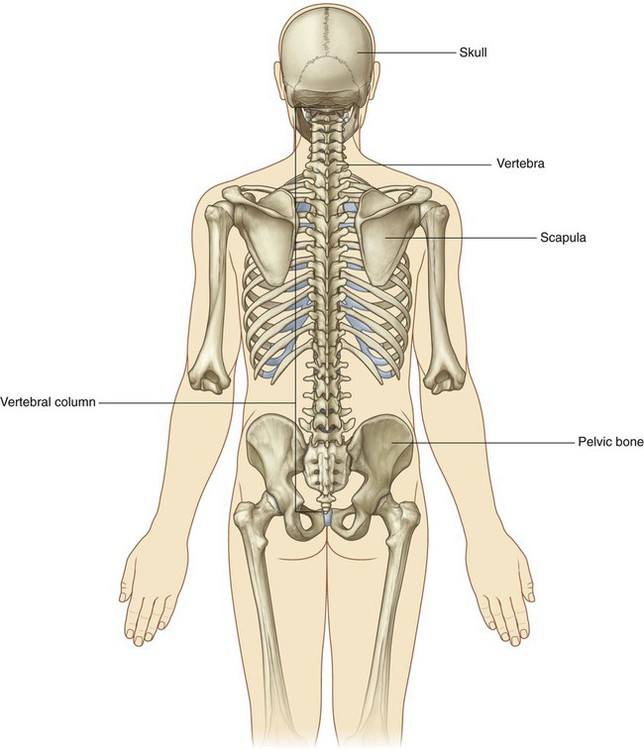

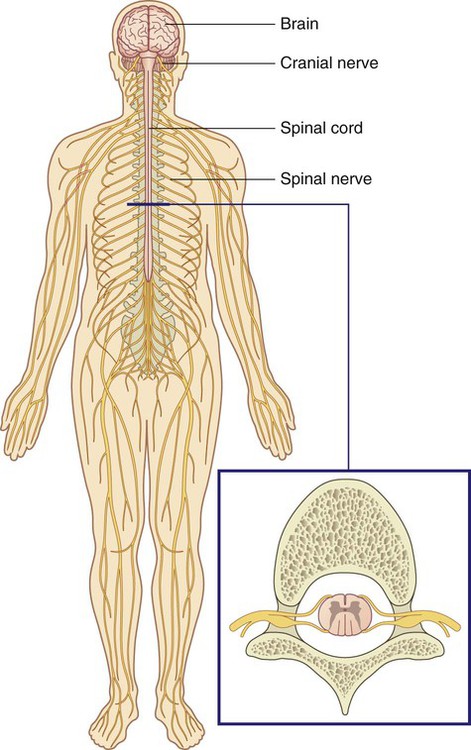

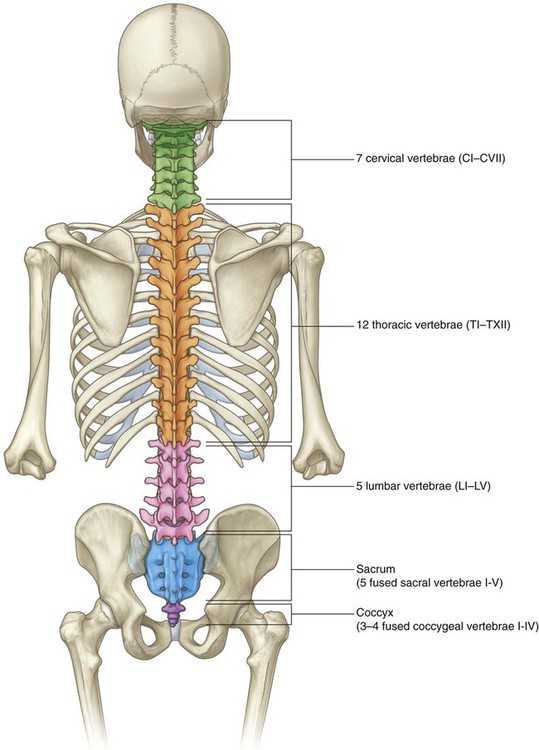

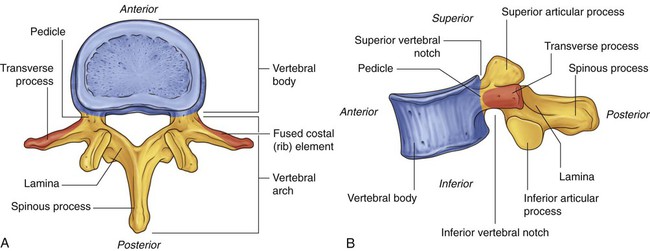

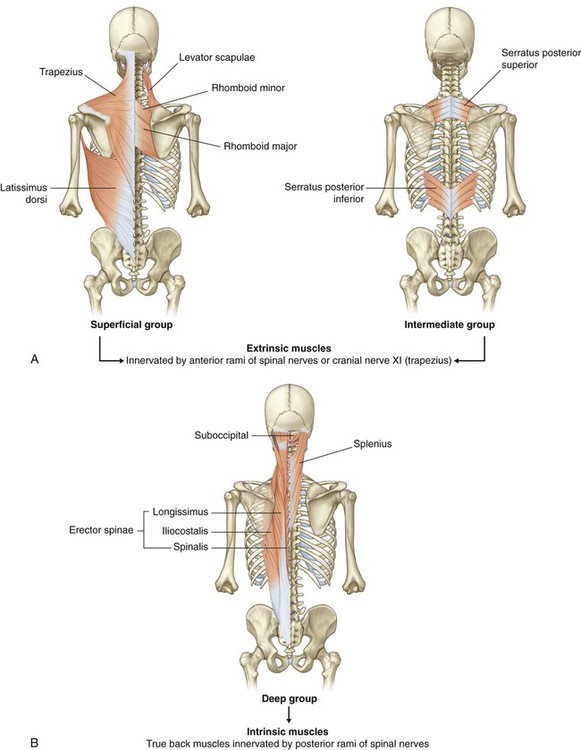

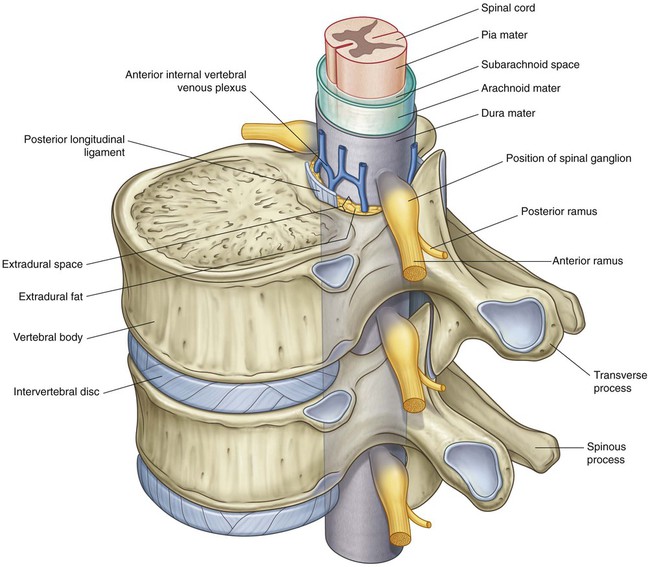

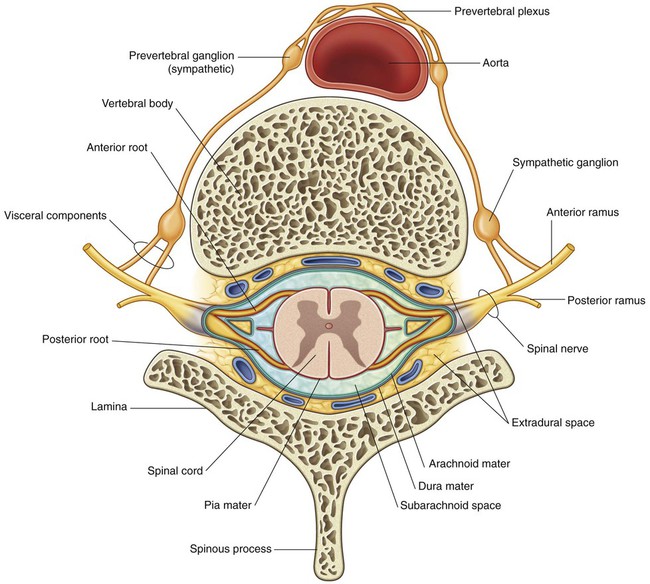

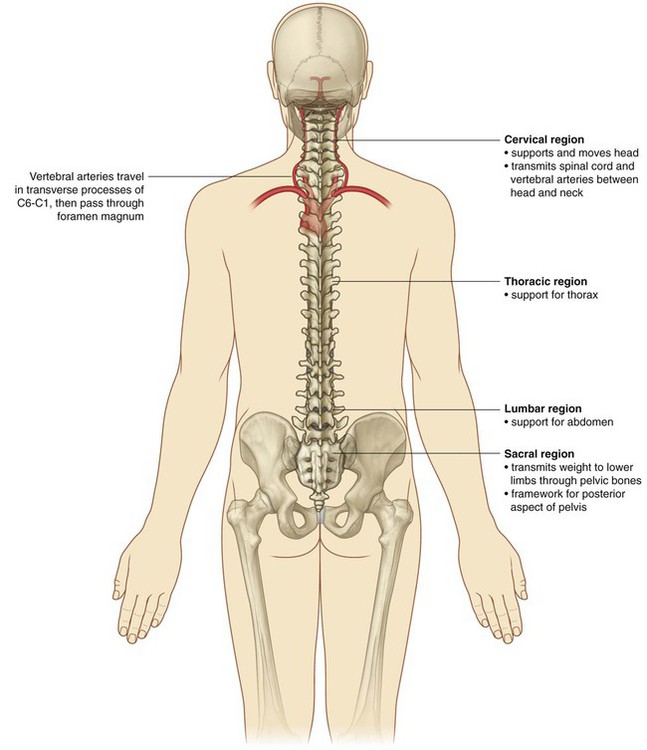

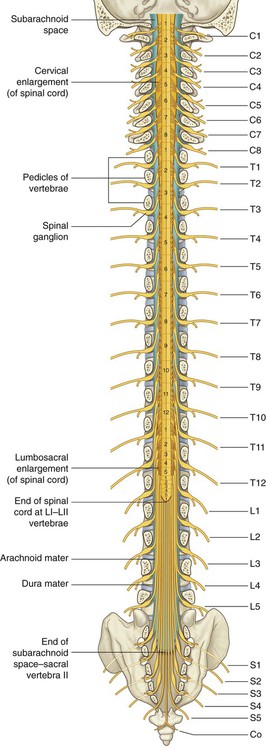

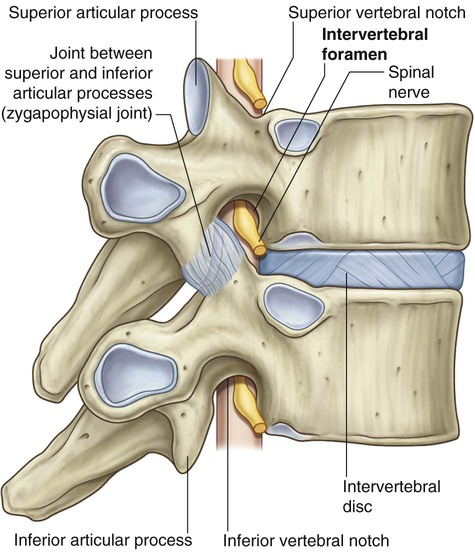

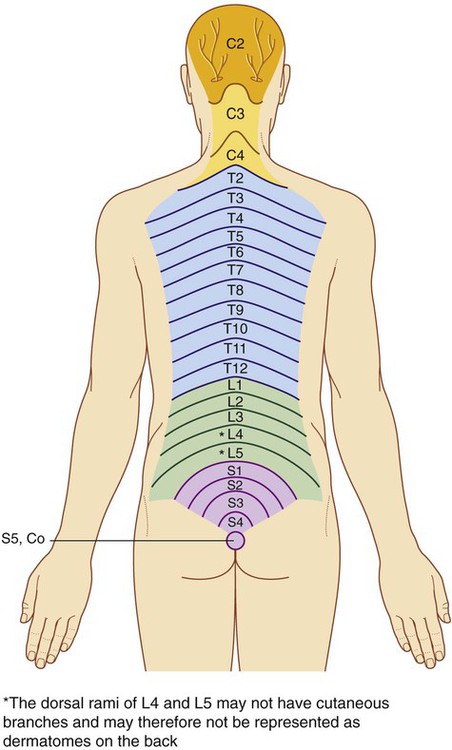

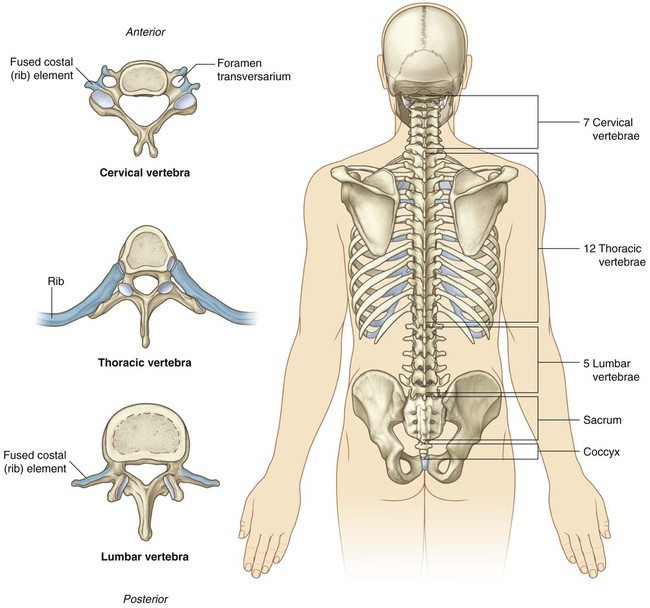

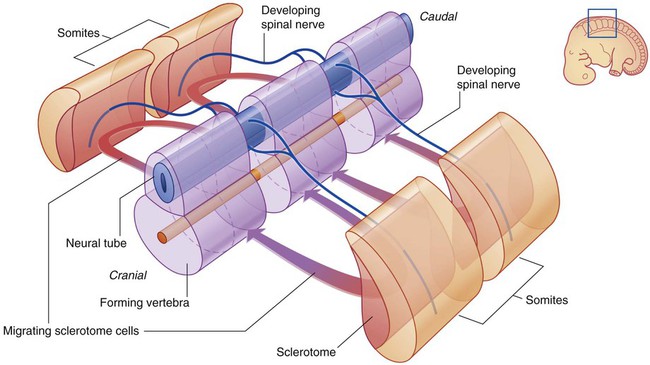

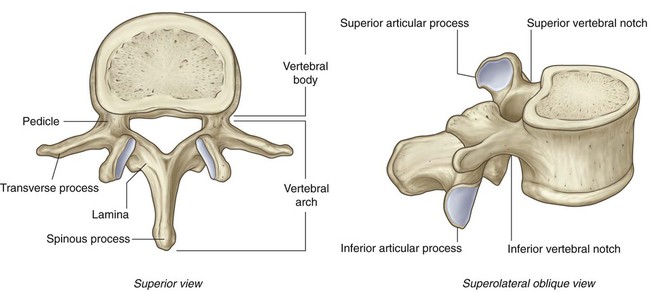

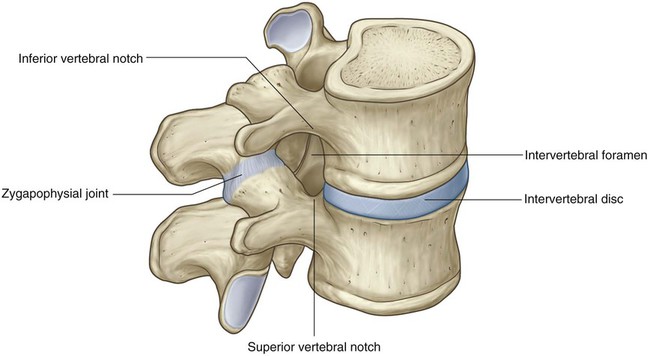

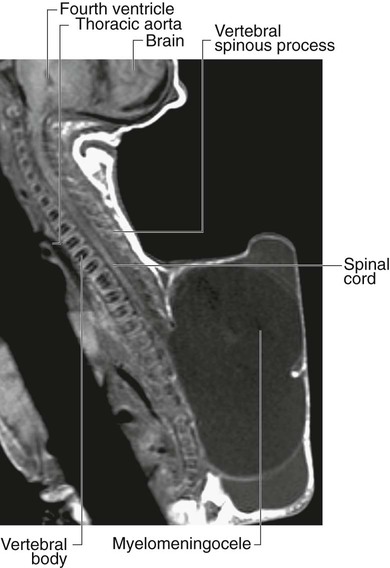

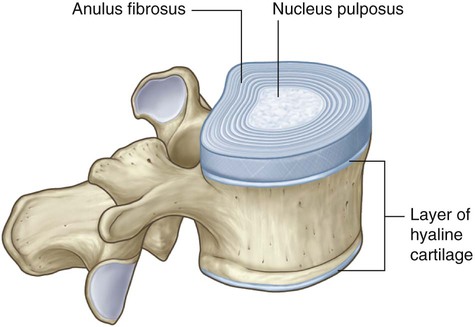

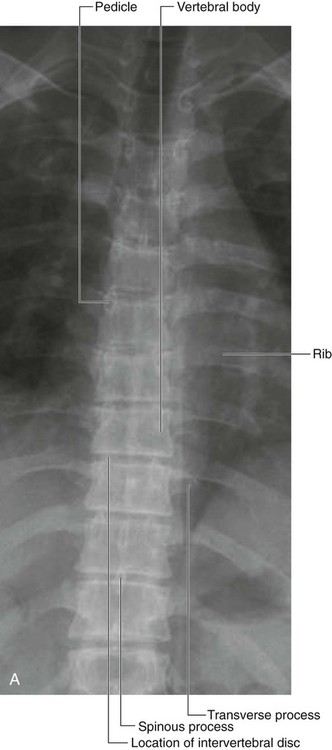

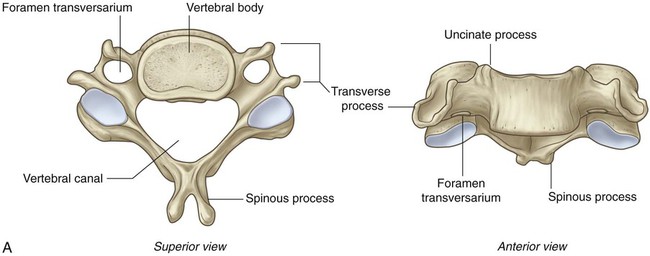

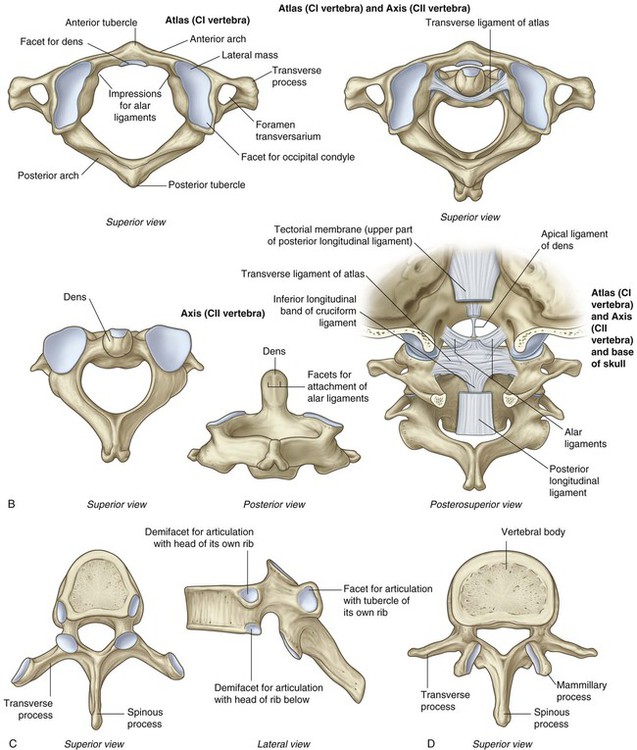

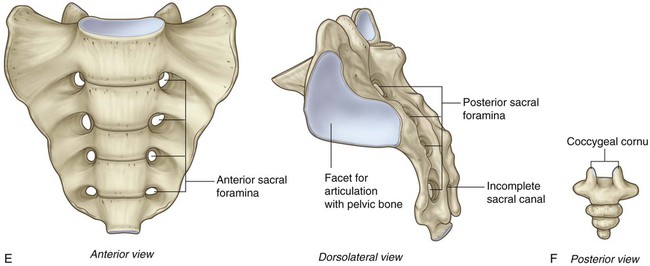

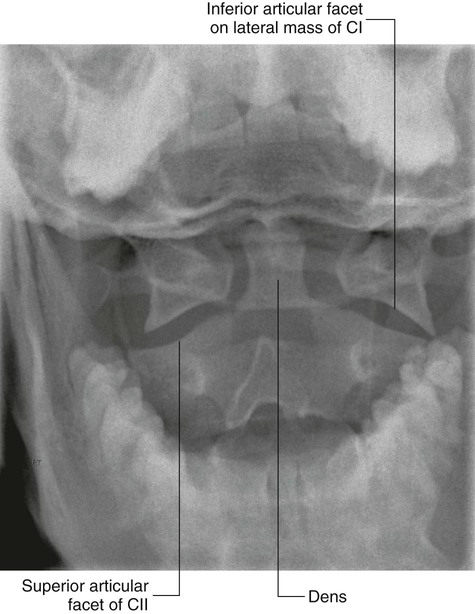

The back consists of the posterior aspect of the body and provides the musculoskeletal axis of support for the trunk. Bony elements consist mainly of the vertebrae, although proximal elements of the ribs, superior aspects of the pelvic bones, and posterior basal regions of the skull contribute to the back’s skeletal framework (Fig. 2.1). The skeletal and muscular elements of the back support the body’s weight, transmit forces through the pelvis to the lower limbs, carry and position the head, and brace and help maneuver the upper limbs. The vertebral column is positioned posteriorly in the body at the midline. When viewed laterally, it has a number of curvatures (Fig. 2.2): Muscles of the back consist of extrinsic and intrinsic groups: In the cervical region, the first two vertebrae and associated muscles are specifically modified to support and position the head. The head flexes and extends, in the nodding motion, on vertebra CI, and rotation of the head occurs as vertebra CI moves on vertebra CII (Fig. 2.3). The major bones of the back are the 33 vertebrae (Fig. 2.5). The number and specific characteristics of the vertebrae vary depending on the body region with which they are associated. There are seven cervical, twelve thoracic, five lumbar, five sacral, and three to four coccygeal vertebrae. The sacral vertebrae fuse into a single bony element, the sacrum. The coccygeal vertebrae are rudimentary in structure, vary in number from three to four, and often fuse into a single coccyx. A typical vertebra consists of a vertebral body and a vertebral arch (Fig. 2.6). The vertebral arch of a typical vertebra has a number of characteristic projections, which serve as: A spinous process projects posteriorly and generally inferiorly from the roof of the vertebral arch. The spinal cord lies within a bony canal formed by adjacent vertebrae and soft tissue elements (the vertebral canal) (Fig. 2.8): The 31 pairs of spinal nerves are segmental in distribution and emerge from the vertebral canal between the pedicles of adjacent vertebrae. There are eight pairs of cervical nerves (C1 to C8), twelve thoracic (T1 to T12), five lumbar (L1 to L5), five sacral (S1 to S5), and one coccygeal (Co). Each nerve is attached to the spinal cord by a posterior root and an anterior root (Fig. 2.9). After exiting the vertebral canal, each spinal nerve branches into: Cervical regions of the back constitute the skeletal and much of the muscular framework of the neck, which in turn supports and moves the head (Fig. 2.10). The different regions of the vertebral column contribute to the skeletal framework of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis (Fig. 2.10). In addition to providing support for each of these parts of the body, the vertebrae provide attachments for muscles and fascia, and articulation sites for other bones. The anterior rami of spinal nerves associated with the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis pass into these parts of the body from the back. During development, the vertebral column grows much faster than the spinal cord. As a result, the spinal cord does not extend the entire length of the vertebral canal (Fig. 2.11). Each spinal nerve exits the vertebral canal laterally through an intervertebral foramen (Fig. 2.12). The foramen is formed between adjacent vertebral arches and is closely related to intervertebral joints: Posterior branches of spinal nerves innervate the intrinsic muscles of the back and adjacent skin. The cutaneous distribution of these posterior rami extends into the gluteal region of the lower limb and the posterior aspect of the head. Parts of dermatomes innervated by the posterior rami of spinal nerves are shown in Fig. 2.13. There are approximately 33 vertebrae, which are subdivided into five groups based on morphology and location (Fig. 2.14): In the embryo, the vertebrae are formed intersegmentally from cells called sclerotomes, which originate from adjacent somites (Fig. 2.18). Each vertebra is derived from the cranial parts of the two somites below, one on each side, and the caudal parts of the two somites above. The spinal nerves develop segmentally and pass between the forming vertebrae. A typical vertebra consists of a vertebral body and a posterior vertebral arch (Fig. 2.19). Extending from the vertebral arch are a number of processes for muscle attachment and articulation with adjacent bone. The vertebral arch forms the lateral and posterior parts of the vertebral foramen. The vertebral arch of each vertebra consists of pedicles and laminae (Fig. 2.19): Also projecting from the region where the pedicles join the laminae are superior and inferior articular processes (Fig. 2.19), which articulate with the inferior and superior articular processes, respectively, of adjacent vertebrae. The seven cervical vertebrae are characterized by their small size and by the presence of a foramen in each transverse process. A typical cervical vertebra has the following features (Fig. 2.20A): Vertebra CI (the atlas) articulates with the head (Fig. 2.21). Its major distinguishing feature is that it lacks a vertebral body (Fig. 2.20B). In fact, the vertebral body of CI fuses onto the body of CII during development to become the dens of CII. As a result, there is no intervertebral disc between CI and CII. When viewed from above, the atlas is ring shaped and composed of two lateral masses interconnected by an anterior arch and a posterior arch. The atlanto-occipital joint allows the head to nod up and down on the vertebral column. The axis is characterized by the large tooth-like dens, which extends superiorly from the vertebral body (Figs. 2.20B and 2.21). The anterior surface of the dens has an oval facet for articulation with the anterior arch of the atlas. The twelve thoracic vertebrae are all characterized by their articulation with ribs. A typical thoracic vertebra has two partial facets (superior and inferior costal facets) on each side of the vertebral body for articulation with the head of its own rib and the head of the rib below (Fig. 2.20C). The superior costal facet is much larger than the inferior costal facet. The five lumbar vertebrae are distinguished from vertebrae in other regions by their large size (Fig. 2.20D). Also, they lack facets for articulation with ribs. The transverse processes are generally thin and long, with the exception of those on vertebra LV, which are massive and somewhat cone shaped for the attachment of iliolumbar ligaments to connect the transverse processes to the pelvic bones. The sacrum is a single bone that represents the five fused sacral vertebrae (Fig. 2.20E). It is triangular in shape with the apex pointed inferiorly, and is curved so that it has a concave anterior surface and a correspondingly convex posterior surface. It articulates above with vertebra LV and below with the coccyx. It has two large L-shaped facets, one on each lateral surface, for articulation with the pelvic bones. The posterior wall of the vertebral canal may be incomplete near the inferior end of the sacrum. Intervertebral foramina are formed on each side between adjacent parts of vertebrae and associated intervertebral discs (Fig. 2.22). The foramina allow structures, such as spinal nerves and blood vessels, to pass in and out of the vertebral canal. In most regions of the vertebral column, the laminae and spinous processes of adjacent vertebrae overlap to form a reasonably complete bony dorsal wall for the vertebral canal. However, in the lumbar region, large gaps exist between the posterior components of adjacent vertebral arches (Fig. 2.23). These gaps between adjacent laminae and spinous processes become increasingly wide from vertebra LI to vertebra LV. The spaces can be widened further by flexion of the vertebral column. These gaps allow relatively easy access to the vertebral canal for clinical procedures.

Back

Conceptual overview

General description

Functions

Support

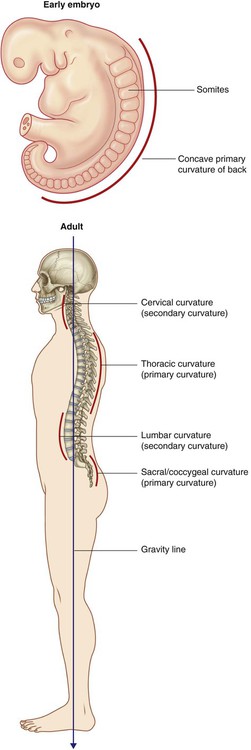

The primary curvature of the vertebral column is concave anteriorly, reflecting the original shape of the embryo, and is retained in the thoracic and sacral regions in adults.

The primary curvature of the vertebral column is concave anteriorly, reflecting the original shape of the embryo, and is retained in the thoracic and sacral regions in adults.

Secondary curvatures, which are concave posteriorly, form in the cervical and lumbar regions and bring the center of gravity into a vertical line, which allows the body’s weight to be balanced on the vertebral column in a way that expends the least amount of muscular energy to maintain an upright bipedal stance.

Secondary curvatures, which are concave posteriorly, form in the cervical and lumbar regions and bring the center of gravity into a vertical line, which allows the body’s weight to be balanced on the vertebral column in a way that expends the least amount of muscular energy to maintain an upright bipedal stance.

Movement

The extrinsic muscles of the back move the upper limbs and the ribs.

The extrinsic muscles of the back move the upper limbs and the ribs.

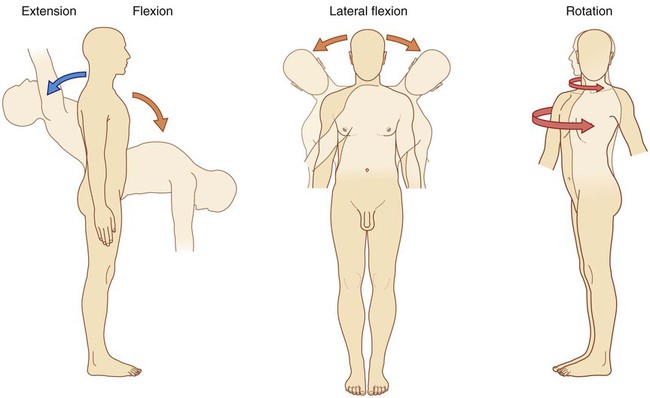

The intrinsic muscles of the back maintain posture and move the vertebral column; these movements include flexion (anterior bending), extension, lateral flexion, and rotation (Fig. 2.3).

The intrinsic muscles of the back maintain posture and move the vertebral column; these movements include flexion (anterior bending), extension, lateral flexion, and rotation (Fig. 2.3).

Component parts

Bones

Typical vertebra

Vertebral canal

The anterior wall is formed by the vertebral bodies of the vertebrae, intervertebral discs, and associated ligaments.

The anterior wall is formed by the vertebral bodies of the vertebrae, intervertebral discs, and associated ligaments.

The lateral walls and roof are formed by the vertebral arches and ligaments.

The lateral walls and roof are formed by the vertebral arches and ligaments.

The pia mater is the innermost membrane and is intimately associated with the surface of the spinal cord.

The pia mater is the innermost membrane and is intimately associated with the surface of the spinal cord.

The second membrane, the arachnoid mater, is separated from the pia by the subarachnoid space, which contains cerebrospinal fluid.

The second membrane, the arachnoid mater, is separated from the pia by the subarachnoid space, which contains cerebrospinal fluid.

The thickest and most external of the membranes, the dura mater, lies directly against, but is not attached to, the arachnoid mater.

The thickest and most external of the membranes, the dura mater, lies directly against, but is not attached to, the arachnoid mater.

Spinal nerves

a posterior ramus—collectively, the small posterior rami innervate the back; and

a posterior ramus—collectively, the small posterior rami innervate the back; and

an anterior ramus—the much larger anterior rami innervate most other regions of the body except the head, which is innervated predominantly, but not exclusively, by cranial nerves.

an anterior ramus—the much larger anterior rami innervate most other regions of the body except the head, which is innervated predominantly, but not exclusively, by cranial nerves.

Relationship to other regions

Head

Thorax, abdomen, and pelvis

Key features

Long vertebral column and short spinal cord

Intervertebral foramina and spinal nerves

The superior and inferior margins are formed by notches in adjacent pedicles.

The superior and inferior margins are formed by notches in adjacent pedicles.

The posterior margin is formed by the articular processes of the vertebral arches and the associated joint.

The posterior margin is formed by the articular processes of the vertebral arches and the associated joint.

The anterior border is formed by the intervertebral disc between the vertebral bodies of the adjacent vertebrae.

The anterior border is formed by the intervertebral disc between the vertebral bodies of the adjacent vertebrae.

Innervation of the back

Regional anatomy

Skeletal framework

Vertebrae

The seven cervical vertebrae between the thorax and skull are characterized mainly by their small size and the presence of a foramen in each transverse process (Figs. 2.14 and 2.15).

The seven cervical vertebrae between the thorax and skull are characterized mainly by their small size and the presence of a foramen in each transverse process (Figs. 2.14 and 2.15).

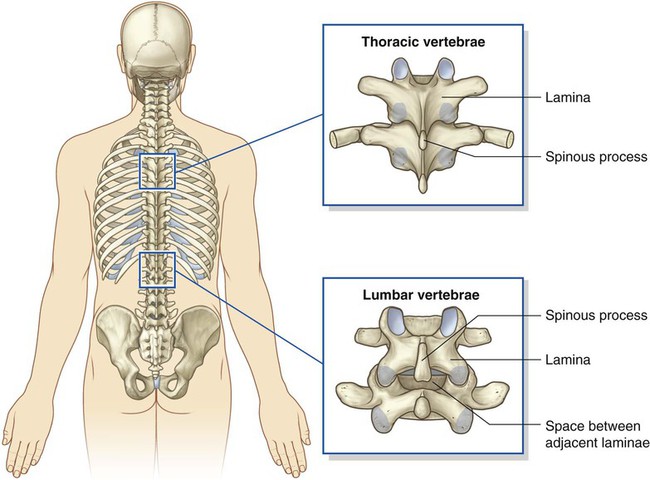

The 12 thoracic vertebrae are characterized by their articulated ribs (Figs. 2.14 and 2.16); although all vertebrae have rib elements, these elements are small and are incorporated into the transverse processes in regions other than the thorax; but in the thorax, the ribs are separate bones and articulate via synovial joints with the vertebral bodies and transverse processes of the associated vertebrae.

The 12 thoracic vertebrae are characterized by their articulated ribs (Figs. 2.14 and 2.16); although all vertebrae have rib elements, these elements are small and are incorporated into the transverse processes in regions other than the thorax; but in the thorax, the ribs are separate bones and articulate via synovial joints with the vertebral bodies and transverse processes of the associated vertebrae.

Inferior to the thoracic vertebrae are five lumbar vertebrae, which form the skeletal support for the posterior abdominal wall and are characterized by their large size (Figs. 2.14 and 2.17).

Inferior to the thoracic vertebrae are five lumbar vertebrae, which form the skeletal support for the posterior abdominal wall and are characterized by their large size (Figs. 2.14 and 2.17).

Next are five sacral vertebrae fused into one single bone called the sacrum, which articulates on each side with a pelvic bone and is a component of the pelvic wall.

Next are five sacral vertebrae fused into one single bone called the sacrum, which articulates on each side with a pelvic bone and is a component of the pelvic wall.

Inferior to the sacrum is a variable number, usually four, of coccygeal vertebrae, which fuse into a single small triangular bone called the coccyx.

Inferior to the sacrum is a variable number, usually four, of coccygeal vertebrae, which fuse into a single small triangular bone called the coccyx.

Typical vertebra

The two pedicles are bony pillars that attach the vertebral arch to the vertebral body.

The two pedicles are bony pillars that attach the vertebral arch to the vertebral body.

The two laminae are flat sheets of bone that extend from each pedicle to meet in the midline and form the roof of the vertebral arch.

The two laminae are flat sheets of bone that extend from each pedicle to meet in the midline and form the roof of the vertebral arch.

Cervical vertebrae

B. Atlas and axis. C. Typical thoracic vertebra. D. Typical lumbar vertebra.

E. Sacrum. F. Coccyx.

The vertebral body is short in height and square shaped when viewed from above and has a concave superior surface and a convex inferior surface.

The vertebral body is short in height and square shaped when viewed from above and has a concave superior surface and a convex inferior surface.

Each transverse process is trough shaped and perforated by a round foramen transversarium.

Each transverse process is trough shaped and perforated by a round foramen transversarium.

The spinous process is short and bifid.

The spinous process is short and bifid.

Atlas and axis

Thoracic vertebrae

Lumbar vertebrae

Sacrum

Intervertebral foramina

posteriorly by the zygapophysial joint between the articular processes of the two vertebrae, and

posteriorly by the zygapophysial joint between the articular processes of the two vertebrae, and

anteriorly by the intervertebral disc and adjacent vertebral bodies.

anteriorly by the intervertebral disc and adjacent vertebral bodies.

Posterior spaces between vertebral arches

Back