, the MHRA, in 2009, issued new guidance to restrict codeine-containing products for the short term (3 days) treatment of acute, moderate pain which is not relieved by paracetamol, ibuprofen or aspirin alone. A review of two trials in which Migraleve was compared against buclizine (Jorgensen 1974) and placebo (Scopa et al 1974) showed Migraleve was as effective as buclizine and superior to placebo in reducing severity of migraine attacks. However, patient numbers were small (n = 21 and 20 respectively) and statistical significance was not reported. Migraleve has also been compared to ergotamine-containing products; the standard drug at the time the trial was conducted. Results from a GP research group (Anon 1973) concluded that Migraleve was equally effective as Migril in treating migraine. However, results should be viewed with caution because the trial suffered from poor design, lacked randomisation, placebo or proper blinding. A further trial by Carasso and Yehuda (1984) also reported beneficial effects of Migraleve. The most recent trial (Adam 1987) was well designed, being double-blind, randomised and placebo controlled. The author concluded that, compared with placebo, Migraleve did reduce the severity of attacks significantly but not their total duration. Midrid capsules contain isometheptene mucate 65 mg and paracetamol 325 mg. A number of trials have investigated the effect of Midrid on reducing the severity of migraine attacks. Trials date back to 1948, although it was not until the 1970s that soundly designed trials were performed. Two studies (Diamond 1975, 1976) using similar methodology investigated isometheptene versus placebo and paracetamol. Both were double blind, placebo controlled and had identical inclusion criteria. The 1975 trial concluded that isometheptene was superior in relieving headache severity compared to placebo, although the dose of isometheptene used was double that found in Midrid. The 1976 trial also concluded that isometheptene was significantly superior to placebo and appeared to be better than paracetamol alone, but this did not reach statistical significance. A further trial (Behan 1978) compared Midrid against placebo and ergotamine. Fifty patients who suffered four or more migraine attacks per month were recruited to the study. Diary cards were completed for six attacks in which patients rated relief from headache on a four-point rating scale. The author concluded that Midrid was as effective as ergotamine and that both were more beneficial than placebo, although it is unclear whether this was statistically significant. Prescribing information relating to specific products used to treat migraine in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 4.5 and useful tips relating to patients presenting with migraine are given in Hints and Tips Box 4.1. Practical prescribing: Summary of medicines for migraine MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor; MI, myocardial infarction; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

Central nervous system

Headache

Incidence

Cause

Most likely

Tension-type headache

Likely

Migraine, sinusitis, eye strain

Unlikely

Cluster headache, medication-overuse headache, temporal arteritis, trigeminal neuralgia, depression

Very unlikely

Glaucoma, meningitis, subarachnoid haemorrhage, raised intracranial pressure

Headache classification

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

Clinical features of headache

Tension-type headache

Migraine

Trigger

Strategy

Stress

Maintain regular sleep pattern

Take regular exercise

Modify work environment

Relaxation techniques, e.g. yoga

Diet

Any food can be a potential trigger but food implicated includes:

Cheese

Citrus fruit

Chocolate

Maintain a food diary. If an attack occurs within 6 h of food ingestion and is reproducible it is likely that it is a trigger for migraine

Eat regularly and do not skip meals

Note: Detecting triggers is complicated because they appear to be cumulative, jointly contributing to a ‘threshold’ above which attacks are initiated.

Other likely causes of headache

Unlikely causes

Very unlikely causes

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Migraleve

Midrid

Practical prescribing and product selection

![]() Table 4.5

Table 4.5

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Central nervous system