71

Cardiac Infections

CHAPTER CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Cardiac infections are severe, life-threatening infections in many cases. The heart valves (endocardium), myocardium, and pericardium can all be infected. In addition, infection of cardiac devices (pacemakers, defibrillators) is becoming more frequently diagnosed with their increase in use. Diagnosis of cardiac infection can be challenging and usually requires a combination of microbiologic testing and cardiac imaging. Treatment often requires antimicrobial therapy but may also require surgical management for cure.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING FOR CARDIAC INFECTIONS

Electrocardiogram

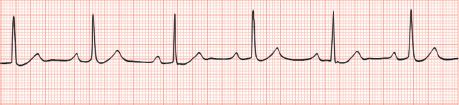

An electrocardiogram (ECG) measures electrical activity in the heart using noninvasive monitoring with leads attached to the skin. Cardiac infections can cause disease-specific ECG changes, which can assist in diagnosis.

Echocardiogram

Echocardiography uses Doppler ultrasound to visualize structures and flow of blood through the heart. The test is very helpful in diagnosing most types of cardiac infections. There are two types of echocardiograms, a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE), where the probe is placed on the chest wall, and a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE), where the probe is inserted into the esophagus. The TEE often produces higher-quality images, particularly of aortic and mitral valves, since the TEE probe is closer to the heart itself.

ENDOCARDITIS

Definition

Endocarditis is an infection of the valves of the heart.

Pathophysiology

Infection of the heart valves is thought to result from the colonization of damaged valvular endothelium by circulating pathogens. Endothelial damage may result from turbulent blood flow around the valve (congenital or rheumatic heart disease), direct injury from foreign bodies (e.g., intravenous catheters), or repeated intravenous injections of particles in intravenous drug users. Organisms enter the bloodstream most often at the site of dental surgery, indwelling intravenous catheters, or intravenous drug use. Adhesion of bacteria to the damaged endothelium is enhanced by their ability to produce a glycocalyx.

Once the infection has begun, a combination of organisms and thrombus organize to form a vegetation (Figure 71–1). Destruction of the valve occurs at different rates depending on the virulence of the organism. As the valve is destroyed, symptoms of valvular regurgitation can develop. Organisms can spread to surrounding myocardium, resulting in abscess formation and destruction of the electrical conduction system. As the vegetation on the valve enlarges, fragments can spread via the bloodstream (emboli), resulting in catastrophic effects, such as cerebrovascular accidents (CVA). Prolonged infection as seen in subacute endocarditis can result in antigen–antibody complex formation. Deposition of these complexes can result in other clinical manifestations as described in the next section. Artificial materials within the heart, such as prosthetic heart valves, pacemakers, and defibrillators, serve as potential sites for infection.

FIGURE 71–1 Endocarditis. Note vegetations on mitral valve. Black arrows point to vegetations. (Reproduced with permission from Longo DL et al (eds). Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2012, p 1052. Copyright © 2012 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.)

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations of infective endocarditis can include any of the following listed below. Depending on the virulence of the infecting pathogen, the time course of illness may be days (acute endocarditis; caused by, for example, Staphylococcus aureus) or weeks to months (subacute endocarditis; caused by, for example, viridans group streptococci).

• Constitutional symptoms: fever (>80% cases), chills, night sweats, anorexia

• Consequences of destruction of heart valves and associated structures: new murmur, heart failure, atrioventricular (AV) block (PR prolongation seen on ECG; Figure 71–2)

FIGURE 71–2 Atrioventricular block with sinus bradycardia. (Reproduced with permission from McKean SC et al. Principles and Practice of Hospital Medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2012. Copyright © 2012 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.)

• Embolic phenomena:

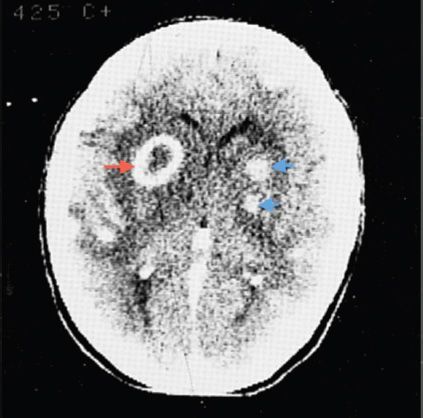

• Left-sided endocarditis: CVAs or brain abscess (Figure 71–3) (new focal neurologic deficits), splenic or renal infarcts (abdominal or flank pain), and emboli to others sites manifesting as splinter hemorrhages (Figure 71–4), Janeway lesions (Figure 71–5), retinal hemorrhages (Figure 71–6) and conjunctival hemorrhages

FIGURE 71–3 Brain abscess. Red arrow points to a characteristic ring-enhancing lesion. The blue arrows point to two additional abscesses. (Reproduced with permission from Ropper AH, Samuels MA. Adams and Victor’s Principles of Neurology. 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2009. Copyright © 2009 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.)

FIGURE 71–4 Splinter hemorrhage. Red arrow points to a splinter hemorrhage under the finger nail. (Used with permission from Usatine RP et al. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree