CHAPTER 13 Cardiac Muscle

The function of the heart is to pump blood through the circulatory system, and this is accomplished by the highly organized contraction of cardiac muscle cells. Specifically, the cardiac muscle cells are connected together to form an electrical syncytium, with tight electrical and mechanical connections between adjacent cardiac muscle cells. An action potential initiated in a specialized region of the heart (e.g., the sinoatrial node) is therefore able to pass quickly throughout the heart to facilitate synchronized contraction of the cardiac muscle cells, which is important for the pumping action of the heart. Likewise, refilling of the heart requires synchronized relaxation of the heart, with abnormal relaxation often resulting in pathological conditions.

BASIC ORGANIZATION OF CARDIAC MUSCLE CELLS

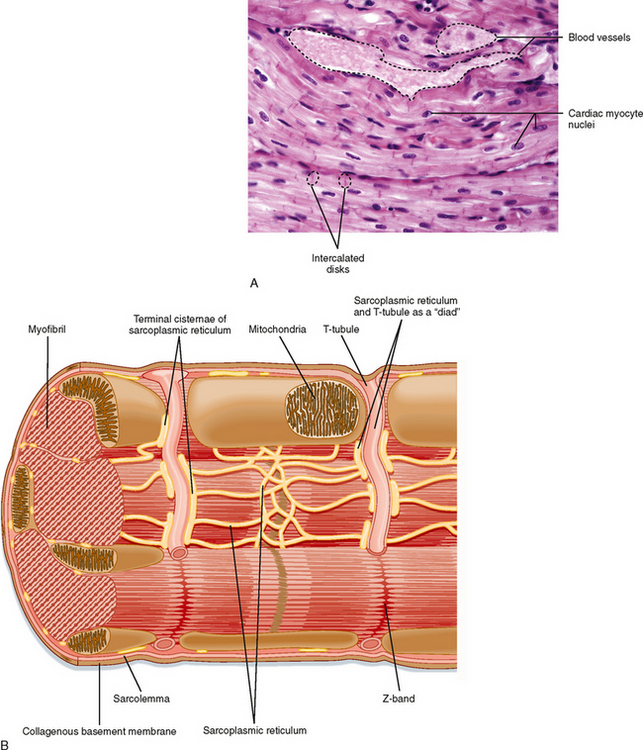

Cardiac muscle cells are much smaller than skeletal muscle cells. Typically, cardiac muscle cells measure 10 μm in diameter and approximately 100 μm in length. As shown in Figure 13-1, A, cardiac cells are connected to each other through intercalated disks, which include a combination of mechanical junctions and electrical connections. The mechanical connections, which keep the cells from pulling apart when contracting, include the fascia adherens and desmosomes. Gap junctions between cardiac muscle cells, on the other hand, provide electrical connections between cells to allow propagation of the action potential throughout the heart. Thus, the arrangement of cardiac muscle cells within the heart is said to form an electrical and mechanical syncytium that allows a single action potential (generated within the sinoatrial node) to pass throughout the heart so that the heart can contract in a synchronous, wave-like fashion. Blood vessels course through the myocardium.

The basic organization of thick and thin filaments in cardiac muscle cells is comparable to that seen in skeletal muscle (see Chapter 12). When viewed by electron microscopy, there are repeating light and dark bands that represent I bands and A bands, respectively (Fig. 13-1, B). Thus, cardiac muscle is classified as a striated muscle. The Z line transects the I band and represents the point of attachment of the thin filaments. The region between two adjacent Z lines represents the sarcomere, which is the contractile unit of the muscle cell. The thin filaments are composed of actin, tropomyosin, and troponin and extend into the A band. The A band is composed of thick filaments, along with some overlap of thin filaments. The thick filaments are composed of myosin and extend from the center of the sarcomere toward the Z lines.

Myosin filaments are formed by a tail-to-tail association of myosin molecules in the center of the sarcomere, followed by a head-to-tail association as the thick filament extends toward the Z lines. Thus, the myosin filament is polarized and poised for pulling the actin filaments toward the center of the sarcomere. A cross section of the sarcomere near the end of the A band shows that each thick filament is surrounded by six thin filaments and each thin filament receives cross-bridge attachments from three thick filaments. This complex array of thick and thin filaments is characteristic of both cardiac and skeletal muscle and helps stabilize the filaments during muscle contraction (see Fig. 12-3, B, for the hexagonal array of thick and thin filaments in the sarcomere of striated muscle).

The thick filaments are tethered to the Z lines by a large elastic protein called titin. Although titin was postulated to tether myosin to the Z lines and thus prevent overstretching of the sarcomere, there is evidence indicating that titin may participate in cell signaling (perhaps by acting as a stretch sensor and thus modulating protein synthesis in response to stress). Such signaling by titin has been observed in both cardiac and skeletal muscle cells. Moreover, genetic defects in titin result in atrophy of both cardiac and skeletal muscle cells and may contribute to both cardiac dysfunction and skeletal muscle dystrophies (recently termed titinopathies). Titin is also thought to contribute to the ability of cardiac muscle to increase force upon stretch (discussed later).

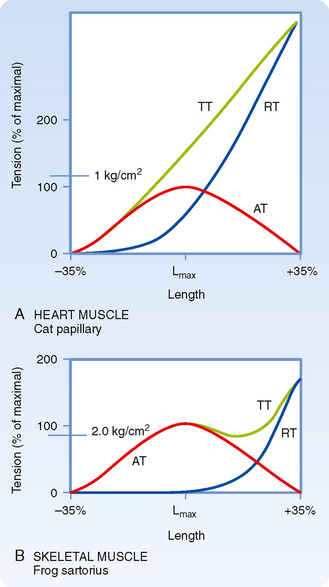

Although cardiac muscle and skeletal muscle both contain an abundance of connective tissue, there is more connective tissue in the heart. The abundance of connective tissue in the heart helps prevent muscle rupture (as in skeletal muscle), but it also prevents overstretching of the heart. Length-tension analysis of cardiac muscle, for example, shows a dramatic increase in passive tension as cardiac muscle is stretched beyond its resting length (Fig. 13-2). Skeletal muscle, by contrast, tolerates a much greater degree of stretch before passive tension increases to a comparable level. The reason for this difference between cardiac and skeletal muscle is not known, although one possibility is that stretch of skeletal muscle is typically limited by the range of motion of the joint, which in turn is limited by the ligaments/connective tissue surrounding the joint. The heart, on the other hand, appears to rely on the abundance of connective tissue around cardiac muscle cells to prevent overstretching during periods of increased venous return. During intense exercise, for example, venous return may increase fivefold. However, the heart is capable of pumping this extra volume of blood into the arterial system with only minor changes in the ventricular volume of the heart (i.e., end-diastolic volume increases less than 20%). Although the abundance of connective tissue in the heart limits stretch of the heart during these periods of increased venous return, additional regulatory mechanisms help the heart pump the extra blood that it receives (as discussed later). Conversely, if the heart were to be overstretched, the contractile ability of cardiac muscle cells would be expected to decrease (because of decreased overlap of the thick and thin filaments), thereby resulting in insufficient pumping, increased venous pressure, and perhaps pulmonary edema.

Within cardiac muscle cells, myofibrils are surrounded by the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), an internal network of membranes (Fig. 13-1, B). This is similar to skeletal muscle except that the SR in the heart is less dense and not as well developed. Terminal regions of the SR abut the T tubule or lie just below the sarcolemma (or both) and play a key role in the elevation of intracellular [Ca++] during an action potential. The mechanism by which an action potential initiates release of Ca++ in the heart, however, differs significantly from that in skeletal muscle (as discussed later). The heart contains an abundance of mitochondria, with up to 30% of the volume of the heart being occupied by these organelles. The high density of mitochondria provides the heart with great oxidative capacity, more so than typically seen in skeletal muscle.

The sarcolemma of cardiac muscle also contains invaginations (T tubules), comparable to those seen in skeletal muscle. In cardiac muscle, however, T tubules are positioned at the Z lines, whereas in mammalian skeletal muscle, T tubules are positioned at the ends of the I bands. In cardiac muscle there also tends to be fewer and less well developed connections between the T tubules and the SR than in skeletal muscle.

CONTROL OF CARDIAC MUSCLE ACTIVITY

Cardiac muscle is an involuntary muscle with an intrinsic pacemaker. The pacemaker represents a specialized cell (located in the sinoatrial node of the right atrium) that is able to undergo spontaneous depolarization and generate action potentials. It is important to note that although several cells in the heart are able to depolarize spontaneously, the fastest spontaneous depolarizations occur in cells in the sinoatrial node. Moreover, once a given cell spontaneously depolarizes and fires an action potential, this action potential is then propagated throughout the heart (by specialized conduction pathways and cell-to-cell contact). Thus, depolarization from only one cell is needed to initiate a wave of contraction in the heart (i.e., heartbeat). The mechanism or mechanisms underlying this spontaneous depolarization are discussed in depth in Chapter 16.

As shown in Figure 16-17, once an action potential is initiated in the sinoatrial node, it is propagated between atrial cells via gap junctions, as well as through specialized conduction fibers in the atria. The action potential can pass throughout the atria within approximately 70 msec. For the action potential to reach the ventricles, it must pass through the atrioventricular node, after which the action potential passes throughout the ventricle via specialized conduction pathways (bundle of His and Purkinje system) and gap junctions in the intercalated disks of adjacent cardiac myocytes. The action potential can pass through the entire heart within 220 msec after initiation in the sinoatrial node. Because contraction of a cardiac muscle cell typically lasts 300 msec, this rapid conduction promotes nearly synchronous contraction of heart muscle cells. This is a very different scenario from that of skeletal muscle, where cells are grouped into motor units that are recruited independently as the force of contraction is increased.

Excitation-Contraction Coupling

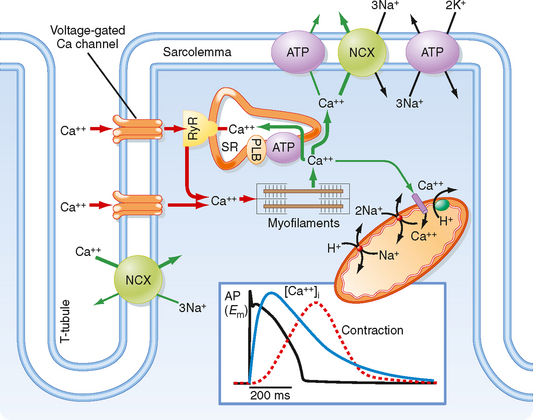

Examination of the action potential in cardiac muscle reveals a prolonged action potential lasting 150 to 300 msec (Fig. 13-3), which is substantially longer than the action potentials in skeletal muscle (≈5 msec). The long action potential duration in cardiac muscle is due to a slow inward Ca++ current through a voltage-gated L-type Ca++ channel in the sarcolemma. The amount of Ca++ coming into the cardiac muscle cell is relatively small and serves as a trigger for release of Ca++ from the SR. In the absence of extracellular Ca++, one is still able to initiate an action potential in cardiac muscle, although it is considerably shorter in duration and unable to initiate a contraction. Thus, influx of Ca++ during the action potential is critical for triggering release of Ca++ from the SR and thus initiating contraction.

In each cardiac muscle sarcomere, terminal regions of the SR abut T tubules and the sarcolemma (Figs. 13-1, B, and 13-3). These junctional regions of the SR are enriched in ryanodine receptors (RYRs; an SR Ca++ release channel). The RYR is a Ca++-gated Ca++ channel, so influx of Ca++ during an action potential is able to initiate release of Ca++ from the SR in cardiac muscle. The amount of Ca++ released into the cytosol from the SR is much greater than that entering the cytosol from the sarcolemma, although release of Ca++ from the SR does not occur without this entry of “trigger” Ca++. This contrasts with skeletal muscle, where release of Ca++ from the SR does not involve entry of Ca++ across the sarcolemma but instead results from a voltage-induced conformational change in the DHPR. Thus, excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac muscle is termed electrochemical coupling (involving Ca++-induced release of Ca++), whereas excitationcontraction coupling in skeletal muscle is termed electromechanical coupling (involving direct interactions between the DHPR in the T tubule and the RYR in the SR). The basis for this difference in Ca++ release mechanisms appears to depend on the DHPR isoform because expression of cardiac DHPR in skeletal muscle cells results in a requirement for extracellular Ca++ for contraction of these modified skeletal muscle cells.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree