Breast Tumors in Children

EDI BROGI

Mass-forming breast lesions in children and adolescents are rare, and the majority are benign. The newborn breast may swell shortly after birth and during lactation because of hormones passing from the mother to the baby through the breast milk. This alteration is usually bilateral and transient. Persistent bilateral breast enlargement in a child typically indicates a hormonal imbalance due to genetic alteration or to a hormoneproducing neoplasm and should be investigated accordingly.

Pettinato et al.1 evaluated 113 breast lesions that presented as diffuse breast enlargement or a mass-forming lesion in children and adolescents 20 years old or younger at three hospitals in Minnesota and Alabama. Congenital and developmental abnormalities were found in 10 (9%) cases and consisted mainly of accessory breast tissue and supernumerary nipple in patients aged 10 to 15 years. A case of congenital hypertrophy was documented in a newborn. Inflammatory conditions, such as acute and chronic mastitis and fat necrosis, constituted 14% of all cases and also tended to occur in children aged 10 to 15 years. Nonneoplastic tumor-like lesions, including juvenile hypertrophy (20 cases) and juvenile papillomatosis (JP) (5 cases), comprised 22% of all cases. The remaining 40% of cases were primary mammary neoplasms, such as juvenile fibroadenoma (FA) (18 cases) and phyllodes tumors (2 cases), nipple duct adenoma (florid papillomatosis of the nipple) (2 cases), and lesions that are not exclusive of the breast parenchyma, including lipomas, vascular tumors (6 cases), metastatic extramammary malignant neoplasms (8 cases, all in teenage girls), rhabdomyosarcoma, and malignant lymphoma.

Most breast masses in children and adolescents develop around the time of puberty, but not all of them require immediate surgical intervention. During a 22-year period, 684 females aged 14 to 20 years were referred for evaluation of a breast mass at the University Hospital in Athens, Greece.2 Most patients (442/684; 64.6%) were managed by observation alone, and only about a third (242/684; 35.4%) underwent surgical excision. The histologic findings were benign in 97.5% of cases, including FA in 72.9%, fibrocystic changes in 24.6%, and benign cysts in 2.5%. Only six (2.5%) cases were malignant.

The most frequent breast mass lesions in female adolescents are FA and juvenile macromastia.2,3,4,5,6,7 A series from Nigeria7 documents a similar prevalence of breast lesions in African female adolescents. Gynecomastia is the most common breast mass in boys under 20 years and typically develops during puberty.

Imaging

Ecographic examination is the preferred technique for evaluation of a mass in the breast of a child or adolescent, whereas mammography has limited to no value in these age groups. A search of the ecographic studies of breast masses in patients younger than 19 years treated between 2001 and 2009 at a pediatric hospital yielded a total of 332 exams.8 Solid masses were identified in 91 (27.4%) girls. A tissue diagnosis was available for 49 (14.7%) lesions: 91% were FA, and the rest included one case each of hamartoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NLH), tubular adenoma, pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH), and lactation changes.

Risk of Subsequent Carcinoma

With the exception of JP, described later in this chapter, most benign mass-forming lesions occurring in the breast in the first two decades of life are not associated with an increased risk of developing subsequent breast carcinoma. Genetic testing for known germline mutations associated with high risk of breast carcinoma usually is not pursued in children or adolescents and should be considered only after the patient reaches the age of consent. At present, no other parameters are available that could help identify young individuals at high risk of developing breast carcinoma. A study by Wu et al.9 found lower global methylation levels in white blood cells of girls aged between 6 and 17 years with a strong family history of breast carcinoma than in those without, suggesting that the effect of environmental factors resulting in epigenetic alterations of gene expression may have an impact quite early in life.

JUVENILE PAPILLOMATOSIS

Clinical Presentation

Age and Gender

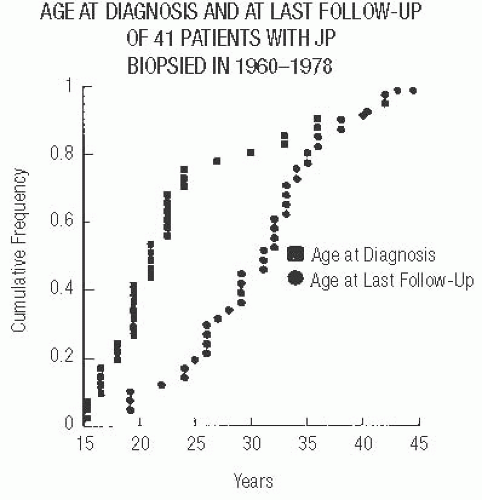

The localized benign proliferative lesion known as JP usually occurs in women younger than 30 years. At the time of diagnosis, two-thirds of the patients are younger than 25 (Fig. 37.1). JP is uncommon prior to puberty and after the age of 40.10,11 Rare cases of JP in infants with neurofibromatosis are not fully convincing.12,13,14 On the basis of the

illustrations provided, the lesion described by Tan et al.12 appears to have been papillary duct hyperplasia rather than JP. Although it had “extensive microcysts” grossly, this feature is not evident in the published histologic picture. The cystic expansion of ducts that can occur in juvenile papillary duct hyperplasia lacks apocrine metaplasia and other features that are conspicuous in JP. Pacilli et al.13 described a cystic mass “containing whitish milky fluid attached to the under-surface of the nipple” in a 13-month-old infant. The lesion illustrated appears to be stasis of secretion in dilated ducts, possibly a galactocele, in a fibrotic nodule. A report by Rice14 describes two male infants with lesions purported to be JP. However, the single histologic picture provided shows only cystic duct ectasia without the characteristic proliferative changes of JP, leaving the diagnosis of JP in doubt.

illustrations provided, the lesion described by Tan et al.12 appears to have been papillary duct hyperplasia rather than JP. Although it had “extensive microcysts” grossly, this feature is not evident in the published histologic picture. The cystic expansion of ducts that can occur in juvenile papillary duct hyperplasia lacks apocrine metaplasia and other features that are conspicuous in JP. Pacilli et al.13 described a cystic mass “containing whitish milky fluid attached to the under-surface of the nipple” in a 13-month-old infant. The lesion illustrated appears to be stasis of secretion in dilated ducts, possibly a galactocele, in a fibrotic nodule. A report by Rice14 describes two male infants with lesions purported to be JP. However, the single histologic picture provided shows only cystic duct ectasia without the characteristic proliferative changes of JP, leaving the diagnosis of JP in doubt.

No clinical data on the prevalence of JP are available. However, JP was found in 1 of 519 forensic autopsies of females 14 years or older performed over a 5-year interval by a state medical examiner.15 Because JP was not formally characterized before 1980, it was not recognized as a specific lesion in earlier reports, which, in retrospect, described this condition.16 Only few series of JP have been reported, and case reports are sporadic. Rare instances of JP have been described in boys,17,18 including a 17-year-old boy who presented with 2- to 3-month-long history of intermittent nipple discharge,18 but images of the histologic findings were not provided.

Presenting Symptoms

The typical clinical finding is a solitary, firm, discrete unilateral tumor that clinically mimics a FA. Very rarely the presenting symptoms of JP include pain11 and/or nipple discharge, which rarely can be bloody.11,18 Bilateral JP may be synchronous or metachronous. Very rare instances of multifocal tumors in one breast have been reported. A separate coexisting FA is not unusual.

It is not unusual for patients with JP to have had one or more biopsies of the ipsilateral or contralateral breast prior to the diagnosis of JP. Concurrent contralateral biopsies and subsequent biopsies of either breast have also been reported.19 Most prior biopsies have been for FA or benign proliferative lesions other than JP. Similar findings have been reported in most concurrent contralateral biopsies, but rare patients have had carcinoma in the opposite breast.

Imaging

Few descriptions of the mammographic findings in JP are available because mammography is not usually performed preoperatively in these young women. The mammograms reveal a localized area of increased density with a border that is generally not as well defined as that of a FA11,20 (Fig. 37.2). The sonographic appearance of JP is that of an ill-defined or discrete inhomogeneous, hypoechoic mass with multiple cysts.20,21,22 The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings of JP in female patients 29, 24, and 13 years of age23,24 have been reported. The lesions were mass forming with a complex solid and cystic pattern, multiple small cysts on T2-weighted images and continuous enhancement on kinetic evaluation.

Family History of Breast Carcinoma

At the time of diagnosis, patients with JP report a frequency of positive family history for breast carcinoma that is similar to that of patients who have mammary carcinoma.25,26 With

further follow-up, the frequency of positive family history exceeds 50%.19 Because of the youth of JP patients, the high frequency of breast carcinoma in these families is particularly remarkable, since it may be assumed that female relatives of patients with JP tend to be younger than comparable relatives of breast carcinoma patients.

further follow-up, the frequency of positive family history exceeds 50%.19 Because of the youth of JP patients, the high frequency of breast carcinoma in these families is particularly remarkable, since it may be assumed that female relatives of patients with JP tend to be younger than comparable relatives of breast carcinoma patients.

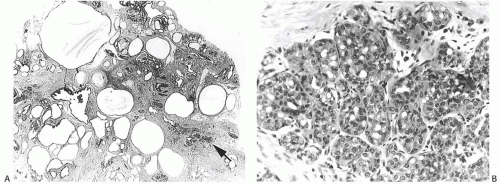

FIG. 37.2. Juvenile papillomatosis, mammography. The lesion forms the oval mass indicated by an arrow in this xeromammogram. |

About 10% to 15% of patients with JP also have breast carcinoma.11,19,26 Women with JP and coexistent carcinoma are usually in the upper quartile of the age distribution of JP. Virtually all of these women have had a positive family history for breast carcinoma, usually affecting their mother or a maternal aunt.19,26 Breast carcinoma and other benign breast tumors, including JP, have only rarely been seen in the sisters of JP patients. The female relatives of patients with JP most likely to be affected by breast carcinoma are their mothers and maternal aunts. JP is not associated with an increased frequency of breast carcinoma in paternal female relatives, and there is no association with any type of nonmammary neoplasm. Given the rarity of JP in boys, it is unclear whether this lesion in males carries the same high association with familial breast carcinoma.

Genetic Alterations

Gross Pathology

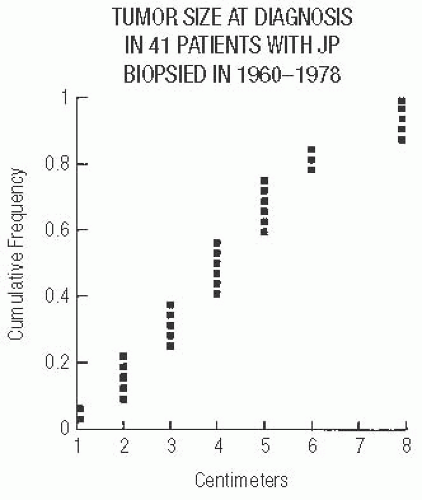

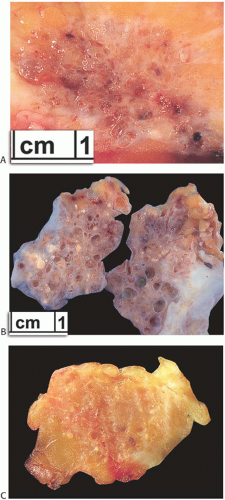

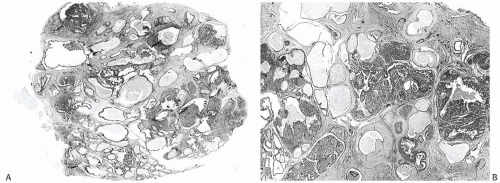

The excised tumor is a firm discrete mass that appears to be distinct from the surrounding breast on the cut surface but lacks the sharply circumscribed border typical of a FA. The lesions measure 1 to 8 cm in diameter and average 4 cm (Fig. 37.3). The most prominent gross feature is multiple cysts ranging from 1 mm to 2 cm in size. The larger cysts tend to be located in the center of the lesion. The intervening tissue often has white or yellow flecks that resemble comedonecrosis (Fig. 37.4).

Microscopic Pathology

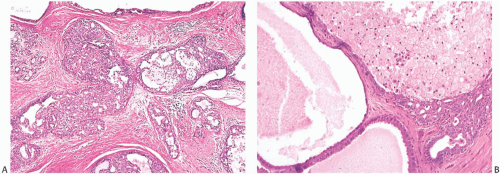

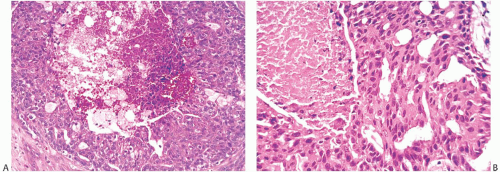

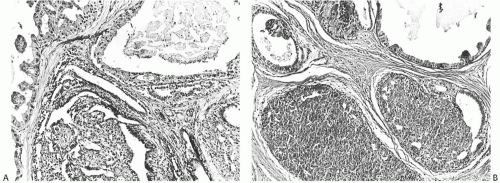

Histologic examination reveals a spectrum of benign proliferative changes that are present in varying proportions in individual cases. The alterations tend to be localized. Cysts and duct hyperplasia are constant features (Figs. 37.5, 37.6, 37.7 to 37.7). The epithelium of cysts and duct hyperplasia frequently exhibits apocrine metaplasia (Fig. 37.8), which may be flat or papillary. Stasis of secretion in cysts and ducts manifested by collections of lipid-laden histiocytes is seen in most specimens (Fig. 37.9). These reactive alterations correspond to the yellow and white flecks observed grossly. Sclerosing adenosis (SA), lobular hyperplasia, and fibroadenomatoid hyperplasia are variably present.

In most cases, the ductal proliferative changes consist of usual hyperplasia. Sometimes ductal hyperplasia is accompanied by sclerosis that produces a radial scar pattern. Atypical changes in the ductal hyperplasia include cribriform or micropapillary growth patterns and intraductal necrosis (Fig. 37.10). In one series, there was significant atypia in 40% and intraductal necrosis in 15% of JP cases.19 The stroma admixed with the epithelial alterations of JP tends to be dense and fibrous with a resulting “Swiss cheese” appearance on gross examination.

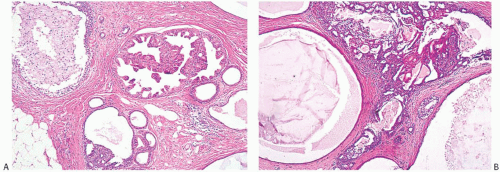

FIG. 37.5. Juvenile papillomatosis. A,B: Whole-mount photographs of histologic sections of two lesions. Papillary duct hyperplasia is more pronounced in (B). |

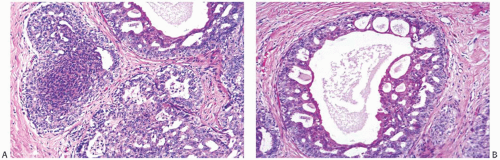

FIG. 37.6. Juvenile papillomatosis, cysts and duct hyperplasia. A,B: Two microscopic fields showing patterns of duct hyperplasia characteristic of JP. |

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of JP should not be used for lesions that consist only of cysts, cystic papillomas, or papillomas. For example, illustrations of the lesion reported as “juvenile papillomatosis” by Talisman et al.27 show cysts and intracystic papillomas rather than the typical features of JP. Specimens showing only a solitary papilloma, multiple dispersed papillomas, and sclerosing papillomas with a radial scar configuration

included in the group of lesions termed “papillary duct hyperplasia” are not part of the spectrum of JP.28,29,30,31

included in the group of lesions termed “papillary duct hyperplasia” are not part of the spectrum of JP.28,29,30,31

FIG. 37.7. Juvenile papillomatosis, duct hyperplasia. A,B: Solid and cribriform duct hyperplasia with apocrine metaplasia. This appearance is frequently found in JP. |

FIG. 37.8. Juvenile papillomatosis, apocrine metaplasia. A: Papillary apocrine metaplasia. B: A pocrine metaplasia of cyst epithelium and in papillary duct hyperplasia. |

Breast Carcinomas Associated with JP

The types of breast carcinoma associated with JP include ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), infiltrating duct carcinoma, infiltrating lobular carcinoma, and secretory (juvenile) carcinoma. Most patients have had carcinoma and JP diagnosed concurrently19,26 (Figs. 37.11 and 37.12), typically at an age older than adolescence. With few exceptions, the carcinoma occurred within JP and appeared to arise from it. One exceptional patient had JP in one breast and concurrent contralateral secretory carcinoma not associated with JP.

Risk of Subsequent Breast Carcinoma

The risk of subsequent carcinoma in patients who had JP excised previously has been evaluated in one series.19 A review of 41 patients with at least 10 years of followup after the diagnosis of JP (median 14 years) found that 4 patients (10%) subsequently developed breast carcinoma after an interval of 5 to 15 years19 (Fig. 37.13). These patients were 25 to 42 years old when JP was diagnosed, and thus all were older than the mean age for JP. Three of the patients had multifocal or bilateral JP. DCIS was diagnosed in two of these women, and a third had DCIS with microinvasion. The fourth patient had unilateral JP at the age of 29. Thirteen years later, recurrent ipsilateral JP was found, and a concurrent biopsy of the contralateral breast revealed DCIS that was not associated with JP.

Treatment and Prognosis

JP is rarely considered as the preoperative diagnosis. In most instances, the clinical findings suggest a FA. Consequently, excisional biopsy is often performed with little margin. Incomplete excision probably predisposes to local recurrence, but this may occur even when the margins appear

to be adequate histologically. It is the opinion of the Senior Editor that reexcision of the biopsy site would be prudent if the lesion has not been completely excised, and the reexcision will not cause a significant cosmetic defect. Reexcision is also recommended for incompletely excised JP with atypical hyperplasia, or if the lesion is a recurrence of JP and the margin remains involved.

to be adequate histologically. It is the opinion of the Senior Editor that reexcision of the biopsy site would be prudent if the lesion has not been completely excised, and the reexcision will not cause a significant cosmetic defect. Reexcision is also recommended for incompletely excised JP with atypical hyperplasia, or if the lesion is a recurrence of JP and the margin remains involved.

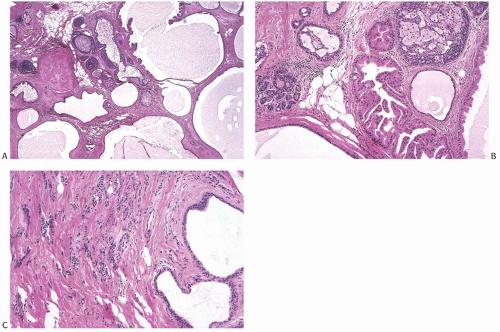

FIG. 37.12. Invasive lobular carcinoma in juvenile papillomatosis. The specimen is from a 46-year-old woman. A,B: Cysts, duct hyperplasia, and apocrine metaplasia in JP. C: Invasive lobular carcinoma adjacent to cysts in the tumor shown in (A) and (B). |

Unless carcinoma is found in the tumor, no treatment is necessary after complete excisional biopsy. Follow-up examinations should be scheduled annually or more frequently for patients who have multifocal, bilateral, or recurrent JP, and if there are other risk factors such as a positive family history for breast carcinoma. Mammography should be employed judiciously during follow-up, especially for patients younger than 35 years of age, to minimize radiation exposure and because its sensitivity is limited in this age group. Ultrasonography is the preferred method for evaluation of breast masses in this young age group. MRI

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree