62

CHAPTER OUTLINE

■ AVERSION THERAPY AS PART OF A MULTIMODALITY TREATMENT PROGRAM

■ EFFECT OF AVERSION ON URGES TO DRINK ALCOHOL

■ EFFECT OF AVERSION ON COCAINE CRAVING

■ DETERMINANTS OF RELAPSE AFTER AVERSION TREATMENT

■ AVERSION THERAPY AS PART OF ESTABLISHED CARE FOR ADDICTIVE DISEASE

■ CRITICISMS OF AVERSION THERAPY

AVERSION THERAPY AS PART OF A MULTIMODALITY TREATMENT PROGRAM

Aversion therapy, or counterconditioning, is a powerful tool in the treatment of alcohol and other drug addiction. Its goal is to reduce or eliminate the “hedonic memory” or craving for a drug and to simultaneously develop a distaste and avoidance response to the substance. Unlike punishments (jail, firings, fines, divorce, hangovers, cirrhosis, and the like), which often are delayed in time from the use episode, aversion therapy relies on the immediate association of the sight, smell, taste, and act of using the substance with an unpleasant or “aversive” experience.

This treatment is not designed to appeal to the logical part of the individual’s brain, which often is all too aware of the negative consequences of alcohol and other drug use, but to the part of the brain where emotional attachments are made or broken through experienced associations of pleasure or discomfort. Aversion therapy provides a means of achieving control over injurious behavior for a period of time, during which alternative and more rewarding modes of response can be established and strengthened (1). It is first reported to be used in America by Benjamin Rush, a physician, in 1789 (2).

People need care—behavior needs modification. It is important not to confuse aversion with punishment. In punishment, it is the individual who receives the negative consequence, whereas in aversion therapy the negative consequence is only paired with the act of using a drug. This has a very important benefit to self-esteem. While the patient is engaging in positive recovery activities, he or she is receiving immediate positive support for a new way of behaving and thinking. It is only when the patient is engaging in an old behavior—alcohol or drug use—that he or she experiences immediate and consistent discomfort. Hence, self-esteem is rebuilt by separating the drug from the self (3).

In nonaddicted populations, hangovers have been cited as a significant reason to cut down or stop drinking (4). However, the hangover is delayed in time from the actual use of alcohol; thus, for the alcoholic, who drinks for the immediate euphorogenic effects of alcohol, a hangover often is ineffective in producing aversion because it is delayed in time from use of the substance whose immediate effect was experienced as pleasant or euphoric. Moreover, the discomfort of a hangover, though logically understood to be the result of drinking, is blamed on “drinking too much” (weakness) rather than drinking at all (disease). Even worse, alcohol may be used to cure the withdrawal (“hair of the dog”), which ensures that emotionally the patient perceives the alcohol as a solution, not a problem.

Contrary to popular belief, disulfiram (Antabuse) is not an aversion treatment. In aversion therapy for alcohol addiction, alcohol is not absorbed into the system (3). With disulfiram, alcohol must be absorbed and metabolism begun for it to produce its toxic effect (5). Aversion relies on safe but uncomfortable experiences that can be repeated, whereas disulfiram reactions can be life threatening, even in healthy persons. For this reason, patients today are not given alcohol at the same time that they are prescribed disulfiram. As a result, they have not actually experienced a disulfiram reaction. Thus, disulfiram does not change the way the addict feels about alcohol. He or she may fear the consequence of drinking, just as he or she fears being arrested for drinking and driving; nevertheless, he or she still retains the euphoric recall of past episodes of drinking alcohol and hence the craving for the alcohol itself. Aversion works to eliminate or reduce euphoric recall by recording new negative experiences with the drug (6).

In fact, spontaneous aversions are common, because the capacity to develop aversions is a biologic defense mechanism. DeSilva and Rachman (7) published a study of 125 students and hospital employees, 105 (84%) of whom had a history of natural aversions. There were an average of 3.5 aversions per person (females more than males), and 70.1% had been present since childhood.

PRINCIPLES OF CONDITIONING

Ivan Pavlov noted that the repetitive pairing of a bell with food soon led to a “conditioned response” in dogs, who salivated at the sound of the bell alone, even with no food present. This type of pairing or training is called classical conditioning.

B.F. Skinner expounded on the observation that the nervous system is so constructed that organisms will reduce or avoid behavior that is consistently paired with negative consequences and will increase behavior that is rewarded. This type of learning is called operant conditioning. Both types of learning can be shown to occur in addiction (8). Aversion therapy uses these principles in reversing the drug-rewarded learning and conditioned reflex to seek drugs.

The development of an aversion can be very specific. Inadequate treatment can occur when aversion is developed only to one type of alcoholic beverage (9,10). In professional alcohol addiction treatment, for example, 50% of trials may be with the addict’s favorite brand or type of liquor, but the other trials include a range of alcoholic beverages (3,11).

Repetition is an essential part of training and conditioning (12). Adequate trials are needed to develop an aversion (11) and to maintain and reinforce it to prevent extinction (13,14).

Addicts already have been conditioned by the drug prior to entry into treatment. Studies have shown that alcoholics increase the number of swallows and amount of salivation in response to the sight of alcohol, as compared to nonalcoholics (15). Studies of smokers seeking to quit show that those who are least likely to quit have a much larger conditioned drop in pulse (presumably to compensate for the increase in pulse rate caused by smoking) when presented with a cigarette (16). Cocaine-dependent addicts experience progressively steeper drops in skin temperature and increased galvanic skin response (a sign of arousal) when viewing progressively more intense and explicit pictures of cocaine use. These responses can be shown to decay in strength as time away from the drug increases.

The presence of these phenomena suggests that one of the consequences of addiction is that the body becomes conditioned to drink or use drugs in the presence of certain stimuli. This may contribute to the sensation of physical craving experienced by addicts. The availability of drugs such as heroin or cocaine in the environment also influences craving (17–19).

USES OF AVERSION THERAPY

Aversion Therapy in Smoking Cessation

It is estimated that more than 80% of smokers wish to quit but feel compelled to continue smoking because of the difficulty of stopping; indeed, the annual spontaneous recovery rate for smokers is less than 5% (20). Sachs (20,21) reviewed modern smoking cessation treatments and concluded that programs that use rapid smoking aversion or satiation had superior outcomes. Rapid smoking or satiation involves smoking cigarettes with inhalations every 6 seconds. Sessions last an average of 15 minutes, and the subject smokes an average of five cigarettes (22). The treatment sessions are usually daily for 5 days with a tapering frequency of booster treatments after that. When compared to the physical effects of normally paced smoking, clients undergoing rapid smoking experience increased burning in the lungs, palpitations, facial flush, headache, and feeling faint or weak (23). Hall et al. (24) and Lando (25) reported in separate studies that the best results were reported by programs in which aversion was combined with several other modalities, including relapse prevention, relaxation training, written exercises, contract management, booster sessions of aversion, and group support. Hall et al. (26) found that skills training (cue-produced relaxation training, commitment-enhanced training, and relapse prevention training) had more of an effect than the type of aversive smoking on outcome. Conversely, in a study of 18 patients with cardiopulmonary disease, Hall et al. (22) reported that those in a waiting list control group had no abstinence as compared with those treated with satiation aversion, 50% of whom achieved 2-year abstinence. Their study of 18 patients with cardiopulmonary disease who underwent satiation treatment also found no myocardial ischemia or significant arrhythmia in this group. Five patients with ischemic changes on the treadmill did not experience the changes during the satiation treatment.

Much of the research on aversion therapy for smoking cessation has focused on improved outcomes with aversive smoking (puffing or inhaling smoke from the cigarette in a rapid manner to induce nicotine toxicity, often including nausea) (27). Though nicotine is taken into the system during this treatment, the aversion developed to smoking is adequate to prevent relapse despite the transient presence of nicotine in the bloodstream during treatment. A Cochrane Review of 25 trials of aversions therapy for smoking reported that “the existing studies provide insufficient evidence to determine the efficacy of rapid smoking, or whether there is a dose response to aversive stimulation. Milder versions of aversive smoking seem to lack specific efficacy. Rapid smoking is an unproven method with sufficient indications of promise to warrant evaluation using modern rigorous methodology” (28). Faradic aversion (mild electrical stimulus applied to the forearm) has been used commercially for smoking cessation since 1972 (29). With faradic aversion, the smoke is not inhaled but merely puffed. Inhaling during faradic aversion may lead to early relapse because of maintenance of the nicotine dependence (30).

One advantage of this form of treatment is that less medically sophisticated staff can supervise the administration of the treatment. In both forms of treatment, patients personally administer the aversive agent (rapid smoking or electrical stimulus) to themselves, while the therapist serves as a coach. In the case of faradic aversion, each time a patient brings a cigarette toward his or her lips, a mild electrical stimulus is administered automatically by a 9-V battery. The stimulus is activated by a string attached to the smoker’s wrist. The therapist also instructs the patient in relapse prevention methods and behavior and dietary changes that help maintain abstinence and achieve comfort during the initial period after smoking cessation. Smith (29) contacted 59% of 556 patients treated with this method in a commercial program and found that 52% had achieved continuous abstinence at 1 year.

Aversion Therapy for Alcohol Addiction

The spontaneous recovery rate for alcoholism is influenced by a variety of factors, including severity of problems, age, and the presence of a co-occurring psychiatric disorder (31). Nevertheless, the annual spontaneous recovery rate estimated by Vaillant in his study of the natural history of alcoholism was 2% to 3% (32). In 1949, Voegtlin and Broz (33) published a 10.5-year follow-up of 3,125 patients treated with aversion therapy. One-year abstinence rates of 70% were reported using chemical aversion therapy with minimal counseling.

There are three well-conducted controlled trials of aversion therapy for alcohol dependence. Boland et al. (34) evaluated the 6-month abstinence rates for 50 lower socioeconomic alcoholics, using lithium as a chemical aversive agent. Twenty-five patients given emetic aversion with lithium had 36% total abstinence, as compared to 12% for the 25 patients given control treatment (p < 0.05). Cannon et al. (35) divided 20 Veterans Administration patients into three groups and found that there was little difference in outcome between seven patients given chemical aversion and those given control treatment (both groups, however, had extremely high abstinence rates: 170 to 180 days for the chemical aversion group vs. 158 to 180 days for the control group). Both did better than seven patients receiving faradic aversion. However, the groups were small, there may have been some ceiling effect, and the subjects had to drink some alcohol during the actual testing sessions, which could counteract any aversion being developed.

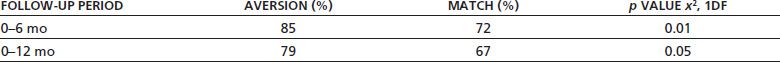

In the private sector, Smith et al. (14) compared 249 inpatients receiving aversion therapy as part of a multimo-dality treatment program with 249 inpatients from a large treatment registry of more than 9,000 patients receiving multimodality treatment but without aversion therapy. All were matched on 17 baseline characteristics. Of the patients receiving aversion therapy, 84.7% had total abstinence from alcohol at 6 months, compared with 72.2% in the control group (p < 0.01); at 1 year, 79% of those treated with aversion had maintained abstinence, versus 67% of those without such treatment (p < 0.05; Table 62-1). The group showing the greatest benefit from aversion therapy was the daily drinkers (84% vs. 67%; p < 0.001).

TABLE 62-1 PERCENT ABSTINENCE FROM ALCOHOL DURING SPECIFIED FOLLOW-UP PERIODS

From Smith JW, Frawley PJ, Polissar L. Six- and twelve-month abstinence rates in inpatient alcoholics treated with either faradic aversion or chemical aversion compared with matched inpatients from a treatment registry. J Addict Dis 1997;16(1):5–24.

Though the majority of patients in the study were treated with chemical aversion therapy, a subsample of 28 patients received faradic aversion instead. The decision to prescribe faradic aversion instead of chemical aversion within clinical practice usually is based on the patient’s medical condition. If the patient has a medical contraindication to chemical aversion therapy, then faradic is prescribed. Jackson and Smith (36) reported that patients selected in this way had nearly identical abstinence rates. In a more recent study, the same results were found (37). Blake (38) found that alcoholics treated with relaxation training, motivational arousal, and faradic aversive conditioning had a 6-month follow-up of 100% and an abstinence rate of 54% and a 12-month follow-up rate of 100% and an abstinence rate of 52%.

Neueberger et al. (39) found 1-year abstinence rates of 50% to 56% in patients treated with chemical aversion therapy. As a replication study, Wiens and Menustik (40) found total abstinence rates of 63% in patients treated with chemical aversion therapy. A meta-analysis by Thurber (41) of six studies on chemical aversion therapy found support for chemical aversion that uses nausea as the unconditioned stimulus (emetine and lithium). These had a significant effect size but not paralysis-inducing drugs (succinylcho-line chloride or suxamethonium). He found that aversion accounted for 9% of the variance in outcomes. Caddy and Block (42) review the use of vertigo to produce a nausea aversion, but no outcome study using this method in clinical practice is available.

Garcia and Koelling (43) compared stimulus conditioning in rats, comparing lithium and radiation that produced unconditioned nausea in rats to electric shock to the paw. Rats conditioned with lithium and radiation developed conditioned nausea to a gustatory stimulus but not to an auditory stimulus, whereas rats conditioned with shock to the paw developed conditioned avoidance to an auditory/visual stimulus but not to a gustatory stimulus. These preclinical findings suggest that humans and other organisms may be biologically predisposed to form long-lasting conditioned aversions to consumables such as alcohol and foodstuffs whose consumption is followed by nausea and vomiting.

Nausea Aversion

Smith (3) has report of nausea as an aversion technique. Before a typical treatment session, the patient is kept NPO except for clear liquids for 6 hours, which reduces the risk of solid stomach contents being aspirated. After informed consent about the procedure is obtained, the patient is escorted to a small treatment room that has bookcases filled with bottles of various alcoholic beverages and wall hangings of alcohol-related advertising. This provides sufficient visual cues related to drinking alcohol. After the patient sits in a comfortable chair with an attached large emesis basin, he or she receives a pilocarpine and ephedrine injection to elicit arousal of the autonomic nervous system. The patient is given an oral dose of emetine. Prior to the expected onset of emesis (5 to 8 minutes), the patient drinks two 10-oz glasses of lightly salted warm water (to counteract electrolyte loss), which creates a bolus of easily vomited fluid. The clinician doing the procedure pours a drink of the patient’s preferred alcoholic beverage, diluting it 1:1 with warm water, and presents it to the patient just prior to the expected onset of nausea. The patient smells the drink, takes a small mouthful to swish around, and then spits it out into the basin. The “sniff, swish, and spit” procedure provides a differentiated visual, olfactory, and gustatory experience that will be linked to the patient’s preferred beverage before the aversive stimulus of nausea begins. After nausea and vomiting begin, the patient can then “sniff, swish, and swallow” the preferred beverage mixture, but it stays down for only a short time, with little absorption, before it is vomited up. This first phase of intensive conditioning, which lasts 20 to 30 minutes, is followed by a second, longer phase back in the hospital room, where the preferred alcohol-containing beverage, which contains an oral dose of emetine and tartar emetic, is drunk after another 30 minutes. This precipitates residual nausea for up to 3 hours duration. Five treatments are given on an every other day basis to a typical patient over 10 days.

Howard (44) has provided a detailed review of the production of nausea and vomiting as treatment progresses. He showed that both nurses and patients reported on a 0 to 3 scale progression from 2.22 and 2.30, respectively, after the first treatment to 2.99 and 3.00, respectively, at the end of the fifth treatment. By the third treatment, more than 95% of patients and nurses reported the production of nausea and vomiting.

Faradic Aversion Therapy for Alcohol

For a faradic session, Smith (3) suggested that a pair of electrodes is placed 2 inches apart on the forearm of the patient’s dominant hand. An electrostimulus machine provides 1 to 20 mA of direct current through the electrodes, and the therapist begins test stimuli in increasing amplitude to determine the stimulus that the patient will experience as aversive. This must be done on each session as there is wide variation by day within and between patients that requires individual thresholds set for each patient on each day.

The intervention pairs the visual, olfactory, and gustatory stimuli of alcoholic beverages with the predetermined amplitude of electrostimulation that the patient will find aversive. The clinician directs the patient to pour some of a bottled alcoholic beverage into a glass and to taste it but not to swallow it. During this forced-choice phase, from reaching for the bottle to tasting the drink, the onset of the aversive stimulus occurs at random intervals, with varying numbers (from 1 up to 8) of aversive stimuli among trails. A free-choice phase of 10 supplemental trials provides negative reinforcement, such that if the patient selects a nonalcoholic choice such as fruit juice, the aversive stimulus is removed. The clinician monitors the patient’s compliance with the directive that he or she must not swallow any alcohol at any time during the treatment session.

Sessions last 20 to 45 minutes, depending on the individual patient. After the aversion conditioning session in the treatment room, the patient returns to his or her room, listens to a relaxation tape, makes a list of positive changes with sobriety, and contrasts them with the negative consequences of continued use.

Covert Sensitization

Elkins (45,46) has published on the use of covert sensitization to demonstrate that conditioned nausea responses can be trained in alcoholic patients through the use of imagination and verbal suggestion without the use of an emetic drug. In covert sensitization, patients are helped to imagine personally relevant drinking scenes that emphasize the motivational, sensory, and behavioral precursors and concomitants of alcohol ingestion. The drinking scenes then are paired repeatedly with verbally induced nausea. Most cooperative participants can learn to experience genuine and intense nausea reactions by focusing on the therapist’s noxious verbal suggestions; these suggestions prompt recipients to remember and recreate prior feelings and thoughts that have been prominent in their former nausea experiences. Such verbally induced nausea is designated as demand nausea. Repeated presentations of the drinking scenes (i.e., conditioned stimulus or CS) followed by episodes of verbally induced demand nausea (i.e., unconditioned stimulus or US) can, over extended conditioning trials, produce conditioned aversions to alcohol in a majority of participants. Elkins (45) described behavioral and psy-chophysical indices that can be used to define an individual subject’s transition from demand nausea to conditioned nausea, the goal of treatment. Conditioned nausea is nausea as an automatic consequence of the patient’s focusing on a drinking scene without any attempted therapist or self-induction of nausea.

Fifty-two patients were entered. Thirty-three were able to develop verbally induced nausea after imagined drinking scenes. It took an average of four CS–US pairings over an average of 1.8 sessions to develop this demand nausea. Of these patients, 23 were able to develop conditioned nausea to either the desire for alcohol or other alcohol-related physical stimuli. It took an average of 13.43 scenes over 4.83 sessions for them to develop conditioned aversion. Of note, the 10 patients who did not develop conditioned nausea had the same number of training sessions compared to those who did (11.79 vs. 11.64) but had more scenes (48.48 vs. 37.82).

Those who developed conditioned nausea had an average of 13.74 months of total abstinence as compared to 4.52 months for those who failed to progress beyond the demand nausea stage or treatment (p < 0.05). Elkins suggests that some patients are resistant to developing conditioned nausea to alcohol, despite the ability to develop demand nausea to verbal prompting.

Aversion Therapy for Marijuana Dependence

The spontaneous recovery rate from marijuana dependence is not known and, like that for alcohol and nicotine, probably depends on multiple factors. Chemical aversion using emetine has been used for marijuana dependence. In clinical practice, aversion therapy for marijuana uses faradic aversion. The protocol for faradic aversion is similar to that of the treatment for alcohol, except that it uses a variety of bongs, drug paraphernalia, and visual imagery. An artificial marijuana substitute and marijuana aroma are used in treatment. A 1-year abstinence rate of 84% was reported after 5 days of treatment, combined with three weekly group sessions on self-management techniques (47).

Aversion Therapy for Cocaine-Amphetamine Dependence

The spontaneous recovery rate from cocaine or amphetamine dependence is not known. Rawson et al. (48) followed 30 patients who had requested information about stopping cocaine but had not used treatment for an 8-month period; 47% were reported at the follow-up point to be using cocaine at least monthly. No total abstinence figures are available. Frawley and Smith (49) reported the use of chemical aversion for the treatment of cocaine dependence. In this treatment, an artificial cocaine substitute called articaine was developed from tetracaine, mannitol, and quinine. Patients snorted this substance and paired it with nausea induced by emetine. Of those so treated, 56% were continuously abstinent and 78% currently abstinent (i.e., for the prior 30 days) at 6 months after treatment; at 18 months, 38% were continuously abstinent and 75% currently abstinent. For those treated for both alcohol and cocaine, 70% were continuously and currently abstinent from cocaine at 6 months, 50% were continuously abstinent, and 80% were currently abstinent at 18 months after treatment.

Frawley and Smith (50) reported a 53% 1-year continuous abstinence rate in 156 cocaine- and/or amphetamine-dependent patients treated with aversion. This was based on a 73% follow-up rate. Outcomes for chemical and faradic aversion were not significantly different. The report also compared patients with both alcohol and cocaine dependencies who were treated with aversion to alcohol only with a later group when aversion was available for cocaine also. The addition of the aversion for cocaine produced statistically significantly improved abstinence rates in this population. The increase in cocaine abstinence in the later group compared to the first (55% vs. 88%) is greater than the decrease on follow-up from the first to the second group (84% vs. 64%). Because of the lower follow-up rate in the second study, this research needs replication.

Elkins et al. (51) reported a well-designed experimental evaluation of three aversion therapy treatments for cocaine dependence. Volunteer participants from the Augusta VA Medical Center (VAMC) Substance Abuse Treatment Program (SATP) were assigned to one of three aversion therapy treatments or to one of two control groups. All accepted participants satisfied the stringent medical criteria that must be met for participation in emetic therapy, the most physically demanding treatment. The additional two experimental treatments were faradic therapy and covert sensitization therapy. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the three aversion therapy groups or to one of the two control conditions—milieu treatment or relaxation therapy. Milieu therapy was the baseline control treatment that was received by all SATP participants. Emetic and faradic therapy participants used realistic placebo cocaine products during their assigned aversion interventions. The covert sensitization subjects imagined cocaine usage in conjunction with verbal nausea induction. The placebo cocaine products included simulated “rocks” of crack cocaine, simulated snortable cocaine, and Psychem, an essence that contains oils that mimic the odor of street cocaine. Each “rock” of smokeable placebo cocaine was prepared from benzocaine, baking soda, and water. Snortable placebo cocaine consisted of 97% mannitol, 1% quinine, and 2% tet-racaine in powder form. The quinine was added to simulate the bitter aspect of cocaine, and the tetracaine was added to mimic the “nose-deadening” anesthetic properties of snorted cocaine (49). All efforts were made to provide paraphernalia for snorting and smoking the placebo cocaine that resembled each patient’s customary paraphernalia. All aversion therapy sessions were completed without any serious side effects. Posttreatment abstinence performance was rigorously tracked during a 6-month follow-up period through telephone queries of the participants and their designated collateral contacts and via in-person contacts that included urine drug screens. Patients lost during follow-up were classified as relapsed.

A major positive outcome of this study is found in the emetic therapy participants’ significantly elevated post-treatment abstinence performance. The 57.9% 6-month follow-up abstinence finding for the emetic therapy recipients significantly exceeded the 26.5% 6-month abstinence finding for the milieu control participants. These emetic therapy data are quite encouraging and are consistent with the reported 56% 6-month abstinence rate from the previously discussed clinical trial of emetic therapy for cocaine dependence (49). Covert sensitization produced a significant therapeutic benefit, but its effect did not extend beyond 3 months after treatment. The second major positive outcome is found in the emetic therapy participants’ uniquely reported total loss of cravings for cocaine by the end of treatment (discussed in more detail in section “Effect of Aversion on Cocaine Craving,” below).

Aversion Therapy for Heroin Addiction

Copemann (52) employed a unique approach to aversion therapy by pairing aversive stimuli to cognitive images of heroin use. Patients were asked to verbalize only after they had conjured up a strong mental image. A second part of the treatment asked addicts to conjure images of socially appropriate behavior, involving employment, education, or nondrug entertainment. Latency to verbalization was measured. Copemann found that, at baseline, addicts could rapidly conjure up positive thoughts about heroin use but had significant delays in conjuring up thoughts about rewarding nondrug activities. Subjects were in a halfway house for heroin addicts and received group therapy in conjunction with relaxation therapy in addition to the aversion treatment. A faradic stimulator was used. Once addicts had conjured up drug images, faradic aversion was applied. At other times, addicts were given 15 seconds to conjure images of nondrug socially appropriate behavior to prevent aversion from being applied. With this training over an average of 15 sessions (range, 5 to 25), latency for drug-related images increased, while that for socially appropriate images decreased. Thirty of 50 patients completed the treatment, and, at 24 months, 80% (24 of 30) were reported to be drug-free.

Since 2012 a new approach to aversion therapy for heroin has been developed at the Schick Shadel Hospital in Seattle, Washington, under the supervision of Ralph Elkins, PhD. This heroin treatment combines hypnotically guided covert sensitization with the program’s well-established medical (emetic) counterconditioning. Seven heroin countercondi-tioning sessions are provided within the traditional 10-day inpatient multimodal treatment format that is used for alcohol and other drug dependencies. The psychologist provides hypnotic treatments as follows. The first two treatment sessions are devoted to establishing the patient’s individualized heroin use rituals, to introducing the patient to hypnotic induction, and to teaching the hypnotized patient to reexpe-rience via imagination his/her habitual heroin procurement and use rituals. The treated patients typically have reported highly realistic imagined heroin use. Elkins concludes each imagined heroin use ritual with nausea induction suggestions. The objective of the nausea suggestions is to induce genuine nausea that stops short of actual emesis. The hypnotically induced nausea starts the formation of the coun-terconditioned heroin aversion before the patient begins his/her subsequent five counterconditioning treatments that feature emetic nausea induction. The hypnotic nausea suggestions of the initial two sessions also enhance the patient’s subsequent ability to focus on his/her imagined heroin use rituals while experiencing emetic nausea induction. The patient’s ability to focus on the imagined use rituals despite emetic nausea is important because there is, as yet, no placebo heroin product that can be smoked or injected.

The patient first views typical usage paraphernalia and his/her placebo heroin visual aids upon entering the treatment room for the first of five emetic counterconditioning sessions. The patient then uses a bipolar Likert type visual desire/aversion scale (DAS) to rate his/her heroin desire or heroin aversion intensity; the ratings range from intense desire (−5) to intense aversion (+5). The ratings are repeated at the beginning and end of each treatment session to record the patient’s acquisition of an anticraving conditioned heroin aversion. The Treatment Nurse records every DAS score report as part of the patient’s permanent medical record. Following the initial DAS rating, the Treatment Nurse administers physician-ordered oral ipecac, an emetic drug that typically induces nausea and emesis within 10 to 15 minutes. The psychologist then induces hypnosis and guides the patient through a typical heroin use ritual as nausea builds to produce emesis. The emesis episode signals the end of the first imagined use ritual. According to Dr. Elkins, nausea and not emesis is the known causal basis of aversion formation. The act of emesis relieves the nausea and provides the opportunity to begin another imagined use ritual. A second imagined heroin use ritual is initiated following a brief respite during which the patient drinks water to replace lost fluid. A treatment typically includes from four to six such rituals. The patient then reports the end-of-session DAS score and returns to his/her room with the placebo heroin and usage paraphernalia for a period of extended nausea with heroin use contemplation.

Upon discharge, patients are encouraged to return for up to three overnight recap (booster) treatments during the next 90 days at no additional charge. Each recap treatment includes one emetic counterconditioning treatment, and the patient also participates in all regularly scheduled hospital activities. The patients also are encouraged to take naltrex-one, an opiate receptor blocking drug for at least 6 months following treatment.

Elkins reported that 36 patients have completed treatments since the beginning of July of 2012 (53). These patients typically entered treatment with strong DAS-confirmed heroin cravings and left with strong aversions. Patient satisfaction has been very high as confirmed via exit ratings. Additionally, more than 60% of patients who have been out of treatment for 30 days or more have returned for at least one recap treatment. Abstinence from use of the treated substance(s) is a recap requirement, and patients must pass urine drug tests before any recap treatments are administered. The pre-recap treatment DAS scores of these returning patients have confirmed their typical maintenance of strong heroin aversions. The recap patients typically have reported a marked absence of any problematical heroin cravings. Elkins is submitting case reports of several recap patients for publication. These case reports include treatments for smoked and injected heroin as well as treatments for additional problem substances including smoked opiate pills.

Use of Reinforcement (Booster) Aversion Treatments

Smith and Frawley (54) followed up at 1 year on 437 patients of 600 patients treated with chemical and faradic aversion for alcohol, marijuana, or cocaine. One-year complete abstinence rates for alcohol for those who did not return for any reinforcements (n = 51) was 29.4%; for one booster aversion treatment (n = 93), the abstinence rate was 50.5%; the two booster aversions’ (n = 273) abstinence rate was 68.5%; and for more than two aversions (n = 10), the abstinence rate was 80%. Wiens and Menustik (40) reported that the use of reinforcement aversion treatments (or recaps) was associated with improvement in abstinence at 1 year after treatment: no recaps, 24%; 1 recap, 21%; 2 recaps, 40%; 3 recaps, 27%; 4 recaps, 64%; 5 recaps, 72%; and 6 recaps, 99%. Of note, 144 of 385 (38%) patients received the 6 recaps.

Use of Support Programs and 12-Step Meetings after Receiving Aversion Therapy

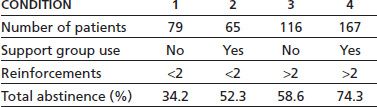

Beaubrum (55), in a follow-up study of patients, some of whom were offered group emetine aversion and AA followup, found that those who went to AA after receiving aversion had a 71% 2-year abstinence as compared to 27% who did AA alone, 18% who did aversions alone, and 23% who did neither. However, these were not random assignments. Smith and Frawley (54) found that those who used some form of support groups after aversion treatment did better than those who did not use such support. The use of any support (n = 232) versus no support (n = 195) is associated with a total abstinence rate of 68.1% versus 48.7% (p < 0.001), respectively. Smith and Frawley (54) found an additive effect of the use of reinforcement treatments and support and/or 12-step meetings after completion of a hospital aversion program. Those who did not complete at least two booster aversions and did not go to any support after treatment (n = 79) had a 1-year complete abstinence rate from all drugs of 34.2%. For those who went to support groups but did not receive at least two booster aversions (n = 65), the rate was 52.3%. For those who had at least two booster aversions but did not go to support (n = 116), the abstinence rate was 58.6%. For those who had at least two booster treatments and attended support groups (n = 167), the abstinence rate was 74.3% (Table 62-2). Though total abstinence was associated with use of support groups after treatment, for those with urges to drink, increased support use was negatively associated with abstinence. For those using AA more than once a week with urges (n = 25), the abstinence rate was 20%. For those going once a week (n = 17), the abstinence rate was 35%. For those who were going less than once a week (n = 29), the abstinence rate was 66% (p < 0.01). A similar pattern was found for patients going to Schick Shadel Hospital–sponsored support groups. For those going more than once a week (n = 9), the abstinence rate was 38%. For those going once a week (n = 30), the abstinence rate was 50%. For those going less than once a week (n = 24), the abstinence rate was 63% (p = n.s.; Table 62-3).

TABLE 62-2 ONE-YEAR TOTAL ABSTINENCE RATES: USE OF REINFORCEMENTS AND FOLLOW-UP SUPPORT

Reprinted from Smith JW, Frawley PJ. Treatment outcome of 600 chemically dependent patients treated in a multimodal inpatient program including aversion therapy and pentothal interviews. J Subst Abuse Treat 1993;10:359–369, with permission.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree