Chapter Fifty-Five. Breastfeeding practice and problems

Introduction

Infant feeding affects every child for life, in many ways known and as yet unknown in other ways (Minchin 1998). Human milk nourishes the newborn, provides protection for child development in early and later life and is optimal for promoting closeness between mother and baby. In mammals, learning about breastfeeding is part of a lifelong process which begins at birth; some is instinctive but a lot is social learning and involves seeing breastfeeding as being a normal and welcome sight, involving shared experiences within the family or community. However, beliefs and attitudes about breastfeeding are very much dependent and influenced by culture, folklore and social context. For example, colostrum is accepted and encouraged as the first food for the baby in many cultures while other cultures believe colostrum to be ‘old’ milk and unfit for the newborn.

The majority of women are physiologically capable of breastfeeding and when this is not possible then formula milk is available for the baby as an inferior alternative. The art of breastfeeding is a specialised aspect of the science of lactation and is at risk of being lost to future generations because mothers in developed countries may choose to formula-feed in favour of breastfeeding. This is concerning and makes it even more necessary to protect and support breastfeeding practices.

Although breastfeeding is partly instinctive behaviour, mothers will still need support, encouragement and good management to make breastfeeding a success. Breastfeeding is something that has to be learnt. This is true for most new mothers and it is certainly true for midwives and for other health professionals providing care and support. The information in this chapter may help to supply knowledge and information to those involved in helping mothers to successfully establish breastfeeding.

Benefits of breastfeeding

Human milk is easily digested and nutritionally balanced to meet the baby’s needs. The benefits of breastfeeding for babies and mothers are well recognised in the current literature and it is useful to consider the benefits of breast milk and breastfeeding separately because the benefits are more than simply the advantages of feeding a baby on breast milk (UNICEF/WHO 2008). Health professionals should share information about the benefits with women and partners when they are making a choice about feeding their baby.

The WHO has recently commissioned a review of the evidence available through a series of systematic reviews to establish the long-term impact of breastfeeding on health. The evidence from two recent reviews suggests that there may be long-term benefits. Horta et al (2007) reported that breastfed subjects experienced lower mean blood pressure and total cholesterol, as well as higher performance in intelligence tests. A review from the USA investigated the effects of breastfeeding in developed countries (Ips et al 2007). The reviewers concluded that a history of breastfeeding was associated with numerous health benefits including a reduction in the risk of otitis media, non-specific gastroenteritis, severe lower respiratory tract infections, atopic dermatitis, asthma in young children, obesity, type 1 and 2 diabetes, childhood leukemia, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and neonatal necrotising enterocolitis. For maternal outcomes, a history of lactation was associated with a reduced risk of type 2 diabetes and breast and ovarian cancer. Early cessation of breastfeeding or not breastfeeding was found to be associated with an increased risk of maternal postpartum depression.

Two other recent studies investigating lung function in children have reported significantly increased lung volume recordings for children who had been breastfed for at least 4 months (Ogbuana et al 2008) and breastfeeding had a favourable influence on lung growth in children (Mahr 2008). A large prospective study (7223 mother–infant pairs) was carried out in Australia over a 15-year period to establish if there was a protective effect of breastfeeding on maternally perpetrated child maltreatment. Findings concluded that breastfeeding, among other factors, may help to protect children against maltreatment by their mothers, particularly child neglect (Strathearn et al 2009).

Breastfeeding may also have a positive effect for babies in relation to interpersonal relationships and sleeping patterns (Renfrew et al 2000). Babies are known to cry less if they stay close to their mothers and breastfeed from birth (Christensson et al 1995). Breastfeeding also helps the mother and baby form a close relationship and is emotionally satisfying for the mother. All of these factors can benefit the whole family emotionally and economically and improve their overall quality of life.

Physiology applied to practice

In Western countries it is rare for a young woman to hold a newborn baby until she bears her own and even rarer for her to closely observe breastfeeding. A primipara is therefore faced with the need to rapidly acquire these two skills without the benefit of prior experience. Midwives must be knowledgeable about the physiology of lactation and apply this to practice if they are going to help mothers to breastfeed. The baby needs adequate nourishment at the breast and the mother must be enabled to develop the necessary skills to feed the baby herself.

In recent years, a number of common breastfeeding practices have been shown to be unhelpful or detrimental to breastfeeding success. These practices were discontinued and included the separation of mothers and babies, restricted feeding and duration of breastfeeding and test weighing babies. The following practices were promoted when they were found to be beneficial in achieving breastfeeding success:

• Early discharge from hospital: women who went home within 48 h were more likely to be breastfeeding at 6 months postpartum (Renfrew & Lang 1999).

• Provision of extra support to breastfeeding mothers increased breastfeeding until the age of 2 months (Sikorski et al 2001).

Antenatal preparation

The decision to breastfeed by women in this society is often made before pregnancy or very early in pregnancy, whereas women tend to make the decision to formula-feed later in pregnancy (RCM 2002). Women are unlikely to change their minds once the decision is made.

During this time, midwives should adopt a sensitive approach with women to help them make their own decision about baby feeding. Women who wish to breastfeed or are undecided should be given all the information and support they require during pregnancy. It may be a bit more difficult to give information to some women who have decided to formula-feed. Women who choose to formula-feed will also be given any information and support needed during pregnancy.

Preparation of the nipples is not necessary other than advising women to keep normal standards of cleanliness and wear a well-supporting bra. Women with nipple problems may find their nipple shape improves as pregnancy proceeds. Breast shells and Hoffman’s exercises are ineffective in the preparation of problem nipples (Main Trial Collaborative Group 1994). Teaching pregnant women about breastfeeding physiology and skills may be more important.

The first feed

Mothers should hold their babies with skin contact at birth or within 30 min of delivery and they should be encouraged to give the first breastfeed as soon as the baby is receptive. This should be unhurried as it is important that time is taken to achieve a successful first feed. Health professionals need to know what constitutes good breast attachment to enable them to facilitate mothers appropriately with the initiation of breastfeeding. The mothers need to know how to breastfeed their baby and learn how to hold and position the baby and often they need help with this.

There are several reasons why early and frequent breastfeeding is beneficial for the mother and the baby (summarised in UNICEF/WHO 2008):

• Suckling stimulates uterine contractions, aids expulsion of the placenta and helps to control blood loss.

• The early removal of milk creates the optimum impetus for the development and sensitivity of prolactin receptors, which ensures early milk production.

• The baby’s suckling reflex is usually most intense 45 min through the 2nd hour of labour. Initiate soon after birth to prevent any delay in gratification for the baby.

• The baby begins to get the immunological benefits of colostrum.

• The baby’s digestive peristalsis is stimulated.

• Breast engorgement is minimised or prevented by the early removal of milk from the breasts.

• Lactation is accelerated and early frequent intake of breast milk lessens neonate weight loss.

• Attachment and bonding are enhanced at a heightened state of readiness for mother and baby.

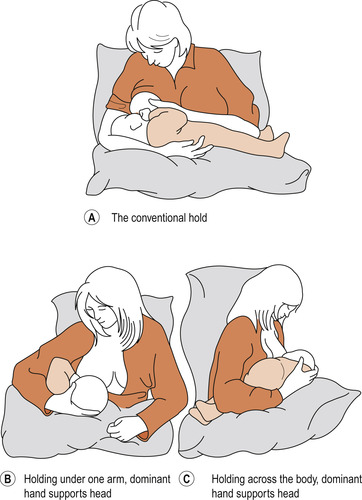

Positioning

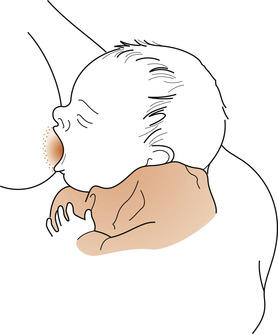

The correct positioning of the baby at the breast is essential to the success of breastfeeding and in the prevention of potential problems for mother and baby (Fig. 55.1). The midwife needs to assess the needs and preferences of the mother and to be flexible in her approach to positioning the baby. Special groups of mothers may need help with positioning such as new or first-time breastfeeding mothers, those with difficulties or previous difficulties with feeding and mothers with multiple births or special needs. Although the mother can adopt different positions to hold the baby, it is wise to offer the baby to the mother in a neutral position so that she can hold him on the arm she prefers for the first attempt (Fig. 55.2).

|

| Figure 55.1 The correct position for breastfeeding. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

|

| Figure 55.2 Ways of holding a baby during breastfeeding. |

Attachment of the baby’s mouth to the breast

Attachment to the breast is the most important aspect of breastfeeding and is essential for mothers to achieve success and prevent potential problems occurring (discussed later). Breastfeeding needs to be explained to the mother and she should be taught the basic skills involved. The mother should be given the following information:

• How to elicit the rooting reflex from the baby.

• How to offer the breast to the baby when his mouth is wide open.

• How to recognise when the baby is properly attached.

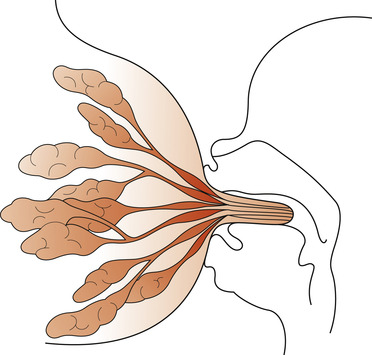

• How the milk is released by the let-down reflex and begins to flow and how the baby uses suction to hold the breast tissue in the mouth to form a teat (Fig. 55.3) and obtain the milk by the action of the tongue pressing the milk from the sinuses into the mouth. See Fig. 54.1B for up-to-date ductal anatomy of the breast.

|

| Figure 55.3 Breast tissue formed into a teat in the baby’s mouth. Please see Fig. 54.1B to review the ductal anatomy of the breast based on recent research findings. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

Four key points apply to mothers when positioning and attaching the baby to the breast:

1. The baby’s head and body should be in alignment.

2. The baby’s mouth should face the breast, with the top lip opposite the nipple.

3. The mother should hold the baby close to her.

4. If the baby is newborn, then the mother should support the baby’s whole body and not just the head and shoulders.

Key signs of good attachment

• More of the areola can be seen above the baby’s mouth than below.

• The mouth is wide open.

• The lower lip is turned outwards.

• The chin touches the breast.

Other signs of good attachment are also found during feeding. The sucking pattern is rhythmical and changes from quick short sucks to slow deep sucks. The baby will pause from time to time and then start sucking again without coaxing. The baby can be seen or heard swallowing and is relaxed, happy and releases the breast at the end of feeding. The sucking pattern of babies will now need to be revisited in light of current research findings indicating the absence of the lactiferous sinuses (reservoir for milk) which were previously believed to be behind the nipple (Geddes 2007, Ramsay et al 2005).

Nutritional aspects

The baby must be allowed to obtain both fore-milk and hind-milk from one breast before being offered the other breast. The baby should be encouraged to empty one breast before feeding from the other breast. This will ensure that the baby gets the fat-laden hind-milk and will maximise calorie intake. In addition, the breast will empty of milk and will prevent protein accumulating, which exerts a negative feedback control on milk production (Wilde et al 1995). Removing milk from the breast also removes this protein and milk production is not affected. Both breasts will continue to produce milk if the next feed is commenced on the alternate breast.

Baby-led feeding

Mothers should be assured that there is no need to know how much milk has been taken (one reason for wishing to bottle-feed). The baby will be getting sufficient nourishment if satisfied and sleeping well between feeds. In particular, mothers need to understand that breast milk is not designed to last for 4 full hours between each feed and that newborns do not differentiate night from day. At first, the mother may experience a few problems with tiredness due to frequent feeding but she should be reassured that this will settle down once the baby has developed his own circadian rhythms.

The role of lateral behavioural preferences

Human beings have at least three lateral preferences in behaviour that may influence the establishment of breastfeeding (Stables & Hewitt 1995):

Right-handed mothers may prefer to hold their baby in the left arm and, if the baby prefers to turn his head to the right, there may be a preference for feeding the baby on the left breast. The mother may feel comfortable with the baby held in her left arm, leaving her dominant right hand to manipulate the breast. The baby who prefers to turn his head to the right will automatically turn to face the left breast. The mother may perceive that feeding at the right breast is more difficult. These lateral preferences occasionally cause transient problems, usually overcome by the 3rd day as the mother and baby develop skills. However, some women who are ambivalent about breastfeeding may feel unable to continue (see Ch. 57).

Taking note of the lateral preferences, the baby may be held across the mother’s lap or tucked under her arm (see Fig. 55.3) if it is noticed that the baby consistently turns his head away from one breast (Stables & Hewitt 1995). The mother can be shown how to attach the baby to each breast using her skilful hand.

Breastfeeding problems

The following common situations and conditions often cause difficulties with breastfeeding:

• Insufficient milk supply.

• Abnormal nipples, including flat, inverted, large or long nipple.

• Sore or fissured nipples.

• Full and engorged breasts.

• Blocked ducts and mastitis.

• Breast abscess.

Other problems include breast refusal and the mother and baby with special needs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree