Patient Story

A 32-year-old Hispanic woman presents to your office with a chronic cough for 3 months. She states the cough is dry and started with a cold 3 months ago. She denies fever, chills, and night sweats. She has never been diagnosed with asthma or lung disease in the past. She does admit to having had persistent dry coughs that linger on after getting colds in the past. She is not sure what wheezing is but she has noticed a tight feeling in her chest at night with some whistling sound. On physical examination, her lungs are clear and she is moving air well. She is 5 feet tall and weighs 220 pounds, giving her a body mass index (BMI) of 43. Her peak expiratory flow (PEF) in the office is at 80% of predicted. Even though she is not wheezing her history and physical exam are highly suspicious for asthma. You prescribe a short-acting β2-agonist rescue inhaler with spacer and order pulmonary function tests (PFTs). You have your nurse provide asthma education (including proper use of an inhaler) and suggestions for weight loss.

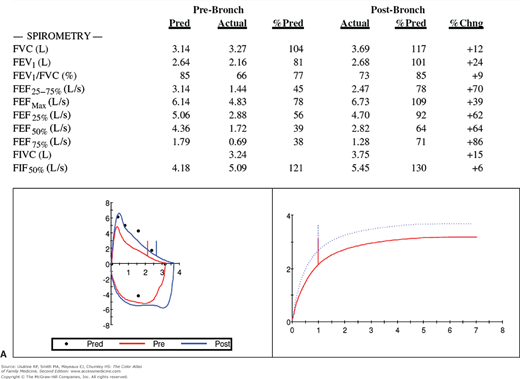

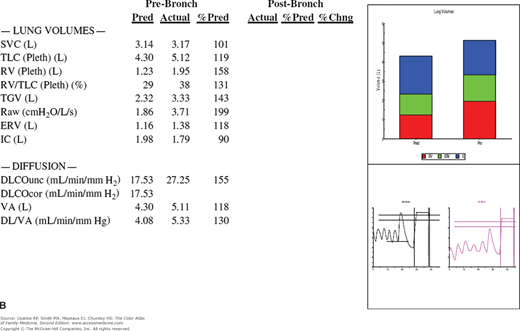

The patient returns 1 week later and the cough is much improved. You review her PFTs (Figure 55-1) and note that she has reversible bronchospasm especially in the small airways (FEF25%-75% shows a 70% improvement with inhaled albuterol). Table 55-1 lists the meaning of typical abbreviations used with PFTs. Her lung volumes (Figure 55-1B) show hyperinflation with a high residual volume and her diffusing capacity is normal. The whole picture is consistent with asthma. An asthma action plan is created and a referral to a nutritionist is offered to help the patient with her obesity.

Figure 55-1

Pulmonary function tests in a woman with suspected asthma. A. Spirometry before and after bronchodilation with flow volumes loops and graph of forced vital capacity. The FEV1 is normal, but the FEV1/FVC ratio and FEF25-75% are reduced. Following administration of bronchodilators, there is a good response especially in the small airways as represented by FEF25-75%. B. Lung volumes are all increased (especially the residual volume), indicating overinflation and air trapping. The diffusing capacity is normal. Conclusions: Minimal airway obstruction, overinflation, and a response to bronchodilators are consistent with a diagnosis of asthma. The patient has minimal obstructive airways disease of the asthmatic type. %Chng, Percent change; %Pred, percent predicted; Pre-Bronch, prebronchodilation; Pred, predicted; Post-Bronch, postbronchodilation. See Table 55-1 for additional abbreviation explanations. (Courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

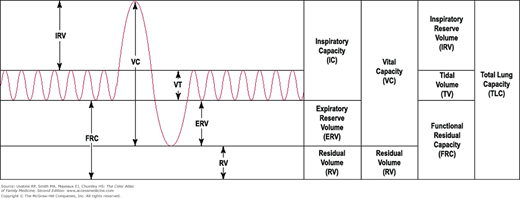

DLCO | Diffusing capacity of lung (using carbon monoxide measuring) |

DL/VA | Diffusing capacity divided by alveolar volume |

ERV (L) | Expiratory reserve volume |

FEF25% (L/s) | Forced expiratory flow rate when 25% of the FVC has been exhaled (slope of FVC curve at 25% exhaled) |

FEF25-75% (L/s) | Forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% of capacity—same as maximal mid expiratory flow (MMFR) |

FEF50% (L/s) | Forced expiratory flow rate when 50% of the FVC has been exhaled |

FEF75% (L/s) | Forced expiratory flow rate when 75% of the FVC has been exhaled |

FEFmax (L/s) | Forced expiratory flow maximum |

FEV1 (L) | Forced vital capacity at 1 second |

FEV1/FVC % | FEV1 divided by FVC |

FIF50% (L/s) | Forced inspiratory flow at 50% capacity |

FITC (L) | Forced inspiratory vital capacity |

FVC (L) | Forced vital capacity |

IC (L) | Inspiratory capacity |

Raw | Airway resistance |

RV (L) | Residual volume |

RV/TLC | Residual volume divided by total lung capacity |

SVC (L) | Slow vital capacity |

TGV (L) | Thoracic gas volume |

TLC (L) | Total lung capacity |

VA (L) | Alveolar volume |

Introduction

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory airway disorder with variable airflow obstruction and bronchial hyperresponsiveness that is at least partially reversible, spontaneously or with treatment (e.g., β2-agonist treatment). Patients with asthma have recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness, and cough (particularly at night or in the early morning).

Epidemiology

- Estimated prevalence of asthma in noninstitutionalized adults older than age 18 years in the United States (2010) is approximately 8.2% (18.7 million cases).1 There are 7 million children (9.4%) who currently have asthma. Rates of asthma are increasing; the greatest rise in rates is among black children, an almost 50% increase between 2001 and 2009.2

- The number of deaths from asthma in 2009 was 3388 (1.1/100,000 population).1

- Asthma accounts for 17 million visits per year (physician offices, emergency departments, and hospital outpatient sites).1

- Asthma was the first-listed diagnosis for 479,000 hospital discharges in 2009 with an average length of stay of 4.3 days.1

- Estimated direct costs associated with asthma in the United States grew from approximately $53 billion in 2002 to approximately $56 billion in 2007 (6% increase).2

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Although the precise cause is unknown, early exposure to airborne allergens (e.g., house-dust mite, cockroach antigens) and childhood respiratory infections (e.g., respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza) are associated with asthma development.

- In addition to environmental factors, asthma has an inherited component, although the genetics involved remain complex.3 The gene ADAM33 (A Disintegrin And Metalloproteinase) may increase risk of asthma as metalloproteinases appear to affect airway remodeling.4 A recent nested case-control study found that genetic variation in the ATPAF1 gene predisposed children of different racial backgrounds to asthma.5

- The pulmonary obstruction characterizing asthma results from combinations of mucosal swelling, mucous production, constriction of bronchiolar smooth muscles and neutrophils (the latter, particularly important in smokers or those with occupational asthma).4 The smaller airways of children make them particularly susceptible. Over time, airway smooth muscle hypertrophy and hyperplasia, remodeling (thickening of the subbasement membrane, subepithelial fibrosis, and vascular proliferation and dilation), along with mucous plugging complicate the disease.4

- Allergen-induced acute bronchospasm involves immunoglobulin-E (IgE)-dependent release of mast cell mediators.4

Risk Factors

Based on a cohort study, early life (first 5 years) risk factors for diagnosed asthma at age 10 years includes:6

- Family history of asthma (maternal [odds ratio (OR), 2.26; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.24 to 3.73]; paternal [OR, 2.30; 95% CI, 1.17 to 4.52]; sibling [OR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.16 to 3.43]).

- Recurrent chest infections at 1 year of age (OR, 2.67; 95% CI, 1.12 to 6.40) and 2 years of age (OR, 4.11; 95% CI, 2.06 to 8.18).

- Atopy at 4 years of age (OR, 7.22; 95% CI, 4.13 to 12.62).

- Parental smoking at 1 year of age (OR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.15 to 3.45).

- Male gender (OR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.01 to 2.95).

- Recent use of acetaminophen has also been associated with asthma symptoms in adolescents (OR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.33 to 1.53 and OR, 2.51; 95% CI, 2.33 to 2.70 for at least once a year and at least once a month use vs. no use, respectively).7 One possible mechanism is through acetaminophen reducing the immune response and prolonging rhinovirus infection.8

- Modifiable risk factors include obesity (OR 3.3 for adult-onset asthma) and tobacco smoking; the latter also increases the risk of occupational asthma.4 In one study, consumption of salty snacks (OR 4.8; 95% CI, 1.50 to 15.8) was strongly associated with the presence of asthma symptoms, especially in children with television/video-game viewing of more than 2 hours per day.9

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of asthma is made on clinical suspicion (presence of symptoms of recurrent and partially reversible airflow obstruction and airway hyperresponsiveness) and confirmed with spirometry.3 Alternative diagnoses should be excluded.

Asthma’s most common symptoms are recurrent wheezing, difficulty breathing, chest tightness, and cough. An absence of wheezing or normal physical exam does not exclude asthma.3 In fact, up to 25% of patients with asthma have normal physical exams even though abnormalities are seen on pulmonary function testing.4 As part of the diagnosis of asthma, ask about the following:3

- Pattern of symptoms and precipitating factors. Symptoms often occur or worsen at night and during exercise, viral infection, exposure to inhalant allergens or irritants (e.g., tobacco smoke, wood smoke, airborne chemicals), changes in weather, strong emotional expression (laughing hard or crying), menstrual cycle, and stress.3

- Family history of asthma, allergy, or atopy in close relatives.

- Social history (e.g., daycare, workplace, social support).

- History of exacerbations (e.g., frequency, duration, treatment) and impact on patient and family.

Findings on physical exam may include:3

- Upper respiratory tract—Increased nasal secretion, mucosal swelling, and/or nasal polyp.

- Lungs—Decreased intensity of breath sounds is the most common (33% to 65% of patients).4 Additional findings may include wheezing, prolonged phase of forced exhalation, use of accessory respiratory muscles, appearance of hunched shoulders, and chest deformity. During a severe exacerbation of asthma, minimal airflow may result in no audible wheezing.

- Skin—Atopic dermatitis and/or eczema (Chapters 145, Atopic Dermatitis, 147, Hand Eczema, and 148, Nummular Eczema). There is a strong association between asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema (Figure 55-2), although the “atopic or allergic triad,” with the coexistence of all three conditions at one time (Figure 55-3), is not very common. Children with asthma are also more likely to develop pityriasis alba, a chronic skin disorder characterized by patches of lighter skin mainly on the face (Figure 55-4). In a U.S. study of children with physician-confirmed atopic dermatitis (N = 2270), 38% reported symptoms of asthma and allergic rhinitis on a survey10; similarly in a population study in Taiwan using the National Insurance register, of the 66,446 individuals diagnosed with atopic dermatitis, approximately 50% had a concomitant diagnosis of allergic rhinitis and/or asthma.11 Data support a sequence of atopic manifestations beginning typically with atopic dermatitis in infancy followed by allergic rhinitis and/or asthma in later stages.12

Findings in patients with status asthmaticus (prolonged/severe asthma attack that is not responsive to standard treatment) may include:4

- Tachycardia (heart rate >120 beats/min) and tachypnea (respiratory rate >30 breaths/min).

- Use of accessory respiratory muscles.

- Pulsus paradoxus (inspiratory decrease in systolic blood pressure >10 mm Hg).

- Mental status changes (as a consequence of hypoxia and hypercapnia).

- Paradoxical abdominal and diaphragmatic movement on inspiration.

Spirometry is recommended by National Asthma Education Program (NAEP) for all patients older than 4 years of age to determine airway obstruction that is at least partially reversible (Figures 55-1, 55-5, and 55-6).3 SOR B

- Assess severity—Severity is defined as the intrinsic intensity of the disease process.3 The NAEP divides severity into four groups: intermittent, persistent-mild, persistent-moderate, and persistent-severe (Table 55-2).

- Initially, severity can be assessed in the office, urgent, or emergency care setting with predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) or PEF; a value of less than 40% indicates a severe exacerbation. A value of equal to or greater than 70% predicted FEV1 or PEF is a goal for discharge from the emergency care setting.

- Once asthma control is achieved, severity can be assessed by the step of care required for control (i.e., amount of medication) (Table 55-2).

| Intermittent | Mild Persistent | Moderate Persistent | Severe Persistent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | ≤2 times/week | More than 2 days per week | Daily | Throughout the day |

| Nighttime Awakenings | ≤2 times/month | 3-4 × per month | Greater than once per week but not nightly | Nightly |

| Inhaler Use for symptom control (rescue use) | ≤2 days/week | > 2 days per week, but not daily | Daily | Several times per day |

| Interference with Normal Activity | None | Minor limitation | Some limitation | Extremely limited |

| Lung Function | FEV1 >80% predicted and normal between exacerbations | FEV1 >80% predicted | FEV1 >60%-80% predicted | FEV1 less than 60% predicted |

Additional tests that may be useful include:3

- Pulmonary function testing if a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), restrictive lung disease, or vocal cord dysfunction is considered.

- Bronchoprovocation (using methacholine, histamine, cold air, or exercise challenge) if spirometry is normal or near-normal and asthma is still suspected; a negative test is helpful in ruling out asthma.

- Pulse oximetry or arterial blood gas if hypoxia is suspected (e.g., cyanosis, rapid respiratory rate).

- In the emergency room setting, B-type natriuretic peptide can help distinguish between heart failure and pulmonary disease.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree