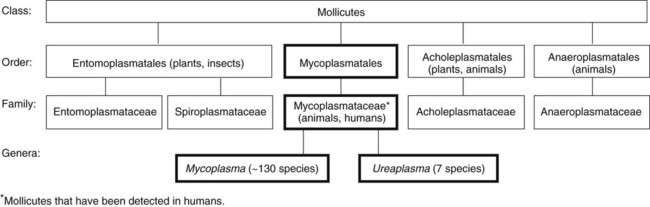

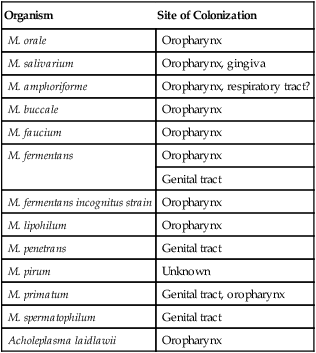

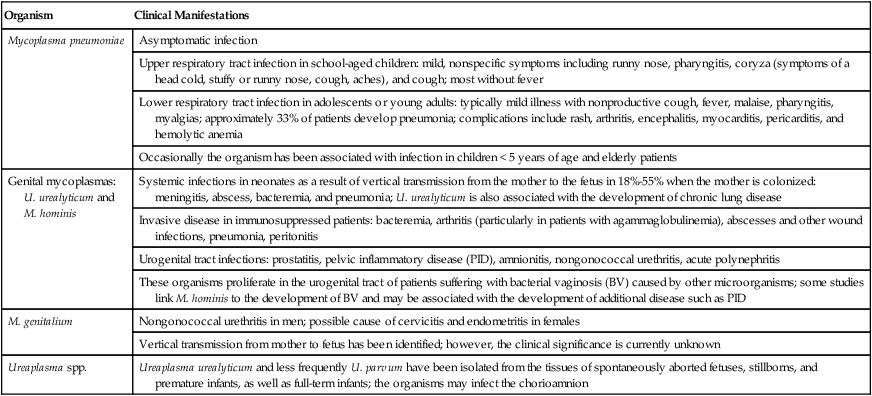

1. Describe the general characteristics of the Mycoplasmataceae, including microscopic and macroscopic appearance. 2. Identify key characteristic biochemical reactions for the differentiation of pathogenic Mycoplasma spp. 3. Explain the difficulties associated with isolation of these fastidious organisms, including nutritional requirements, immune response, cellular locations, and incubation requirements (length of time, temperature, and oxygenation requirements). 4. Compare the clinical presentation of M. pneumoniae to S. pneumoniae. 5. Describe the proper processing, collection, transport, and storage of specimens for the isolation of the organism discussed in this chapter. 6. State the site for colonization in the human host for M. genitalium, M. hominis, M. pneumoniae, and U. urealyticum. 7. Describe the clinical manifestations associated with each of the major species considered in this chapter. 8. Describe the complications of serologic diagnosis related to the variation in antibody formation in infection with M. pneumoniae. 9. Explain the current limitations and recommendations associated with susceptibility testing related to the Mycoplasmataceae. 10. Correlate signs and symptoms and evaluate laboratory data associated with the diagnosis of infections caused by the major pathogens discussed in this chapter. Organisms in this chapter belong to the class Mollicutes (Latin, meaning soft skin). This class comprises four orders, which, in turn, contain five families and eight genera (Figure 45-1). The mycoplasmas that colonize or infect humans belong to the family Mycoplasmataceae; this family comprises two genera, Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma. These organisms are highly fastidious, are slow growing, and most are facultative anaerobes that require nucleic acid precursor molecules, fatty acids, and sterols such as cholesterol for growth. These bacteria have a very small cell size (0.3 × 0.8 µm) and small genome. The Mollicutes appear most closely related to the gram-positive bacterial subgroup that includes bacilli, streptococci, and lactobacteria that diverged from the Streptococcus branch of gram-positive bacteria. The mycoplasmas usually considered as commensals are listed in Table 45-1, along with their respective sites of colonization. These organisms may be transmitted by direct sexual contact, transplanted tissue from donor to recipient, or from mother to fetus during childbirth or in utero. M. pneumoniae may be transmitted by respiratory secretions. One species of Acholeplasma (these organisms are widely disseminated in animals), Acholeplasma laidlawii, has been isolated from the oral cavity of humans a limited number of times; however, the significance of these mycoplasmas and their colonization of humans remains uncertain. TABLE 45-1 Mycoplasmas That Are Considered Normal Flora of the Oropharynx or Genital Tract M. pneumoniae is a cause of community-acquired atypical pneumonia, often referred to as walking pneumonia (see Chapter 69); infections caused by this agent are distributed worldwide, with an estimated 2 million cases per year in the United States. M. pneumoniae infection may also result in bronchitis or pharyngitis. M. pneumoniae may be transmitted person-to-person by respiratory secretions as previously stated or indirectly by inanimate objects contaminated with respiratory secretions (fomites). Infections can occur singly or as outbreaks in closed populations such as families and military recruit camps. Pneumonia caused by M. pneumoniae may present as asymptomatic to mild disease, with early nonspecific symptoms including malaise, fever, headache, sore throat, earache, and nonproductive cough. This differs significantly from the classic symptoms associated with pneumonia as a result of infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae (see Chapters 15 and 69). M. pneumoniae strongly attaches to the mucosal cells and may reside intracellularly within host cells, resulting in a chronic persistent infection that may last for months to years. The infections do not follow seasonal patterns as seen with influenzae and other respiratory pathogens. Besides respiratory infection, M. pneumoniae can cause extrapulmonary manifestations such as pericarditis, hemolytic anemia, arthritis, nephritis, Bell’s palsy, and meningoencephalitis resulting in various additional forms of paralysis. The clinical manifestations of infections caused by M. pneumoniae and the pathogenic genital mycoplasmas, U. urealyticum, U. parvum, M. hominis, and M. genitalium are summarized in Table 45-2. TABLE 45-2 Data from Versalovic J: Manual of clinical microbiology, ed 10, Washington, DC, 2011, ASM Press. Because mycoplasmas have no cell wall, they are highly susceptible to drying; therefore, transport media are necessary, particularly when specimens are collected on swabs. Liquid specimens such as body fluids do not require transport media if inoculated to appropriate media within 1 hour of collection. Tissues should be kept moist; if a delay in processing is anticipated, they should also be placed in transport media. Specific media for the isolation of Mycoplasma spp. include those containing 10% heat-inactivated calf serum containing 0.2 M sucrose in a 0.02 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, such as SP4, Shepard’s 10B broth or 2 SP. Additional commercial media available for cultivation of these organisms include Stuart’s medium, trypticase soy broth supplemented with 0.5% bovine serum albumin, Mycotrans (Irvine Scientific, Irvine, California), and A3B broth (Remel, Inc.). Excessive delays in processing can result in decreased viability and recovery of organisms from clinical specimens. If the storage time is expected to exceed 24 hours prior to cultivation, the samples should be placed in transport media and frozen at −80°C. Frozen samples should be thawed in a hot water bath at 37°C. Transport and storage conditions of various types of specimens are summarized in Table 45-3. TABLE 45-3 Transport and Storage Conditions for Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Ureaplasma urealyticum, and M. hominis

Cell Wall–Deficient Bacteria

Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma

General Characteristics

Epidemiology and Pathogenesis

Epidemiology

Organism

Site of Colonization

M. orale

Oropharynx

M. salivarium

Oropharynx, gingiva

M. amphoriforme

Oropharynx, respiratory tract?

M. buccale

Oropharynx

M. faucium

Oropharynx

M. fermentans

Oropharynx

Genital tract

M. fermentans incognitus strain

Oropharynx

M. lipohilum

Oropharynx

M. penetrans

Genital tract

M. pirum

Unknown

M. primatum

Genital tract, oropharynx

M. spermatophilum

Genital tract

Acholeplasma laidlawii

Oropharynx

Spectrum of Disease

Organism

Clinical Manifestations

Mycoplasma pneumoniae

Asymptomatic infection

Upper respiratory tract infection in school-aged children: mild, nonspecific symptoms including runny nose, pharyngitis, coryza (symptoms of a head cold, stuffy or runny nose, cough, aches), and cough; most without fever

Lower respiratory tract infection in adolescents or young adults: typically mild illness with nonproductive cough, fever, malaise, pharyngitis, myalgias; approximately 33% of patients develop pneumonia; complications include rash, arthritis, encephalitis, myocarditis, pericarditis, and hemolytic anemia

Occasionally the organism has been associated with infection in children < 5 years of age and elderly patients

Genital mycoplasmas: U. urealyticum and M. hominis

Systemic infections in neonates as a result of vertical transmission from the mother to the fetus in 18%-55% when the mother is colonized: meningitis, abscess, bacteremia, and pneumonia; U. urealyticum is also associated with the development of chronic lung disease

Invasive disease in immunosuppressed patients: bacteremia, arthritis (particularly in patients with agammaglobulinemia), abscesses and other wound infections, pneumonia, peritonitis

Urogenital tract infections: prostatitis, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), amnionitis, nongonococcal urethritis, acute polynephritis

These organisms proliferate in the urogenital tract of patients suffering with bacterial vaginosis (BV) caused by other microorganisms; some studies link M. hominis to the development of BV and may be associated with the development of additional disease such as PID

M. genitalium

Nongonococcal urethritis in men; possible cause of cervicitis and endometritis in females

Vertical transmission from mother to fetus has been identified; however, the clinical significance is currently unknown

Ureaplasma spp.

Ureaplasma urealyticum and less frequently U. parvum have been isolated from the tissues of spontaneously aborted fetuses, stillborns, and premature infants, as well as full-term infants; the organisms may infect the chorioamnion

Laboratory Diagnosis

Specimen Collection, Transport, and Processing

Specimen Type

Transport Conditions

Transport Media (examples)§

Storage

Processing

Body fluid or liquid specimens*

Within 1 hr of collection on ice or at 4° C

Not required

4° C up to 24 hr†

Concentrate by high-speed centrifugation and dilute (1 : 10 to 1 : 1000) in broth culture media to remove inhibitory substances and contaminating bacteria; urine should be filtered through a 0.45-µm pore size filter

Swabs

Place immediately into transport media

0.5% albumin in trypticase soy broth modified Stuart’s

4°C up to 24 hr†

None

2SP (sugar-phosphate medium with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum)

Shepard’s 10B broth for ureaplasmas

SP-4 broth for other mycoplasmas and M. pneumoniae‡

Mycoplasma transport medium (trypticase phosphate broth, 10% bovine serum albumin, 100,000 U of penicillin/milliliter and universal transport media [Copan, Murrieta, CA])

Tissue

Within 1 hr of collection on ice or at 4° C

Not required as long as prevented from drying out

4° C up to 24 hr†

Mince (not ground) and dilute (1 : 10 and 1 : 100) in transport media ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Cell Wall–Deficient Bacteria: Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma