Patient Story

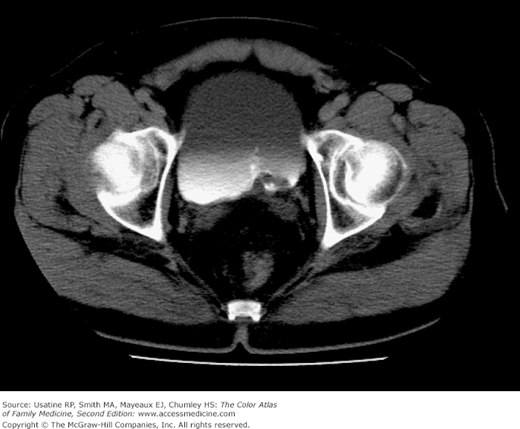

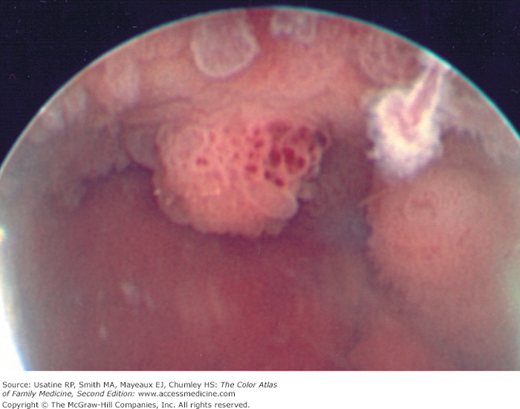

A 68-year-old man, who is a retired painter and in good health, comes to the office at the insistence of his wife. He reports that his urinary stream is smaller and he has occasional dysuria. He has no major medical problems, although he continues to smoke one pack of cigarettes per day. His urinalysis in the office shows microscopic hematuria and an irregular mass is seen in the bladder on CT scan (Figure 72-1). Cystoscopy shows a bladder tumor (Figure 72-2). Complete endoscopic resection is performed and confirms transitional cell carcinoma.

Figure 72-2

Cystoscopic view of the transitional cell carcinoma in the man in Figure 72-1. (Courtesy of Carlos Enrique Bermejo, MD.)

Introduction

Epidemiology

- In 2008, there were approximately 398,329 men and 139,099 women alive in the United States who had a history of cancer of the urinary bladder.1

- Almost 70,000 new cases (52,020 men and 17,230 women) were diagnosed and approximately 14,990 deaths occurred from bladder cancer in 2011.1 Mean age at diagnosis is 73 years.

- The age-adjusted incidence rate (based on 2004 to 2008 data) was 21.1 per 100,000 men and women per year with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 4:1. Among men, bladder cancer is more prevalent in whites than in blacks or Hispanics (ratio of 2:1) and more prevalent in whites than in Asian/Pacific Islander or American Indian/Alaska Natives (ratio 2.4:1); for white women, incidence rates are also higher but the differences are not as great.1

Etiology and Pathophysiology

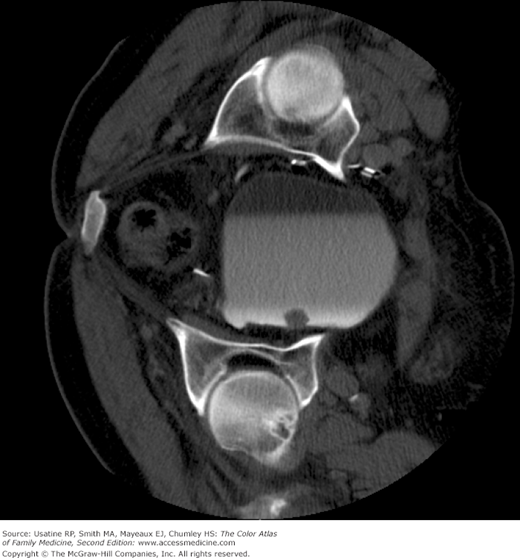

- Ninety percent to 95% are transitional cell cancers and the remainder are nonurothelial neoplasms, including primarily squamous cell, adenocarcinoma, and small cell carcinoma2,3 (Figures 72-1, 72-2, and 72-4). Rare forms include nonepithelial neoplasms (approximately 1%), including benign tumors, such as hemangiomas or lipomas, and malignant tumors, such as angiosarcomas.3

- Transitional cells line the urinary tract from the renal pelvis to the proximal two-thirds of the urethra. Ninety percent of transitional cell tumors develop in the bladder and the others develop in the renal pelvis, ureters, or urethra.2

- Most tumors are superficial (75% to 85%).4 At diagnosis, approximately 51% are in situ and 35% are localized (confined to primary site) with an additional 7% of cases having regional spread and 4% having distant metastases at diagnosis (3% unknown).2

- Multiple tumors are seen in 30% of cases.4

- Bladder tumor cells are also graded based on their appearance and behavior into well differentiated or low grade (grade 1), moderately well differentiated or moderate grade (grade 2), and poorly differentiated or high grade (grade 3).

- The most common sites of hematogenous spread are lung, bone, liver, and brain. Superficial lesions do not metastasize until they invade deeply and may remain indolent for years.2

Risk Factors

- Risk factors include smoking (odds ratio increased by 3- to 4-fold; 50% attributable risk) and exposure to pelvic radiation,5 the drugs phenacetin and chlornaphazine, external-beam radiation, and chronic infection, including Schistosoma haematobium and genitourinary tuberculosis.2,3

- There is an increased risk in certain occupations, particularly those involving exposure to metals (e.g., aluminum), paint and solvents, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, diesel engine emissions, aniline dyes (e.g., workers in chemical plants exposed to benzidine or o-toluidine),2 and textiles.6

- An increased risk was also seen with drinking tap water (odds ratio [OR] for >2 L/day vs. ≤0.5 L/day was 1.46 [1.20 to 1.78]), with a higher risk among men (OR = 1.50, 1.21 to 1.88).7

- Familial cases indicate a genetic predisposition.8

Diagnosis

- Hematuria in 80% to 90%; with microscopic hematuria approximately 2% have bladder cancer and with gross hematuria approximately 20% have bladder cancer.3

- Irritative symptoms (i.e., dysuria, frequency) are the most common presentation.

- Obstructive symptoms may occur if the tumor is located near the urethra or bladder neck.

- Urine microscopy and culture to rule out bladder infection.3

- Urine cytology (high specificity [90% to 95%] but low sensitivity [23% to 60%]), CT scan of the pelvis (Figures 72-1, 72-3, and 72-4) or intravenous urography (IVU), and cystoscopy with biopsy (Figure 72-2) comprise the basic work-up.2 Fluorescence cystoscopy (use of photosensitizer instilled into the bladder, can enhance detection of flat neoplastic lesions like carcinoma in situ (CIS).4 When CIS is found in a cystectomy specimen, 9% to 13% of patients have upper urinary tract disease.4

- Bladder wash cytology during cystoscopy detects most CIS.3

- A complete blood count, blood chemistry tests (including alkaline phosphatase tests), liver function tests, CT or MRI of the chest or abdomen and a bone scan may be needed for suspected metastatic disease.2,3 Bone scanning may be limited to patients with bone pain and/or elevated levels of serum alkaline phosphatase.4

- Tumor markers such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis and nuclear matrix protein (NMP) 22 identify changes in cells in the urine and are more sensitive than urine cytology for low-grade tumors with equivalent sensitivity for high-grade tumors and CIS.9 As specificity is low, tumor markers should not be used for diagnosis.

- For pretreatment staging of invasive bladder cancer, the American College of Radiology (ACR) recommends a chest X-ray (with chest CT if equivocal), CT of the abdomen and pelvis (without and with contrast) or MRI of the pelvis (especially in cases where patients are unable to undergo contrast injection), and possibly IVU; contrast-enhanced MRI is preferred over CT for local staging.4 SOR C

- The European Association of Urology (EAU) recommends multidetector-row CT (MDCT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis as the optimal form of staging for patients with confirmed muscle-invasive bladder cancer, including MDCT urography for examination of the upper urinary tracts.9 If MDCT is not available, alternatives are excretory urography and a chest X-ray. SOR B

- EAU recommends renal and bladder ultrasonography, and IVU or CT prior to transurethral resection for presumed invasive bladder cancer.10 SOR B ACR agrees that ultrasound is useful for local tumor staging.4 For patients with verified invasive bladder cancer, EAU recommends either MRI with fast dynamic contrast-enhancement or MDCT with contrast enhancement for patients considered suitable for radical treatment. SOR B

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree